“What amateur or professional has not racked his brain as he stood at the bat to discover what the pitcher was doing and going to do with the ball twisted up in his hands behind his back?” —The Chicago Tribune, 1887

“A pitcher who allows the batsman to see the ball all the time is at a disadvantage.” —New York Giants pitcher Les German, 1894

The 509th appearance of Yusmeiro Petit’s major league career played out like a lot of the preceding 508. On September 18 in Anaheim, the right-handed reliever was summoned to protect a 3-1 Oakland lead and help seal a win that would keep the A’s in the American League wild-card race. The appearance was Petit’s 72nd of the season, which tied him for the American League lead, but the 36-year-old with the graying goatee wasn’t too fatigued to do his job.

Petit threw an 89.1 mph fastball that got Angels infielder Jack Mayfield to tap a 73.2 mph groundout to third. He struck out Brandon Marsh swinging on an 82.7 mph changeup. Then he tossed a 77.6 mph curveball that induced David Fletcher to send a 49.7 mph popup into the catcher’s glove. Petit had held the lead in an eventual A’s victory, and he’d done it without ever quite touching 90 miles per hour. In the process, he’d demonstrated an understated and underrated skill that may soon be baseball’s next coveted commodity.

As Petit completed the competent, easy-to-overlook inning, Angels TV analyst Mark Gubicza—who pitched for 14 seasons in the majors, as has Petit—became the latest in a line of flabbergasted baseball people to marvel at the righty’s trademark trick, which has helped him thrive in the big leagues for far longer than expected for someone who throws as softly as he does.

“He hides the baseball so well,” Gubicza said. “You’re at the plate and you see a pitcher hide the baseball, keeping that front shoulder in, and you see the baseball out of the hand and you’re thinking, ‘OK, it looks just like a fastball.’ Changeup! … If you have the baseball out in your hand, if you’re not as deceptive as Petit is, you can at least see the grip. … But when you’re hiding the baseball and all of a sudden as a hitter you’re reacting to seeing the ball, it’s already out of the hand by the time you get a chance to recognize between a changeup and fastball.”

Petit’s four-seam “fastballs” this season have averaged 87.6 mph. The average right-handed reliever’s four-seamer has sat at 94.4, almost 7 mph faster than that (and a tick and a half harder than the fastest tracked pitch Petit has ever thrown). The only righty reliever who’s thrown 1,000 pitches this season with a slower standard four-seamer than Petit’s is a submariner, the Giants’ Tyler Rogers. Yet Petit has been both durable and above average, as he is every year.

In 76 appearances, one short of the MLB lead, Petit has posted a solid 3.54 ERA—his highest mark since 2016. Over the past five seasons, only three pitchers who’ve made one start or less—hard-throwing closers Josh Hader, Raisel Iglesias, and Craig Kimbrel—have amassed more Baseball-Reference WAR, and Hader is the lone reliever who leads Petit in context-neutral wins (WPA/LI). Among pitchers with at least 300 innings pitched from 2017 to 2021, only four aces and two closers—Jacob deGrom, Max Scherzer, Clayton Kershaw, Justin Verlander, Blake Treinen, and Iglesias—have lower ERAs. No regular reliever in that same span has appeared in as many games or pitched as many innings. Petit has been, by most measures, one of baseball’s best bullpen arms.

Petit may be best known for being one of only two players (along with two-time teammate Guillermo Quiroz) to play for a team that won a Little League World Series and an MLB World Series, or for setting a still-standing MLB record for retiring 46 consecutive batters in 2014. Despite his consistently strong stats, he has never been an All-Star. He’s never recorded more than four saves or earned more than $5.5 million in a single season. He’s never gotten GIFed by the Pitching Ninja. (The only tweet about Petit from Rob Friedman’s @PitchingNinja account references a video of flamethrowing former teammate Jesús Luzardo testifying to Petit’s “pitchability,” a compliment typically paid to pitchers who aren’t known for nasty stuff.) Yet Petit is the epitome of a pitching ninja—a skilled practitioner who performs his task so stealthily that he tends to go unnoticed, except by the foes he defeats. He beats batters with one hand behind his back—and, perhaps, behind his head and his elbow. “My hand starts in the back, and I get it up behind my head,” Petit says.

“It was always good to compete against him, but not really, because he always ends up getting you out,” says Elvis Andrus, who played with Petit in Venezuela in 2012–13 and became his teammate again this season. In between, he faced him 18 times, with only two singles and a double to show for it. “You don’t see the ball until it’s already in the catcher’s mitt,” Andrus says. “That deception helps him so much.”

The qualities that create Petit’s “invisiball” may not stay so low profile for long. Deception could be the next catcher framing or spin rate, two other unobtrusive aspects of performance that are now targeted and taught with greater urgency because technological breakthroughs made them easier to isolate and value. If so, then Petit is poised to be the poster boy for the power of deception, just as José Molina and Jonathan Lucroy were for framing or Rich Hill and Collin McHugh were for spin. As a low-velocity, low-spin pitcher who doesn’t miss many bats, Petit appears to be miscast as a late-inning option in the era of blistering fastballs and skyrocketing strikeout rates. But advances in baseball biomechanics and body tracking are finally giving evaluators objective means of measuring Petit’s sleight of hand—and, perhaps, of discovering and developing other arms like his.

In the wake of baseball’s foreign-substance crackdown and subsequent downturns in spin and movement, the legal deception conferred by a ball-hiding delivery holds even greater appeal. And because ball hiding historically hasn’t been factored into metrics that appraise pitchers based on pitch characteristics alone, pitchers whose deception makes their middling movement, speed, and spin play up exhibit all the ingredients of a good old-fashioned market inefficiency. “Since most teams are becoming more reliant on their [stuff-based] models, stuff is likely getting more expensive/coveted,” says one pitching analyst who has worked and consulted for clubs. “I’d imagine that this makes any quantification of deception that much more valuable.”

