Tyler Flowers Is MLB’s Most Improved Player

How the Brave has bucked big league trends to climb from the bottom to the top of the leaderboardsOn Saturday afternoon in Oakland, the Braves and A’s played to a 1–1 tie for 4 ½ innings. In the bottom of the fifth, Braves starter R.A. Dickey — who’d at least temporarily become the oldest pitcher in baseball when the Braves designated Bartolo Colón for assignment two days prior — ran into trouble. Dickey allowed a leadoff single, a deep lineout, and a walk, then baited Jed Lowrie into a grounder that caused a force out at second, bringing up Oakland’s best power hitter, Khris Davis, with runners on first and third. After battling to a 2–2 count, Davis took a borderline knuckler. In most cases, the pitch would have been on the "ball" side of the border. But this time, Tyler Flowers was catching.

According to Pitch Info’s called-strike-probability data — which is based on the season, the count, the location (relative to the batter’s personalized zone), the pitch type, and the handedness of the pitcher and batter — a pitch like that one would be called a strike only 4.3 percent of the time. But Flowers reached out far in front of him to prevent the pitch from falling before the umpire could call it, and he subtly steered it toward the zone, pulling it up and in without drawing attention to the motion. Dickey got the call, and Davis went down looking. The game stayed tied, and the Braves went on to win by one run.

That’s one of the most recent examples of Flowers changing the game with his glove; I could have shown you dozens more from this season alone. Alternatively, I could have highlighted one of his many big days at the plate, like the two-hit performance in late June when he drove in two runs in another one-run win for Atlanta. I’m trying to avoid any puns about "blossoming," but Flowers, who was signed to be a backup on a two-year, $5.3 million deal before last season, has improved dramatically at an age (31) when many catchers are already heading downhill.

If you’re wondering how Atlanta, whom preseason projections saw as a fourth- or fifth-place team, has played well enough to take advantage of the Mets’ and Phillies’ disaster seasons and stay in second place, don’t be too quick to credit the veterans — Colón, Dickey, Jaime García, Brandon Phillips, Matt Kemp, Kurt Suzuki — the Braves brought in to make a run at respectability in their inaugural year at SunTrust Park. Look first at Flowers, who couldn’t crack the NL All-Star roster but whom one win-value metric suggests has been one of the best players in baseball. In a competitive environment that’s made it more difficult than ever for catchers’ receiving skills to stand out and for hitters to make contact, Flowers is successfully swimming upstream, getting better in both respects.

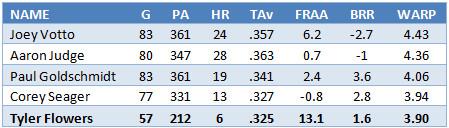

Here are the five most valuable position players in baseball through Tuesday’s games, according to Baseball Prospectus’s wins above replacement player. TAv is true average, an all-in-one offensive stat on roughly the same scale as batting average (in other words, .300 is good). FRAA is fielding runs above average; BRR is baserunning runs; and WARP — the only one of the win-value stats that incorporates catcher receiving — is a player’s complete contribution boiled down to one number.

Votto, Goldschmidt, and Seager all entered the year on the short list of the best players in baseball. Judge didn’t, but no one would dispute that he belongs. And then there’s Flowers, who entered this year with a career 88 OPS+, who’s making $3 million in his ninth big-league season (with a $4 million team option for 2018), and who’s played (and homered) a whole lot less than the sluggers at the top of the list. "Being older and being on both ends of the spectrum … maybe I have a better outlook on that than most players that are in the same position I am right now," Flowers says by phone. "A lot of them haven’t been at the bottom of the barrel like I was."

The new Flowers edges out Justin Turner, Mookie Betts, José Altuve, and Charlie Blackmon, among other 2017 standouts on the WARP leaderboard. Sure, he’s hitting .319/.412/.459, a sweet slash line for a catcher, but his hitting alone didn’t propel him to fifth on that leaderboard. This is going to take a deeper dive.

