On Tuesday night in New York, the Red Sox beat the Yankees for the third time in four games, ending a division series that was pitched primarily by bullpens. For the second straight game, the Yankees’ starting pitcher lasted only three innings, capping a series in which Yankees starters combined for only 13 innings—the second-lowest team total ever in a division series that lasted at least four games, trailing only the 11 ⅓ innings Red Sox starters mustered in their own losing effort last year. Yet the consensus after the ALDS said that Yankees manager Aaron Boone left his starters in too long—and the consensus was correct. That’s the latest indication of how quickly the evolution of pitcher usage is reducing the role of the starter, particularly in the postseason. And while there’s a sound statistical basis for the sport’s ascendant, bullpen-centric style of play, it’s in some ways less satisfying in a narrative, aesthetic sense.

In his 1970 treatise on punishing pitchers, The Science of Hitting, Ted Williams advised aspiring sluggers that their first time at bat in a given game is “a key to effective hitting, a key to the day you are going to have and therefore a key to your baseball life.” For Williams, the primacy of the first plate appearance was simple. “You figure to face a pitcher three or four times in a game,” he wrote. “The more information you log the first time up, the better your chances the next three. The more you make him pitch, the more information you get.”

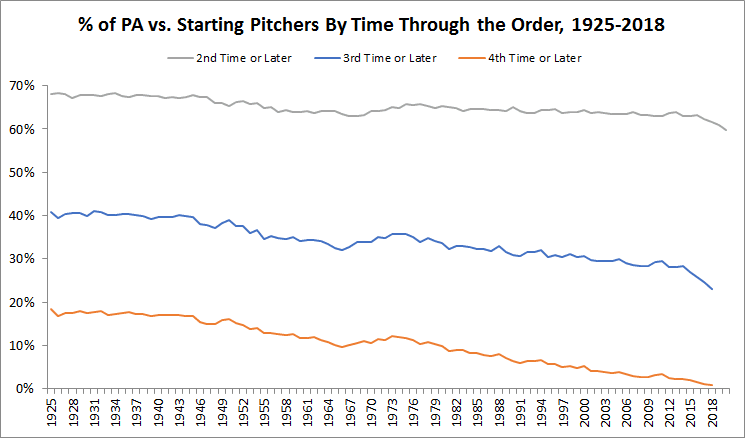

Williams was right. Decades later, sabermetricians quantified what’s come to be called the “times through the order penalty,” a tendency for hitters to perform better each time they face a starting pitcher in the same game. As best we can tell, the phenomenon stems from familiarity, not pitcher fatigue. And as Williams asserted, it’s magnified the longer the look the hitter gets in his first trip to the plate. “The big advantage seems to come from seeing a lot of pitches, especially in the first [plate appearance],” wrote Mitchel Lichtman, who found that hitters who see more than four pitches their first time up gain 2.5 times the advantage in their next PA than hitters who see fewer than three pitches. (Ironically, Williams himself didn’t have a huge times-through-the-order advantage and was no better the third time he faced a starter in a game than he was the first.)

Modern major league teams are well aware of the penalty, and they’ve gone to great lengths to minimize it by preventing pitchers from going to great lengths in games. In 2018, batters’ times-through-the-order advantage was larger than ever, but it also applied less often than in any previous year. During the regular season, an all-time-low 23.0 percent of plate appearances versus starters featured a hitter who was facing the starter for at least the third time in the game.

