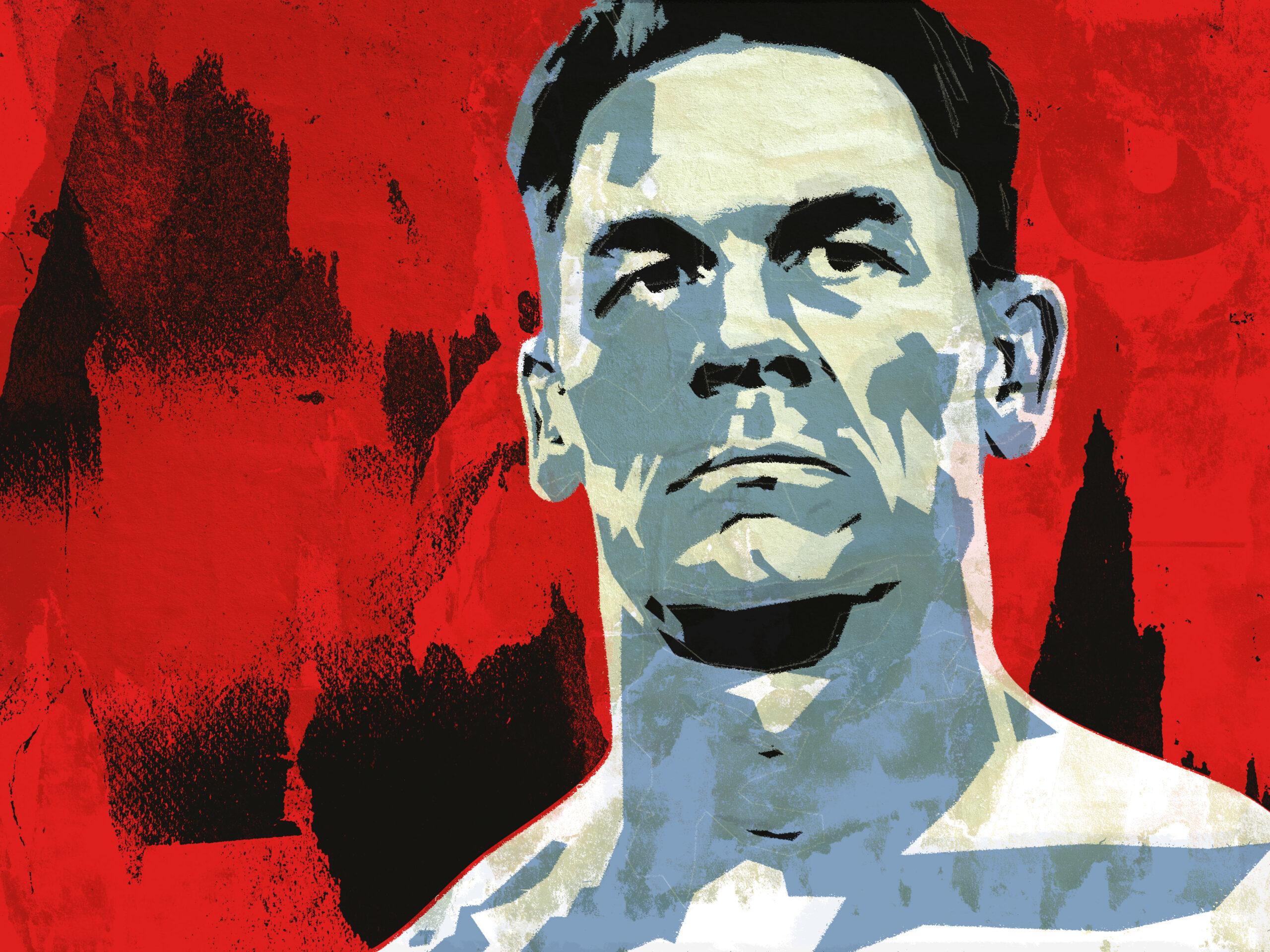

On the October 10, 2002, episode of SmackDown, a young up-and-comer named John Cena was teaming with Billy Kidman against the uneasy alliance duo of Kurt Angle and Chris Benoit in a tournament to crown the inaugural WWE Tag Team champions. Cena was the kind of prospect you could look at and imagine whatever future you wanted for him. Superstar. Future world champion. WrestleMania main eventer. To imagine the heights he actually reached would have been near sacrilegious, but the point stands. With his superhero physique, his impressive athleticism, an eager vocabulary of moves, and a palpable ambition to his whole presence, John Cena had all the tools. At this point, he was a blank slate—in both the best and worst ways simultaneously. He was an avatar for pro wrestling potential. If there was any knock on Cena then, it was the logline that came prepackaged with him: Hey, look at this guy. He’s pretty cool, right? Right?

