There are universal reasons to revere Tom Petty, and there are deeply personal reasons to revere Tom Petty. Forgive me, in the wake of news of Petty’s death, at 66, if I start off with a personal one.

I sang a Tom Petty song to my newborn son, my first, the very first time I held him, right there in the hospital, in our first two minutes together. I didn’t plan this. Singing something gentle and soothing just felt like the right thing—the fatherly thing—to do. It could’ve been any vaguely lullaby-ish song by anyone. But in that moment, frantically casting about for something up to the humbleness of the task and the momentousness of the moment, I settled at random on “Alright for Now,” a B-side from Petty’s 1989 god-level album, Full Moon Fever. Just a few acoustic guitars, a few light vocal harmonies, and that voice, weathered and honeyed, dipping sweet and low on the word you:

Goodnight baby

Sleep tight my love

May god watch over

You from above

Judging from this fan-made video of the song filled with sleeping babies and toddlers, plenty of other frazzled and lovestruck new parents had the same idea. It was a seemingly personal gesture that turned out to be universal. Welcome to earth, little buddy. Here’s a voice you oughta get to know.

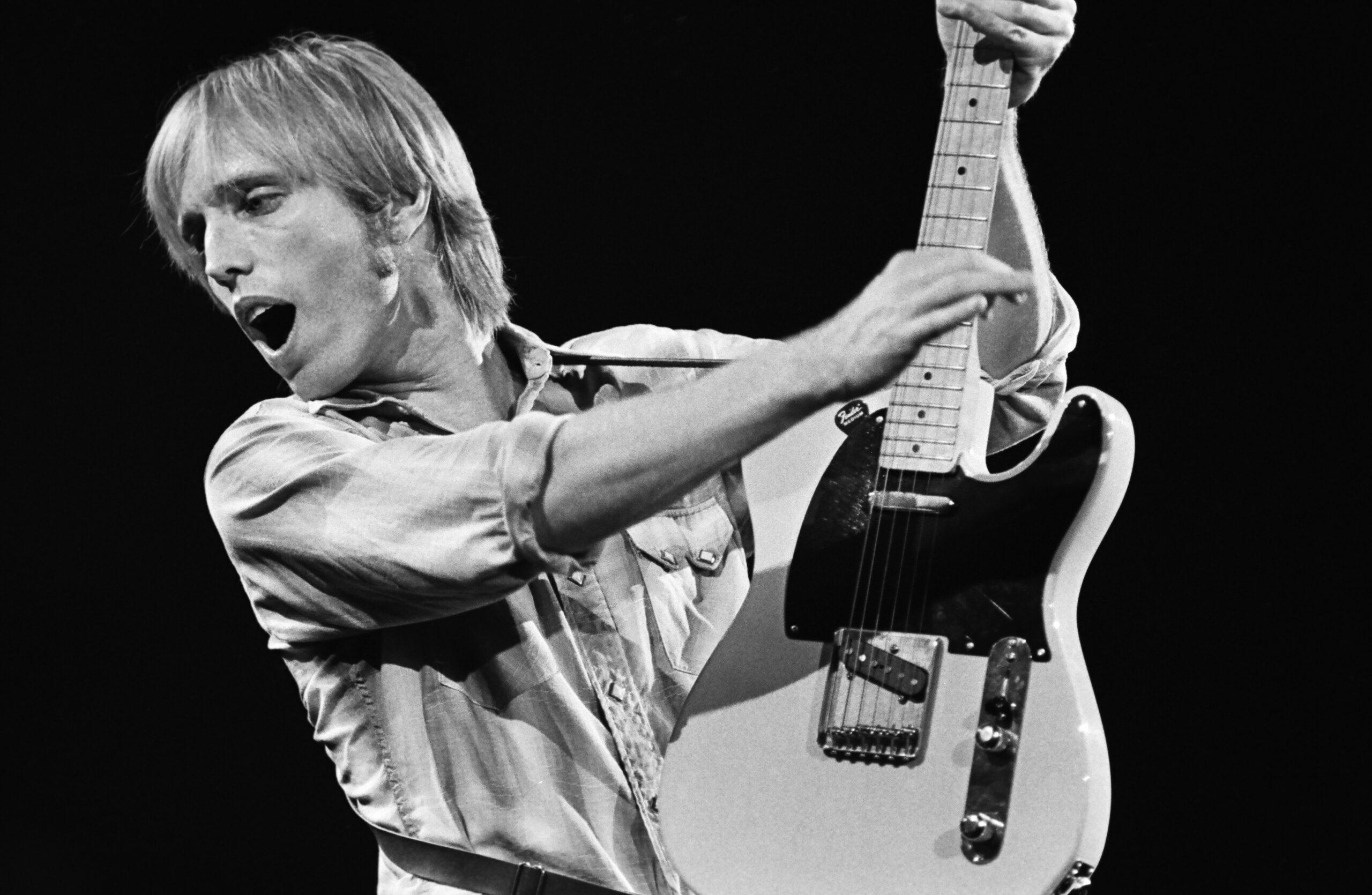

Petty died Monday after suffering cardiac arrest in the early morning; his family confirmed his passing in a statement. Even as a very casual fan, or a total agnostic—as an American, or as any human anywhere with the slightest interest in the theoretical greatness of America—you likely know roughly 25 Tom Petty songs more or less by heart. Know by heart is a very different notion from have them memorized. Petty was born in 1950 in Gainesville, Florida; his first album, Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers, came out in 1976, his scraggly backing band already a central part of the deal, his leadership a relatively modest and muted affair. (Talking to Rolling Stone earlier this year during the band’s 40th-anniversary tour, he described his role as “the older brother they sometimes have to listen to.”) Petty does get that debut record’s cover photo to himself, looking simultaneously like a 20-something and a 50-something—already wizened, already timeless. It’s a spare, raucous, splendid little rock ’n’ roll album that saves “American Girl” for the very end, a sneak attack, a jangling and roaring highway supernova.

That’s how Petty’s career started. In their first 11 years, the band made seven albums, each firing off an all-timer or three, high-school-yearbook quotes and tombstone epitaphs at the ready, from 1979’s Damn the Torpedoes (“Even the losers get lucky sometimes”) to 1981’s Hard Promises (“The waiting is the hardest part”) to 1982’s Long After Dark (“You got lucky, babe, when I found you”). On 1985’s Southern Accents, Petty slowed down and got both a little strident and a little homesick: “I got my own way of talkin’ / But everything is done / With a Southern accent / Where I come from.”

