In his seminal New Yorker essay about Ted Williams, John Updike wrote, “Gods do not answer letters.” As a general rule, neither do owners of high-profile professional sports franchises. Dick Monfort does. The owner of the Colorado Rockies, a team that stands as the exception to so many rules, regularly replies to emails from fans, with a signature that specifies his answer was sent from an iPad or iPhone.

Most of Monfort’s responses are innocuous acknowledgements of facetious suggestions to, say, sign Juan Soto or trade for Shohei Ohtani, but he occasionally loses his cool. In 2014, Monfort fired off this testy response to one unsatisfied fan: “By the way you talk maybe Denver doesn't deserve a franchise, maybe time for it to find a new home.” Later, he apologized and attempted to do damage control: “What I meant to say was maybe we, the owners, don't deserve a franchise.”

Maybe Monfort doesn’t deserve a franchise. The Rockies are one of two teams that’s never won a division, along with their fellow 1993 expansion club, the Marlins—and the Marlins have won two titles, whereas the Rockies got swept in their one World Series trip in 2007. But Monfort still runs the Rockies, and he still answers emails from fans. (“Will see what happens,” he wrote in response to a recent pitch to trade for Tarik Skubal.) Monfort probably shouldn’t do this—billion-dollar businesses employ public-relations professionals for a reason—but I hope he never stops. That Monfort’s suggestion (in)box is always open is the Rockies in microcosm: well-intentioned but bumbling, and, for better or worse (most likely the latter), out of step with the way every other team operates.

At least, until now. The Rockies are trying to reform, and they’ve entrusted their future to an old name and a new hire who has an unusual, un-Rockies-like resume: former Moneyball whiz kid Paul DePodesta. Only the Rockies could modernize by hiring a blast from the past. Could MLB’s worst team be about to make up for lost time? Is the league in danger of losing its laughingstock? Might Monfort start marking those messages as spam? DePodesta, Michael Lewis wrote in 2003, “was fascinated by irrationality, and the opportunities it created in human affairs for anyone who resisted it.” Running the Rockies should create ample opportunities for resistance.

In a sea of conformist front offices that largely evaluate players the same way, pursue similar acquisition strategies (with varying degrees of success), and speak in soporific buzzwords, the Rockies have been baseball’s last bastion of “fuck it, we ball.” Most contemporary teams carry themselves with a sort of superficial competence that makes them difficult to dunk on, compared to the clueless sad sacks of yore. The Rockies are refreshingly unabashed about being different. All evidence suggests they don’t know what they’re doing. But they’re definitely doing their own thing.

In the first of a few deep dives into Rockies front-office dysfunction that The Athletic has published over the past few years, a rival executive said, “They are one of the weirdest front offices to deal with. (We’re) never really close to being on the same page on any concept we talk about. My feeling is they’re very insular.” Like one of Darwin’s finches, they’ve evolved distinctive (though not always adaptive) traits. Of course, suggesting that the Rockies reside on their own island undersells their idiosyncrasy. “They’re really on another planet right now,” another rival executive said last month. That’s more like it.

The Rockies aren’t crusaders or iconoclasts; they’re not trying to change the world. But they have historically refused to let the world change them, which is kind of endearing. Not really for Rockies fans, to be clear, but for neutrals who rubberneck at backward ballclubs. “My favorite part of it is they think they are doing a good job,” said an unnamed evaluator in yet another Rockies takedown this spring. “They question everyone else doing things differently.” In May, then-GM Bill Schmidt essentially expressed that sentiment himself: “People talk about us being isolated. That’s fine. I wouldn’t say we’re behind the times by any means.” Maybe every other team is ahead of its time, and the Rockies are right where they should be.

