“The idea of photographing a cellphone is just death,” Robert Eggers said earlier this year, and as long as he keeps making portentous horror period pieces (next up: 13th-century werewolves!), he should be able to keep his lunch down. Scrolling through my picks for the most arresting and affecting cinematic images of 2025, though, I couldn’t help but notice how many of them involved cellphones, computer screens, and other pieces of consumer-grade technology—a sign of filmmakers doing their best not to turn a blind eye to the times, but to meet the multimedia gaze head-on. As usual with this annual project, the goal isn’t so much to choose the most beautiful or most “perfect” frames of the year as to spotlight moments that distilled something larger about either the movies they appeared in or the world beyond the frame. I also tried to create at least a bit of variance between the selections here and the movies on my 10-best list, although there are a few titles pulling double duty.

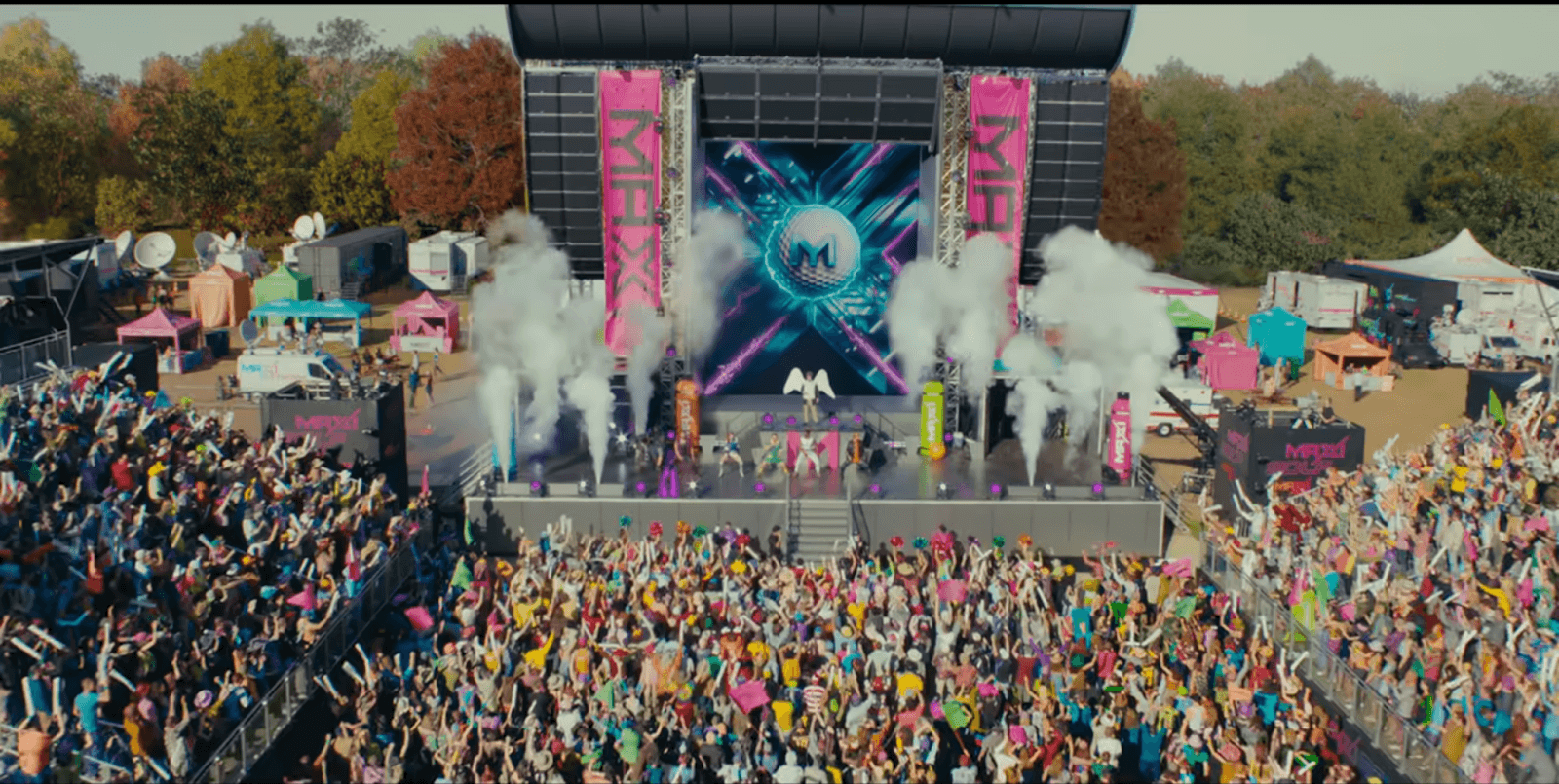

(Dis?)honorable Mention: Happy Gilmore 2

Directed by Kyle Newacheck, Cinematography by Zak Mulligan

To be clear, I’m very fond of Happy Gilmore 2, which isn’t a good movie by any means. It exists somewhere beyond good and evil, to paraphrase Nietzsche—it’s slop that goes down easy, a vanity project defined by its star’s winning and sincere sense of self-deprectation. (Lest anybody suspect that Adam Sandler doesn’t know the difference between fake movies and real ones, check out his amazing work in Jay Kelly, a movie I actually liked less.) The most striking thing about Happy Gilmore 2 isn’t the roll call of pop cultural cameos or even the thick, greasy residue of nostalgia; it’s how unbelievably ugly it looks. So ugly, in fact, that it almost has to be a satire—the Netflix equivalent of a Trojan horse, skewering Big Streaming’s complete and utter enshittification of the cinematic image. The villain is a manic energy drink magnate (Benny Safdie) trying to drag the PGA kicking and screaming into the TikTok influencer era; the lurid, vomit-flavored color scheme of his MAXI empire suggests a dystopia located on the wrong side of the uncanny valley. By contrast, the original Happy Gilmore—shot on celluloid by Arthur Albert—looks like an 18th-century woodcut. We must RETVRN.

