Wrestling legend Terry Gene Bollea, known worldwide as Hulk Hogan, died after suffering cardiac arrest at his home in Clearwater, Florida, on Thursday at age 71. The man who urged millions during the 1980s to "say your prayers and eat your vitamins" passed away around 11:17 a.m. at Morton Plant Hospital, surrounded by family members. His death marks the end of a long, wildly successful era for professional wrestling, closing the book on a career that transformed the sport from regional attraction to global phenomenon. His passing also brings renewed attention to the many controversies that surrounded Hogan, including a leaked sex tape that spurred a lawsuit that arguably changed digital media and revealed racist remarks that tarnished Hogan's carefully crafted image.

Born on August 11, 1953, in Augusta, Georgia, to construction foreman Pietro “Pete” Bollea and homemaker Ruth Bollea (nee Moody), Terry’s journey from overweight, bullied child to global icon reads like quintessential American mythology. The family moved to Port Tampa, Florida, when Terry was just 18 months old, establishing the Gulf Coast roots that would define his identity throughout his life.

The idea that Terry Bollea would become a professional wrestler—let alone one of the greatest of all time—seemed implausible to those who knew him as a child. In the March 29, 1985, edition of The Tampa Tribune, Bollea’s mother explained to reporter Tom McEwen how her son had rejected contact sports. “He was always very big,” she said. “At 12, he weighed 190. He was serious about the guitar and studied it religiously. The band, Ruckus, was a good one and he was doing well [as a student at the University of] South Florida and in music when he decided to sell all his equipment and go into wrestling.”

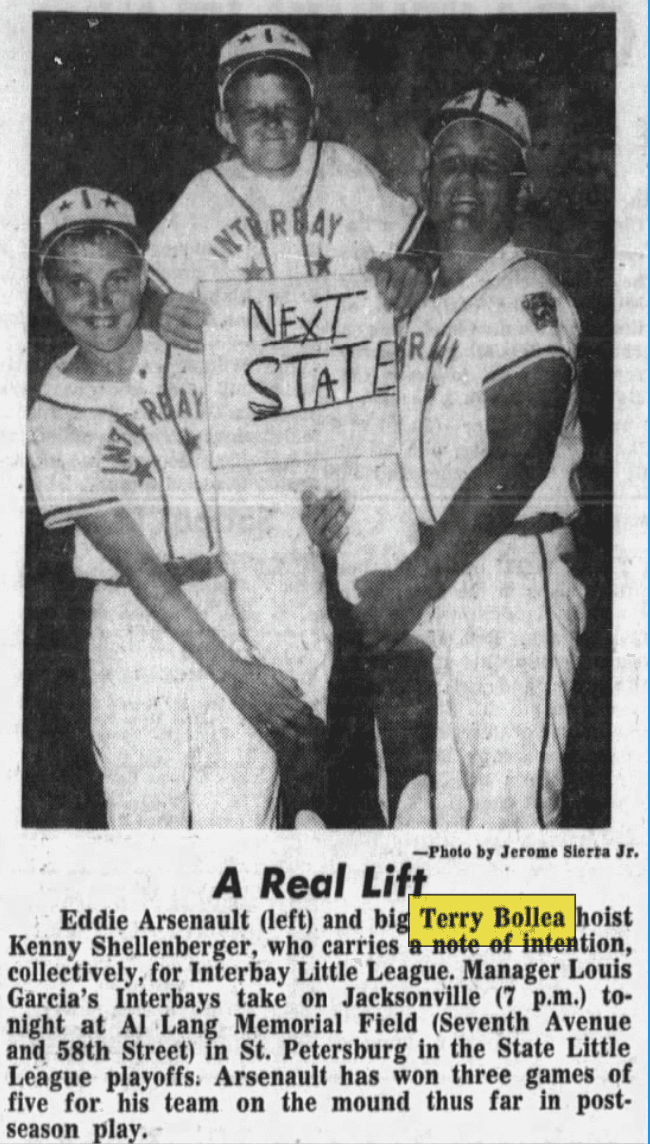

Music and bowling had taken precedence over physical sports like football or baseball in young Terry’s life. That isn’t to say he didn’t show flashes of athletic brilliance. Clearly much taller and stronger than most of his peers, Bollea offered dazzling performances on the baseball diamond when he wasn’t busy leading the bantam division of his local bowling league. A Tampa Tribune excerpt from May 1966 described how the 12-year-old Bollea fanned 15 batters from the pitching mound while allowing only one hit, then stepped into the batter’s box and supplied his team with its only two hits in a 2-0 victory. Photos from his youth show him towering over teammates, a physical anomaly even then.

