“He was in the fire, and we were lookin’ into it,” Brewers backstop Ted Simmons said to New Yorker writer Roger Angell in the spring of 1983. Simmons was speaking about Steve Lake, a fellow Milwaukee catcher; while Lake had been behind the plate in an Arizona exhibition game, Simmons and two younger catchers had been on the bench, trying to think along with Lake and determine the perfect pitch to call. In the dugout, they debated the merits of fastballs vs. breaking balls on 2-2 counts, but they didn’t disturb Lake, who had work to do and no time to talk. He was in the fire and beyond being helped.

That sentence from Simmons, which Angell lifted for the title of a 1984 essay, is apt because we watch catchers the way we watch fires: mesmerized by their movements, but lulled into bleariness and barely aware of the atomic interactions producing the surface effects that we see. Catching is complicated, a combination of technical craft and cult of personality; it’s receiving, blocking, throwing, defensive positioning, and pitch-calling, all folded into the same physically punishing pursuit. The other seven spots in the infield and outfield are positions. Catching is an imposition. And almost cruelly, catchers also have to hit.

Elsewhere in his essay, Angell noted that the catcher briefly becomes the center of attention on plays at the plate but lamented “the anonymity we have carelessly given to our receiver in the other, and far more lengthy, interludes of the game.” In recent years, catchers have, for their own safety, surrendered the star-making, occasionally career-breaking practice of blocking the baseline, but on balance, they’ve gained greater renown. The advent of pitch-tracking technology has confirmed the existence of the position’s long-suspected but theretofore-unproven powers, revealing the vast value that skilled strike-stealers can accrue across thousands of toss-up pitches and spawning fawning features about framing and GIF-filled exegeses about catchers who’ve abruptly ascended or descended the new-look leaderboards.

Although there’s less truth today to Angell’s assertions that “our awareness of the catcher is glancing and distracted” and “the catcher is invisible,” catchers’ work at the plate hasn’t received the same reappraisal as their labor behind it. Catcher defense, with its whiff of fading inefficiencies, is still sexy. Catcher offense is comparatively prosaic: Over the past three seasons, catchers have, on balance, been baseball’s weakest-hitting non-pitchers. No stat can salvage their pedestrian triple-slash stats.

Yet even when catchers remove their helmets and armor and adopt their everyman alter egos on offense, they can’t quite shake their unique nature. To a greater degree than players at other positions, catchers’ work in the field follows them to the plate, bringing burdens and blessings. With help from a few new-age numbers and a couple of catchers who’ve been in the fire, let’s examine three theories about catchers’ performance at the plate: that umpires extend them the courtesy of more favorable strike zones; that they have an advantage against pitchers they’ve previously caught; and that they have a harder time hitting when paired with pitchers who rely on the catcher’s nightmare, the knuckleball.

Home-Plate Advantage

“Does the man back there know what’s going on?” Simmons said to Angell in the same spring exchange. “If he does, he can throw bad and he can run bad and block bad, but he’s still the single most important player on the field.”

Simmons could have been describing current Braves backstop Tyler Flowers, who hadn’t yet been born. Like most catchers, Flowers’s speed doesn’t distinguish him, and he’s been below average in blocking and throwing in each of the past three seasons. Nonetheless, he’s provided an extraordinary return on his modest salaries, totaling 11.4 Wins Above Replacement Player, by Baseball Prospectus’s math, in only 294 games from 2015-17. Last year, Flowers was the most prominent player at what BP’s stats say was the most productive position in baseball: not center field for the Angels, second base for the Astros, or right field for the Marlins, but backstop for the Braves, where Flowers, Kurt Suzuki, and a small-sample pair of real replacement players combined for a total of 9.3 WARP.

Flowers’s WARP outstrips his WAR because BP’s value metric, unlike those of other sites, considers receiving. Although Flowers played only 99 games last season, his framing earned 193 extra strikes for his staff, which easily led the majors. But Flowers, like other catchers, may also influence strike calls on offense.

In the fourth inning of a Braves-Cardinals contest last August, Flowers faced St. Louis starter Michael Wacha with one out and two on, following back-to-back singles. Flowers took the first pitch, a changeup over the inside part of the plate that BP’s called-strike probabilities—which account for location, count, pitch type, and pitcher and batter handedness—estimate had an 80.4 percent chance of being called a strike. Home-plate umpire Ted Barrett called it a ball.