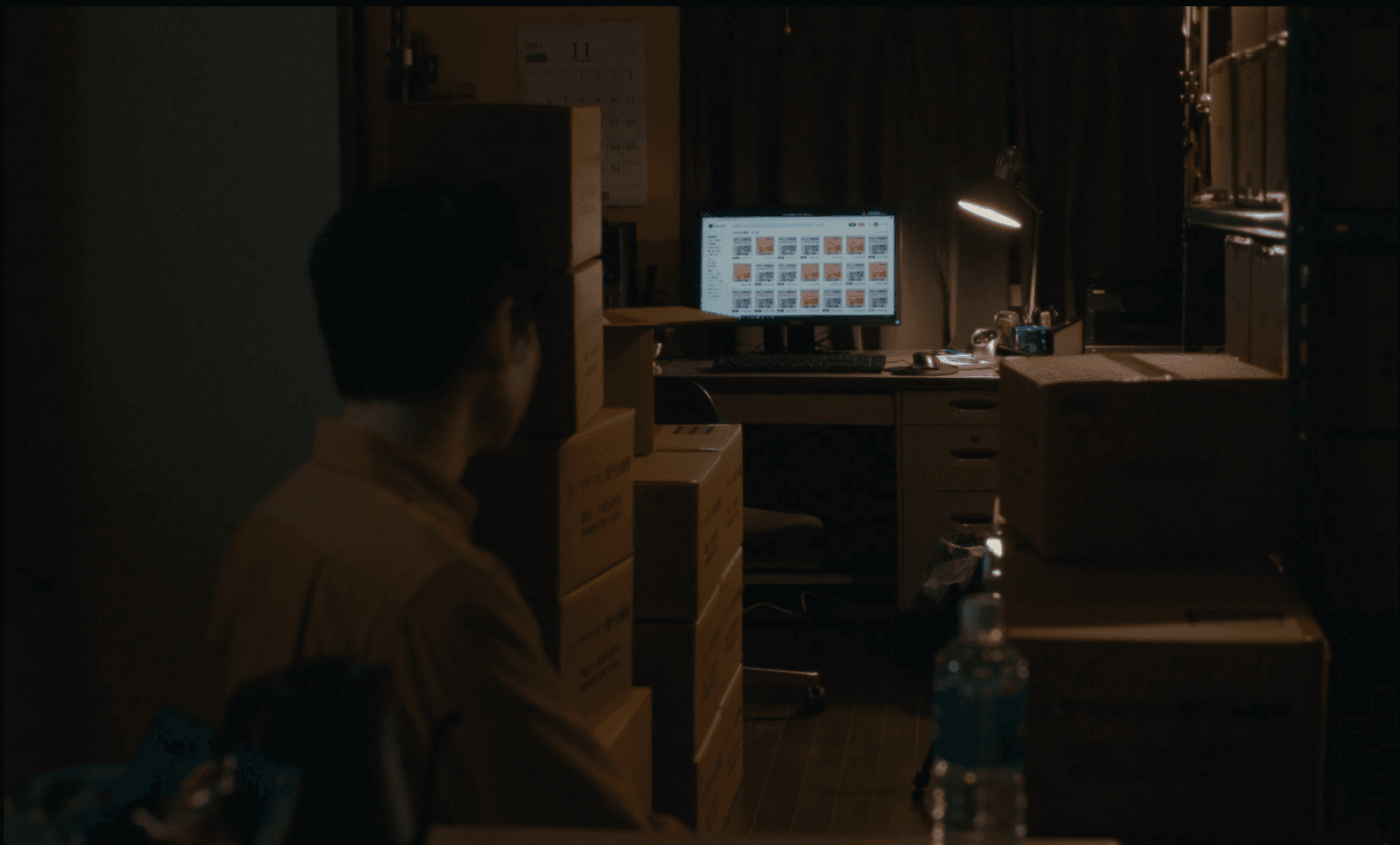

Cloud

Directed by Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Cinematography by Yasuyuki Sasaki

The waiting is the hardest part: Sitting patiently by the monitor to see whether his latest cache of marked-up junk has been clicked through, internet reseller Yoshii (Masaki Suda) transforms imperceptibly into a hybrid. He’s at once spectator and puppet master in a late-capitalist drama playing out on flat screens around Tokyo and the entire world. Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cloud is a dark comedy of supply and demand, and without resorting to show-offy camera movements or compositions, the Japanese master gives us a world where every location and exchange feels transactional. There’s a texture of yearning to the images that should be recognizable to anybody who’s ever wondered whether they truly need the items in their online cart or whether they just want them—which is to say that Kurosawa’s film strikes a universal chord.