His transformation began in Tampa’s music scene in the early 1970s. Playing bass guitar in local rock bands—first with Infinity’s End, then Magic, and finally the popular regional act Ruckus—Bollea developed the showmanship that would later electrify wrestling audiences worldwide.

Steve Keirn, a fellow Tampa native who was already wrestling in Florida and would later work alongside Hogan in the WWF as Skinner, recalled in his autobiography how he saw the mammoth Bollea in the crowd at one of his early wrestling matches: “I looked out into the audience during one of my earliest bouts and saw a tall, muscular, long-haired blond guy sitting in the crowd with his bare arms exposed. I immediately recognized him as Terry Bollea. He and I attended the same junior high and high school, except he was two years younger than me.”

After seeing Keirn wrestle a few times, Bollea approached him on the beach one weekend with a life-changing question. “Hey Steve! How do you get into wrestling?” Terry asked. Keirn tried to discourage him: “Man, I don't know,” I told him. “By the way, you don’t want to do this; I only make 40 bucks a night and have to pay for my own gas! You’re a bass guitar player in a band. Stay in the band! There’s no money in this! ... I would eventually live to eat those words.”

Asked to reflect on that moment after Hogan’s passing, Keirn said: “I didn’t have the power to give him that opportunity, but I didn’t want to tell him straight up that [the promoters] weren’t going to accept any advice from me or listen to my referral. It was the sort of thing that you had to do on your own, and make the right friends that could get you invited, and at the time, I wasn’t the guy who could do that for him. They would also physically abuse guys who were breaking into the business back then, and you had to be able to accept whatever they handed you and stick with it. In our case, that usually meant you got beaten up for six months before they actually taught you anything about the wrestling business.”

But Hogan was persistent and persistently in the public eye in one of America’s top markets for wrestling, so it was only a matter of time before someone else was willing to do what Keirn wouldn’t. Performing in clubs throughout Florida until 3 a.m., the 6-foot-7 musician with the tape-measure biceps caught the attention of veteran professional wrestlers Jack and Gerald Brisco at the Other Place nightclub in 1976. When former NWA World’s Heavyweight Champion Jack asked whether he’d ever considered wrestling, Bollea’s response was immediate: “It’s what I’ve always wanted to do.”

Brian Blair, a veteran wrestling star as one half of the Killer Bees in the WWF, and who would become Hogan’s first professional opponent and lifelong friend, recalled those early days: “My friendship with Terry started almost 50 years ago, when I was just 17 years old and sneaking into the Other Place lounge—also known as ‘The OP’—to watch him play bass guitar while he wore his huge platform shoes and his mother’s jewelry. Terry liked to heckle the wrestling heels in the Armory in Tampa back when the two of us were just fans, while I would just sit there and take it all in.”

The path to wrestling stardom proved difficult, and Hogan, who would later gain a degree of infamy for accidentally choking out Richard Belzer after Belzer. provoked him television host Richard Belzer, was old enough to be schooled in some genuine shooting techniques. Training under the legendary Hiro Matsuda in the tough Tampa gym known as “the Snake Pit,” Bollea experienced the sport’s harsh initiation when Matsuda deliberately injured his leg on the first day of training. Ten weeks later, with his injury healed, Bollea returned and earned the trainer’s respect. After more than a year of grueling preparation, he debuted on August 10, 1977, at Fort Myers’ National Guard Armory, defeating Blair as Terry “The Super Destroyer” Bollea.

“The first matches Terry had were against me in Chiefland and Fort Myers, Florida,” Blair remembered, “with the Brisco Brothers playing a legendary rib on the two of us during our Chiefland match to see how well two rookies could react to a sudden change in the program.” This change was intended to test the young wrestlers’ resolve: The Briscos lengthened the time limit without telling Hogan and Blair, who worked toward a furious finish and exhausted themselves, only for the ring announcer to get on the mic and announced there were 10 minutes remaining in the match. They were forced to improvise.