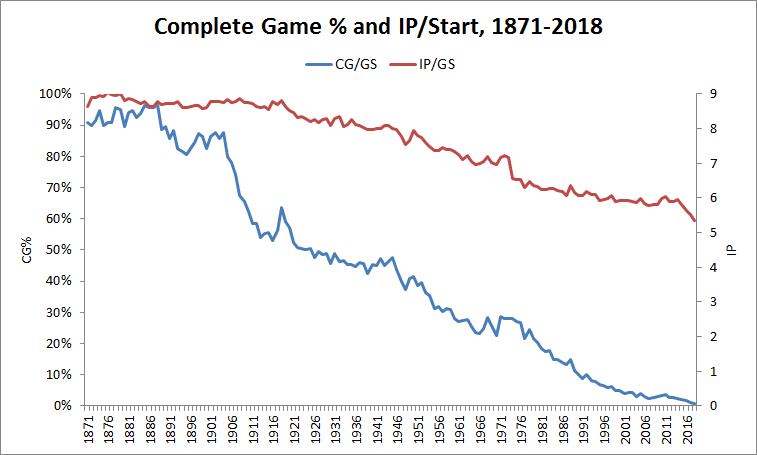

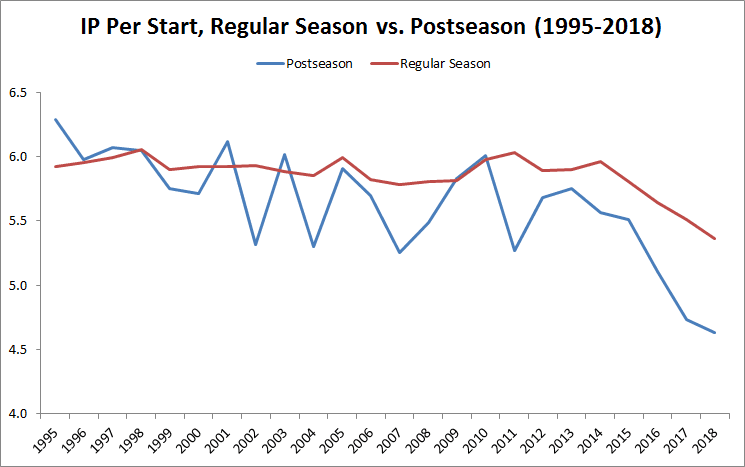

In baseball’s current incarnation, complete games are almost extinct—this year’s league leaders were tied at two—and the average number of innings per start is rapidly falling toward five.