Four-time All-Star Hunter Pence has witnessed Petit’s prowess at playing peekaboo with batters from multiple vantage points: as a teammate of Petit’s on the 2012–15 Giants (who was inches away from helping Petit preserve a perfect game) and as an opposing hitter who struggled against him at the plate, going 1-for-10 with a single in 12 career plate appearances. “The fact that Petit’s done it without the power tells me that there’s something in his mechanics that needs to be studied and more people need to be emulating,” Pence says. “Because he’s not the huge velocity [guy], not everyone’s really studying what he’s doing, but he’s been [producing] elite numbers for such a long time. It makes you wonder, if you get someone like a young player with a lot of speed and power, [whether] they could gain a lot from trying to emulate what he’s doing.”

Pence isn’t the only one wondering.

To plumb the depths of deception, one has to understand why it’s helpful for hitters to take a gander at the ball before its flight begins.

“Sometimes you’ll have pitchers that throw really hard, but they show you the ball the whole time they’re throwing so you can kind of follow it,” Pence says. “Petit has it behind his body and his head.” Obscuring the ball prevents Petit’s opponents from getting a glimpse of the grip or absorbing the myriad subconscious cues that help hitters perform the feat often labeled the toughest task in sports. “The longer you see it, the easier it is to decide, to recognize, to figure out what’s happening,” Pence continues. Thus, as a hitter, “you want to create time. He’s shortened that amount of time. … You can’t really pick up anything from someone like Petit.”

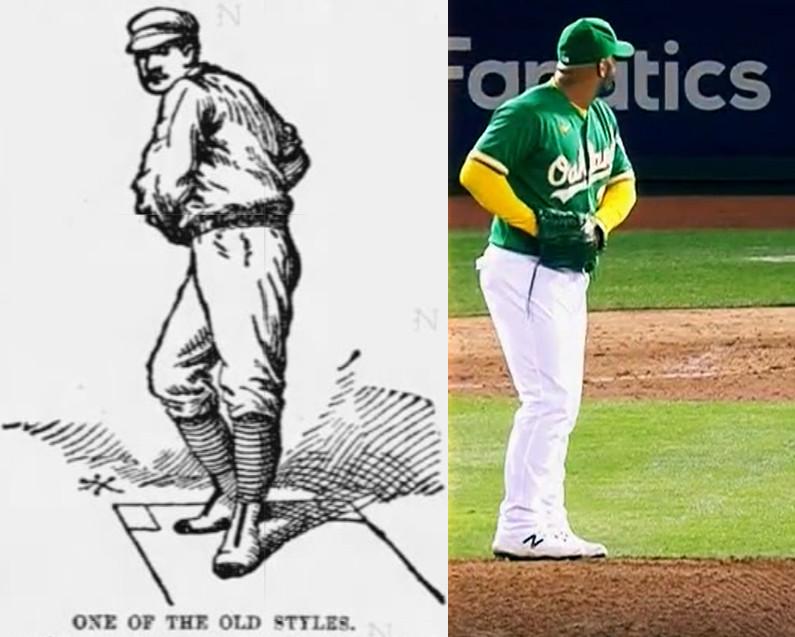

Pitchers pioneered deceptive subterfuge ages before Petit fooled his first hitter. Until the 1890s, few pitchers wore gloves, which made it hard to hide the ball. Some pitchers tackled that problem by adopting deceptive deliveries, in which they would turn their backs to the batter. (Following Luis Tiant’s mid-career reinvention almost a century later, he would do the same—and thereafter, he did better from the windup than from the stretch.) The deceptive trailblazers’ contortions sparked a series of rules changes that required pitchers to face forward and plainly present the ball. Of course, pitchers did what they could to skirt that requirement.

“While every pitcher obeys the rule by holding the ball in front while getting ready, he invariably temporarily puts it out of sight behind him just before his arm swings forward, thus succeeding after all in getting it momentarily beyond the line of vision of the batsman,” an 1895 newspaper report said, explaining that the more deceptive the delivery, “the more difficult it is for the batsman to measure the angle of the approaching sphere.” In 1910, Johnny Evers and Hugh Fullerton expounded on the practice of “shadowing,” which they said consisted of “the pitcher sidestepping and placing his body on the line of the batter’s vision, so that the ball has no background except the pitcher’s body and the batter cannot see it plainly until the ball almost is upon him.”

The principles of deception are similar today, but now we have tools of detection to go with the gloves. More than 13 years into MLB’s pitch-tracking era, nearly as long into its batted-ball-tracking era, and six years into its player-movement-tracking era, baseball analysts have whittled away at their lists of major known unknowns. The sport isn’t close to a settled science, and every advance generates new questions that previous generations never thought to ask or considered answerable. But fewer and fewer events that occur on the field can’t be recorded or can’t be looked up on a leaderboard. Until recently, deception was one of the stubborn exceptions, placing it in analytical limbo along with such ciphers as pitch sequencing and injury prevention.

In January, the Giants signed southpaw Alex Wood to a one-year, $3 million deal, for which he has richly rewarded them. Giants president of baseball operations Farhan Zaidi told The Athletic’s Andrew Baggarly that Wood, who had pitched for the Dodgers during Zaidi’s days in L.A., was an example of a type of pitcher who had always intrigued him: the deceptive, funky hurler whose pitches are tough to pick up. “Nowadays so many relievers are throwing 96-97, you don’t really hear hitters complain, ‘Man, I just can’t hit that good velocity,’” Zaidi said. “Because they see it so often. But a lot of times I’m talking to a position player about pitchers, or someone brings up a pitcher in an unsolicited way, it’s ‘I can’t see the ball out of that guy’s hand at all.’”

Zaidi described deception as a “counteracting factor” to the industry’s obsession with stuff, which has spurred pitch speeds ever higher, contributed to the escalation of sticky-stuff usage, and prompted players and teams to invest in tech-enhanced approaches to pitch design. “We’ve gotten so much better at evaluating pure pitch quality,” Zaidi continued. “But evaluating deception or uniqueness is a lot more subjective, and that’s where a lot of pitchers can get their effectiveness from.”

