It cost the Red Sox the best prospect in baseball (plus three other players) to acquire Chris Sale last December. Sale, who’d spent his whole career with the White Sox, was widely deemed to be well worth the price after finishing among the top six pitchers in AL Cy Young voting for five consecutive seasons. But his most recent season stood out from the others in one potentially worrisome way.

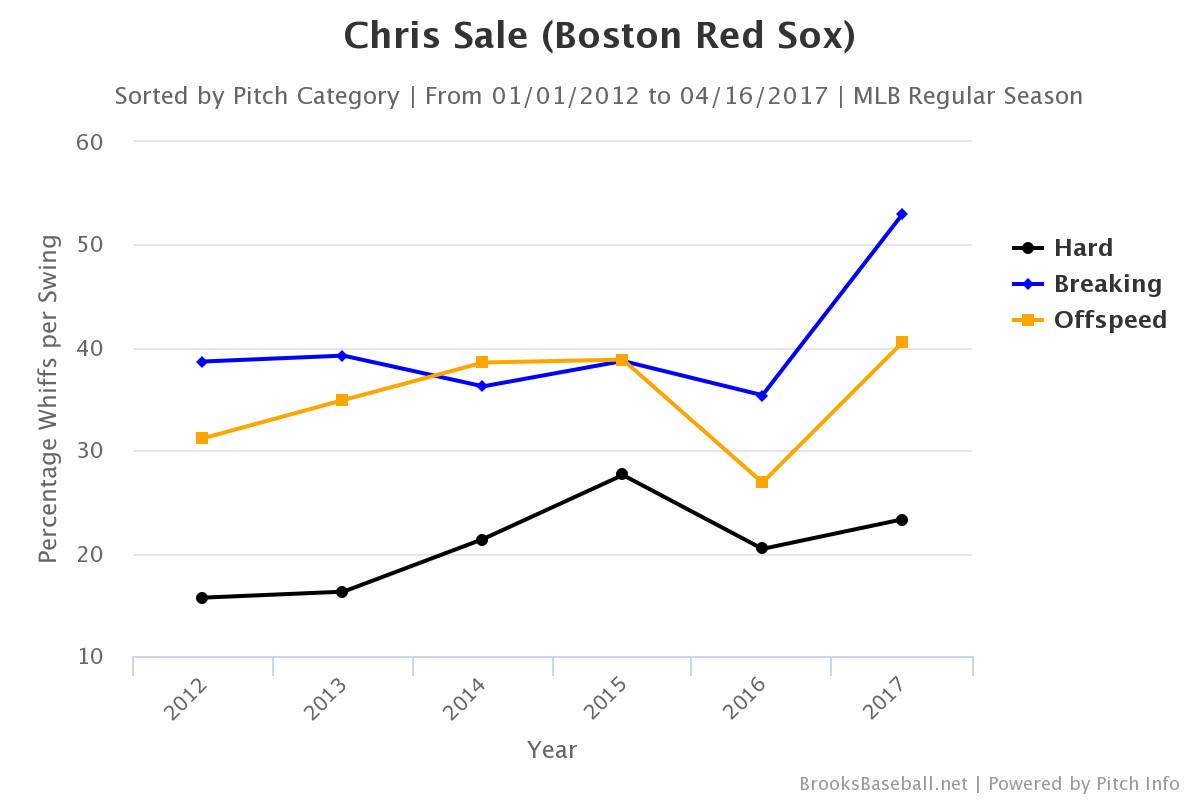

Last spring, Sale and White Sox pitching coach Don Cooper drew up an altered approach, even though the lefty was fresh off what some stats suggested had been his best year yet. Instead of trying to miss bats — which he’d done more often than all but two other qualified starters in 2015 — Sale would rely on his natural movement in 2016 and save his strength by dialing down his fastball speed, throwing fewer breaking balls, and trying to induce more contact, which he hoped would allow him to go deeper into games. That tradeoff has backfired for other strikeout pitchers; although strikeouts, on average, do require more pitches than outs on balls in play, pitching to contact may ultimately increase pitch counts, because balls in play less reliably result in outs.