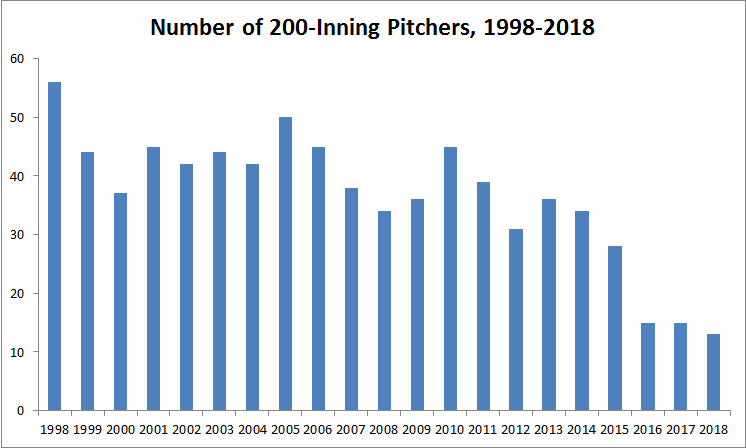

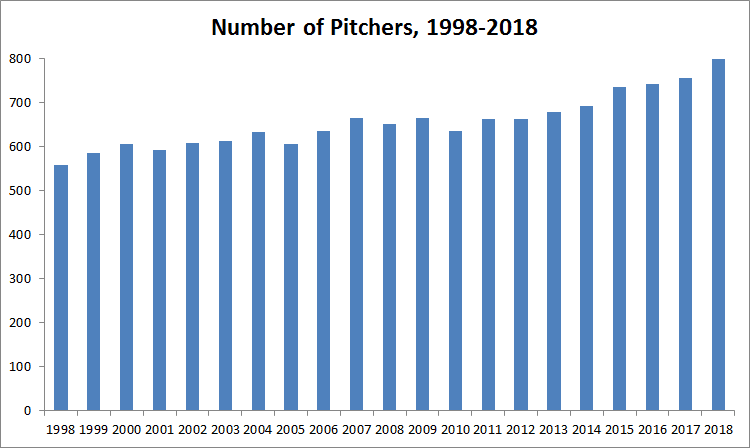

As those long-term trend lines make clear, what we’re seeing today is an extension of a gravitation toward shorter starts that dates back to the 19th century. In that sense, then, we’ve had plenty of time to grow accustomed to the way the game is going. Recently, though, the rate of change has accelerated, to the point that pitcher usage has exhibited something closer to a bright-line break with the past than a gradual difference in degree. The number of 200-inning pitchers per year declined by 50 percent from the last expansion season, 1998, to 2015—a span of 18 seasons. That count has decreased by a further 54 percent in the past three seasons alone.

Between 2014 and 2018, the average length of a start decreased by slightly more than six-tenths of an inning. That’s the biggest decline over any four-year period in the game’s history except for the mid-1970s, when the advent of the DH and a ball change helped inflate offense. The past four years have brought another ball-driven increase in offense, but they’ve also seen the arrival of two tactics that are reducing the average time that starters spend on the mound: the opener, and its more extreme cousin, bullpenning. The opener, which the Rays popularized this season, entails beginning a game with a pitcher who lasts an inning or two tops, followed by a “bulk guy”—for all practical purposes, a starter who pitches second. But bullpenning simply stacks inning-or-two-at-a-time guys for all eight or nine frames, virtually doing away with repeat batter-pitcher plate appearances and, by extension, the times-through-the-order effect.

Teams have dabbled in bullpenning before (or at least entertained the idea), and public analysts have long proposed it as a potent postseason strategy. Even before baseball’s first wild-card contest, nerds who Never Played the Game were calling for some bold team to turn the must-win matchup into a bullpen game. “Skip the starter,” FanGraphs writer Dave Cameron advised in September 2012, arguing that parading relievers one after another from the beginning of the game would maximize the odds of winning a do-or-die showdown. Cameron (who now works in the Padres’ front office) and other FanGraphs writers repeated the plea in subsequent seasons, and many more writers of a sabermetric persuasion took up the cry, but no team took the suggestion until last Wednesday night, when the A’s attempted to bullpen their way past the Yankees. There was no mystery to the team’s motivation: “It’s the numbers,” manager Bob Melvin said, citing a desire to avoid “the third time around.” Oakland didn’t advance, but not clearly because of the bullpen game; the all-bullpen approach offers an incremental probability boost, not a guarantee, and there’s no reason to think that starting, say, Edwin Jackson would have worked any better. The next day, the Brewers provided proof of concept by bullpenning en route to a 3-2 win against the Rockies, whom Milwaukee would sweep despite receiving only 12 2/3 innings from its starting pitchers, a record low for a victorious team in a division series.

As I wrote in 2016, “postseason games are leading indicators, early warning signs that tell us where regular-season baseball might be headed.” Thus far this postseason, relievers have pitched a record 48.8 percent of innings, up from a previous-record 46.5 percent in 2017. That’s excluding the A’s and Brewers’ bullpen-game “starters”; lump Liam Hendriks and Brandon Woodruff in with the relievers, and the bullpen-inning percentage rises to 50.2, with the average length of a start sinking below five innings for the second straight October. The bullpen proportion in the regular season may never climb quite that high—the shortage of off days in the 162-game schedule makes it more difficult to ride relievers as hard—but it did surpass 40 percent for the first time this season, and it probably hasn’t come close to peaking. Strategically speaking, reallocating innings to relievers and, at times, even all-out bullpenning makes sense, for reasons that Williams would have understood. But it doesn’t come without costs from a spectator standpoint.