Most modern-day pitching analysis concerns concepts that pertain to pitch physics and flight. Seam-shifted wake. Spin mirroring. Vertical approach angle. But deception starts well before the ball leaves the hand and pitch-tracking tech takes over. To paraphrase Joe MacMillan’s quote about computers on Halt and Catch Fire: Deceptive deliveries aren’t the thing; they are the thing that gets you to the thing. And that makes them pretty important.

Zaidi, who’s as numerate as any high-ranking sports executive, cast doubt—publicly, at least—on the potential to reduce deception to a stat, saying, “I don’t know how well you can quantify it.” Oakland pitching coach Scott Emerson says the same about Petit: “He stays on-line, he gets his ball out in front, but he’s also closed going down that mound. He’s hiding the ball as long as possible, and all of a sudden he’s down in the bottom of the mound and he’s coming right at you, and that’s the deception part that most people really can’t quantify.” On a recent podcast, the Pitching Ninja himself echoed a similar sentiment, saying, “The one thing that we really have a hard time doing today is measuring deception.”

Yet some teams and instructors are trying, bolstered by increasingly perceptive cameras and computers. Modeling deception is a necessary step in developing a Grand Unified Theory of pitching. And it may not be long until deception becomes the latest supposedly unmeasurable quality to yield its secrets to the sport’s inexorable drive toward data. “There’s no question that modern technologies have improved the industry’s ability to identify when deception is happening and better assess how it’s happening,” says Mariners president of baseball operations Jerry Dipoto, a longtime extoller of the virtues of deception. “There’s also no doubt that modern coaching trends have enhanced our industry’s ability to teach it, based on a pitcher’s body movement profile.”

What does Dipoto—or, for that matter, anyone else—mean by “deception”? It depends on the person and the pitcher. Detecting deception is difficult by design, but defining deception isn’t much easier.

On a fundamental level, every aspect of pitching is intended to deceive. As pitcher and author Jim Brosnan wrote in The Long Season, in response to the balk rule’s “deceiving” the runner, “What in hell do they think a pitcher is doing when he throws a curve ball? If deceit is, in truth, a flagrant violation of baseball morality, then the next logical step is to ban breaking balls, and let the hitter call his pitch.” Pitchers try to camouflage which pitches they’re throwing and where those offerings are going to go, while hitters try to penetrate the ruse. But the word “deception” is generally reserved for any tactic or trait that makes a pitch harder to hit than its flight through the air would indicate.

Some forms of deception have more to do with rarity than inherent hard-to-hit-ness. An outlier like Rogers, for instance, is tough to square up partly because hitters tend not to practice against pitchers who release the ball from ankle height. Simple scarcity helps explain why left-handed pitchers, as a group, get away with less velocity than righties: Hitters don’t face them as often, especially before they make the majors. “Hitters basically develop decision models for when and where to swing based on an unknown number of primary sources, and these models surely take hundreds/thousands of pitches to refine,” says Kyle Lindley, a sports scientist at Driveline Baseball. “If you can achieve nasty stuff in a way that is different from the pitchers whose mechanics and pitch flight are being used by hitters to learn how to make swing decisions, that sounds like the winning recipe.”

Unless you’re switch pitcher Pat Venditte—or, judging by Venditte’s stats, even if you are—you can’t effectively fake crafty lefty-ness if you’re a natural right-hander. Nor is it easy to drop down like Rogers (or even deceptive Twins rookie Joe Ryan). But dramatic reinventions aren’t the only recourse in the pursuit of deception. There’s tunneling, the technique of aligning pitch trajectories such that one pitch type looks like another until it’s too late for hitters to react. There’s slot changing, or variation in arm angles from pitch to pitch, which prevents hitters from expecting the ball to come out of a certain slot. There’s also, confusingly, consistency in arm angles (and arm speeds) across different pitch types, which prevents hitters from telling the types apart. There’s expanding or abridging the time between deliveries, or altering the delivery itself, the calling card of the Giants’ Johnny Cueto and the Yankees’ Néstor Cortes Jr.

Then there’s the art of staging a diversion mid-delivery. Some scouts draw a distinction between deception and distraction—the latter of which could come from a violent, herky-jerky motion that looks like a blur of arms and legs—but whichever term one chooses to use, the effect is to draw hitters’ attention away from where they want it to be. Hall of Famer Warren Spahn, who’s credited with the maxim “Hitting is timing; pitching is upsetting timing,” was one of the best distractors of his day, thanks in part to an exaggerated leg kick. “The high leg kick was a part of the deception to the hitter,” Spahn said. “Hitters said the ball seemed to come out of my uniform.’’

But ball hiding is separate from most of those traits. Deceptiveness contains multitudes, making a complete taxonomy of deception elusive. One high-ranking executive offers six sub-categories of ball hiders (slot changers included), some of which may overlap. Body shielders, who hide the arm and sometimes throw across the body in a “crossfire” style whose origins can be traced to the 19th century. Short armers, who keep the ball close to the trunk and head. In-liners or late armers, who extend their throwing arm behind them and delay the arm’s entry into the throwing zone. Long striders, who release the ball uncommonly close to home plate. High front siders, who lead with their glove arm at head height or higher and bring the throwing arm down through the same slot.

Traditionally, deception has been kind of a catchall term that doesn’t do a good job of distinguishing between types of deception. “Scouts/baseball people have a hard time differentiating between different kinds of deception, and lots of guys end up getting thrown into the ‘hides the ball’ bucket when in reality, they just have funky deliveries that throw off a hitter’s visual timing,” says one front-office analyst. But another team analyst believes that baseball’s vocabulary is catching up with gains in knowledge. “The meaning of deception has probably changed a bit over time,” he says. “It seems to often describe the effectiveness of a pitcher beyond what we’re able to directly observe or quantify. A pitcher’s ability to create extension, backspin, riding life, approach angle, are all things that 10 years ago might have been called deceptive, but now we might use those more precise descriptions.”