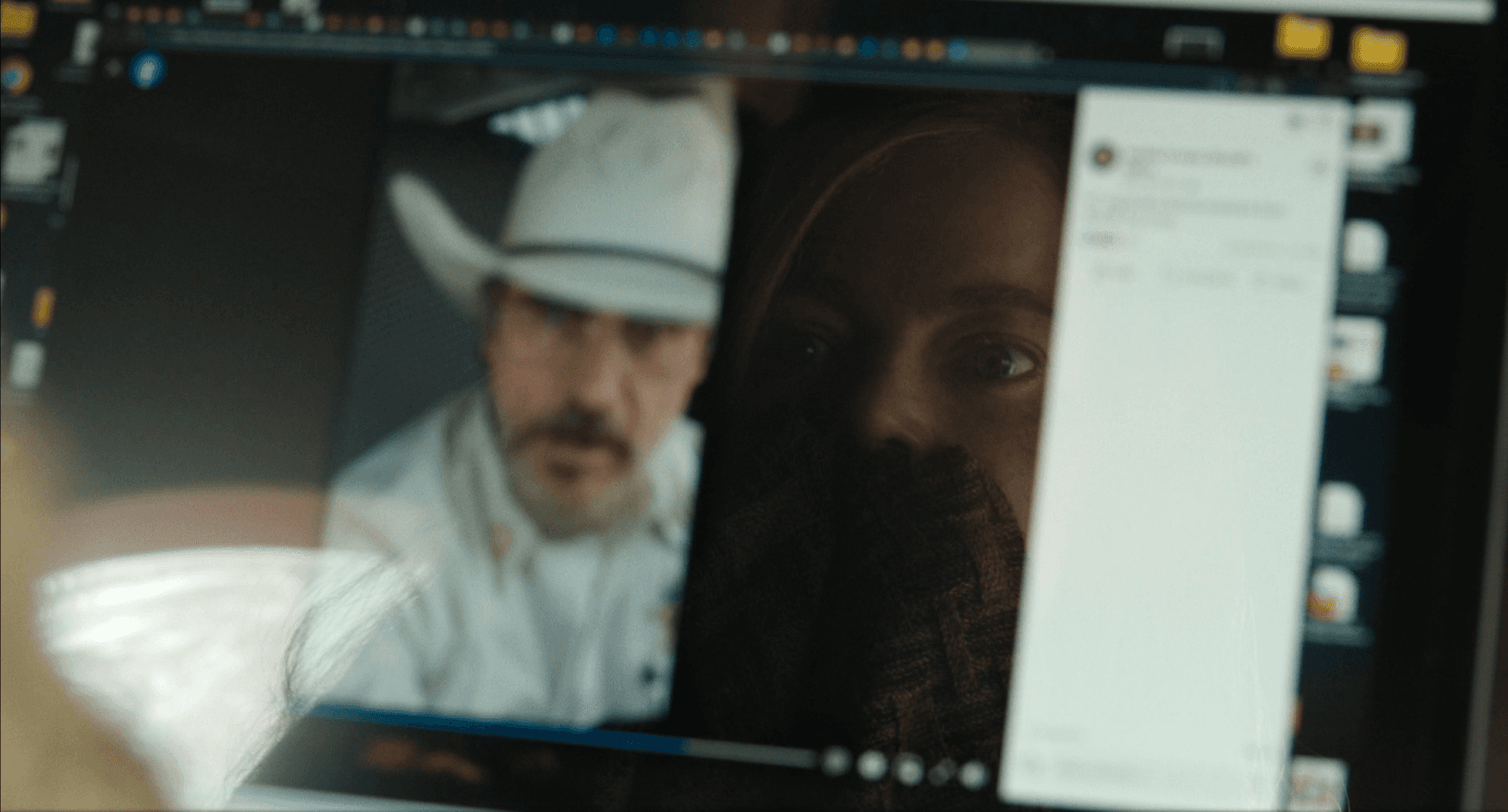

Eddington

Directed by Ari Aster, Cinematography by Darius Khondji

Beneath its strident satire of COVID-era paranoia and protocols, Ari Aster’s Eddington is a movie about compartmentalization; each of its major characters is trapped in their own little ceramic slabs of reality, unable—or unwilling—to tear their gaze away from the black mirror. When Joaquin Phoenix’s Sheriff Joe Cross first announces his mayoral bid, he’s framed dead center in his own iPhone display mounted on a police car dashboard. It’s a clever composition—the windshield glass appears on either side of the vertical screen, suggesting a set of blinders—but Aster complicates it by having Joe’s wife, Louise (Emma Stone), log on to her laptop. Her mortified reflection effectively transforms a selfie into a two-shot—or, depending on how you look at it, a triptych, with her Facebook feed lurking as a character in its own right. That a lot of critics (and viewers) found Eddington annoying is fair enough; it’s an obstreperous poltergeist of a movie about ghosts in the social media machine. But formally speaking, it’s the strongest work of Aster’s career, syncing form to content with finesse and a nasty sense of humor.

The Mastermind

Directed by Kelly Reichardt, Cinematography by Christopher Blauvelt

Throughout Kelly Reichardt’s exquisitely sketched character study The Mastermind, we see JB (Josh O’Connor) looking intently at paintings and objets d’art. He likes to think of himself as a man with an eye for the finer things. We’re never quite sure whether it’s aestheticism—or just simple, stupid hubris—that motivates our (anti)hero to risk his cozy suburban existence (and his responsibilities as a husband and father) on a harebrained, small-scale museum heist. Whatever the answer, Reichardt exacerbates JB’s pathos in the aftermath of his scheme by confronting him with images of painterly beauty: The America he skulks through on the lam is suitable for framing. The most striking exhibit is a pair of JB’s shirts, illuminated through the window of the hotel room where he’s hiding out from the cops. They suggest a ghostly sort of duality; a would-be daredevil suspended in midair, the pale, faded traces of a man who’s no longer really there.