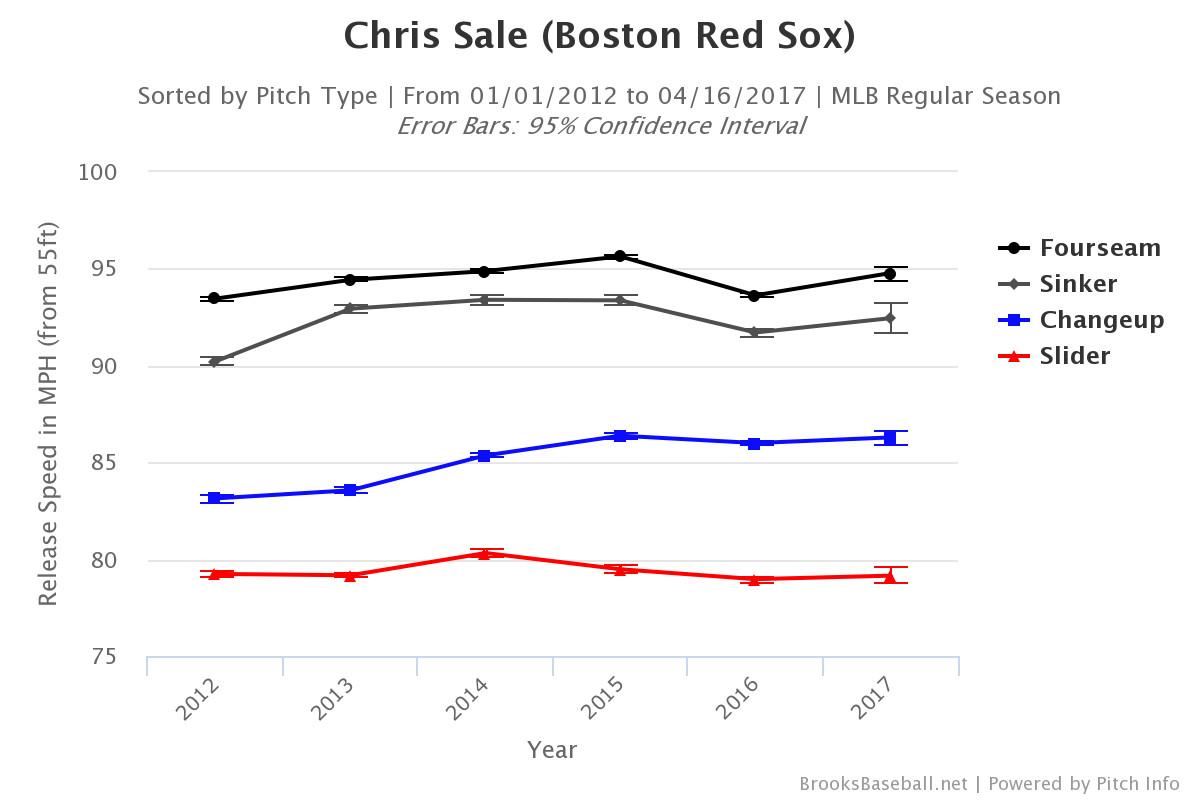

In Sale’s case, though, the plan seemed to pay off in greater durability. He made a career-high 32 starts and threw a career-high 226 2/3 innings with a major league–leading six complete games, and for the first time in any of his seasons as a starter, he didn’t lose a single day to injury. But slowing his fastball by an average of two miles per hour and pounding the zone reduced his dominance on a per-batter basis, as he recorded a career-low strikeout rate (relative to the league) and allowed home runs at a higher rate than ever, which resulted in his worst-ever park-adjusted FIP. (His catchers’ awful framing performance didn’t help, either.) All in all, Sale was probably a little less valuable in 2016 than he’d been in some previous seasons, despite his increased inning count; his Baseball-Reference WAR was lower than it had been in each season from 2012 to 2014.

In light of that deviation from his standard stat line, it wasn’t clear which version of Sale the Red Sox had obtained. Last season’s Sale was still among the best pitchers in baseball, but eroding speeds and strikeout rates are usually indicators of decline. From afar, it seemed possible that Sale’s pitch-to-contact approach was a response to slipping skills as much as it was an intentional tactic. Maybe Sale, who turned 28 this past March, was making concessions to age and accumulated wear and tear from thousands of repetitions of his unorthodox delivery. And maybe Boston would get more of an innings eater than an unhittable ace.