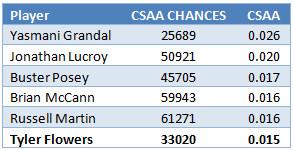

"Receiving is my passion," Flowers says, so let’s start there. He’d like to write a book about receiving someday, but not until he’s retired; he doesn’t want to divulge too many secrets while they can still help him. And they have helped him: Flowers ranks sixth in called strikes above average (a rate stat available at Baseball Prospectus) among the 32 catchers with at least 25,000 framing chances since 2009, his rookie year. (His current backup with the Braves, Kurt Suzuki, ranks sixth-worst.)

Flowers doesn’t refer to this skill as "framing," "presenting," or "strike-stealing." He thinks of it less as a means of gaining strikes outside the zone than of avoiding the loss of deserved strikes. "The whole goal from the onset was to find a way to have the ability to get every pitch that’s in the strike zone called a strike," Flowers says. "Inevitably you’re going to get pitches that are one inch off or one inch below or above the zone."

Flowers, who played for the White Sox from 2009–15, first saw receiving stats on a TV broadcast in 2013 or 2014, via a graphic that displayed a list of the top-five framers over the previous few years. When he went online to compare his own production to those players’, he found that his framing value, while positive, ranked lower than he’d expected it to. Dissatisfied with his stats, he and Chicago’s video specialist studied tape of the top five in search of a common denominator, which they pinpointed as superior performance on pitches at the bottom of the zone, which was then expanding downward as MLB’s PITCHf/x-based Zone Evaluation system encouraged umpires to enforce the rulebook boundary at the bottom of the batter’s knee.

Flowers found that some of the best framing catchers did a good job of anticipating low pitches and positioning their gloves accordingly, while others simply crouched low. He decided to do both. "I changed my setup to get my center of gravity and base lower to the ground, just to create a stronger position for the lower pitches, and I also started to really anticipate low pitches in the zone and how I wanted to catch them," Flowers says.

Since then, he’s kept up his opposition research while paying even closer attention to his own technique. "Every game I catch, I go back and watch typically that night or the next morning," he says. "There’s always a couple pitches in your head that you caught OK, but not exactly how you wanted to." The extra homework is fun for him, because he knows how much it matters. "You don’t know which pitch is going to change the game, but I know one of them is going to change the game," Flowers says.

After years of studies and features hammering home framing’s effects, it’s well accepted that catchers can influence how likely certain pitches are to be called strikes, and that the difference between the worst and best backstops really adds up over thousands of called pitches per season. Even so, some fans object to the notion that catchers should get credit or praise for what amounts to exploiting the fallibility of the umpire’s eye. Read any article about framing, and you’re sure to come across a comment about computerized strike zones. I enjoy the artistry of a catcher who can consistently expand the zone, which makes me anti-robot ump. I’ll admit, though, that it’s not fair to Davis that something happening behind him could have contributed to the call I celebrated above. In some ways, baseball would be better without an amorphous strike zone, but for now, a good catcher’s framing remains a benefit to his team. And no team this year has derived a bigger benefit from one catcher than the Braves have from Flowers, who leads the majors with 15.4 runs saved from framing despite playing less than each of the three next catchers behind him.

