In a winter when many MLB teams have been slow to shore up deficiencies, several front offices have reinforced areas of strength, stockpiling players at positions where they already seemed set.

The Mets acquired two of baseball’s best veteran second basemen, trading for Robinson Canó and signing Jed Lowrie, despite the presence of 23-year-old shortstop Amed Rosario and 26-year-old second baseman Jeff McNeil, who hit .329/.381/.471 (137 wRC+) with an impressively low strikeout rate in 63 games last season. The A’s traded for second baseman Jurickson Profar, effectively blocking 22-year-old Franklin Barreto, who managed a 100 wRC+ in 32 games last year (mostly at second) and just lit up the Venezuelan Winter League. The Padres signed Ian Kinsler, even though they boast the top prospects in baseball at second base (Luis Urias) and shortstop (Fernando Tatis Jr.). The Yankees signed shortstop Troy Tulowitzki and Gold Glove second baseman DJ LeMahieu, forcing Gleyber Torres to compete for playing time until the injured Didi Gregorius returns. The Braves signed Josh Donaldson, displacing their primary third baseman from 2018, Johan Camargo, who posted a 115 wRC+ and was worth 3-4 WAR.

With more than two months to go until Opening Day, there’s still time for trades to resolve positional logjams. In each of the cases above, though, the team with an apparent redundancy at a particular position isn’t acting as if it needs to deal anyone. Instead, it’s converting a player who’s historically been stationed at a single position into a roving, superutility type who can fill in all over. Baseball’s latest fad is the productive player who moonlights at many positions—not just by necessity, but by design. In the modern game, where balls in play (especially grounders) are relatively scarce, shifting is increasingly common, and pitching staffs are rapidly expanding, every club is coveting or creating a Ben Zobrist of its own, and what looks like a backlog is actually desired depth.

Consider the cases above. With the Mets, the 34-year-old Lowrie, who hasn’t played a position other than second or third since 2016, expressed a willingness to play all over the infield, saying, “If you look at a lot of teams that have had recent success, they’re very deep, and I think that’s what it takes to win at the major league level at this point.” McNeil, meanwhile, has played at least three games at six positions in the minors in preparation for a superutility role, and he’s slated for regular outfield duty in 2019.

Elsewhere in New York, LeMahieu—who’s played second exclusively for the past four seasons and ranked second at the position in defensive runs saved over that span—is expected to spend time at first and third. The 36-year-old Kinsler, who ranks first on that DRS leaderboard, has played only one major league game at a position other than second (at third base in 2012), but San Diego is grooming him for a utility role, and he’s planning to play some third in spring training. In Oakland, Barreto is in line for what A’s GM David Forst described as a “utility role” that will see the prospect play “a little bit everywhere.” And in Atlanta, where Charlie Culberson played six positions (plus pitcher) last year, Camargo—who played second and short in 2018 in addition to third—is bound for the outfield at least part time.

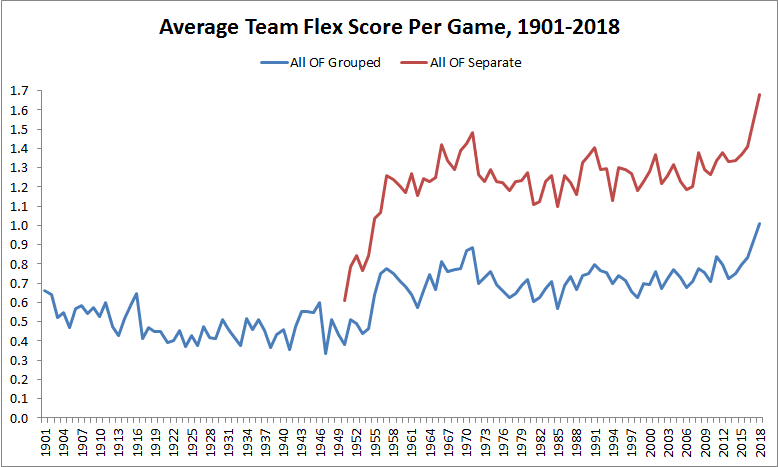

In terms of age, career accomplishments, and even defensive prowess, there’s no clear pattern in the players newly ticketed for utility roles. That list of multiposition converts includes an All-Star player in his prime, multiple mid-30-somethings at the tail end of Hall of Very Good–caliber careers, and young players just embarking on their big league years. As I noted in October in a piece about the positionally fluid Dodgers, the trend toward versatile defenders is easily discernible on a leaguewide level via a metric we’ve dubbed “Flex Score,” which is charted below. The blue line shows the average number of defensive appearances per team game by a player at a position other than his primary one—excluding DH, and lumping all outfield positions together—in every year back to 1901. The red line is similar, but it treats the three outfield positions as discrete spots and covers only seasons since 1950.