The territorial wrestling system of the late 1970s led a post-Florida Hogan to transform from the Super Destroyer to Sterling Golden to Terry “The Hulk” Boulder, and go from earning $200 a week with his friend Ed “Brutus Beefcake” Leslie in Alabama to being offered $800 per week to wrestle in Memphis by Jerry Jarrett. As he worked these territories, Bollea thought about the masters he'd grown up watching and who he'd ultimately model his persona on. In his book My Life Outside the Ring, Hogan writes that Saturday mornings in Tampa revolved around one man: “Dusty Rhodes was the be-all end-all. He beat everybody up ... the man of the hour, man of the power, the man too sweet to beat!” Watching Rhodes lace his curly white hair with blood and then rise for the comeback—“He’d get up and make the crowd explode with that Bionic Elbow, boom! Boom! Boom! Boom!” —etched the rhythm of a match into young Terry's mind: suffer, sell, fire up, finish.

Hogan also acknowledged the obvious debt he owed to “Superstar” Billy Graham, the former teenage bodybuilding evangelist who had done more than anyone to introduce the word “brother” into the wrestling lexicon (and steroids into the wrestling locker room). The first time the teenaged Terry Bollea saw Graham flex from a turnbuckle on Florida Championship Wrestling, he felt “like this golden god” had dropped from the heavens. “I want to be just like that guy someday,” he told himself, mesmerized by the bowling-ball arms and tie-dye regalia. Years later, when Bollea started working the Northeast, he even discovered that fans briefly mistook him for a younger, leaner Superstar. Vince McMahon Sr. noticed the confusion and quipped, “It’s like starting over with a brand-new Superstar Billy Graham,” foreshadowing Hogan’s billion-dollar value for Vince Jr. as the sport’s future superstar.

One night in a Cocoa Beach club, the awestruck bass player cornered his idol for bodybuilding secrets: “Hey, man, you know anything about steroids? You ever taken steroids?” Graham flashed a knowing smile and waved him off—“No, brother. Never taken ’em.” Hogan writes that he accepted the answer in the moment, even though history would brand Graham one of wrestling’s steroid pioneers. “He certainly wasn’t gonna admit it to this nobody bass player,” confessing that Graham’s coy denial only deepened his own curiosity about the chemical edge behind those impossible biceps.

Hogan’s first taste of national exposure came during an initial WWF stint from 1979 to 1981, when he worked as a heel and famously body-slammed Andre the Giant (one of several to have done so during this period) at Showdown at Shea—seven years before their WrestleMania 3 encounter. When Sylvester Stallone personally called to offer Bollea the role of Thunderlips in Rocky III, it led to his WWF firing—Vince Sr. told him it was wrestling or Hollywood—but launched his mainstream crossover. Moving to Verne Gagne’s AWA in Minneapolis from 1981 to 1983, Hogan’s popularity exploded. He began selling “Hulkamania” T-shirts from his car trunk, making progressively more and more from merchandise alone.

The Minneapolis Star Tribune from October 1983 reveals the sudden nature of his departure from Gagne’s territory: Intending to settle down, Hogan purchased a house at 9357 Nesbitt Road for $125,000, only to sell it at a $6,000 loss less than a year later. WWF’s Vince McMahon Jr., who had long wanted the company he had just acquired from his father to have a champion in the Billy Graham mold and knew that the Hulkster fit the bill, came calling with an offer that Hogan clearly couldn’t refuse.

January 23, 1984, at Madison Square Garden became wrestling’s equivalent of the moon landing. Before 26,292 fans, Hogan defeated the Iron Sheik to win his first WWF Championship. The 1,474-day title reign that followed coincided with wrestling’s explosion into mainstream entertainment. Saturday-morning cartoons, action figures, and Hogan’s starring role at the inaugural WrestleMania transformed professional wrestling from regional curiosity to global phenomenon.

The transformation began almost immediately with Hogan’s integration into MTV’s programming, a revolutionary crossover for professional wrestling. His appearances on the network throughout 1984 and 1985 introduced wrestling to MTV’s young, trendsetting audience, through his participation in “The Brawl to End It All” and “The War to Settle the Score.” The latter special, which featured Hogan defending his title against Roddy Piper with celebrity appearances by Cyndi Lauper and Captain Lou Albano (whose own real-life friendship and story line feud had prompted “The Brawl to End It All”), demonstrated wrestling’s newfound mainstream appeal and set the stage for an even more ambitious project.