Petit’s delivery leverages at least two types of deception: He’s a hider and a strider. “Between hiding the ball visually and just his natural extension and ability to stride out that far, he has two outlier qualities that I think have formed a really nice synergy,” says former big leaguer Brian Bannister, the Giants’ director of pitching. Bannister would know: He was Petit’s teammate and occasional throwing partner throughout the Mets’ minor league system, dating back to Low-A in 2003. Thanks to Petit’s gift for deception and his precocious commitment to perfecting his craft, even playing catch could be a challenge.

“No coach was advocating for it, but he consciously tried to hide the ball behind his torso with his arm action on every throw he made, even in catch play,” Bannister recounts. “He’d turn his torso back toward second base and then have a shorter arm action and really just try to keep the ball visually directly behind the torso so that the hitter couldn’t see it. And then, as the catch partner, it always felt like it popped out of the back of his head, because you just could never see the ball.”

That was only one of the ways in which watching Petit was humbling for Bannister, who didn’t throw hard either but wasn’t as skilled at deception. “I go to throw my bullpen right after him, and I looked down at where my foot is hitting, and his footprint was a full foot past my foot,” Bannister says. “And I was just blown away. I remember almost trying to jump off the rubber to even get my foot that far, and I could barely do it. And I definitely couldn’t maintain my balance. … He just has this incredibly smooth, deceptive way about getting much closer to home plate than the average guy. I felt I was going to blow up my groin trying to even get my foot that far, and that’s just what he does on an average throw.”

MLB’s Statcast system started tracking extension in 2015. Petit’s 7-foot-1 extension—the average distance in front of the rubber at which he releases the ball—puts him in the 96th percentile among pitchers who’ve thrown at least 100 pitches this season. Although extension is strongly correlated with height and wingspan, it isn’t purely a product of size: Bannister is 6-foot-2, an inch taller than Petit’s listed height. Petit simply strides farther forward than one would expect.

On March 2, 2005, a 20-year-old Petit traveled to the American Sports Medicine Institute in Birmingham for a biomechanical breakdown commissioned by the Mets. Petit wore reflective markers on his body as he threw in front of motion-capture cameras. The 13-page report produced after his session, which was shared with The Ringer, noted that Petit’s elbow stopped 40 degrees of full extension at release, which made it “much more bent than other elite pitchers.” It also cited his “impressive ability to get far out towards home plate.” Petit’s stride length on fastballs was 88 percent of his height, which fell outside the “normative range.”

Every pitcher’s motion blends linear progression toward the plate with side-to-side rotation. “Compared to other pitchers, [Petit] has more of the linear stuff and less of the rotational stuff,” says Dr. Glenn Fleisig, ASMI’s biomechanics research director. “He had a long stride, which gets him closer to home plate. But the trade-off was he had less rotational velocity of spinning his hips and his trunk. … That’s why he might be not a high-velocity thrower, because he has a limited amount of the rotational stuff due to his long stride.” As Petit puts it, “I turn only a little bit.”

According to some sources and studies, extension’s performance-enhancing effects (phrasing) may be modest at best. According to Statcast, Petit’s extension earns him only one more mile per hour of perceived fastball velocity, which if accurate would not be nearly enough to explain his success. However, one leader of a baseball ops department confides that “Hiding the ball in back is potentially as impactful in certain cases as extension out front.” Petit is probably one of those cases.

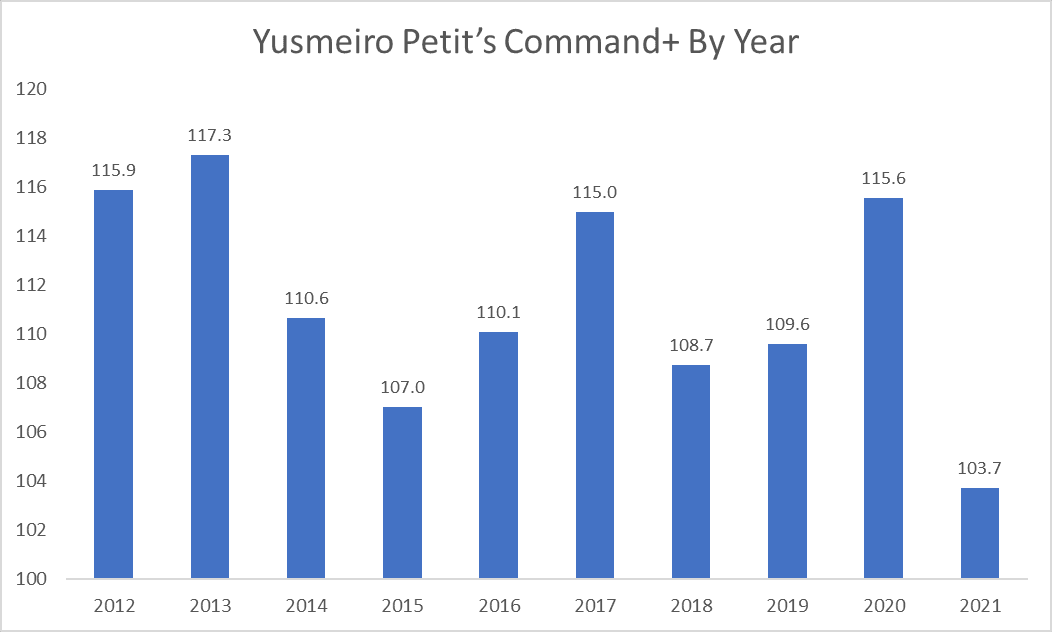

Admittedly, deception isn’t Petit’s only strong suit. He’s also allergic to walks and possesses superb command, as measured by Stats Perform’s metric Command+ (an index stat where 100 is average). On the career Command+ leaderboard, which encompasses seasons from 2011 to present, Petit’s score of 110.2 ranks 53rd out of 1,226 pitchers with at least 1,000 pitches thrown, which puts him in the 96th percentile. (Mariano Rivera leads the list at 120.6.) By his standards, Petit’s command has been a bit off this season, but it still grades out above average.