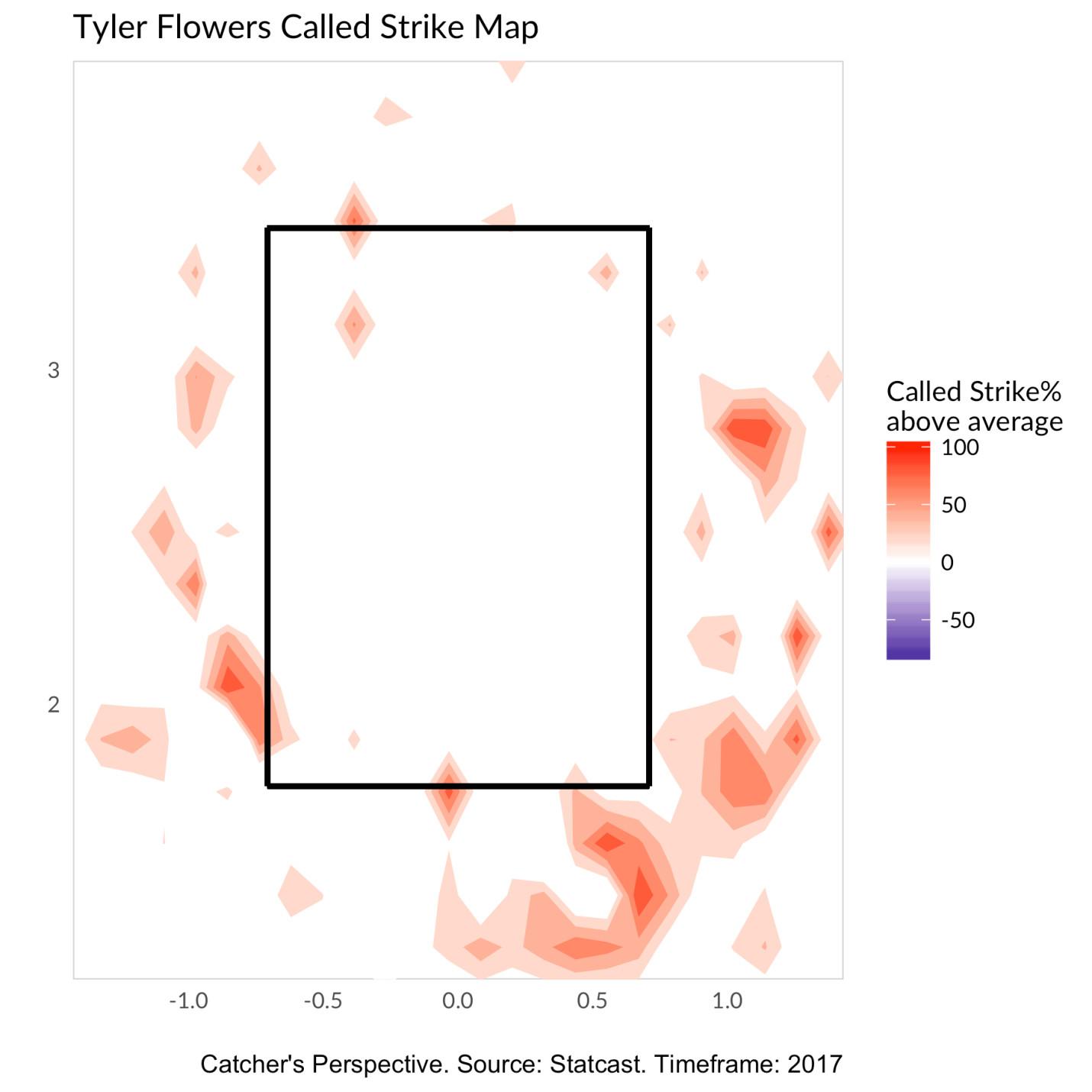

Unless he’s saving secrets for his book, Flowers isn’t attempting to do anything dramatically different behind the plate this year. If anything, he says, he’s simply refined his former methods, becoming cleaner, more consistent, and more accurate. This heat map of his called-strike performance compared with the typical catcher’s (courtesy of FanGraphs’ Jonah Pemstein) shows that he’s been better than average in almost every region on the outskirts of the strike zone.

Framing pitches like the one from Dickey to Davis — located low and away from right-handed hitters — has been Flowers’s specialty this season, as evidenced by his called-strike heat maps on right-handed hitters in 2016 and 2017.