Vince McMahon’s strategy to elevate wrestling through celebrity associations found its perfect vehicle in Mr. T, whose popularity from The A-Team made him one of television’s biggest stars. Hogan’s November 1985 appearance on the hit NBC series saw him playing himself alongside Mr. T’s B.A. Baracus character, further cementing wrestling’s place in popular culture. The partnership between Hogan and Mr. T became the cornerstone of WrestleMania’s marketing campaign, with their tag team main event against Piper and Paul Orndorff drawing mainstream media coverage unprecedented for professional wrestling. Muhammad Ali as special referee and Liberace as guest timekeeper transformed what could have been dismissed as a wrestling show into a celebrity spectacle that drew attention from outlets as varied as Entertainment Tonight and The New York Times—but it was Hogan’s in-ring savvy that helped him carry the novice Mr. T to a halfway decent match against veterans Piper and Orndorff. None of it could’ve worked without Hogan as the glue.

The success of this formula—combining Hogan’s charisma and ability to work a psychologically compelling wrestling match against anyone with mainstream celebrity involvement and savvy marketing—established the template for wrestling’s expansion. He implored his fans to “say your prayers and eat your vitamins,” and the masses fell in line. By the time of WrestleMania III, the WWF had perfected this approach, with Hogan at the center of a merchandising empire that included everything from foam fingers to vitamins. The WWF’s first great wave of popularity crested that March day in 1987, when Hogan became the first man to body-slam the 520-pound Andre the Giant before a claimed 93,173 fans—actually closer to 78,000, but who’s counting—at the Pontiac Silverdome. That moment crystallized Hogan as an American hero incarnate, though the image obscured a more complex reality.

Steve Keirn, despite their shared Tampa roots, was working as a main-event star in various regional territories and maintained a careful distance from Hogan during his superstar years: “I could pick up the phone and talk to him, but I wasn’t as close to him as a best friend is. I always made a joke that we didn’t hang out because it was like hanging out with Elvis. I didn’t want to stand by his side because I knew I’d be shoved around. I waited for him to come to me if he wanted to say something. It was just a different circumstance being in public with him. Other people were always trying to get next to him and conduct business with him. He had a lot of people who would say that he was their best friend, but they were usually the ones he was giving money or opportunities to. I doubt he thought of them the same way.”

That superhero-like presence and swagger were owed in part to chemistry. Hogan, who once had bugged Billy Graham for his steroid secrets, fused hard-core gym sessions with pharmaceutical drugs to achieve his signature 24-inch pythons. In My Life Outside the Ring, he recalled 1978, when Cocoa Beach lifters pitched steroids “like traveling salesmen” at Whitey and Terry’s Olympic Gym (which he co-owned—he was always chasing business opportunities). “Brutus [Beefcake, Ed Leslie] and I were sold, right then and there, and when we got into it, we got into it heavy,” he wrote. His routine was simple: testosterone base twice weekly, plus Deca Durabolin injections and daily Anavar and Dianabol tablets. A friendly doctor kept prescriptions flowing so the stash looked “street legal.”

“In just a couple of months I was seeing that sort of Greek god swell I envisioned,” he admitted, still half-marveling at his reflection decades later. The Hulkster insisted the brew never turned him into the monster the tabloids imagined. “I’ve been around more steroid users than the average person, and ’roid rage is something I have never, ever seen,” he wrote, calling the idea “some sort of an urban myth.” The real side effects were pro-wrestling pedestrian: constant sweat, “killer acne,” and ingrown hairs on a neck thick enough to hide them during promos. He writes that he quit using steroids in 1992: “It just wasn’t worth it anymore.” In his 1994 testimony in Vince McMahon’s federal steroid trial, Hogan admitted to 13 years of use while helping acquit his former boss (a far cry from the single use to which he publicly admitted on an unfortunate episode of The Arsenio Hall Show, one of many instances of Hogan stretching the truth).

Lost in his American superhero rise-and-fall narrative was Hogan’s remarkable success in Japan, where he shed his simplistic ring style for an approach that showed off his technical excellence. Hogan was an instant sensation in 1980 in Japan, where wrestlers with his specific combination of youth, size, and muscularity were unprecedented. In only his second visit to Japan, he was positioned as a challenger to the National Wrestling Federation heavyweight championship belt of Antonio Inoki, the incumbent ace and owner of New Japan Pro-Wrestling, and soon chased longtime Inoki foil Tiger Jeet Singh for the position of top foreigner in the promotion.