Staked to a 1-0 advantage, Flowers went on to walk, which extended a rally that led to the first two Atlanta runs in a 6-3 Braves victory. In all likelihood, it was one of thousands of probable strikes that become balls for no better reason than a butterfly flapping its wings, or an umpire’s eyes watering, or a pitch not hitting its target. But maybe, just maybe, it was something more.

“The strike zone is whatever that day’s umpire says it is,” Ted Williams once said. “So if a hitter is smart, he knows that particular umpire as well as he knows the opposing pitcher.” No hitter knows the umpire better than the catcher. “I’m very aware of the umpire’s strike zone from a catching perspective, and I definitely apply it to my setups and what pitches I’m going to emphasize,” Flowers, who receives Statcast-powered umpire reports from the front office before every game, says by phone.

I think the psychological edge in the pitcher-catcher battle is the story the pitcher tells in their mind: ‘He knows what I’m going to throw, what it looks like, and what I like to do.John Baker, former MLB catcher

In theory, a catcher could apply that preparation at the plate, too, modulating his decisions about whether to take or swing based on both the umpire’s overall tendencies and the way he’s calling pitches in a given game. “I’d like to tell you I’m that good of a hitter to take that into account, but I’m not,” a laughing Flowers says. Maybe that’s true, or maybe he’s being modest. Or maybe offensive strike-stealing is a subconscious skill. One way or another, there’s solid evidence that catchers do exert a slight zone-shrinking effect at the plate.

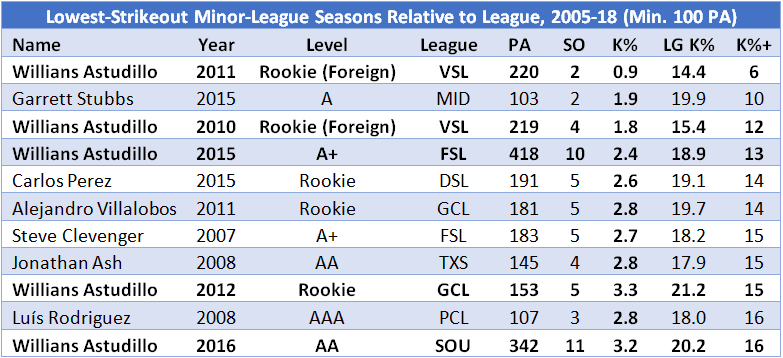

The same stat BP uses to measure catchers’ sway over the strike zone on defense—Called Strikes Above Average, or CSAA—can be calculated for batters, too. The table below lists the top 10 and bottom 10 batters in cumulative runs gained or lost from ball/strike calls since 2012:

There appears to be a pattern here. Even though this is a counting stat and catchers tend to miss more games than players at other positions, the left-hand column—which lists the hitters who’ve benefited from smaller strike zones—includes six hitters who’ve played regularly behind the plate, not including Josh Donaldson, who came up as a catcher. The right-hand column is completely catcher-free.

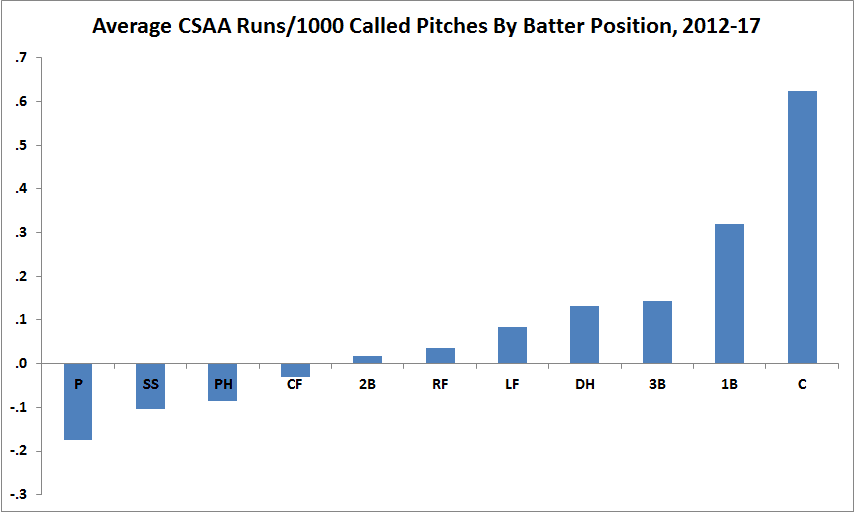

The evidence is even more compelling on a league-wide level. The graph below shows the average CSAA runs gained by batters per 1,000 called pitches, broken down by position.