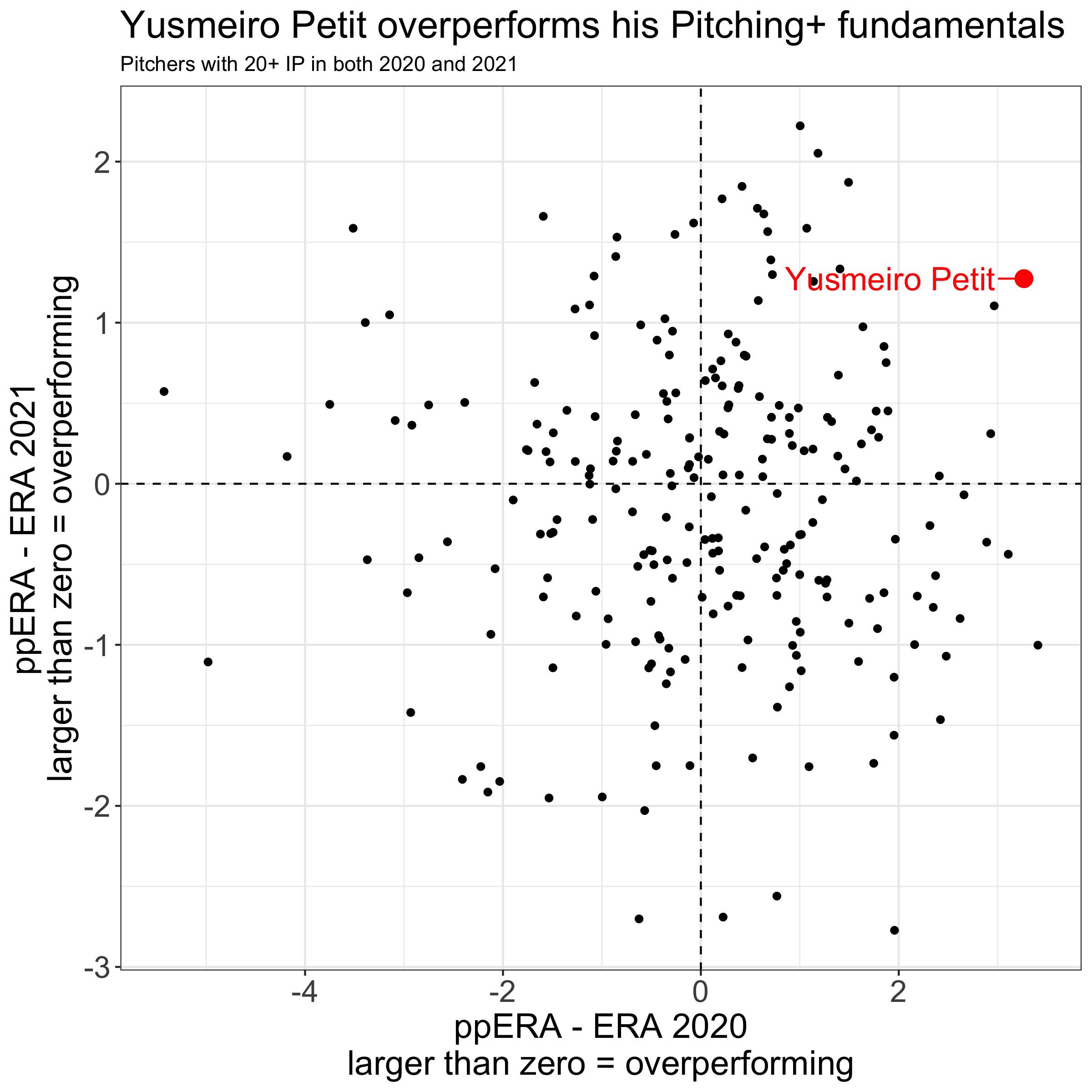

Even so, some portion of Petit’s secret sauce is still missing. Pitching+, a metric developed by Max Bay, combines pitch-quality stat Stuff+ (which factors in extension, among many other inputs) and Location+, a proxy for command. In theory, Pitching+ should account for where Petit puts his pitches, how his pitches behave, and where he releases them. Yet according to calculations by Bay, the pitcher who’s most overperformed Pitching+’s ERA estimates from 2020–21 is … yes, Yusmeiro Petit.

Clearly, what happens before the ball is released must matter. And that’s where markerless motion capture comes in.

One leader of a baseball ops department says that some clubs have probably backed into a deception grade based on performance relative to stuff, but that he hasn’t heard of any front offices using measured delivery elements to put a number on ball hiding. “If there is a club out there that can measure this better than others, I’d imagine they could glean a pretty significant advantage,” the executive says. No team sources I spoke to would divulge that their clubs had developed a deception metric, though another baseball ops decision-maker said that teams that claim to be in the dark about deception are “probably sandbagging to some degree,” even if they haven’t cracked the code as completely as they have when it comes to other aspects of pitching.

Some teams have made rudimentary efforts to suss out deception using video shot from behind home plate, but any sweeping epiphanies derived from tracking data on deliveries would have to have happened recently. Most laboratory-based biomechanical analyses, including ASMI’s, make no attempt to measure deception, opting instead to study how to attain, as Fleisig says, the “best ball performance for the least force on your elbow and shoulder.” Even if those workups could be used to study deception, they aren’t easily scalable and can’t track pitchers in game settings, when they’re amped up and unencumbered by gizmos.