But by then he already belonged to everybody everywhere, defining and uniting America as well as anybody, and more casually than anybody. He was classic rock in real time, the songs monuments to themselves at first contact. I will ride for the whole of 1989’s Full Moon Fever, one of his few solo albums, until I die. It is rugged and pristine, a greatest-hits collection all its own, from the karaoke joy bomb “Free Fallin’” to the bracing secret-agent snarl of “Runnin’ Down a Dream” to his gorgeous cover of the Byrds’ “Feel a Whole Lot Better,” a thrilling mixture of vivid color and reverent black and white. Petty described the whole package to Rolling Stone as a “nearly” perfect album, save a goofy throwaway called “Zombie Zoo” that he came to loathe, but he’s wrong. That song’s somehow perfect, too.

Petty did awfully well for himself amid the early-’90s alt-rock-radio squall, an elder statesman with the songcraft of a Hall of Famer but the spry energy of a lanky and disaffected teenager. My single favorite moment of any song he ever did was the long, swooning coda to “It’s Good to be King,” off 1994’s Wildflowers, the gentle and bone-simple piano riff suddenly blossoming into a gorgeous and profoundly emo arpeggio, an understated string section pushing it heavenward. Even as a teenager in thrall to all manner of far more blaring and visceral angst, nothing ever hit me quite as hard as that song’s final minute, a hint of the exquisite joys and pains of adulthood to come.

Get a load of the set list from his last show, last week at L.A.’s Hollywood Bowl.

One of the only new songs on there is “I Should Have Known It,” from 2010’s Mojo, a jovially surly and bluesy deal suggesting a guy with enough ease to deliver all the hits but with enough leftover unease to keep trying to write new ones. In his later years, Petty toured arenas but also reached even further back into the past, reconvening his pre-fame ’70s Southern rock band Mudcrutch for a new album and a big tour. He and the Heartbreakers also did relatively intimate theater gigs with a deeper set list that allowed the boys to temporarily escape the tyranny of playing “Free Fallin’” every night. He could play 25 straight songs you knew by heart; he could play 25 songs a casual fan might not know at all but would be tempted to commit to heart immediately.

One of Petty’s finest 21st-century moments was in a decidedly supporting role. The 2004 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony is famous for its all-star jam on the Beatles’ “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” with Petty on lead vocals, paying tribute to George Harrison as well as anyone alive could. But Prince, of course, leaps onstage halfway through and fires off what might well be the single best guitar solo of the past 20 years, a volcanically uncouth tirade that blows away everyone onstage by design.

For some reason—and I’m sorry about it now—I always thought Petty was secretly fuming as Prince went on and on and on. A consequence of Petty’s “20-something going on 50-something” look is that his songs would radiate a youthful all-American joy that didn’t necessarily always resonate in his, you know, face. He took his fun very seriously. But I watch this video now and I see Petty providing expert support, making himself invisible but indispensable, shrewdly letting greatness happen without making a big fuss about it. He’s loving it. He’s content just to be part of it. He was the straight man America needed right then, and always needed, and will always unabashedly love.