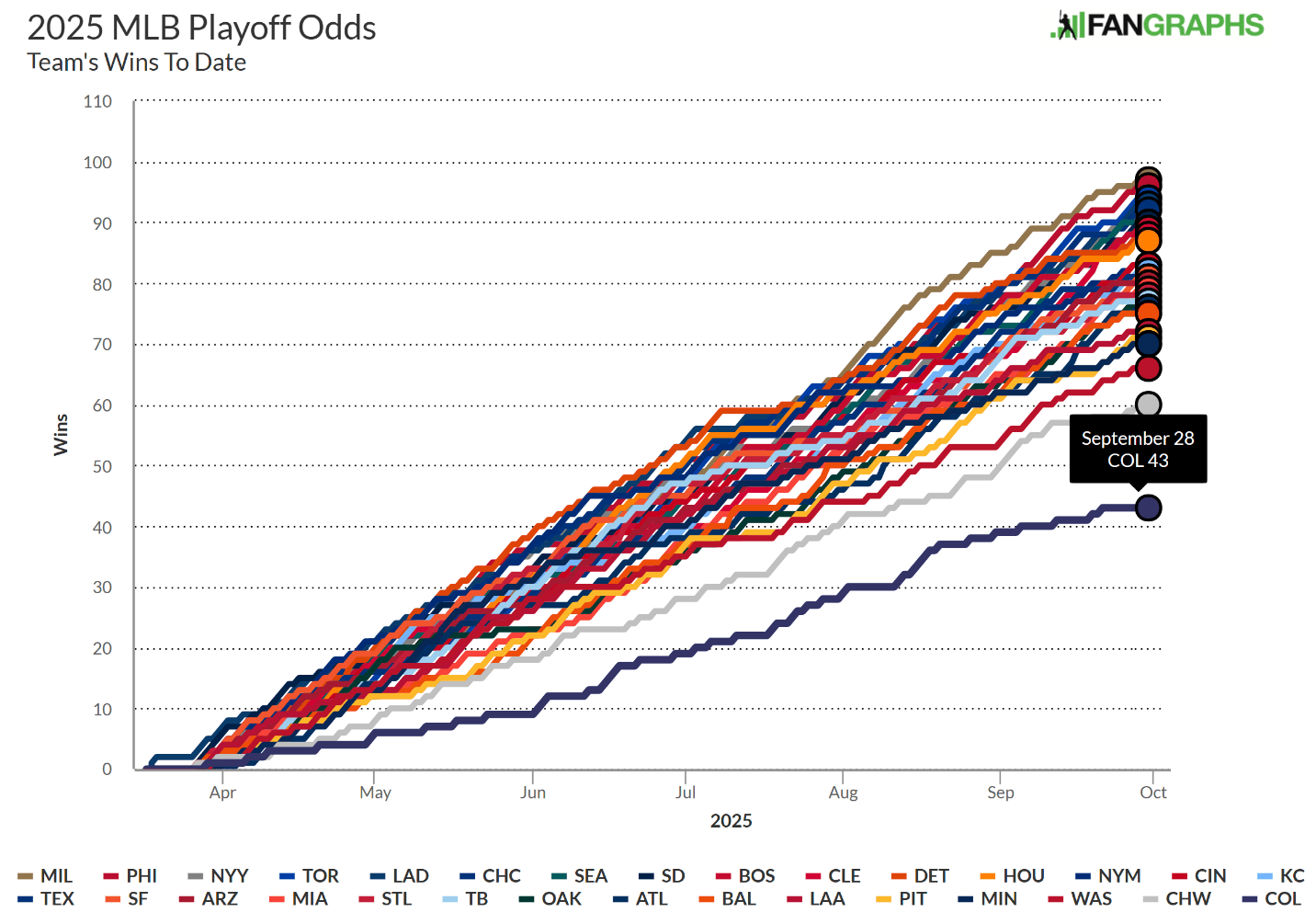

Probably not, though. The Rockies lead baseball in losses since 2018 (their last playoff appearance) and narrowly trail the Royals and Pirates for the most losses since Colorado’s debut season. They’re coming off three straight 100-plus-loss seasons, including this year’s 43-119 showing, which nearly unseated the 121-loss 2024 White Sox on the single-season leaderboard. (They blew away the Sox—and every other non-19th-century team—by being outscored by 424 runs.) The Rockies’ Twitter account, with plenty of practice, has perfected the art of memeing about being blown out. Denver’s altitude, and the attendant hangovers that haunt Rockies hitters as they acclimate to mile-high movement versus sea-level movement, gives the Rockies a built-in excuse for struggling, but not to this degree. To sum up the state of the Rockies’ roster, a Moneyball (and Friends) quote comes to mind.

On the bright side, Coors Field is lovely, the beer is cheap (sometimes), and the mascot is a delight who doesn’t deserve to be tackled. (Just make sure you clearly enunciate his name.) The Rockies managed to maintain middle-of-the-pack attendance this year in spite of a historically terrible team, perhaps in part because Coors visitors could drown their sorrows at baseball’s best rooftop bar. “If product and experience that bad don’t come!”, Monfort emailed a displeased fan in 2014. The product is abysmal, but the experience keeps putting people in the seats, even if most of them root for the road team. From afar, the spectating isn’t as scenic, but the team’s singular style still provokes curiosity. The Rockies are quaint.