His hottest spot has actually been outside the zone, right where Davis went down. "There is some basic logic that I think a lot of catchers miss," Flowers says. "The deeper you catch that ball, the more it appears to be off the plate away. The further out in front you can catch that ball, the appearance of the pitch seems to be more towards the plate and the break seems to be smaller. … If I let it get in between my legs, the appearance could be another 6 inches lower, versus if I catch it as I’m extending my arm out in front of me."

A montage of Flowers’s highlights this season might be more convincing than any quote or single stat. Pay special attention to the way he positions his arm to oppose the pitch’s movement.

"If you watch a lot of guys, they’ll reach out for a curveball or even fastballs that aren’t straight at their mitt, and it’ll hit their glove and it’ll continue to push their glove further in whichever direction they had to move to get to that pitch," Flowers says. "So the biggest key is to find a way to make an emphasis against the direction of the ball. So, if I’m reaching to the right to catch a fastball, I’ve got to get my glove to the right, before my fastball gets there, and make an effort to go back where the ball is coming from, which would be back to the left."

While this Braves rotation has been better than last year’s, it’s not known for flawless command, so it’s not as if Flowers has had it easy. He’s gotten these calls despite Dickey’s knuckler, a shaky Colón, and the recent arrival of Sean Newcomb, who was wild right up until he teamed up with Flowers. Maybe the most incredible aspect of Flowers’s framing, though, is that he’s doing this at a time when players are improving across the league, making it more difficult for the best to separate themselves from the masses. "The skill set of your major league player has gone up," Flowers says. "Guys seem to be faster and stronger and bigger and kind of mutants." That applies particularly to framing, where we’ve seen the range between the best and worst players, and the variation between teams, shrink rapidly as front offices and coaches have paid greater attention to the skill. "I know teams are definitely putting much more of an emphasis on trying to teach their guys [framing]," Flowers says. "And if they don’t have guys that are ready and guys that are grabbing onto it, I think you’ve seen in the free-agent market, specifically this past offseason, teams targeting those kind of catchers."

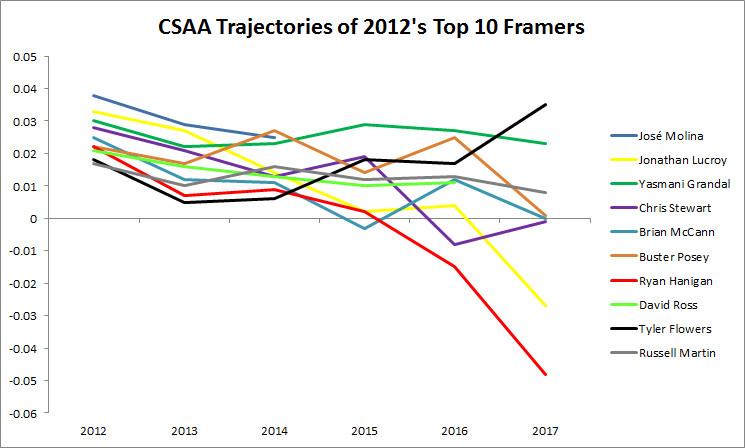

Flowers alone seems immune to the trend toward more modest framing values. The graph below tracks the yearly Called Strikes Above Average rates of the top 10 framing catchers from 2012 (min. 2,500 chances), Flowers included.

José Molina and David Ross have retired, but both fell from their 2012 heights before they stopped playing. Yasmani Grandal is still elite, but he hasn’t returned to his 2012 peak. Russell Martin remains above average, but not by nearly as much. Chris Stewart, Brian McCann, and Buster Posey have sunk to average or slightly below (as has Yadier Molina, who fell just outside 2012’s top 10). Jonathan Lucroy, whose framing decline I detailed in May, has turned into baseball’s worst framer in terms of total runs lost, blaming his pitchers for his own poor performance and prompting the Rangers to dangle him in trades. Hanigan has been even worse on a per-pitch basis.

And then there’s Flowers, the only one of the 10 to be better than he was before the framing gold rush ramped up. In the 10-year pitch-tracking era, we’ve seen only 14 catcher seasons with at least 2,000 framing chances and a Called Strikes Above Average rate of at least .03 (three extra strikes per 100 called pitches), five of which belong to framing master José Molina. Flowers, who’s at .035, is trying for the first such season since 2014.