Based on the early returns, there’s no cause for concern: Thus far, Sale has resembled his old self more than the 2016 model. Through three starts, he’s struck out 36.7 percent of the hitters he’s faced, which ranks second in the majors among players with at least 10 innings pitched. He’s already recorded two double-digit strikeout starts, half as many as he had all of last season. Nor has he had any trouble going deep into games, averaging nearly 7 1/3 innings per start, slightly longer than his 7.1-inning average from 2016. Pirates, Tigers, and Rays hitters have seen so many of their swings come up empty that Sale hasn’t had to work hard.

Sale has had a throwback start to the season because he’s evolved (or devolved) in two noteworthy ways. First, he’s gone back to using his devastating secondary stuff. And second, when he has thrown his fastball, he hasn’t eased off the gas as often.

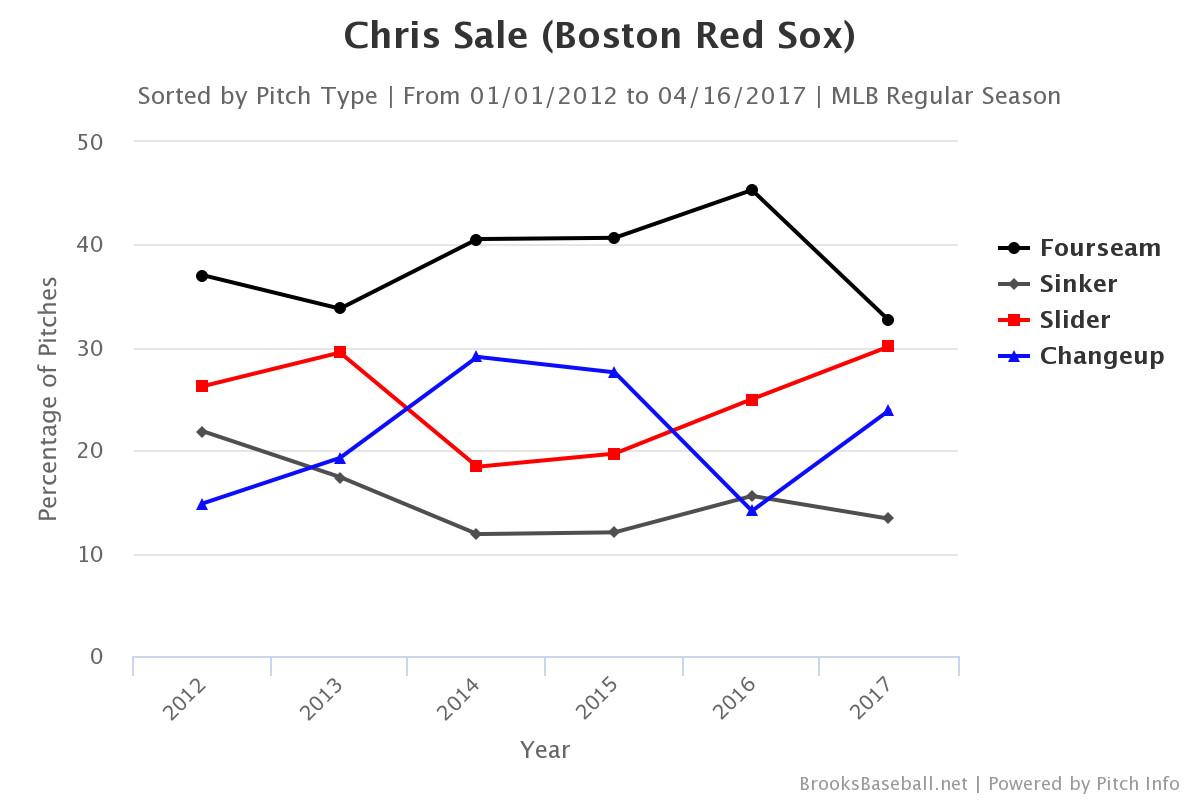

Over Sale’s first five seasons as a starter (2012–16), only Cole Hamels’s changeup was worth more than Sale’s, as measured by FanGraphs’ cumulative pitch run values. But in aiming for contact last season, Sale went away from the change, throwing it roughly half as often as he had in the previous two seasons — 14.1 percent of the time, a career low since he’s been a starter. He made up much of the difference with fastballs, throwing four-seamers and sinkers more than 60 percent of the time.