Enter markerless motion-capture systems, the latest breakthrough in baseball’s biomechanics revolution. These systems use sophisticated, computer-powered Human Pose Estimation (HPE) techniques to capture player movements from afar, with no need for wearables. Because they can be installed in a ballpark, they can be used to study pitchers in their natural habitats, coupled with corresponding data about the batter and the ball. Markerless motion capture systems used by MLB teams include KinaTrax, Simi, and, as of last season, Statcast itself, which was upgraded to incorporate Hawk-Eye cameras capable of tracking players’ poses and not just their centers of mass.

“With modern stadium motion-capture systems, we have all the information we need to quantify the position of the ball relative to the batter’s eyes and the pitcher’s body,” says Dr. Jimmy Buffi, the CEO of sports science company Reboot Motion and a former senior analyst for the Dodgers. “Each one of these systems gives us the 3D locations in space of every one of a pitcher’s body parts, so if we also have the location of the ball, the plate, and the batter in 3D (which many of these systems also give us), we can calculate many different things about what the batter is perceiving as the pitcher is delivering the ball to home plate.” One front-office official confirms, “We can measure certain definitions of hiding the ball through markerless motion-tracking technologies, and naturally because of that it is something we would make more of an effort to understand.”

KinaTrax, which debuted in the big leagues in 2015, is currently used by 10 teams. The system breaks up the body into 19 segments, but it tracks 119 points to represent those segments, a count that keeps increasing as cameras and processing improve. (Don’t tell Old Hoss Radbourn, but the company plans to track fingers next season.) KinaTrax biomechanist Scott Coleman says there’s no reason why the company’s clients couldn’t quantify deception. “You could get super technical and … pick out … the key factors that go into this deception picture, and look at key 3, 4, and 5, and then come up with a metric and say, ‘OK, this guy’s deception is at this level.’ Basically a new stat, deception level.”

One front-office source estimates that roughly 20 teams have access to some sort of HPE system at their major league park or elsewhere. (All teams receive Statcast data, but rigorous biomechanical research requires a high-frame-rate feed that costs extra, and only some clubs subscribe.) But dissecting the dizzying amount of data produced by those systems, and collaborating across the different departments with expertise in this subject, can be daunting. “I think there are only a half-dozen teams that are trying to quantify deception and using HPE data to do so,” says one team quant. “And my guess is no more than half [of those] have done this reasonably well.”

Any team that thinks that it has figured out deception has incentive to keep that quiet, but Premier Pitching and Performance, a data-driven baseball training facility in St. Louis, recently lifted the lid on a first-pass pitcher deception stat. This summer, P3 used data from its Simi system to demo “expected deception,” a metric developed by R&D intern Ari Gordon that melds a deception potpourri—deviation from expected arm slot, “ball hidden ratio,” and extension—into a single stat. To assess ball-hiding ability, Gordon says, he “used the biomechanics data to determine whether the ball was hidden behind the body, head, or glove at each frame from peak lead leg lift until front foot plant, then divided the number of frames hidden by total frames within the time threshold.”

As an exploratory stat, expected deception depends on a number of assumptions and simplifications. But according to former P3 director of pitching Mitch Plassmeyer, who was hired in August as the University of Missouri baseball program’s director of player development, there seems to be some signal there. “It became pretty evident pretty quick with some of the guys that we quantified as higher deception that, yeah, these guys just do not get hit,” Plassmeyer says. “Their deception score’s high and they throw 90 and they just don’t get hit. … But some of these guys that throw 95 are low in deception, and they just get absolutely rocked.”

P3 has produced expected deception scores for about 120 college pitchers, but that total will climb as the facility continues conducting assessments with its partner schools. Plassmeyer expects the concept to catch on and be further refined by bleeding-edge college programs. “With all the new technology that’s available, I feel like if you’re not working on [deception] in some capacity in the background, you’re probably not doing as good of a job as you possibly could be,” he says.

Markerless motion-capture systems are still scarce and expensive, but a simpler, more accessible substitute exists. A company called ProPlayAI operates a mobile app and web portal, PitchAI, which allows players to upload open-side pitching video from smartphones or high-speed cameras. A machine-learning algorithm extrapolates from that side view to portray the delivery in 3D. Dr. Mike Sonne, ProPlayAI’s chief scientist, says the company is in the process of publishing a validation paper that shows that its accuracy is off by about 4 to 10 percent compared to a marker-based system.

PitchAI’s reports include a deception metric. “Our deception number is essentially, how many milliseconds does the hitter get to see the ball, from the moment of front foot strike to ball release,” Sonne says. In the PitchAI database, the average time visible is 65 milliseconds, with a 5th percentile value of 50 ms and a 95th percentile value of 95 ms. “I’m looking at the Statcast visualizer, and they have a value of 167 ms as the point where a hitter has to decide if they’re swinging or not, and a point of 100 ms being where the hitter can recognize the pitch,” Sonne says. “If a pitcher has a tell in their kinematics, you can see that this could add up to an additional 95 ms of information for the hitter, so I think there is most certainly something there.”

And that’s just the difference over a fraction of the full delivery. Hitters could potentially pick up information from the pitcher’s arm position even before the ball emerges from the glove like a rabbit from a magician’s hat. In the P3 sample, Gordon says, the average time from peak leg lift to foot plant is around 650 ms. Bottom-10 percentile pitchers from a ball-hiding standpoint block the ball with a body part for only 9 percent of that time, compared to 48 percent for top-10 percentile pitchers. The difference between those two groups in total time visible over that portion of the delivery is roughly equivalent to the time that the thrown ball is in the air.

The video below, based on PitchAI data, shows a high-visibility delivery, a low-visibility delivery, and then the two side by side, synced up and slowed down.

Like P3’s expected deception, PitchAI’s deception score is an experimental metric that thus far focuses on how the pitcher’s torso blocks the ball, without considering, say, the lead elbow. And like its more complex motion-capture cousins, PitchAI is still lacking a deception puzzle piece. “The big thing that’s missing from this modern motion capture data is information about where the batters are actually looking, and when they’re actually picking up the ball,” Buffi says. Analysts at facilities such as Driveline Baseball are conducting gaze-tracking studies that could fill in that blank, although there is one other catch: Markerless systems render pitchers’ joint segments, but not their full physical specifications. Maybe beefier bodies are better at hiding the ball.