I don’t want to overromanticize the Rockies, or Monfort, who inherited a meatpacking and distribution fortune from his father, became vice chairman of the Rockies in 1997, and teamed up with his brother to buy the team in 2005 before taking sole control as owner/chairman and CEO in 2011. Monfort is one of only a handful of MLB owners who haven’t cracked the three-comma club, making him a throwback to a time when sports owners were merely megarich, not ultrarich. Relatedly, he chaired the owners committee during the 2022 CBA negotiations and has advocated for a salary cap that would restrict spending not only on players, but also on organizational infrastructure.

However, as a percentage of the Rockies’ revenue, their overall valuation, or his own net worth, Monfort’s spending tends to be pretty robust. The Rockies haven’t had a grievance filed against them by the MLBPA (a low bar, but one the Marlins, A’s, Rays, and Pirates haven’t cleared). Monfort spends; he just tends to splurge on the likes of Ian Desmond (–1.3 fWAR for the Rockies) and Kris Bryant (–1.8 fWAR and counting, kind of). A’s owner John Fisher is incompetent and callous, and Pirates owner Bob Nutting is incompetent and miserly. Monfort is merely incompetent. In a study from this summer of fan sentiment on team subreddits, Monfort didn’t quite crack the top five most-hated MLB owners. Rare Rockies win! Maybe it helps that the Rockies don’t have Paul Skenes–caliber stars (or Pirates-quality prospects) whom their fans are frustrated to see squandered.

Monfort also seemingly isn’t a terrible boss, if only because a job with the Rockies is akin to a lifetime appointment. By his own admission, he’s a little too loyal, which explains why the Rockies’ offices at Coors Field have stayed stocked with staffers whose tenures with the team predate the humidor. Thus, although the Rockies aren’t good relative to other teams—far from it—they might, adjusted for league-average ownership evil, qualify as chaotic good; to borrow one definition of the D&D alignment, they “usually intend to do the right thing, but their methods are generally disorganized and often out of sync with the rest of society.”

That’s the Rockies to a T. They’re the sports equivalent of the Louvre heist—a colossal screw-up in which nobody gets seriously hurt and we all get to joke about how it happened. (The password to the Louvre’s video surveillance system was reportedly “Louvre”; the Rockies are run by nepo babies of nepo babies, and during the pandemic the team made front-office analysts double as clubhouse attendants.) “How nice to read about a heist rather than a massacre,” Caity Weaver wrote about the burglary. How nice to snark about a team that’s bad by accident rather than as part of a tanking/penny-pinching plan. The Rockies may get massacred competitively, but they come by their losses legitimately. I feel bad for their fans, but the Rockies are tremendous content.

So it was with a mixture of relief and trepidation that I detected tremors of a Rockies revolution this season, even as the team was suffering daily indignities on the field. In May, after the team fell to 6-31, Denver native and Rockies lifer Kyle Freeland, who holds the franchise record for games started, said of the Rockies’ early season opponents, “What they’re doing is right. What we’re doing is wrong.” A few days later, Bud Black—the winningest manager in Rockies history, albeit with a .441 winning percentage—was fired. (Such is the power of Rockies recidivism that I barely batted an eye when, one month later, Black was rumored to be a “strong candidate” for Rockies pitching director.) Then came the rumors of a forthcoming front-office shakeup—a disturbingly un-Rockies concept.

On October 1, Schmidt resigned as GM, followed a week later by assistant GM Zack Rosenthal. (The departed duo took with them almost half a century of combined Colorado service.) The news about Schmidt was announced alongside this statement from the team: “The Rockies will begin an external search for a new head of baseball operations immediately.” That sounded like a … good idea? No, worse: It was the rhetoric of a typical modern team that talks about best practices.

“We’re looking for someone that can come in here, put their eyes on our operation, compare it to operations that have been successful elsewhere around Major League Baseball, and help us architect an operation that can reinvent the way we go about things in order to narrow the gap,” Rockies EVP Walker Monfort (no relati—just kidding, he’s Dick’s son) said. In the same story, the Rockies’ beat writer for MLB.com declared, “This much is known as the Rockies seek new baseball leadership: They are going to be different.” But becoming different from the familiar Rockies would inevitably make the club less different from the other teams. Smart. Sensible. Boring! Was this the end of the sui generis Rockies, the lone club carrying the torch from the era when outsiders not only thought they could do a better job of running a team than the people in charge, but were probably right?