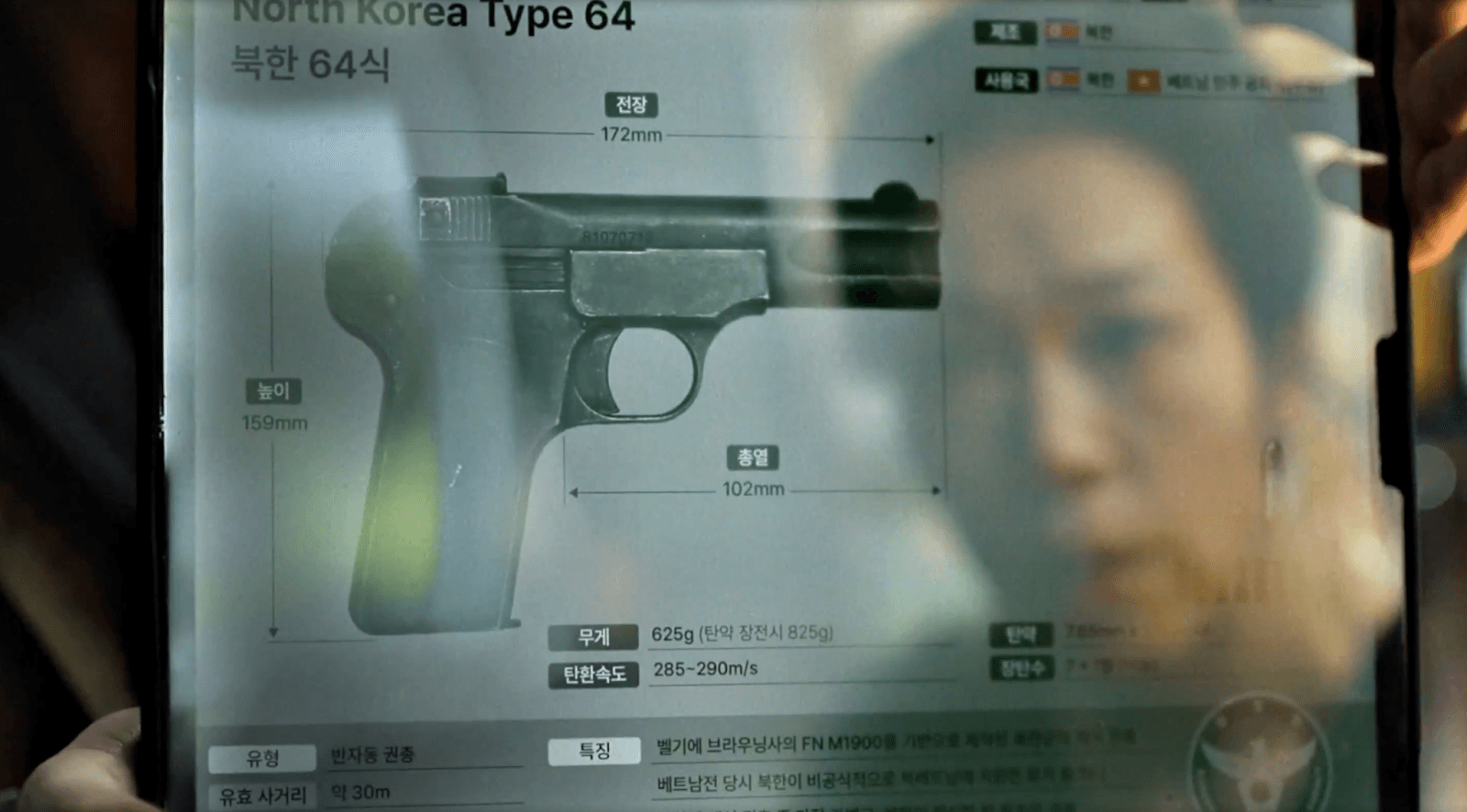

No Other Choice

Directed by Park Chan-wook, Cinematography by Kim Woo-hyung

Three years ago in this very space, I wrote about Park Chan-wook’s swoony neo-noir Decision to Leave as an “example of how directorial imagination can transform conventions into visual coups.” Right now, there’s no filmmaker who’s thinking harder about form, and No Other Choice—about a downsized paper factory manager who starts to take the idea of a cutthroat job market literally—is filled with dazzling, destabilizing visual tricks. It’d require unraveling a lot of narrative threads to explain exactly why the widow played by Yeom Hye-ran is searching through various gun makes and models on an iPad being proffered by cops, but the skill of the filmmaking transcends plot points. Here is the most vivid depiction to date of the anxious, violent psychology of doomscrolling. Even as Yeom’s character is being presented with a kind of get-out-of-jail-free card, Park shows us that she’s just a prisoner of her own device.

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl

Directed by Rungano Nyoni, Cinematography by David Gallego

Objects in the rearview mirror may appear closer than they are: Driving home from a house party in Missy Elliott cosplay, Shula (Susan Chardy) spots the supine body of her uncle Fred lying by the side of the road. He’s dead, but he isn’t gone: Rungano Nyoni’s superb sophomore feature unfolds as a ghost story haunted by the spirit of a patriarchy that preys on its female subjects. Uncle Fred, it seems, was a monster, a fact that keeps slipping through the cracks of all the weeping, wailing testimonials offered up in his wake. Crucially, this is the only time we see him in the flesh—as existential roadkill, as well as a (literal) reflection of a family history that refuses to rest in peace.