He and Kidman would lose that match, but it was still an impressive outing. Whether he was being carried along by his veteran opponents (and his veteran partner) is beside the point—he had the tools to not look out of place with them in the ring. When Kidman tapped out to end it, you could see Cena in the background, outside the ring, grabbing his head in disappointment. That, more than anything he proved in the ring that night, would foretell his future: It was the kind of oversized, cartoonish behavior a megastar career could be built on.

By the following week, Cena had done a 180 on his clean-cut demeanor. “Just for the record, last week when Billy Kidman and I lost to Kurt Angle and Chris Benoit, you know who tapped out to lose that match? Billy Kidman,” he said. “Not me. Billy Kidman better get used to losing.” He delivered those lines with a believable smirk on his face, though even at his most lovable, Cena has always had the kind of face you love to see smacked. “A different side of John Cena, and I like it,” said color commentator Taz as Cena entered the ring to wrestle Kidman. He embraced the heelish ring style: less flash, more reluctant to exchange, more salty in his reactions. At one point, he slung Kidman into the corner with such force that Kidman hit the turnbuckles chest-first and collapsed to the mat, and Cena just mugged at the crowd joylessly, rage bubbling out through his pores. From there, it was mostly a squash match—Kidman had a few hope spots, but the story was Cena dominating his smaller ex-partner with power moves and a new attitude. The crowd, at one point, erupted into a foreboding “Cena sucks” chant. It was a harbinger of things to come, and the announce team made note of the moment. Kidman rallied at the end, but Cena pulled out a win with a crucifix roll-up. In case you weren’t sure you were watching a heel, Cena put his feet on the ropes for illegal leverage during the pin. There’s no more poignant indicator of heeldom than that. On the way up the ramp, he glowered incredulously at the fans, as if he didn’t understand why he was getting booed—another omen.

Shortly thereafter, Cena dressed as Vanilla Ice on the SmackDown Halloween episode and accidentally launched a new persona as a white, Boston-bred rapper: the Doctor of Thuganomics. Needless to say, this was Iron Sheik–level detestability. There was no more confusion on his face. Cena had created an entirely self-possessed villain. But there was just too much joy in his deviousness, too much electric possibility in his angst. He had gone from a blank slate to an undeniable persona. And like some of the best heels, he was too likable to be a bad guy for long.

Cena was a fan favorite by Survivor Series that November, and he would remain so for the next 21 years. For probably 15 of those years, through much of his time as the top wrestler in the company up through his semi-retirement in 2019, fans begged for a Cena heel turn.

The reasons are myriad. Post-Thuganomics, Cena morphed from a rapper on the come-up into a sort of hip-hop mogul, but rather than take an office job, he was still tossing guys in the ring; it was the same routine without the street cred. He was built in the mold of Attitude Era heroes like the Rock, but this wasn’t the Attitude Era—this was a newly chaste era in which WWE was chasing a TV-PG rating to appeal to younger fans, and so Cena reigned over a period that didn’t carry the same vitality. Moreover, Cena seemed at times to be the only real star of WWE’s PG era, or the only one that the WWE brass consistently cared about, and there was an inherent monotony in that. So were his story lines. The vibes were Attitude Era, but the booking was straight out of Hulkamania, where good versus evil was less an archetype than a mission statement. “Super Cena” became an online term of derision—his comebacks “against all odds” were so predictable that the routine belied the stories WWE was trying in earnest to tell.

Moreover, many fans despised the product—both because of the limitations of PG television and the overall malaise of a company whose storytelling seemed to be built on insulting its audience. And Cena was the star, the avatar of an empty era. Just as Cena’s popularity grew, resentment toward what he represented enveloped it. Soon, every Cena appearance was greeted with competing chants: “Let’s go, Cena!” / “Cena sucks!” During his absolute peak, nobody got bigger boos than the hero of the company.

There were moments when a heel turn seemed imminent. There was the weird story line in which Cena was a terrible friend to Zack Ryder, who was beloved by fans and stuck in a wheelchair. Or that night on Raw when Rey Mysterio started the night winning the WWE Championship … only for Cena to take it from him in the last match of that show. There was one time when Cena got into the ring and did a literal heel turn—a little dance step—to play with the crowd. Cena almost turned heel in 2012 during his feud with the Rock, but plans changed. Momentum—or malaise—won out. When Cena announced his retirement tour last year, it seemed inevitable that it would go the way of most last tours—he would go out playing the hits to nostalgic fans.