For reasons that aren’t completely clear—there are no meaningful correlations between batter CSAA and age, offensive performance, swing or chase rates, or height—this distribution roughly follows the defensive spectrum, with inferior offensive positions on one side and superior positions on the other. Except, that is, for catchers, who despite their relative offensive ineptitude dwarf even first basemen in their ability to get more favorable calls.

In “In the Fire,” Angell observed that on occasion, an umpire will pick up a catcher’s cap and mask, discarded during the preceding play, and hand it to him tenderly, as if in a gesture of solidarity with the one other man on the field who knows how it feels to face the firing squad. “Here y’are, the ump’s courtly little gesture seems to say,” Angell wrote. “You poor bastard.” Maybe, then, the charitable call on a catcher is similar: an unspoken (or even unwitting) favor between the foxhole buddies of baseball, who crouch so close together that they sometimes touch. After all, while a catcher might not take a bullet for the man in blue, he will take a foul tip or a breaking ball in the dirt.

“I could see it,” Flowers says, although the calls he believed to be bad return to his mind more easily (and more maddeningly) than the ones that seemed generous. For the sake of his pitchers, Flowers tries not to anger umpires when calls go against him at the plate, but he can’t always keep quiet. “It amazes me, some people that don’t ever say anything to umpires,” he says. “I don’t know how they do it. I don’t know what other way to take it other than personal. Like, you’ve got a job to do, I’ve got a job to do. If you don’t do your job effectively, it hinders my ability to do my job.” But while his frustration sometimes seeps out, he has a kind of code. Although his framing methods may mislead umpires, he won’t gaslight them with words by exaggerating his responses to reasonable strikes in hopes of makeup calls later—except, he allows, for the 1 percent situations where distorting the truth about a pitch’s perceived location might affect a future crucial call. “I always make it a point to be honest with them, because of course I want every pitch called a strike, but when I’m hitting, I definitely don’t want every pitch called a strike, so there’s kind of that fine line that you thread,” he says.

Although CSAA reports that Flowers has profited slightly from the catcher-umpire effect, to the tune of two extra runs, he says he wouldn’t have thought so before I relayed the results. Former big league catcher John Baker, though, immediately takes the stats in stride. “I was certain catchers received the benefit of the doubt from umpires,” he says via email. Baker believes that the benefit derives less from fondness or sympathy than from a desire to avoid working in close quarters with someone who’s still steaming from an earlier injustice. “Even if the [catcher-umpire] relationship was negative, I still feel there was an effect that benefited the catcher while he was hitting,” he says. “Make a bad call on the catcher and then the umpire has to live and work in tension half the game. Not fun!”

The Familiarity Effect

On July 8, 2016, Flowers, who came up with the White Sox, returned to U.S. Cellular Field to play his old team for the first time since signing with the Braves the December before. The opposing starter was Chris Sale, whom Flowers caught for 552 innings from 2010-15—still by far the most work any one backstop has had with the sticklike lefty. On the second pitch he saw, Flowers sent a centered two-seamer from Sale to the center-field bleachers.

“It was beautiful,” Flowers says. “Just hearing all of Chicago boo as I rounded second, I couldn’t get the smile off my face.” In his second plate appearance, Flowers took a slider off his back foot for a free base; in his third, he doubled to deep right, giving him a 4.000 career OPS against Sale—the second-highest of any hitter. “My career numbers look good against him,” Flowers says, with mock confidence. “Take that to the bank.”

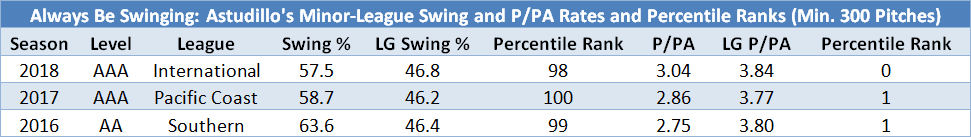

It’s conceivable that Flowers took Sale deep because he’d caught him before; perhaps his familiarity with the southpaw’s release point, pitch movement, and sequencing robbed Sale of some element of surprise. But for Flowers, it didn’t feel that way. “I’m not going to tell you I was real comfortable in there,” he confesses. Because he and Sale are good friends, he says, he wasn’t concerned about the southpaw “buzzing the tower” with a 98-mph fastball, but he was worried about being in the right frame of mind. “I feel like I have the tendency to think more when I’m facing guys that I used to catch,” he says. “Not specifically in the sense of, ‘Man, if I was catching them, I would throw a changeup right now.’ But … more than a typical at-bat for me, where I’m just focused on hunting the fastball and driving it up the middle and trusting myself to react to the off-speed, I find myself questioning what he’s really about to throw.”