One Battle After Another

Directed by Paul Thomas Anderson, Cinematography by Michael Bauman

No American filmmaker locates poetry in motion like Paul Thomas Anderson. The paradox of One Battle After Another is that its most indelible images are the ones that hurtle by at serene velocity. Exhibit A: the silhouetted figures of the “vato skateboarders,” emissaries of the “Latino Harriet Tubman situation” orchestrated by Benicio del Toro’s Sensei Sergio St. Carlos. OBAA is a movie of factions in collision and counterpoint; Sensei’s skaters—all of whom were recruited from El Paso and given free rein to show their stuff—are shot to look as if they’ve leapt off the pages of a graphic novel. They’re so fleet and daring as they bound over and across rooftops in the sanctuary city of Baktan Cross that it’s all Leonardo DiCaprio’s washed dad-bod ex-revolutionary can do to try to keep up. (I could have just as easily gone with the static shot where Bob drops from a great height and splats on the concrete, a more slapstick form of kineticism.) “As skateboarders we’ve kind of always been the underdogs, seen as the outcast or the rebels,” said one member of the quartet, Gilberto Martinez Jr., in an interview with the Los Angeles Times. “But in a way we’re showing freedom, we’re not trying to be put in a box, we express ourselves through this skateboard.” Anderson, meanwhile, expresses himself by elevating his collaborators, however briefly, into Pop Art icons.

Resurrection

Directed by Bi Gan, Cinematography by Jingsong Dong

It’s futile to try to represent the serpentine 36-minute-long take near the end of Bi Gan’s Resurrection via a single screenshot; the selected image could just as easily be wide-angled or intimate, crowded or desolate, deep red or perfect blue. It supposedly took the director and his crew four-plus hours to capture the sequence, which is set on New Year’s Eve 1999 and includes group dancing, karaoke, a shoot-out, vampirism, and a shout-out to F.W. Murnau’s seminal silent classic Sunrise. The most amazing moment involves an outdoor projection of a Lumière brothers short in which the ancient footage somehow plays at regular speed while the crowd milling in front of and around it has been sped up in a time-lapse blur. Bi is nothing if not a showman, and also a stuntman, to the point that he refers to his own practice as a “mission: impossible.” As an almost-final reckoning with the history of cinema, Resurrection is literally death-defying stuff; the sheer complexity and exhilaration of its money shot should confer something like immortality.

The Secret Agent

Directed by Kleber Mendonca Filho, Cinematography by Evgenia Alexandrova

Before Danny Torrance barreled through the corridors of the Overlook Hotel on a Big Wheel in The Shining, a pint-size Antichrist used his trusty trike as a battering ram in The Omen. The mock-Hitchcockian scene in which poor Lee Remick gets thrown off her footstool and over the staircase by her adopted progeny is a bad-taste classic, and Brazilian director Kleber Mendonca Filho gets good mileage by deploying it in his late-’70s period piece, The Secret Agent. There’s a satirical point being scored here via the juxtaposition of an explicitly satanic big-screen antagonist and the all too banal authoritarian evil consolidating power behind closed doors in movie-mad Recife; in a film that keeps forging links between cinephilia and political consciousness, the use of a Hollywood genre movie is more than just a sight gag. Although, speaking of sight gags, there’s a good one in this scene when the camera, approximating the view of Wagner Moura’s dissident hero, pans down to notice one lucky viewer in the balcony receiving oral sex from his seatmate. We come to this place for magic …