Hogan wrestled in New Japan as a frequent partner of Stan “the Lariat” Hansen. While Hansen would come to be known in Japan primarily for the excellent quality of his ring work, much of his initial popularity was owed to his use of the western lariat as a signature maneuver. The straight-arm strike had become famous for its alleged role in breaking the neck of longtime WWF heavyweight champion Bruno Sammartino (a breakage actually caused by an errant body slam).

When All Japan Pro Wrestling successfully poached Hansen away from New Japan Pro-Wrestling in retaliation for Inoki’s theft of Baba’s eternal foreign adversary Abdullah the Butcher, Hogan quickly adopted his own version of Hansen’s lariat—a bent-elbow version called the “Axe Bomber”—as his finishing maneuver. This was one of a confluence of events that overlapped with the success of the Rocky III film, the ripples of which spilled over into Japan.

In short order, Hogan became a foreign babyface in Japan, and often partnered with Inoki against combinations of Japanese and American opponents. Then, in the finals of the 1983 International Wrestling Grand Prix League tournament, Hogan delivered one of the most memorable blows in the history of puroresu, when he unleashed an Axe Bomber lariat on a dazed Antonio Inoki and sent him crashing to the ringside floor. Inoki was counted out as the cameras hovered over him and captured his tongue hanging out of his mouth. Hogan was then presented with the IWGP championship belt, making him the first official wearer of the same belt with the iconic circular center plate that would ultimately serve as the New Japan heavyweight championship belt from 1987 until 1997.

Although pro wrestling norms would suggest that Hogan owed Inoki a clear-cut victory in a rematch with IWGP supremacy on the line, such a bout would never come to pass. Owing to Hogan’s protected status as the WWF World Heavyweight Champion, he would only lose to Inoki in the 1985 League Finals by countout during the summer of 1985, in an unsatisfying ending that was a harbinger of the inevitable dissolution of the WWF-NJPW partnership in October 1985.

Brian Blair, who worked in Japan himself, noted: “I always called Terry ‘Ichiban,’ which means no. 1 in Japanese. The reason for this was because he was big in Japan—both literally and figuratively—and that’s what the Japanese fans called him.”

Throughout his later years as WWF heavyweight champion, Hogan became the frequent target of criticism that he would only work in a soft, formulaic style that was incompatible with the style of workrate darlings like Ted DiBiase, Bret Hart, and Randy Savage. If nothing else, Hogan’s match with his former Japanese tag partner, Stan Hansen, at the Wrestling Summit in 1990 showed that Hogan’s perceived indolence in major matches was a choice rather than an inherent physical limitation.

Facing All Japan’s foreign ace, Hogan gave as good as he got for 12 minutes before securing victory with his Axe Bomber. When Hansen finished 1990 as the rightful holder of All Japan’s own version of the world heavyweight championship, known as the Triple Crown—consisting of three storied championship belts and the NTV cup trophy bearing the engraving “world heavyweight champion”—the eyeball test showed Japanese fans that Hogan remained stronger than AJPW’s top competitor.

In May 1993, Hogan made his first New Japan appearance in eight years, defeating IWGP Champion Great Muta. His post-match comments to the Japanese press were revealing of just how highly he esteemed puroresu: “This [belt] is just a toy,” he said of the WWF title. “It’s like a trinket on a Christmas tree. … The belt that I want is the one that the Great Muta has: the IWGP belt. Because when Hulk Hogan wins the IWGP championship—which he should have right now—it will prove that New Japan Pro-Wrestling and Hulk Hogan are the greatest partners in the world, because I want all the great wrestlers to come to me, and I want them to come to Japan where I can wrestle and not bullshit.”

Setting aside for a moment that Hogan may have been making a good-faith effort to appeal to his Japanese hosts with a blunt claim that their championship was of a superior vintage to his own, Hogan’s statement also betrays what may have been the resentful acknowledgement that his relaxed style of wrestling in the U.S. had not earned him plaudits in Japan. Certainly, ever since his match with Hansen at the Wrestling Summit, Hogan’s bouts in Japan were laced with an uptick in effort. This included cross-armbreaker takedowns, repeated enzuigiris, and grappling exchanges that were often won by Hogan via his energetic, good-faith attempts at pulling off the spinning headlock-hammerlock-leglock takedown popularized by the original Tiger Mask. Unlike more limited, fast-talking muscle wrestlers like Billy Graham and Jesse Ventura, who smartly did as little as possible to get over, when put to the test, the Hulkster could both work and draw.

