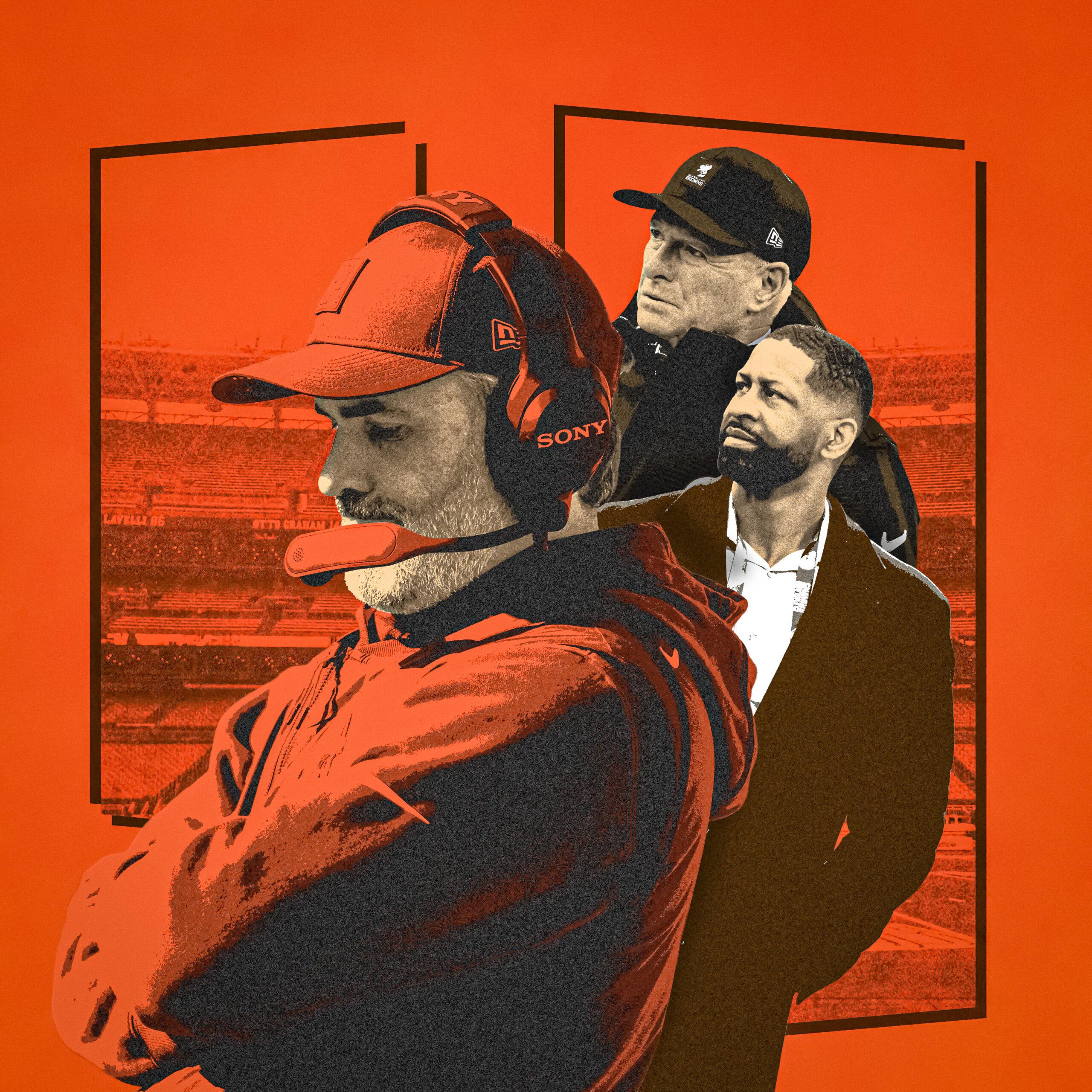

On Monday morning the Cleveland Browns fired head coach Kevin Stefanski after a six-year tenure that included two Coach of the Year wins and Cleveland’s first playoff win in more than 25 years. Despite those accolades, Stefanski exits with a 45-56 record, and he went just 8-26 in the last two seasons. But as is often true of the Browns, quarterback turmoil—especially since they traded away Baker Mayfield, the player Stefanski had the majority of his success with, in 2022—hangs over the team and Jimmy Haslam’s decision.

The list of passers since 2022, if you don’t have the jersey handy:

- Deshaun Watson

- Jacoby Brissett

- Joe Flacco

- Jameis Winston

- Shedeur Sanders

- Dillon Gabriel

- Dorian Thompson-Robinson

- P.J. Walker

- Jeff Driskel

- Bailey Zappe

General manager Andrew Berry, who brought all of those players to Cleveland, is keeping his job and will have a major role in the search for a new coach, Haslam said. Browns!

As was the case with Mayfield, who has made the playoffs twice since the Browns traded him, Stefanski looks immediately primed to win the breakup. Though he may be Cleveland’s scapegoat, Stefanski instantly becomes one of the most attractive candidates in a coaching cycle with relatively weak options, while the Browns look like one of the worst landing spots available for other prospective head coaches. If Stefanski had no prior connection to Cleveland, he’d probably be considered out of the Browns’ league.