I shouldn’t have doubted them—by which I mean, I shouldn’t have considered not doubting them. Because although they did make good on their goal of going outside the organization, they did it in one of the weirdest ways possible: by going outside the sport entirely. The Rockies hired DePodesta, of late the chief strategy officer of noted non-baseball team the Cleveland Browns.

Give the Rockies credit: They did at first flirt with making a more conventional move. They reportedly surveyed several respected baseball execs, including former Twins GM Thad Levine and Jays VP (and former Rays VP and Astros GM) James Click, and they wound up with two finalists: Diamondbacks assistant GM Amiel Sawdaye and Guardians assistant GM Matt Forman. Nothing seemed strange about that process, as reported to that point, aside from the fact that for the Rockies, an absence of strangeness is itself bizarre.

Then the team’s inherent Rockies-ness reasserted itself; even on their best behavior, the Rockies couldn’t keep passing for normal. According to multiple reporters, Sawdaye rejected an offer, and Forman pulled out, seemingly leaving the Rockies free of finalists days before this week’s GM meetings. Two reports said that one perplexing sticking point was the Rockies’ reluctance to embark on a full front-office makeover until after a new CBA is in place (which won’t happen for a least a year).

Soon, a report surfaced that Dick Monfort had talked to Adam Ottavino about the top job—as in, the former Rockies reliever who pitched for the Yankees this year and hasn’t technically retired yet as a player. (Ex-player GMs may be making a comeback, but moving from the mound to the GM’s office with no front-office steps in between would be wild.) Meanwhile, the team claimed a player on waivers a few days after a fan with the Twitter handle “@BasebaIIExpert” emailed Monfort to suggest the move, raising the tantalizing prospect of doing away with the front office and conducting baseball business based on tips from the public. How could the outcome be worse than the second-worst team WAR total of the modern era? (Well, it could be the worst team WAR total, which barely belongs to the ’54 A’s.)

Early into an offseason of surprising managerial hires—a college coach; a catcher and reliever three years out of uniform with zero combined coaching or managing experience; a 33-year-old member of a previously unsuspected branch of Buteras—the Rockies said “hold my Coors” and reestablished their supremacy in the realm of surprising personnel moves. The jokes wrote themselves: Finally, the Rockies read Moneyball … The Rockies tried to hire Peter Brand, discovered he didn’t exist, and settled for the closest equivalent … When the Rockies are ready to hire a manager, Kevin Stefanski could be available.

Only in comparison to Ottavino and front-office-by-fan could the Rockies’ actual hire seem semi-predictable. For one thing, DePodesta had been working for maybe the most benighted franchise in football, which has won the fourth-fewest games in the NFL since he was hired in 2016 and which engineered one of the worst sports transactions of all time on his watch. (While DePodesta probably didn’t instigate the Deshaun Watson trade—which is believed to have been more of a blunder by owner Jimmy Haslam, GM Andrew Berry, and head coach Stefanski—he did defend the team’s inadequate due diligence.) It’s extremely Rockies that after Walker Monfort talked about bringing in someone who could school his behind-the-curve club on other competitive teams’ practices, he and his dad hired somebody from the Browns. (In fairness to Monfort, when he said “Cleveland is an example” of a team Colorado could learn from, he didn’t specify which Cleveland team.)

Not only has DePodesta—the former Dodgers GM and A’s, Padres, and Mets exec—been out of baseball entirely for almost a decade, but he also hasn’t run a team for two decades. Last month marked the 20th anniversary of his firing as Dodgers GM, after less than two years in the job. When the 2026 season starts, DePodesta’s 21-year gap between campaigns as head of a baseball operations department—his new title is president of baseball operations, which allows me to dub him DePoBO—will be 50 percent longer than any previous executive’s in the Baseball-Reference database.

You Again? Longest Gaps Between Seasons as Head of Baseball Operations

Granted, DePodesta’s outlier listing is partly a testament to how precocious a front-office prospect he once was. Had Billy Beane left the A’s to run the Red Sox in 2002, his assistant GM, a 29-year-old DePodesta, would have taken his place. When the Dodgers hired DePo in 2004, he was, at 31, one of the youngest GMs ever. (Even after his long interlude out of the spotlight, he’s only 52.) And admittedly, there are some success stories on that table above, from Gene Michael (who assembled the foundation of the Yankees dynasty while George Steinbrenner was temporarily banned from baseball) to John McHale and Dan Duquette (who took the Expos and Orioles, respectively, to the playoffs) to Bill Stoneman (who delivered the Angels’ first championship) to DePodesta’s predecessor in Oakland and boss in San Diego and New York, Sandy Alderson (who presided over a Mets pennant).