Flowers also earns rave reviews for the way he’s worked with a staff that’s spanned the extremes of experience, from raw rookies to 40-somethings. "We always liked the way he worked with pitchers," says Braves GM John Coppolella. "He takes such great care to get them through games. Obviously, we were aware of the analytics and how he graded out as an elite performer in terms of framing, and that was nice, but we saw a lot more beyond just the raw numbers." Granted, Flowers isn’t a perfect defender: He’s a below-average blocker, which he attributes to his efforts to stay still and eke out extra strikes. He’s also become one of the worst throwing catchers as he’s aged, nailing only 10 percent of attempted base stealers since the start of 2016, which he blames on wear and tear and a tendency to rush throws to try to make up for not having his former fresh legs and arm strength.

"Of course we all want to throw out every runner and every team wants to give you as much time as possible to be able to throw out every guy," Flowers says. "But the reality is, in my opinion, the much more important part of those situations is throwing strikes, the much more important part is to get the borderline pitch called a strike. Of course I want to throw out as many guys as Salvador Pérez, but with that said, God gave him a much better arm than he gave me. And with that said, Salvador Pérez can’t receive pitches the way I do either, so it’s kind of pick your poison. … In my opinion, the receiving aspect is far more important." BP’s stats support his opinion, appraising Flowers’s framing over the past season-plus as worth almost three wins while docking him only half a win for poor throwing.

There’s one caveat to include here, which also casts doubt on our robot-ump readiness: As MLB has replaced the old PITCHf/x system with Statcast this season, technological hiccups have caused some pitch locations to be recorded inaccurately. The Braves’ new home, SunTrust Park, has been plagued by some of those problems.

"As is the case with any new ballpark and radar-tracking installation, there were bugs to be worked out [at SunTrust Park]," says Pitch Info’s Harry Pavlidis, who’s also the director of technology at Baseball Prospectus. "Unfortunately, due to the late construction (I assume), the extent of issues in SunTrust didn’t become known until close to Opening Day. There was a lot of interference evident, such that pitch movement and location could be off by several inches, or even a foot or more. Later in the season, the system was noticeably better."

In time, some of the early-season data could be discarded or revised, which might change Flowers’s framing ratings — not from great to bad or average, but perhaps to slightly less great. Suzuki’s framing stats, in the same setting, are still below average. And as I’ve followed Flowers’s stats since early June his framing numbers have only improved, even as the system at SunTrust has worked out its kinks.

Flowers isn’t worried that more publicity for his framing skills could come back to bite him. Although staying on umpires’ good sides is part of his preference for not calling what he does "stealing strikes," Flowers doesn’t think that umpires can consciously penalize catchers who earn reputations as strong framers, a factor that some have speculated could be behind Lucroy’s steep defensive descent. "I don’t believe that the umpires can decipher between me and Salvador Pérez and and flip-flop their zone from half-inning to half-inning," he says. "If anything, I feel like the majority of time I get compliments in the positive direction, where umpires have told me they feel like I make it easier for them to be accurate and correct."

Even if Flowers’s framing stats were to regress, his newfound offense would make him an asset. "He’s worked hard to improve his body," says Coppolella. "This guy is ripped and an absolute horse. The other thing is, he’s worked so hard with our hitting coaches, Kevin Seitzer and Jose Castro, on making adjustments, and he’s seeing success from that hard work."