Teams have exhibited a preference for more multiposition players over time, but both lines show a sharp uptick in recent years, peaking (so far) in 2018. For more and more fielders, playing “out of position” is the new norm.

This trend isn’t limited to the majors. When the Mariners acquired 23-year-old second baseman Shed Long from the Reds (via the Yankees) on Monday, Mariners GM Jerry Dipoto immediately announced that Long, who hasn’t yet played above Double-A, might be a fit for second, third, left field, and center, even though he hasn’t strayed from second since 2016. “He’s young, athletic, and we think he’ll wind up being multiposition-versatile,” Dipoto said. “Second base will remain his primary position, but he’s too good of an athlete not to try to move him around the field and see what works.”

If Long does branch out in the minors this year, he’ll have plenty of company. According to data provided by Baseball Prospectus, 29 percent of minor leaguers with at least 100 games played in 2018 appeared at more than two positions, and 13 percent spent time at more than three positions. Both of those figures are record highs since at least 1984, when BP’s comprehensive minor league data begins.

Eli White, a 24-year-old 11th-round pick from 2016, was one of Oakland’s top 20 prospects before being dealt to the Texas Rangers in December in the same three-way trade that sent Profar to Oakland. White, a natural shortstop, entered 2018 with prior professional experience in right field and center, and he added second and third to his positional repertoire while jumping from High-A to Double-A. In theory, having to master more positions makes his job more difficult, but perhaps in part because he was introduced to the idea early, he’s taken the challenge in stride. “I enjoy jumping around, and it’s fun coming in and seeing your name in a different spot every day,” White says. “I grew up just playing shortstop my whole life, so that’s kinda like home for me. But it’s been a cool experience getting to play some places in the past couple years that I never have before.”

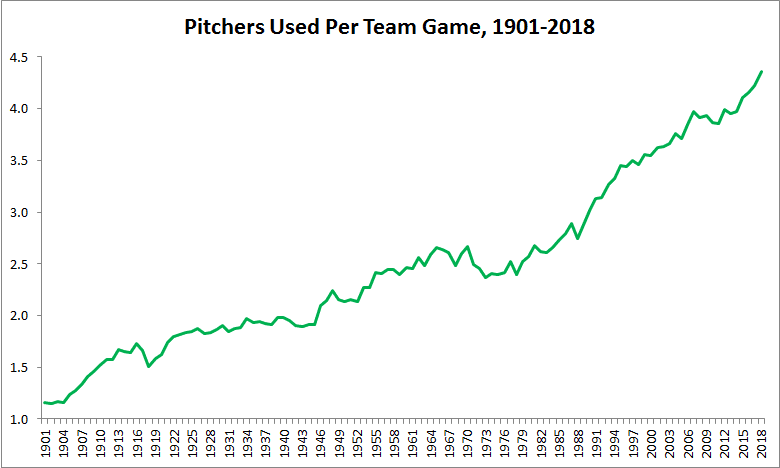

MLB’s multiposition movement is proceeding in parallel with an increase in the average number of pitchers used per team and per game, which swelled to a record 4.4 in 2018.

More pitchers per game mean bigger bullpens; bigger bullpens mean smaller benches; and smaller benches mean more importance placed on being a positional polyglot. The now-standard complement of eight starting position players, eight relievers, and five starting pitchers leaves room for four more nonpitchers. Two of those spots typically go to a backup catcher and a DH or pinch hitter, which reserves one roster spot apiece for a backup infielder and a backup outfielder. The more gloves those players—or players in the starting lineup—can carry and credibly use, the less likely a team is to be caught without a backup, and the better equipped it is to platoon or pinch-hit despite a small selection of position players.