Despite how he felt, history says that Flowers may have had an edge. The table below, which draws on data back to 1954, compares how catchers have performed against pitchers they’ve previously caught in the majors to their performance against all other pitchers, as measured by True Average (TAv), a park- and era-adjusted Baseball Prospectus offensive stat that consolidates all aspects of performance at the plate into one number on a batting average-like scale centered at .260.

The first two rows show the quality of the catching groups’ pitching opponents (as represented by TAv allowed), both within these splits and overall, while the third and fourth show the catchers’ offensive performance (as represented by TAv produced), also within these splits and overall. The “previously faced” sample contains more than 60,000 plate appearances, while the “not previously faced” sample contains more than a million. Matchups between former minor league batterymates aren’t included in the “previously faced” sample unless they also caught/pitched to each other in the majors.

If you skipped the preceding paragraph’s riveting stat-table breakdown, don’t worry: All you really need to know is what the bottom row reveals. In a very sizable sample, catchers have been about five TAv points better than usual when facing pitchers they’ve previously caught. That would equate to about 2.5 extra runs, or roughly a quarter of a win, over 500 plate appearances; not huge, but not nonexistent. It’s also possible that the benefit could be bigger for catchers who’ve caught an opposing pitcher frequently and/or recently.

In 82 career PA against previously caught pitchers, Flowers has hit 52 TAv points better than usual; Baker was 19 points better, in 32 career PA. Psychologically speaking, Baker might as well be Bizarro Flowers: “I … enjoyed facing guys I had caught,” he says. “I just really liked that one-on-one competition when it had a relationship to build pressure.”

Baker says that in these familiar face-offs, the pitcher can outthink himself in the same way that Flowers believes he tends to do. “I think the psychological edge in the pitcher-catcher battle is the story the pitcher tells in their mind: ‘He knows what I’m going to throw, what it looks like, and what I like to do,’” Baker says. “In reality if they just executed, and focused on execution, they’d have a much better chance, because watching what the ball does from the catcher’s perspective is much different than watching the same pitch from the perspective of the hitter.”

Flowers says that when he caught Sale, he called for more changeups than sliders, but in their first meeting as adversaries, Sale didn’t pitch him that way. Odds are Sale’s pitch selection that day was just a byproduct of an ongoing evolution, but there’s a chance that his history with Flowers—and his potential predictability—was in the back of his mind. “I definitely would’ve called some more changeups against myself,” Flowers says. “I don’t think I saw a changeup that whole day.” (Statcast confirms this.)

No Knuckle-Dragging

In the bottom of the sixth inning of a game in D.C. last July, with the score tied at 1-1 and the go-ahead run in scoring position, Flowers framed an R.A. Dickey knuckleball and froze Ryan Raburn to end a Nationals threat.

Half an inning later, though, it was Flowers’s turn to go down swinging.

That day, Dickey was dominant, but the Braves lost in extras, and Flowers finished 0-for-4 with two strikeouts. It was one of seven oh-fers Flowers took in 16 games catching Dickey last season. “It just kind of dawned on me one day that, like, ‘Man, I never seem to get hits when R.A.’s pitching,” Flowers says. As those outs on offense mounted, he remembered that his friend and fellow Chipola College alum Russell Martin, a Dickey (and knuckleballer Charlie Haeger) survivor himself, had told him about the difficulties he’d had hitting while catching Dickey in 2015, which eventually led to Martin catching Dickey less often. “That kinda made me really think about it, like, ‘I wonder if I’m having the same thing,’” Flowers says. “And then when I started looking at the numbers, it definitely seemed to be trending in that direction.”

Overall, Flowers hit .207/.303/.328 (.250 TAv) in 66 PA as a catcher in games started by Dickey, and .302/.397/.474 (.324 TAv) in 287 PA as a catcher in all other games. Each of the three other big-league backstops who caught either Dickey or Red Sox knuckleballer Steven Wright last year also hit worse in knuckleball games than non-knuckleball games, and Martin managed only a .178/.215/.329 line in 79 PA catching Dickey starts in 2015, a season in which he hit .259/.350/.494 in all other PA as a catcher. Baseball lifers have long believed in a knuckleball “hangover effect,” which may or may not hamper batters after facing a knuckleball. Maybe the knuckleball catcher has a hangover, too.