On the flip side, there’s the Whitey Herzog precedent. Herzog is known primarily as a Hall of Fame manager, but he had two stints as GM with the Cardinals and Angels, more than a decade apart. The second stint, in Anaheim, didn’t go great. “He had a great deal of respect and recognition among his peers,” an agent said of Herzog in 1994, “but the reality now is that this is a different era, and he hasn’t crossed the bridge.”

DePodesta returns to baseball-ops power in an era that’s almost unrecognizably different from the one that greeted him his first time around, when dinosaurs still roamed sports, and the sports pages. Back then, DePodesta was labeled—bullied as, even—“Google Boy” by a newspaper columnist who’s no longer alive. (Heck, newspaper columns are barely alive, though those that are still aren’t kind to DePodesta.) Even compared to 2016, when DePodesta left the Mets, the game done changed: There are new rules; new technological tools; new data sources. In 2004, another columnist called DePodesta a “computer nerd” who “speaks in megabytes.” Thanks to Statcast, DePo will have to speak in terabytes today.

Rip Van Winkle fell asleep for 20 years and missed the American Revolution; DePodesta left the sport and missed much of its player-development revolution. Though he hasn’t missed it entirely: Last week, DePodesta said “I have always kept my eye on baseball,” which is certainly one of the prerequisites for running a baseball team.

“I’ll admit, there’s some boldness to this,” Dodgers owner Frank McCourt said when he hired DePodesta in 2004. “But that’s exactly what we need to do to change things around here.” The Monforts could say the same today. But it doesn’t seem like the best-equipped candidate to jump-start the Rockies would be someone who has to play catch-up himself. Then again, I guess DePodesta and the Rockies can learn and grow together.

DePodesta isn’t the first Harvard guy to take a stab at this assignment (former Rockies GM Jeff Bridich played baseball for the Crimson, too), but he is Colorado’s first external hire since Dan O’Dowd in 1999—and O’Dowd wasn’t a Monfort addition. (No wonder Walker referred to the team’s groundbreaking “hire an outsider” strategy as a “unique situation”—which, in a way, DePodesta’s unprecedented, time-capsule comeback turned out to be.) In fact, before Schmidt resigned, only four men (inclusive of Schmidt) had held his role in franchise history. The only teams to have fewer heads of baseball ops over the same span were the Yankees—who haven’t had a losing season since 1992—the Guardians, and DePodesta’s old team, the A’s. DePodesta got a raw deal with the Dodgers, but if there’s one thing the Rockies don’t do, it’s run people out of town too quickly.

For DePodesta, that low turnover rate could be a double-edged sword. The challenge of conquering Coors Field appeals to baseball’s bright minds (including DePodesta’s), but organizational inertia, coupled with Monfort’s meddling, keeps DePo’s new gig from being a “dream job.” His performance will partly depend on how much latitude he’s given to fire, hire, and beef up the Rockies’ resources. They may have a performance lab and a Trajekt Arc pitching machine, but they’re not really about that bleeding-edge life; they’ve consistently employed one of MLB’s smallest R&D departments and parted ways with its leaders. The Rockies aren’t that far removed from Ottavino having to coach his own pitching coach on the value of high-speed cameras in spring training, or Rockies minor leaguers having to sneak illicit looks at stats and teach each other how to apply them because the club didn’t condone data-driven training.