The Shrouds

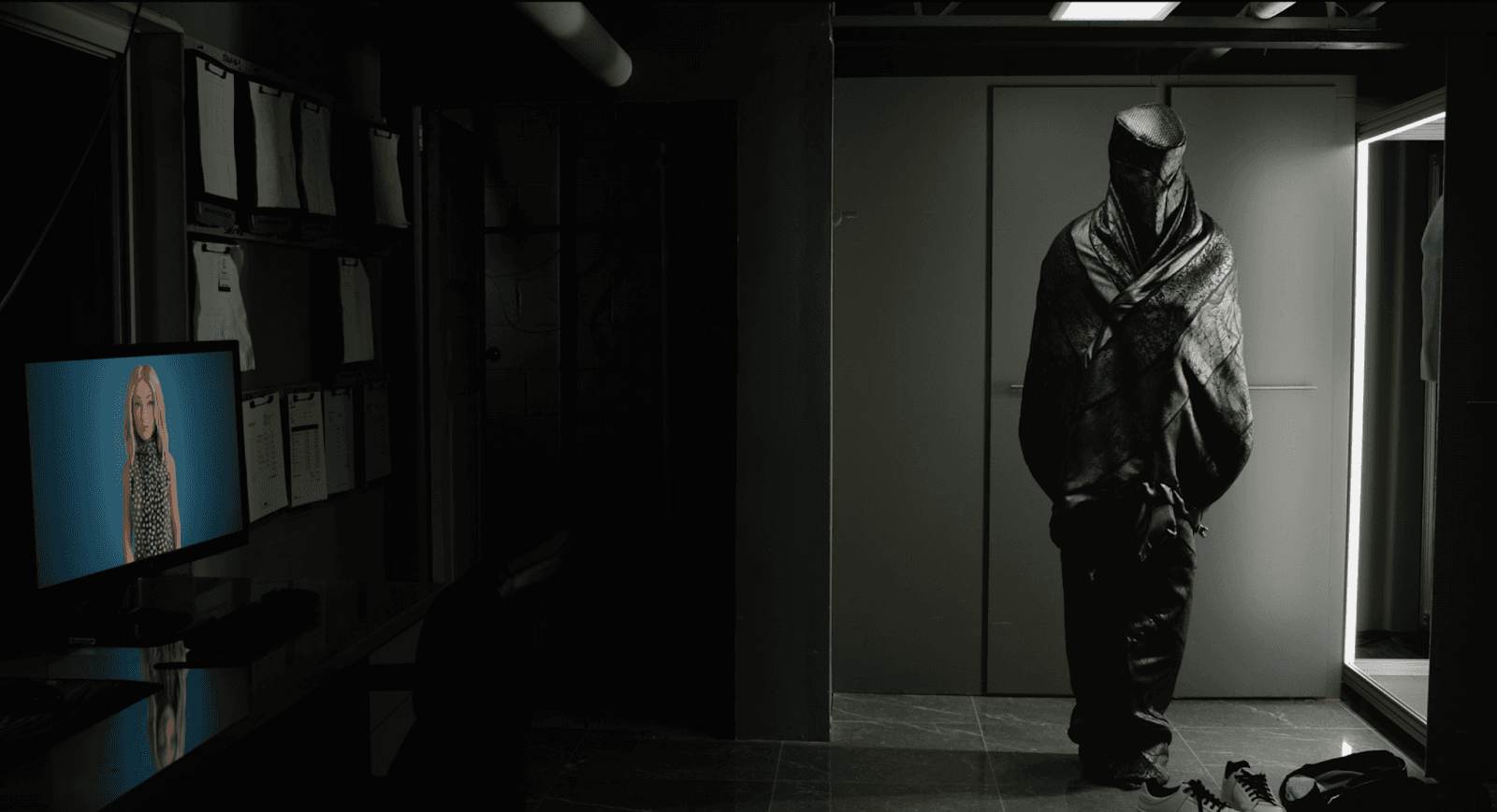

Directed by David Cronenberg, Cinematography by Douglas Koch

The films of David Cronenberg are filled with mad scientists who wind up as the subjects of their own bizarre experiments: Think of Jeff Goldblum zapping himself through the telepod in The Fly or game designer Jennifer Jason Leigh getting exiled into her own virtual video game world in eXistenZ. In The Shrouds, GraveTech impresario Karsh (Vincent Cassel) decides to try out the electronically modified burial garments that have made him a wealthy man. Standing alone in his company’s office, draped in his jet-black chain-mail creation, he cuts a forlorn—and sadly funny—figure, captured by Cronenberg at a clinical but empathetic distance. “I wanted to know what it felt like to be wrapped … to be shrouded,” Karsh tells his customized helper-bot Hunny, who’s been made in the yassified image of his own dearly departed wife, Becca. “It’s not meant for the living,” the AI replies in Becca’s voice, caution and commiseration blended into a single deadpan tone. Some viewers might find The Shrouds’ visual style flatlined, but the simplicity of Cronenberg’s compositions evinces a quiet mastery that his showier inheritors will have to grow into—or else get old trying.

28 Years Later

Directed by Danny Boyle, Cinematography by Anthony Dod Mantle

For my money, Danny Boyle’s 28 Years Later was the most visually inventive movie of the year, leveraging the speed and agility of handheld digital cameras—including multiple iPhones—against an epic 2.76:1 aspect ratio capable of evoking an almost intergalactic sense of grandeur. The mid-film set piece in which the characters played by Aaron Taylor-Johnson and Alfie Williams run for their lives across the Lindisfarne land bridge presents a vision quest gone awry; rarely has a homecoming been staged with such an ardent, life-or-death sense of urgency. The darkened causeway, the indifferent coastline, the hovering specter of the northern lights—this is breathtaking image making, alert to the power of scale in a way that shames most higher-budget blockbusters. In a just world, the ever-resourceful Anthony Dod Mantle would be scooping up cinematography prizes left and right. We’ll see in February whether Nia DaCosta’s sequel The Bone Temple contains anything comparable.