Hogan’s lengthy domestic championship reigns required a rotating cast of challengers, with WWF’s booking following distinct patterns, such as Hogan being beaten up and expressively selling his pain for most of the match until “hulking up” at the end to overcome seemingly impossible odds (sometimes doing so with back rakes and eye rakes, marking him as one of the few good guys who used bad-guy offense as part of his regular repertoire). The company regularly positioned massive heels as physical threats who could credibly endanger the champion. King Kong Bundy’s avalanche assault leading to WrestleMania 2 established the template: a brutal attack requiring Hogan to overcome seemingly insurmountable odds. This formula was probably best deployed in ring with Earthquake (John Tenta), whose 1990 program with Hogan drew exceptional television ratings and house show attendance. Tenta’s legitimate 450-pound sumo frame and surprising agility made their matches compelling beyond the typical giant encounters, with their SummerSlam 1990 bout showcasing such genuine chemistry that Tenta was later brought into WCW years later to try to rekindle that magic.

The most emotionally resonant feuds emerged from betrayed friendships, a storytelling device that allowed Hogan to display vulnerability beyond physical peril. Paul Orndorff’s 1986 heel turn, triggered by perceived slights during their partnership, created genuine heat and drew massive crowds, including a reported 61,000-plus for their CNE Stadium encounter in Toronto (with some sources claiming over 70,000). The Mega Powers explosion between Hogan and Randy Savage over Miss Elizabeth produced wrestling’s smartest story line of a 1989 wrestling calendar filled with amazing in-ring action, culminating at WrestleMania 5 in a match that balanced technical wrestling with soap-opera drama.

The Ultimate Warrior presented a unique challenge as neither monster heel nor former friend, but rather a hugely-muscled babyface whose popularity approached Hogan's own and whose physique, albeit on a shorter frame, exceeded his. Their WrestleMania 6 encounter, marketed as “the Ultimate Challenge,” saw Hogan cleanly lose the WWF Championship for the first time in more than six years. The match itself exceeded expectations, with both men working at an intensity level that produced what many consider the best bout of the Warrior’s career and another example of how Hogan could manage the pacing of a match. Even Sgt. Slaughter’s controversial 1991 Iraqi sympathizer character, despite its problematic nature, generated significant business when pitted against Hogan during the Gulf War period, with their WrestleMania 7 match requiring a venue change allegedly due to security concerns (though poor ticket sales was the more likely reason). Their subsequent, feud-ending “Desert Storm Match” at Madison Square Garden was a hidden gem).

These feuds established Hogan’s ability to elevate opponents while maintaining his status as the company's centerpiece. Whether facing monsters, former allies, or fellow heroes, the Hogan formula consistently drew money even as critical opinion varied on match quality. Mike Rotunda, one of only three living Hogan opponents from the first nine WrestleManias (he wrestled, and defeated, Hogan and Brutus Beefcake as part of Money Inc. at WrestleMania 9), offered his perspective on that incredible drawing power: “I respected Hulk. I was on a lot of his shows. He said that he got the Hulk Hogan character over so well that he didn’t even need an opponent at WrestleMania to draw money. I didn’t necessarily agree with that. You couldn’t just have Hogan put on a 10-minute main event without anyone supporting him. With that being said, easily the biggest payoff I ever had was wrestling Hogan at WrestleMania 9. I wish I’d had six months wrestling Hogan every night. It would have been huge money for me as a heel.”

In the early 1990s, Hogan attempted to recapture the magic of Rocky III, but his starring roles in movies like No Holds Barred and Suburban Commando were widely panned. He retired from the WWF and promised Vince McMahon he’d never work anywhere else in the ring. But when WCW offered a lucrative deal in 1994, Hogan headed south and spent several years rehashing his greatest hits, wrestling old foes as well as a stable of giants, headed by Kevin Sullivan, to mixed fan reactions. The solution to that lukewarm reception came at Bash at the Beach 1996, when Hogan shocked 8,300 fans by turning heel and joining the New World Order. The nWo’s black-and-white merchandise became ubiquitous, their rebellious cool attracting audiences who’d outgrown Hulkamania’s simplicity, and Hogan, as ripped as he'd ever been and sporting a black beard, proceeded to have a great heel program with Sting while running down most of the company’s good guys.