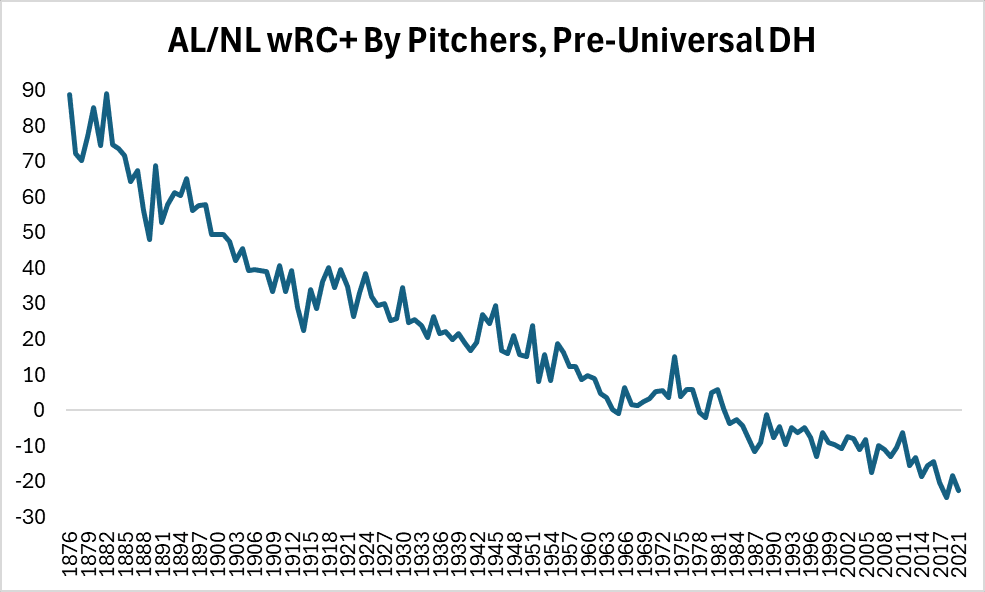

One thing we lost when pitchers stopped hitting was a quick way to tell how the caliber of baseball had climbed over time. Pitchers gradually got worse on offense relative to the league not because they got less athletic, but because they didn’t improve at the pace of dedicated hitters, who were selected for their skill at the plate and who constantly pushed to improve it.

The plight of the Rockies, who hadn’t lost more than 98 games in a season before being humbled from 2023 on, is similar: They didn’t get dumber, but baseball got smarter around them. They’re a benchmark by which we can measure the rest of the league.

“I have always tried to be open, friendly, and understanding,” Monfort said in 2014. “Obviously, at times I have failed.” Monfort has failed—if not at being friendly, then at putting the right people in place to build a winning team. The Rockies might be doomed until he surrenders the reins, but he has a chance to change course now, and the support and autonomy he provides his new PoBO may matter more than hiring DePodesta did. That’s the only way we’ll find out whether the sport has passed by the guy who once was ahead of the game.

“What gets me really excited about a guy is when he has warts, and everyone knows he has warts, and the warts just don’t matter,” DePodesta said in Moneyball. As a baseball executive in 2025, DePodesta’s warts are well known. Whether they’ll matter is not.

A wise sabermetrician once said, “You gain more by not being stupid than you do by being smart.” If the Rockies are ready to do the former—if not necessarily the latter—then to paraphrase something a pitcher once said: Don’t look back. The Rockies might be gaining on you. Just, you know, not quickly. Their competition has a huge head start.

The Rockies could be the last of their kind, an endling staving off sports extinction. There will always be good teams and bad teams, rich teams and poor teams, well-run teams and mismanaged teams. But if DePodesta drags the Rockies into the present, we may never see a team that’s so stuck in the Stone Age again. I would welcome a Rocktober redux featuring the few promising Rockies on the roster right now—Ezequiel Tovar, Hunter Goodman, Chase Dollander—plus prospects Ethan Holliday and Charlie Condon. But there is something special about a sports punchline that 29 fan bases share.

In Dick Monfort’s heart, hope springs eternal. In 2020, he predicted that the Rockies would win 94 games; the pandemic prevented us from finding out for sure, but of the 60 games they did play, the Rockies lost 34. In 2023, he said, “I think we can play .500 ball.” His team finished 59-103. In 2025, he initially refused to be baited—“No predictions here,” he told the writers ruefully—but he couldn’t help himself. The infield, he claimed, “will be the best defense, maybe in the history of the game.” It was, as he conceded, “a big statement”: The infield defense ended up below average. (This is more subjective, but I’d say he also struck out when he claimed the 2025 squad would be “fun team to watch.”)

It would bode well for the Rockies if, for once, Monfort has conceded defeat. In Moneyball, DePodesta said of the A’s opponents, “I hope they continue to believe that our way doesn’t work. It buys us a few more years.” The Rockies’ problem was believing that their way did work. If bottoming out has disabused them of that notion, then their new way may buy them better years ahead. And if not, then in the Rockies and Dick Monfort, Moneyball may meet its match.

Thanks to Kenny Jackelen of Baseball-Reference for research assistance.