That’s not to say Stefanski’s record is pristine. He is an offensive head coach, and the Browns have been near the rock bottom of the league in most offensive categories for two years running. They finished this season 31st in scoring, 30th in yards per game, and 30th in turnovers. Last season, they were last in scoring, 28th in yards per game, and tied for 31st in turnovers. Despite Stefanski’s work with quarterbacks being a supposed strength, he’s had a shaky relationship with Sanders, and he has never seemed like the most galvanizing force for an organization that often appears downtrodden. On Sunday, after ending the season with a win against the Bengals, Sanders, being positive, said that Stefanski’s coaching has been “real tough.”

But again, this needs context. Given a choice between coaching and roster management as a place to pin the Browns’ failures, it’s roster management all the way. That starts with Haslam’s decision to invest the team’s future in Watson in 2022, and you could make a solid argument that it ends there as well, since that trade and the contract that came with it have capped Cleveland’s potential and hamstrung Stefanski’s ability to lead ever since.

Even after winning 11 games and making the playoffs in 2023, behind a 4-1 record under Flacco down the stretch, Stefanski was reportedly pushed to overhaul his staff and fire his first offensive coordinator, Alex Van Pelt, in favor of coaches that Haslam and Berry felt would play to Watson’s strengths in 2024. Few of those moves worked out; both new offensive coordinator Ken Dorsey and offensive line coach Andy Dickerson were fired after just one season.

Meanwhile, Watson has not been able to stay on the field and has been one of the worst quarterbacks in football when he has played. With his albatross of a contract and without the three first-round draft picks they gave up to trade for him, the Browns have had limited resources to spend on the rest of the roster. But even with those restrictions, the team’s decisions have been suboptimal.

After the offense was terrible in 2024, the Browns spent their top two draft picks on defensive players last spring. Cleveland then went through four left tackles and at least 10 different starting offensive line combinations this season and had some of the worst receiver play in the NFL. Midway through each of the past two seasons, Stefanski has surrendered play calling duties in an attempt to find an offensive spark.

At quarterback, the Browns traded away both Flacco, who’d played well for them in 2023 and was named the starter at the beginning of this season, and Kenny Pickett before the midseason mark. That left the offense in the hands of two rookies, third-rounder Dillon Gabriel and fifth-round pick Sanders, who was thrust into the starting role when Gabriel suffered a concussion in Week 11.

A controversial draft pick to begin with, Sanders had no work with the starting offense in training camp or practice during the season before entering the lineup, both a symptom of the Browns’ quarterback carousel and a sign that his coaches had modest belief in his potential. The incongruity of those choices—moving on from veteran QBs who would not be part of the team’s future but not preparing their potential successors—suggests that the coaching staff and front office were out of sync, which is not a new problem in Cleveland. The friction over the past few years, perceived or real, could be explained by the original tension of how far this franchise had to go to justify the Watson trade and contract and paper over their consequences.

So why is Stefanski the one to go and not Berry? The usual reason coaching turnover is more rapid than general manager turnover: It’s easier for a GM to get and stay close to ownership. Perhaps because they’re tied together by the Watson trade, Berry and Haslam seem to be operating together, which is why Haslam spent part of Monday morning quibbling with Cleveland reporters about Berry’s scouting record. The Browns also value their scouting and analytics infrastructure, which Berry oversees, making him hard, at least in theory, to cut loose. Stefanski’s standing may have been further weakened when Paul DePodesta, the Browns’ chief strategy officer who was an original advocate for his hiring, left the Browns in November to return to working in baseball as head of the Colorado Rockies.

Even if Stefanski is the one taking the fall, the coaching marketplace probably won’t hold him accountable for Cleveland’s recent failures. It’s easy to see the Titans developing an interest in Stefanski as a steward of Cam Ward. The Giants could be enamored of his experience. Profile-wise, Stefanski benefits from having been around long enough that teams will believe he knows how to run an organization while still having some new-school cred with teams that want a more modern football mind. He’s a bit like a rizz-less Mike Vrabel from last year. This year, with a shallow pool of candidates, that’s probably enough to be a hot name.

Meanwhile, the Browns will have to woo a new coach to a team that has no clear long-term answer at quarterback and an entrenched personnel regime that seems to call more shots than the coaching staff. The two highest-paid players on the roster are Watson and Myles Garrett, the latter of whom requested a trade less than a year ago and stayed only after Haslam cut him a giant check. Offensive lineman Joel Bitonio, a core leader at a position of need, may retire this offseason. There are major holes across the offensive line and at receiver. Oh, and the team still owes Watson, who didn’t play in 2025 while recovering from multiple surgeries to repair an injured Achilles tendon, $46 million—and if they cut him, they’ll take on $131 million in dead cap charges.

It’s amazing how much that trade (and the contract that followed) continues to cost the Browns. It is the original sin of this era of the franchise, and the architects of the original move have multiplied its costs by refusing to admit it was an epic failure long after it clearly proved to be one. People were always going to get fired because of this.

Maybe a fresh start will be good for all parties here, but it’s hard to look at Stefanski’s firing without concluding it had something to do with his inability to make an unworkable situation work. He’s probably the happiest man in football holding a pink slip today. And the Browns are still the Browns.