The nWo angle powered WCW to nearly two years of ratings success in its “Monday Night War” against WWF, with Hollywood Hogan’s heel persona generating significant heat and revenue. The turn created fresh story lines even as Hogan revisited many past rivalries. His extended feud with Sting, truly the most novel and best of these story lines, became WCW's most anticipated program—the crow-faced vigilante stalking the nWo from the rafters for more than a year, building to their Starrcade 1997 main event. However, the match became controversial when referee Nick Patrick’s count appeared normal rather than the planned “fast count,” creating confusion about the finish that required clarification on the following night’s Nitro.

Between main event programs, Hogan faced several of his classic opponents (though they were often diminished by wear, time, and an unwillingness to lose cleanly to Hogan, and vice versa) in new contexts. His matches with Randy Savage featured extensive interference and story line complications that distinguished them from their earlier, tighter WWF encounters. His feud with Roddy Piper included cage matches that showcased both men’s veteran psychology, despite their physical limitations. Perhaps most infamously, Halloween Havoc 1998’s rematch with the temperamental Warrior incorporated hokey supernatural elements including smoke effects, trap doors, and Warrior appearing in mirrors—a silly but still sharp departure from traditional wrestling presentation that prefigured WWE’s “Firefly Fun House” match presentation by two decades.

Two title changes marked significant shifts in WCW’s landscape. On August 4, 1997, Lex Luger—who had previously been positioned as Hogan’s potential successor in WWF, only to have his hopes dashed—defeated him cleanly for the WCW World Championship on Monday Nitro, a victory that elevated Luger to genuine main-event status. The even more definitive transition came at the Georgia Dome on July 6, 1998, when former NFL player Bill Goldberg—whose retirement match came the same month as Hogan’s passing—carrying an undefeated streak, defeated Hollywood Hogan in front of 41,412 fans with his signature spear and jackhammer combination, both ending a title reign and effectively closing the nWo’s period of dominance.

As WCW faced increasing competition from WWF “Attitude Era” stars like Steve Austin and the Rock, Hogan’s role evolved. He was not part of WWE’s initial 2001 purchase of WCW, but returned in 2002 for a highly anticipated match with the Rock at WrestleMania X8. The Toronto crowd’s response organically shifted Hogan to a fan favorite during the match—his own keen instincts for psychology didn’t hurt—leading to another WWE Championship reign and a run as the masked Mr. America character. This stint included matches with emerging stars like Brock Lesnar and Shelton Benjamin, the latter of whom is still active in AEW, before ending with another departure from the company and breakup with McMahon in 2003. His subsequent appearances in both WWE and TNA saw him primarily in leadership and special attraction roles rather than as a full-time competitor.

After his retirement from full-time in-ring wrestling, Hogan did show his ability to move with the American zeitgeist by embracing reality television. Hogan Knows Best premiered on VH1 in 2005, presenting Hogan’s family as successful but relatable, with his obsessiveness regarding aspiring singer/actress daughter Brooke’s personal life providing many of the most memorable story lines. The show collapsed amid a slew of family crises: alleged affairs, divorce proceedings, and a serious car crash involving his son. The television family’s disintegration presaged the collapse of his public image.

Brooke’s love life figured into the greatest scandal of Hogan's life. The scandal began when Gawker Media released sexually explicit footage of Hogan and Heather Clem, the wife of Hogan's friend, radio personality Bubba the Love Sponge. Hogan immediately filed a $100 million invasion of privacy lawsuit against Gawker. During the legal proceedings, sealed court documents revealed the existence of additional recordings, including a recording that contained clear audio of Hogan expressing racist views. The transcript, which emerged in 2015 when the National Enquirer reported on the sealed deposition, included Hogan saying: “I’m not a double standard type of guy. I’m a racist, to a point, y’know, fucking n------.” It was Hogan's comments, not the sex tape or the subsequent lawsuit against Gawker, that led to WWE immediately terminating his contract and removing him from its Hall of Fame.

In the aftermath, wrestlers and sports figures rushed to defend him. Mike “Virgil” Jones stated the wrestling icon “had been his role model, and being white, he never showed any signs of racism,” according to TMZ. George Foreman said he’d “known Hogan for over 20 years” and was certain he wasn’t racist. Kevin Nash tweeted his support: “I’ve spent the last 23 years of my life with Hulk. I’ve been in the most diverse of situations and never heard Hulk use a racial slur.”