Most of us will never know what it looks like—or perhaps just as important, what it doesn’t look like—to hit against Petit. But motion capture can provide at least a pale approximation. Asked for an example of a pivotal time when he thought deception made a difference, Petit flashes back to a crucial K in Game 1 of last year’s ALDS against the Astros. Petit entered in the fifth with the A’s trailing by one run, runners on first and second, and no outs. A three-pitch strikeout and two flyouts later, he’d stranded the runners and escaped the jam. The strikeout was the sweetest, because it came against Michael Brantley, a top-30 hitter since 2018. Brantley rarely strikes out, but against Petit he hardly seemed to see the ball.

Hawk-Eye’s skeletal tracking for that plate appearance was incomplete, but at The Ringer’s request, MLB’s video team put together a FieldVision animation of another high-leverage spot where Petit baffled Brantley, with a swinging strikeout this past May 18.

From the first time they take swings, hitters are told to keep their eyes on the ball. Against Petit, that’s impossible for just long enough to make even Brantley look bad.

As the industry reevaluates deception, Petit’s path to this point is potentially instructive. “I never threw hard,” he says. “So I had to prove myself.”

Like any pitcher who’s lasted so long, Petit has evolved to stay ahead of hitters. Over time, he’s traded some four-seamers for cutters and changeups, adjusted how he holds his glove before he starts his motion, and begun shifting on the rubber based on batter handedness to make himself less vulnerable to lefties. But to some degree, his ball-hiding ability has been with him from the start. “That’s my natural move,” he says.

“That thing that he does where he hides the ball with his body, he has had that since day one,” says former Mets scout Gregorio Machado, who signed the 16-year-old Petit as an amateur free agent in November 2001. Machado, through an interpreter, recalls that Petit pitched at the Twins’ academy in Venezuela for several weeks without getting signed. After a tip from Petit’s godfather, Machado brought Petit to Valencia, Venezuela, where he watched him for two weeks before signing him to a modest deal. Then, as now, he was throwing 85–88.

Coming up through the minors, Petit was a prospect because his results were so strong, but scouts still had reservations. “Statheads love Yusmeiro Petit, while traditionalists still can’t figure out why he is getting anyone out,” wrote minor league analyst John Sickels in 2005. In its 2004 Prospect Handbook, Baseball America had ranked Petit 28th in the Mets’ system, noting his “lack of a dominant pitch” but acknowledging that “he continued to leave hitters shaking their heads.” By the following spring, BA had elevated him to second in the Mets’ system. “Petit’s fastball leaves batters and scouts scratching their heads,” the book’s blurb read, adding that “nothing about it appears to be exceptional—except how hitters never seem to get a good swing against it.” BA quoted Brandon Moss expressing the same consternation that would one day be echoed by Pence, Andrus, and others: “I just can’t hit him. You just can’t pick the ball up off him.”

Entering 2006, Petit—who had been traded to the Marlins in the Carlos Delgado deal—ranked fifth in Florida’s system, and BA observed that he “continued to dominate in 2005 with a repertoire that’s typically deemed ordinary.” The Handbook conceded that his pitches played up because of his command and deception, and that some in the game graded his 88 to 90 mph fastball as plus “because of its movement and his ability to hide the ball well.” But both the 2005 and 2006 Handbooks relayed doubts that his stuff wouldn’t tie up higher-level hitters.

To be fair to the skeptics, Petit proved to be a below-average big league starter. After allowing 43 homers in 203 innings with the Diamondbacks, who acquired him from the Marlins in March 2007, he was selected off waivers and then twice released by the Mariners before spending 2010 and 2011 pitching in the minors, the Mexican League, and the Venezuelan Winter League. He didn’t really blossom until the Giants put him in the pen. It’s possible that Petit’s deceptive powers wear off with additional looks in quick succession: As a starter, he allowed a lifetime .613 OPS the first time he faced an opponent in a game, but that figure increased to .859 the second time through and .947 the third time through, both among the 30 worst figures of the wild-card era. (In relief, he hasn’t often gone long enough to face opponents a second time, but when he has, his OPS allowed has spiked from .655 to .873.)

Petit is probably in the right role for a pitcher with his talents, and he’s also probably on the right team. Oakland’s good defense gobbles up the balls his opponents put in play, while the Coliseum contains some of the flies that would leave other parks. Petit’s .250 BABIP is the lowest of the 192 pitchers who’ve thrown at least 400 frames since 2015. That’s partly a product of the fact that fly balls become hits less often than grounders, but it’s also a testament to the FIP-defying contact his pitches produce. “He gets a lot of weak contact,” Andrus says. “As an infielder, when you get a lot of weak ground balls, it’s always a great feeling. I don’t want those 110-mile-per-hour shots to me.”

This season, Petit’s hard-hit rate and average exit velocity allowed place him in the 96th and 90th percentiles, respectively, which has helped offset a 12.2 percent strikeout rate, one of the most minuscule in the sport. That’s disturbingly low even by Petit’s pitch-to-contact standards, and for anyone but Petit it would probably be disqualifying. The only other four pitchers with sub-13-percent strikeout rates have recorded a combined 6.61 ERA.

Petit’s track record of run prevention notwithstanding, concerns about pitch speeds and strikeouts have conspired to keep him in the price range of the penurious A’s and their low-velo, low-dollar, bullpen of misfit toys (which has faded down the stretch). Asked whether the market overvalues velocity, whether teams are too low on Petit’s ball-hiding ability, and whether his client would have landed a bigger deal had he posted the same or worse stats but thrown harder, Petit’s agent, Rafael Godoy, says “Yes to all above.” Granted, Godoy would be a bad agent if he’d said no. But it’s tough to come to any other conclusion, given that Petit signed a one-year, $2.5 million contract for this season after posting a 2.74 ERA in 289 innings over 240 appearances (which was tied for the major league lead) from 2017–20.