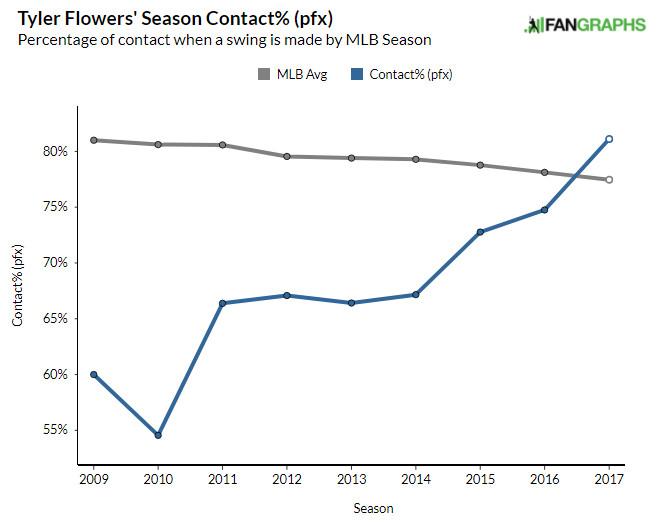

Seitzer has long earned accolades from the statistically inclined crowd, and Flowers is his latest success story. The catcher hasn’t altered his batted-ball profile or started swinging for the fences to try to take advantage of a ball that seems to be flying farther. ("Maybe I’m missing the boat on this one," he says when asked about the so-called "air-ball revolution.") Instead, he’s started making more contact. Among hitters with at least 200 plate appearances this year and 300 PA last year, only four have upped their contact rates more than Flowers has. Steady gains have finally pushed his once-lowly contact rate across the league-average line.

Flowers gives some of the credit to a leg-kick he debuted almost on a whim while leading off against Mets reliever Jim Henderson last June 18. "I just kind of said ‘Screw it, I’m going for it,’ you know?" I just wanted to do something different. And I did a decent leg-kick first-pitch heater. Classic ambush situation, and I went for it. And I hit a lined-shot-left-center home run, so I thought to myself, ‘Man, that was easy power right there. And this leg kick thing is pretty cool.’"

In 143 plate appearances last season prior to that game, Flowers had posted a 91 wRC+ with a 69 percent contact rate. In 178 plate appearances thereafter, he leg-kicked his way to a 118 wRC+ with a 79 percent contact rate. "Kind of like the pitch-framing thing, it’s something black and white I can define my timing with," Flowers says. "There’s a literal time where I want to be in certain spots within that leg-kick that again, through studying or watching other guys doing it, I found to be the common denominator. We often refer to things within our swings by clicks, referring to the click of a mouse, a frame of video. So I want to be at the top of my leg-kick in one click going down before the pitcher releases the ball. … It took me until the leg-kick to actually have any sort of definition of my own personal timing, whereas before I guess it was just raw ability."

Although the leg-kick is the most visible change in Flowers’s swing, he’s even faster to salute a tweak in approach instituted by Seitzer. "I’m looking for a pitch in the middle part of the plate and I’m trying to drive it up the middle," Flowers says. "The more you’re looking pull and looking to go opposite field, the more your swing subconsciously and literally starts going in that direction. … But all of a sudden when I started trying to think, ‘up the middle, up the middle,’ my bat path gave me much more margin for error in terms of the depth and distance out in front [so] I could still get some barrel on the pitches." Flowers hasn’t actually found the middle more often, but maybe the mindset has made a difference.

Flowers, a native Georgian who was drafted by the Braves, now plays close to his four kids. Being home, working with Seitzer, and finally not being a backup have all helped make him more valuable on the field and happier when he’s home.

"Last season was the first time I played professional baseball at the major league level and had fun throughout the whole season," Flowers says. "And of course it’s easier to have fun when you’re having success, but it’s also easier to have fun when you have an idea of what you’re doing, both hitting and catching. … Before that, it was a grind. I got to the point where I believed my ceiling was a .240 hitter in my good years. When you believe that, it’s hard to have fun every day. And it’s hard to be optimistic about the future."

Flowers might not finish the year among the best players in baseball; both his BABIP and his framing could drift downward, and he’ll turn 32 before he reports to spring training next season. But optimism is easier for Flowers now — as, it seems, is almost everything else.

All stats except Flowers’s slash line through Tuesday’s games.