Putting possible salary ramifications for starters aside and focusing on in-game concerns, one could object to bullpenning on the grounds that it suppresses scoring, raises strikeout rates, increases the frequency of pitching changes (thereby slowing and lengthening games), and restricts the size of benches, limiting tactical flexibility on the offensive side. And while contemporary pitcher usage hasn’t killed comebacks, it has likely made them less common than they would be if shutdown pens had never evolved. Those arguments are out there, and they aren’t wrong. To me, though, they aren’t the tactic’s most insidious downside. Some of those perceived problems could be combated, either wholly or in part, by obvious measures, such as shrinking the strike zone, moving the mound, installing a pitch clock, restricting on-the-mound warmup pitches, or adding a 26th roster spot reserved for non-pitchers. But there’s no easy fix for the fact that the starter’s starring role in the story of most games has dwindled into a supporting part in an ever-expanding ensemble.

Baseball is more rigid than most major sports in how it distributes screen time. In football, basketball, soccer, and hockey, teams can give the ball to their best players in the moments that matter most. But a baseball club can’t call on its best hitter in the most pivotal plate appearance or stick its slickest fielder in the path of the ball; the best it can do is put the hitter in the heart of the order or make the fielder stand somewhere that tends to see a lot of action, increasing the chances that those skills will go to greater use. Often, it doesn’t work out that way: A slugger might never come up with runners on base, and a fielder might go a whole game without recording a putout. From play to play, the principals change: Hitters revolve in and out of the batter’s box, and different fielders get their gloves on the ball (or watch while the batter strikes out).

Historically, the exception has been the starting pitcher. Yes, the catcher is a constant, but he’s squatting and obscured, and so much of what he does is either opaque on purpose (pitch-calling) or so subtle as to go almost unnoticed (framing). As Roger Angell wrote, “Our awareness of the catcher is glancing and distracted.” The starting pitcher, though, has been baseball’s combined quarterback, conductor, and emcee. He’s the player with the plurality (or maybe the majority) of the on-camera close-ups during the time between pitches, and the one who initiates the action. He holds the conch, and the timing of every other player’s pre-pitch routine hinges on his first movement. Each game tells a separate story, but the starting pitcher is always the best bet to be the protagonist.

The starter’s central role ensures that the game’s plot is always progressing and that the suspense slowly builds even in the absence of scoring. The times-through-the-order effect is a threat that requires constant creativity: To fight familiarity, starters hold offerings in reserve early on and mix in more pitches as the game goes on to try to show each hitter something he hasn’t seen. What transpires in one plate appearance helps set up the next. If a hitter looked bad on one pitch, he might get it again; on the other hand, he knows that, and he should be better prepared for his second crack (although the starter knows that too). In a bullpen game, batters and pitchers are usually facing each other for the first time that day. Granted, easily available video and sophisticated scouting reports have made both batters and pitchers better educated about their opponents before every at-bat begins, but that preparation happens off screen, far from fans’ eyes.

A durable starter also supplies the potential for character growth: He might lack feel for a certain pitch and find it as the game goes on or iron out a mechanical quirk and get into a groove. However events unfold, the starter is the throughline, the source of the subplots that give the game greater continuity and nuance. And as his pitch count climbs, so does the anxiety of the spectator who searches his face and his radar readings for signs of fatigue. Speaking of pitch counts: When starters stay in for the long haul, every at-bat has heightened stakes, because an extra pitch fouled off in the first inning could conceivably come back to bite him in the seventh. In a bullpen game, it’s still smart to be selective, but there’s little cumulative benefit to grinding out every at-bat, no extra incentive for a patient lineup to make a pitcher pay later on by turning every out into a pyrrhic plate appearance. A Red Sox fan, Micah Baum, emailed me on Monday to report a recent “subtle change” in how he views his team’s approach to opposing pitchers. “I used to root for long at-bats that would ‘work the count’ and get the starter out of the game earlier,” he wrote, “but against the Yankees I find myself rooting for the Red Sox to somehow score without encouraging Aaron Boone to take out the starter, so that the Sox can avoid the Yankees bullpen for as long as possible.” (Graciously, Boone obliged.) In more and more games, anticipation of the starter tiring has turned to dread of the next nasty arm coming in.