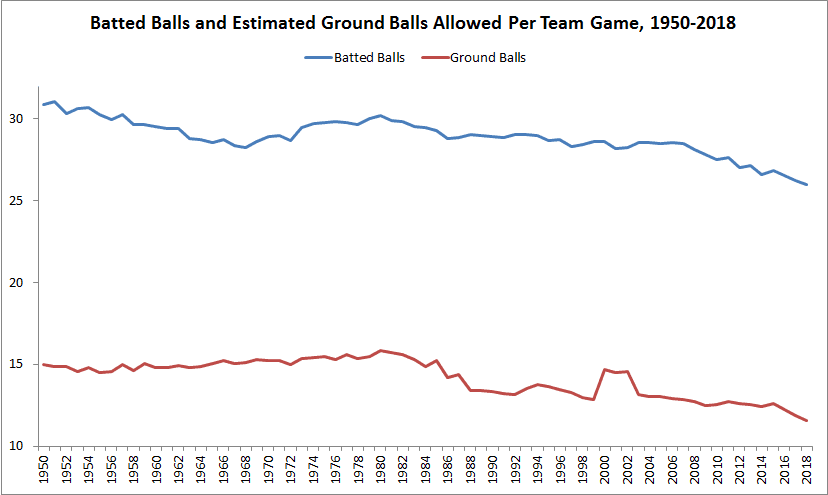

As the influx of pitchers has caused benches to shrink, other developments have made it more feasible for fielders to play additional positions without costing their teams acutely on defense. Last season brought baseball’s highest strikeout rate ever and—thanks to a data-driven embrace of balls in the air, exacerbated both by increased carry on flies and a desire to avoid infield shifts—its lowest ground ball rate on record, according to Baseball Prospectus batted-ball data (from multiple sources) that extends to 1950. Decreasing contact and air-oriented swings have resulted in fewer defensive chances, especially on the ground. In 1951, teams allowed 31.06 batted balls per game; in 2018, they allowed 25.97. In 1980, teams allowed an estimated 15.82 ground balls per game; in 2018, that figure fell to 11.56. Even since 2000, a period during which BP’s batted-ball data comes from a single source (MLB), the average rates of grounders and all batted balls allowed per team game have declined by 3.1 and 2.6, respectively.

With fewer fielding opportunities available, particularly in the infield—and by extension, fewer chances to screw up—it’s easier than ever for players to pass at positions they haven’t practiced extensively. Concurrently, the unprecedented incidence of both standard and extra-adventurous shifts—encouraged by detailed tracking data on pitches, batted balls, and player positioning—has made movement between positions less jarring while also allowing teams to minimize the impact of poor range. When the Brewers traded for third baseman Mike Moustakas last summer, they were comfortable moving incumbent Travis Shaw to the keystone because he’d played on the right side of second during frequent infield shifts. And while optimal positioning doesn’t erase the difference between the best and worst fielders, it may allow players without the archetypal physical profiles for certain positions to achieve some minimum acceptable level of competence. As one assistant GM says, “Positions themselves are more abstract than ever.”

Naturally, not every player can play any position, even in these batted-ball-deprived times, but because the benefits are significant and the penalties aren’t severe, there’s more incentive for teams to develop players in the multiposition mold. Ironically, some free agents with proven utility track records, including Marwin González and Josh Harrison, are still unsigned. Even though the utility role is prized, individual utility players may not be because teams are treating more players as capable of multiposition play.

The rise of Generation Zobrist is part of a larger blurring of the distinctions between baseball’s traditional positions and roles. The line between starting pitchers and relievers is growing fuzzier by the season, as the “opener” spreads and starters are pulled from games earlier to avoid facing the same hitters repeatedly. Shohei Ohtani’s promising experiment in 2018 has opened the door to a larger crop of aspiring two-way players, including Matt Davidson, Michael Lorenzen, Kaleb Cowart, and Brendan McKay. Position-player mop-up pitchers are more inescapable than ever. Part-time catchers like Willians Astudillo and Isiah Kiner-Falefa are making cameos all over the field, furnishing nearly unique combinations of positions.

In an environment where teams are less intent on labeling and limiting their prospects and stars, players with the attitude and athleticism to transcend traditional boundaries are making the unorthodox conventional. And as more players are discovering, being “blocked” at a position is less of a career-killer than an invitation to demonstrate a new skill.

Thanks to Rob McQuown of Baseball Prospectus for research assistance.