Maybe these defenders presumed that wrestling’s ultimate locker room politician would have revealed his true feelings if he’d held any. Maybe they underestimated the extent to which wrestling veterans can work everyone when something is to be gained or lost. The fact remained that an entire generation of wrestling success had been built on Hogan’s legacy. Too many dreams fueled by Hulkamania had reached maturity for the industry to reconcile Hogan's hero image with his admitted racism. The subsequent lawsuit against Gawker, secretly funded by billionaire Peter Thiel, resulted in a $140 million judgment (later settled for $31 million) that bankrupted the media company. The victory victory led many critics to raise justifiable questions about press freedom and oligarch overreach even as the payment restored Hogan’s bank account after his divorce and after numerous business ventures—Hulk Hogan’s Pastamania, the Hulk Hogan Thunder Mixer, and the Hulk Hogan Ultimate Grill (his attempt to dethrone George Foreman in the countertop appliance wars, and since recalled for safety reasons)—that had gone south (the fate of Real American Beer, his latest such venture, remains uncertain).

His political evolution from Obama supporter in 2008 to featured speaker at Trump’s 2024 Republican National Convention reflected broader American polarization. Ripping off his shirt to reveal a Trump-Vance campaign shirt while declaring them “the greatest tag team of my life,” Hogan’s final major public appearance—and last noteworthy wrestling-style promo—cemented his transformation from all-American hero to partisan figure.

Behind the controversial character lay a broken body and a fractured family. Numerous surgeries in his final decade left the still-hulking Hogan dependent on a cane and unable to feel his legs. He had personal struggles, too: In 2009, his first wife, Linda, received 70 percent of their liquid assets in their divorce, while car-obsessed son Nick’s reckless driving incident left friend John Graziano in a vegetative state.

Through their shared personal struggles, Brian Blair remained loyal: “Even when our oldest son Brett was killed, Terry was there for me. Even though his back was hurting so bad and the COVID-19 pandemic was rampant, Terry came to Brett’s memorial service. He was always doing his best to cheer me up even though he was dealing with his own challenges.”

Blair recalled Hogan’s support during his own health crisis: “Terry called me almost every day that I was in the hospital with crippling osteomyelitis. I was in dire need of a good surgeon, so Terry called three different doctors for me before I wound up with the best spinal surgeon in the world.”

Steve Keirn observed a profound spiritual transformation in Hogan in his final years: “He had a different attitude after he started saying he was a Christian. When Bubba the Love Sponge was saying unkind things about him in the press [related to the sex tape], I went to Hogan and said, ‘You must hate that guy.’ He said, ‘Nah. If I don’t forgive him, how is God gonna forgive me.’ It wasn’t like he suddenly had a halo over his head. He was at peace, and nothing people said about him seemed to matter to him anymore like it used to. He knew with all of his medical issues, there was going to be a time when he was going. He wanted to be at peace with God and Jesus when that time came.”

Keirn also reflected on how Hogan’s understanding of his own success evolved as he neared his end: “As big of a character as he was worldwide, he had to feel like he was invincible, and I’m sure he put God on the backburner because he was trying to make people like him as opposed to dislike him. He was trying to make people like him that he shouldn’t have been doing. All of that seemed to go away in his later years. He lost his instinct to think he was a hero or a god himself.”

Whether remembered as a best friend or a hated villain, Hulk Hogan was undeniably wrestling’s first true crossover megastar, the next form of evolution from Billy Graham’s “superstar” and capable of establishing the template that subsequent breakout performers such as Dwayne “the Rock” Johnson and John Cena would follow. His success proved wrestling could transcend regional boundaries and demographic limitations. The formula—superhuman physique, memorable catchphrases, clear moral positioning, mainstream media appearances—seems obvious only because Hogan learned from the masters and perfected it first.

His death prompted immediate tributes from across the cultural spectrum. WWE called him the most recognized wrestling star worldwide, which is likely true. President Trump praised him as being “strong, tough, smart, but with the biggest heart.” Wrestling colleagues acknowledged his industry-defining impact, transforming professional wrestling from niche entertainment into a billion-dollar business. Given his many controversies, the sport may not have lost its favorite son, but it certainly lost its most famous one.