This season, Sale’s changeup is back, and he’s thrown his slider — another wipeout pitch whose cumulative run value ranked 13th in baseball over Sale’s first five seasons as a starter — as often as he ever has as a starter. Meanwhile, his four-seamer has grown increasingly scarce.

According to Red Sox vice president of pitching development (and assistant pitching coach) Brian Bannister, Sale is a go-with-the-flow sort of starter who lets his catchers take control. "Chris’s approach is to throw whatever the catcher calls because he feels that he can beat a hitter with any of his pitches if he simply executes," Bannister says via email. "He’d rather keep a good rhythm and stay aggressive on the mound than overthink the situation."

This season, Sale’s catcher has been Sandy León. "The change in his pitch percentages is more likely a result of Sandy, who has a knack for mixing creatively, coming up with different sequences than Chris has thrown in the past, and to a lesser extent a byproduct of our organizational pitching philosophies in general," Bannister says.

When Sale has thrown his four-seamer, he’s done so at a more consistent speed. Sale’s fastball is up by about a mile per hour, on average, but it’s not because he’s maxing out any higher than he has in the past. (Actually, he’s topped out a little lower.)

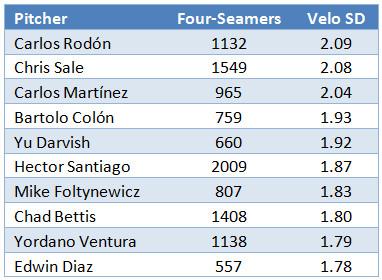

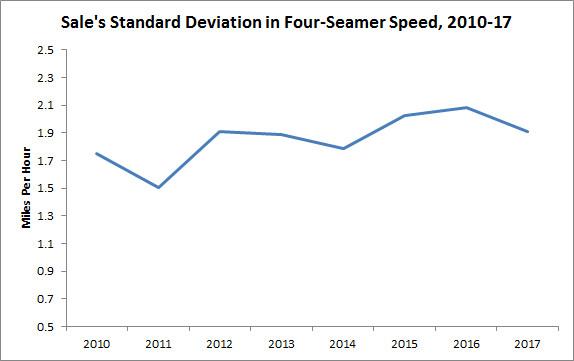

Instead, his fastball speed has been more stable. Of the 206 pitchers who threw at least 500 four-seamers in 2016, only one — then White Sox teammate Carlos Rodon — had a higher standard deviation in four-seamer speed than Sale. In other words, Sale’s fastball measurements weren’t clustered closely around his velocity baseline, which partly reflected his tendency to add and subtract speed.

Even this season, Sale has continued to throw some of the sneaky, batting-practice-type fastballs in the 89–90 range that he’s mixed in more often as he’s completed the time-honored transition from thrower to pitcher. On the whole, though, his fastball speeds have varied less than they did in either of the past two seasons.

Last spring, Chicago catcher Dioner Navarro said that Sale’s pursuit of efficiency was "a good mindset to use your stuff more wisely and save your stuff and bullets for October and November." With the White Sox, Sale didn’t need the extra ammo. With the Red Sox, he probably will. But he doesn’t seem to be holding anything back, and it doesn’t seem to be tiring him; through three starts, his average of 108 pitches per start is up by only a half-pitch compared to 2016.

Red Sox president of baseball operations Dave Dombrowski wagered the franchise’s future when he exchanged a package of prospects whose combination of talent and low salaries were worth nine figures in expected surplus value for a single starter who was coming off a strong but anomalous season. We’re many years away from a complete accounting of that trade, but the Red Sox have to be happy with the way their prized pitcher’s season has started. Sale seems as nasty as ever — and even nastier than the ace the White Sox sent away.

Thanks to Jonathan Judge and Rob McQuown of Baseball Prospectus and Jeff Zimmerman of FanGraphs for research assistance.