Even Machado, who saw something early in the slow-throwing Petit, is surprised by his success. “I didn’t think he would have the career he’s had,” Machado says. “I thought he could pitch in the big leagues someday because of his command and work ethic but never thought he would still be pitching at this level.” If ball hiding had a defined run value, would pitchers with instinctive deception be in greater demand? And could those who don’t have it be taught to borrow a page from the Petit playbook?

Machado believes the skill he spotted in Petit is even more liable to be missed amid the modern frenzy for speed. “You go to tryouts, and modern scouts are only looking for a 16-year-old pitcher that throws above 90,” he says. Emerson adds that the thirst for velocity sometimes backfires when it comes at a cost in deception. “You see a lot of hard throwers in the game [who are] working too much side to side, meaning that front shoulder’s rotated and bailed out just as that arm gets to the top, and now the hitter is able to track 97, 98 and you wonder, ‘How come this guy can’t pitch in the big leagues?’” The A’s try to teach pitchers to keep the ball behind their bodies, but young overthrowers can develop bad habits that are hard to break. Deception like Petit’s, Andrus says, is “something that you don’t see that too often now, because it’s all about velocity.”

However, there’s hope. “I know Yusmeiro does it in a natural way, but I think you can teach it,” Machado says. Petit’s teammate Deolis Guerra, who has a similar arsenal, says he’s gleaned a lot from Petit about reading hitters and inducing soft contact, which he’s excelled at this season for the first time. He’s also developed deception envy. “I need to learn how he does it and practice it,” Guerra says, adding, “It’s unbelievable. I think it’s something maybe you can learn with the years.”

Making deception more measurable could help player-development departments decide when to intervene and how to prioritize ball-hiding enhancements relative to other potential tweaks. “Does the guy have a lot of deception and is he having a lot of success?” Plassmeyer says. “Then you probably want to be very careful in your evaluation when you start to make changes or adjustments.” But if a pitcher’s struggles are backed up by poor deception, “then you can start to use it as a little bit of a training tool to teach that guy, maybe, how to hide the ball better without detracting from what he does well in terms of stuff.”

Petit’s durability and capacity to pitch in almost every other game may be partly a product of his ability to get by without the flaming fastballs in vogue today. “I think those types of arms don’t tend to last long, because they … practically get their arms exploded,” Machado says. Petit hasn’t been on the injured list since July 2009, which seems almost miraculous given rising injury rates. “I think that [lower velocity] has a lot to do with it,” Guerra says. “When you don’t throw as hard, it’s easier to recover.” It’s tempting to envision a team doubling down on deception and developing a fleet of Petits. “It would be new to systematically approach it, and the competitive edge is strongest when doing something positive that your opponents are not,” says historian, sabermetrician, and scout Craig R. Wright, the author of The Diamond Appraised.

A couple of caveats: First, Petit could be a unicorn, both in his feel for deception and in his hustle to be better. Teammates and coaches praise Petit’s preparation, unflappability, and personality, as well as his willingness to mentor and share wisdom with younger players. “This is one of the best humans,” Pence says. “I’m really thankful for the opportunity to have played with someone like him.” Guerra, who played with Petit in Valencia and Anaheim before joining him in Oakland, says, “The hard work he puts in every day, it’s unreal.”

Second, it’s not as if every pitcher could adopt Petit’s delivery without making some sacrifice in pitch quality. “Generally, when you tuck the arm behind the torso, it’s a little bit harder to create the bigger pitch shapes,” Bannister says. As one front-office analyst points out, “Pitchers who naturally lack deception might have optimized their deliveries toward other characteristics such as velocity, and there could be a trade-off that would exist if they tried to create deception.” The analyst adds that “If certain delivery patterns were found to create deception and became widely coached and adopted, then those patterns might in turn become less deceptive.”

It does help to throw hard, and any major league pitcher who doesn’t has to compensate somehow. Because it’s considered a prime suspect in any case of a curiously capable arm, deception is sometimes seen as the province of pitchers who need it to make up for some deficiency in speed, such as Petit, Jered Weaver, and Chris Young, or who don’t stand out in stuff, such as Sid Fernandez. “Sid had a conventional arsenal with a fairly pedestrian fastball, whose average velocity was within a single mile per hour of the norm,” says Wright. “His unusual effectiveness came from the fact that hitters picked up the ball so late. He tended to deliver his pitches in a manner where they came out of the backdrop of his uniform top.” Through his first 10 full seasons, from 1984 through 1993, Fernandez boasted the big leagues’ lowest hit rate and was one of baseball’s best bat missers.

In the big leagues, it’s likely true on the whole that soft-tossers are more deceptive than flamethrowers, because the former would have washed out without some smoke and mirrors. But it’s possible to be dirty and deceptive—to bring both da noise and da funk. Clayton Kershaw is deceptive. Max Scherzer is deceptive. Billy Wagner was deceptive. Deception doesn’t surface as often in discussions about dominant pitchers like that trio, because there’s so much to marvel at in their repertoires and radar readings. But their Hall of Fame (or Hall of Fame–caliber) careers point to the potential of pairing deception with stuff.

There’s something simultaneously exciting and deflating about the idea that deception is about to be solved. There’s not as much romance in a number on a stat site as there is in an unquantifiable final frontier. But there is a certain satisfaction in unraveling a mystery that’s gone unsolved for more than a century, and a justice to properly appreciating pitchers like Petit. Although they’ve long been barely more visible than the pitches they throw, the deceivers could be about to get their due. “You’ll start to see some of those pitchers pop up more often,” Plassmeyer says. “And it will be really, really good for the game.”

All stats through Sunday’s games. Thanks to Max Bay and Lucas Haupt for research assistance, and Octavio Hernández Pernía for interpretation assistance.