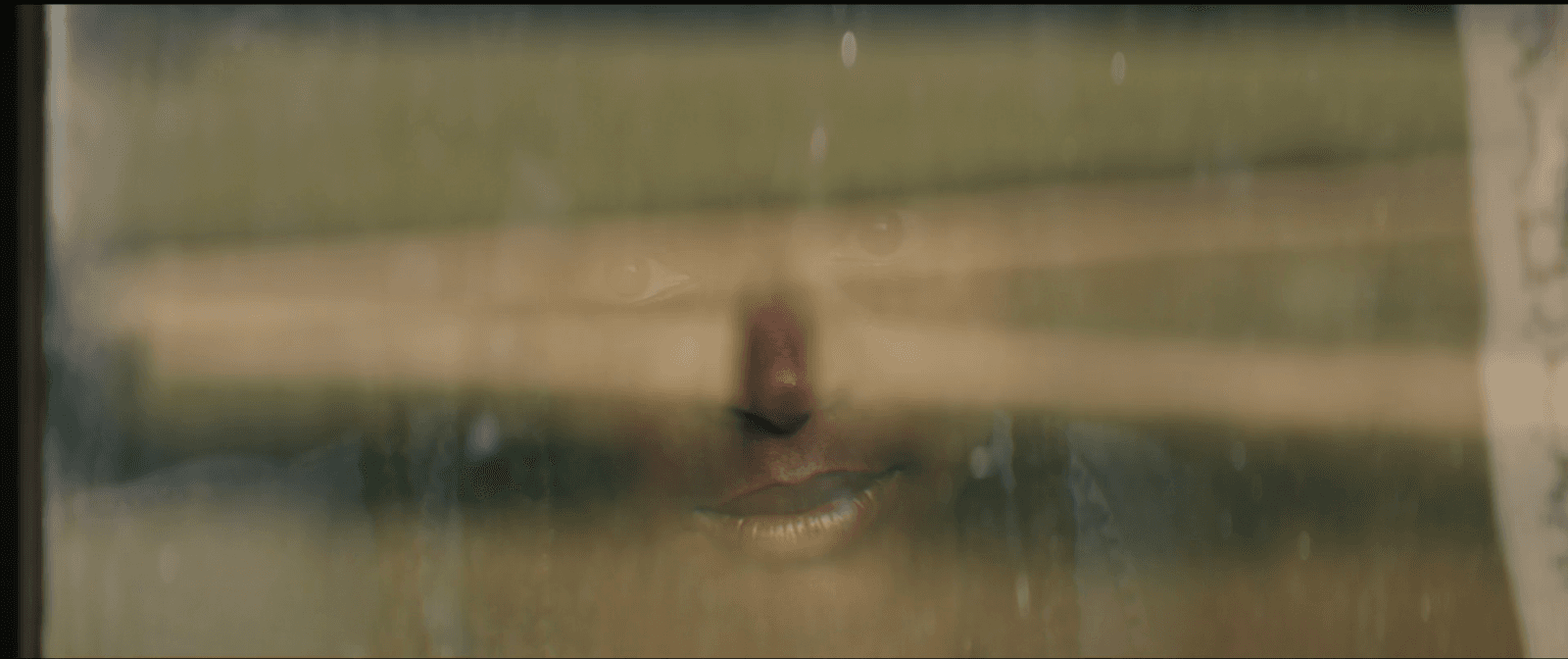

The Woman in the Yard

Directed by Jaume Collet-Serra, Cinematography by Pawel Pogorzelski

You could count the number of contemporary genre directors with better visual instincts than Jaume Collet-Serra on one hand and have a couple of fingers to spare. The only question when it comes to The Woman in the Yard—which was not even screened for critics by its myopic distributor—is what shot to select as an avatar for his artistry. Here, a POV shot belonging to Ramona (Danielle Deadwyler) transubstantiates via a shift in focus into a numinous close-up; meanwhile, the subject of her gaze—the titular woman in the yard—becomes absorbed into her face, setting up a connection that shapes and deepens the meaning of the film’s ensuing mise-en-scène. It’s getting old having to remind people that JCS is the real deal, but as long as movies as sophisticated, heartfelt, and actually scary as The Woman in the Yard languish in Dumpuary purgatory, it’s worth trying to call attention to the work—which, once seen, speaks on its own behalf.