However inefficient the stats said it was, a head-to-head battle between aces who went deep into games was—and occasionally still is—a source of excitement that transcends the competition between teams. It’s the closest baseball comes to a heavyweight title bout. We still get marquee matchups, but they don’t define the game as often; in the playoffs, even a Justin Verlander–Corey Kluber confrontation like last Friday’s is liable to be limited to not much more than 10 innings combined. We’re less likely to see a signature start that lives on as legend, and more likely to see a solid six innings followed by a couple clean outings from generic right-handed relievers who don’t amass enough innings a year to have high profiles and whose names we’ll forget in a few years. Even the spectacle of an ace starter coming out of the bullpen might not seem as special if the lines between roles continue to blur; Chris Sale coming out of the pen in Game 4 was exciting, but four days after he went only 5 ⅓ in Game 1, it didn’t seem superhuman.

Some of the most memorable playoff moments come when a manager is forced to decide whether to stick with his starter in the late innings. If the skipper stays with his horse—Jack Morris, maybe, or John Smoltz or Curt Schilling—and escapes unscathed, the starter is deservedly celebrated; for both men, it’s a moment that can make a career and lead an obituary. But if he trusts him too long or a pitching change backfires, the decision is dissected for decades, forever linking the names with what-ifs: Bucky Harris and Walter Johnson; Grady Little and Pedro Martínez; Matt Williams and Jordan Zimmermann; Terry Collins and Matt Harvey. Managers still have to decide when to go to the pen, but those critical junctures are coming much earlier in the game, when the ramifications aren’t quite as clear; the debate about whether to pull Luis Severino after the third or bring him back for the fourth just doesn’t have the same juice that it would three innings later.

The news about bullpenning isn’t all bad. Some fans and analysts feel a certain satisfaction in knowing that teams are seizing every potential point of win expectancy. And after years of unrequited blogging about bullpenning and openers, the sabermetric community can take pride in the knowledge that teams finally listened or reached the same conclusion. There’s also a novelty to bullpenning that makes the tactic intriguing (although that newness will wear off). Elite starters aren’t extinct, and the best ones still get to go long, at least relative to today’s standards. For now, the would-be starters who get bumped by bullpen games and openers are the ones we’re least excited to see. And there’s something to be said for not needing to save one’s strength for pitching in a pinch; every pitcher can throw his hardest at all times, which is bad news for hitters (and elbows) but good news for fans who want the GIFs to keep coming. So no, the ascendance of bullpenning isn’t another reason to declare that baseball is dying; at most, the creeping demise of the starter could contribute to the difference between baseball being good and baseball being even better.

But baseball is, for most spectators, a TV show. And although it’s not scripted, it does depend on a cast of compelling, recurring characters with whom we have histories. “Something we learned from Wings, that we employed when we were creating Frasier, is keep your cast small,” Cheers writer and Wings and Frasier cocreator Peter Casey once told me. “Don’t have a big cast, because in real life, they’re all actors, they all want their lines. And if you have 11 characters in a show that’s only 22 minutes long, everybody’s gotta get fed.” A big cast, Casey said, can become unwieldy. One might say the same about a big bullpen.

Over the past two decades, the number of pitchers used per season has risen more than 43 percent, without any corresponding increase in the count of teams or games. On the plus side, we get greater variety: Bullpens are big enough for beings as distinct as Kazuhisa Makita and Pat Venditte and Jordan Hicks. But because of baseball’s bullpen expansion, fresh faces and arms are constantly cycling on and off of rosters, flitting between Triple-A and MLB so fast that following a staff starts to seem like speed dating. After years of lamenting the third time through the order, we’re getting the quick hooks we wished for. But either way, a penalty has to be paid.

Thanks to Dan Hirsch of Baseball Reference for research assistance.