But on Saturday night, in front of 38,000 fans at the Rogers Centre in Toronto for WWE’s Elimination Chamber PLE, Cena finally did it. He finally turned heel. The mechanics matter, but they exist in the shadow of the turn. Cena won the six-man Elimination Chamber match, the winner of which gets to face WWE Universal champion Cody Rhodes at WrestleMania in April. Cena was met in the ring by Rhodes, where the two nominal babyfaces shook hands. Then came the Rock, the pro wrestling icon who also holds a position on the board of parent company TKO and these days flaunts his front office power as a bad guy on-screen as “the Final Boss.” Over the past couple of weeks, he’s been haranguing Rhodes to give him his “soul”—i.e., to sign a deal with the devil and become the Rock’s corporate champion. On Saturday, Rhodes declined. (“Go fuck yourself” were his exact words.) In the background, in the oversized gestures that make Cena so memorable and grating, Cena cheered on Rhodes’s insolence. He hugged Rhodes, but when the Rock made the throat-cut signal, Cena’s face went blank. It echoed his expression from the Kidman match all those years before, but this was even darker, even more diabolical. He assaulted Rhodes, and the Rock joined in. (As did Travis Scott, who was inexplicably there with the Rock.)

Presumably, Cena will have to explain himself, though he’s not scheduled to appear on Raw or SmackDown for the next two weeks. It doesn’t matter—he’ll be there in April at WrestleMania squaring off against Rhodes, a huge event at a huge moment in time for WWE. The company is as hot as it’s ever been in so many ways, but the WrestleMania card was severely lacking in the kind of hype baked into the last two WrestleManias, with Rhodes trying to dethrone champion Roman Reigns. At the press conference after the Royal Rumble in February, Cena said him main-eventing at ’Mania would be best for business. It was a sly hint at the turn to come, but also a statement of fact. WWE needed John Cena in that match. More specifically, it needed heel John Cena.

When Cena feuded with the Rock—himself a returning Hollywood star—at WrestleMania 28 and 29, WWE needed the Rock. But there’s a deeper connection here. The ex-wrestler returning for a WrestleMania match is a time-honored tradition, but more often than not, the returning luminaries are presented as heroes when functionally they’re playing heel—taking big-match spots from the wrestlers we’ve been rooting for week in and week out throughout the year. Usually this is subtext, but at WrestleMania 30, when Dave Bautista came back, the fans revolted against the notion, and underdog favorite Daniel Bryan (a.k.a. Bryan Danielson) got edited into the main event—and walked out as champion. Cena has his own history with Danielson. At SummerSlam in 2013, needing to take time off to repair a torn tricep, Cena dropped the WWE Championship to Danielson on his way out the door. It was a good-faith move by Cena, maybe the most truly heroic thing he’s ever done, to identify Danielson as the right guy to take the title from him, and yet as Cena stood across from Danielson in the ring, the “Cena sucks” chants were louder than ever. I used to say that even if Cena wasn’t your favorite wrestler, he was the guy your favorite wrestler stood next to in order to make them seem important. Now, he gets to be the guy your favorite wrestler beats the hell out of to get revenge.

In telling its own history, WWE often emphasizes its missteps as a way of controlling the narrative. One of the most famous examples is that of the Rock, who, at his debut, was known as Rocky Maivia. WWE pushed him as a clean-cut, all-American good guy, and he was so painfully boring that his career was almost lost before an injury took him out of action and the company decided to turn him heel on his return. That move truly helped redefine the company. But in looking at the nearly two decades of Cena’s career before Saturday, it feels like no lesson was learned. Instead of listening to the unrest of the crowd and going the Rock route, WWE doubled down on the Maivia. Finally, the heel turn has come, and it’s fitting that Rocky is Cena’s benefactor now. The Rock himself returned to action a year ago and almost fell into the same trap, until fan unrest forced him into playing the villain role. WWE seems to have learned its lesson this time—finally, Cena is following in the Rock’s footsteps.

There is a certain irony in Cena’s turn coming at a time when even the most jaded fans were willing to root for him because of all he’s given to the industry over the years. Even the “Cena sucks” contingent seemed on board for a rote valedictory tour. There was always an accidental genius to WWE’s reluctance to make Cena a heel—staying the course allowed him to be the company’s biggest hero and villain at the same time. When Cena talked about turning heel, he talked about doing a reversal on his core principles—hustle, loyalty, and respect—but the truth of the matter is that those cereal box paradigms were exactly what was so grating about him in the first place. His earnestness, his prepackaged heroism, is what made him so loathsome. Now, fans were grateful above all else. Or maybe they were just happy to wave him goodbye.

In the end, just like Hulk Hogan in 1996, and just like Andre the Giant in 1987, the only thing Cena could do to make the fans happy was to turn on them. It took him long enough.

Whether he wins at WrestleMania is another story. Fans will argue about whether he should win, when the match should go on, and how long the story should last. But despite all the uncertainty, one question will be at the forefront of every fan debate moving forward: When is WWE going to turn him face again?