I always make it a point to be honest with them, because of course I want every pitch called a strike, but when I’m hitting, I definitely don’t want every pitch called a strike, so there’s kind of that fine line that you thread.Tyler Flowers, Atlanta Braves catcher

Catching a knuckleball is not only physically painful, but psychologically stressful. “It’s like a constant battle for that 60 feet of just watching it and focusing on it, and you try and predict the moves, but you can’t, because you don’t know what the moves are going to be,” Flowers says. Flowers isn’t sure why that would hurt his hitting, but a Braves trainer proposed a theory to the catcher. “You have X amount of fine focus you can apply per day,” Flowers says the theory went. When working with a knuckleballer, he continues, “you’re using up so much of that trying to catch every single pitch … that you just literally don’t have your ability to have that fine focus that you need [at the plate].” It’s plausible.

Dickey is no longer in Atlanta, but Flowers knows he may not have bitten the knuckleball bullet forever. Flowers says that a Braves analyst told him that he excelled at framing the knuckler, which might make another team with a knuckleballer more likely to recruit him in the future. “I do have that fear in the back of my mind that one day they’re going to make me an offer I can’t refuse, and I’m going to end up catching a damn knuckleballer again,” Flower says.

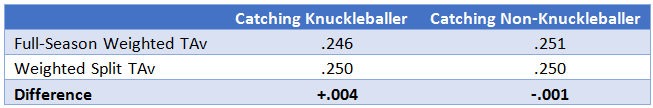

To determine whether Flowers should be afraid, I assembled a sample of 17 past and present pitchers who’ve primarily thrown a knuckleball, again extending the search back to 1954 (and in some cases excluding early-career seasons in which certain future knuckleballers hadn’t yet found their floaters). Then, using data from Baseball Prospectus, I compared their catchers’ offensive performance in their plate appearances at catcher in two separate samples: games started by those knuckleballers, and games not started by those knuckleballers.

The results are surprising: In more than 14,500 plate appearances in games started by knuckleballers, the catchers hit a few points better than their weighted full-season numbers. Not only has catching the knuckleball not held back offensive performance, it may have even augmented it. “I definitely expected you to say, ‘And it checks out throughout history!’” a rueful Flowers says. In his ’84 essay, Angell asserted that “everything about catching … is harder than it looks.” Decades later, we may have discovered an exception.

Maybe Martin’s and Flowers’s struggles should be dismissed as small samples, or maybe they had a hard time with Dickey because they were fairly new to the knuckleball. Many of the catchers who’ve caught knuckleballers were especially suited and trained for that task: Josh Thole, for instance, caught Dickey for seven seasons in New York and Toronto, and he hit significantly better in Dickey games than non-Dickey games. Knuckleball stress may subside in time.

Baker, too, is taken aback when he hears that the demands of the knuckler haven’t sabotaged the typical catcher’s performance at the plate. “After catching Steve Sparks a few times [in Triple-A] in 2005 I remember not even caring about my at-bats because the catching was so exhausting,” he says. Then again, not caring could be preferable to caring too much. “Maybe that is a better place to be as a hitter,” Baker adds.

Considering the mental and physical loads catchers carry, the concussions they sustain, and the fatigue they face, it’s only fair that they would receive some small offering in return for their troubles: a small strike-zone boost or familiarity effect baked into backstops’ stats. Similarly, it’s merciful that the knuckleball doesn’t do double damage. Catchers have it hard enough.

Aside from a sporadic Posada or Sánchez, the catcher’s contribution on offense has always seemed secondary; as Angell wrote, “hitting mattered, but perhaps not as much as the quieter parts of the job.” Although the effects we’ve found (or failed to find) are subtle, they confirm that a catcher is always a catcher, even when he removes his mask. The catcher’s box and batter’s box aren’t impassable boundaries, but permeable membranes that the position’s peculiarities can cross. Decades after “In the Fire,” catchers remain the baseball gods’ gift to the fan who seeks to sound the sport’s hidden depths. With each advance in our knowledge, we understand slightly better than before that whatever his stats, the backstop always supplies something to see. “Yeah,” Flowers says, with a catcher’s esprit de corps. “A little bit more than the first baseman.”

Thanks to Rob McQuown and Jonathan Judge of Baseball Prospectus for research assistance.