One of the great traditions of sports fandom is second-guessing the head coach. We do this for three reasons: First, as an emotional outlet after tough losses that require a scapegoat. Second, we’re all smart enough to know that we couldn’t throw 95 miles an hour or juke past an NFL linebacker, but what does that bum calling the shots do—stand in front of the bench and chew gum? I could do that job better!

Third, even good head coaches often make simple mistakes. For example: Andy Reid is a near-genius-level NFL head coach, but reading that made you throw up in your mouth a little, didn’t it? Because on one hand, you know Big Red has won 11 or more games nine times and made the playoffs 12 times in 18 full seasons, and he’s 16-2 coming off a bye. Give Andy Reid a quarterback who can run a little and two weeks to prepare, and he’ll beat the Cowboys, Patriots, or Ogedei Khan’s Mongol horde.

But on the other hand, you know that Reid’s clock-management shortcomings can only be described as a failure to learn basic arithmetic. And that’s frustrating—he does the hard stuff well but lets the easy stuff slip.

So too in baseball. There was a time when a manager could keep 25 testosterone-fueled egomaniacs—many of whom didn’t speak the same language—pointed in the same direction for six months, but couldn’t remember that bunting a runner from first to second with one out is a bad play. But for the better part of a decade, that hasn’t been the case—today’s managers are either smarter, more data-savvy, or more pliable than managers of the past, which means that by and large they don’t make the easily identifiable and mockable mistakes of the Tony La Russa era.

That is, until this season’s playoffs started.

In the past five years, playoff baseball has become a game of relievers—the 2012 Giants and 2014 and 2015 Royals had great success papering over their other weaknesses with deep bullpens. In 2014, Madison Bumgarner clinched a title with five scoreless relief innings in Game 7 of the World Series, and last year, the Indians got to within an inning of a title by starting Corey Kluber on three days’ rest routinely and having Andrew Miller suck up two innings in what seemed like every game.

These are not in and of themselves particularly innovative. Bumgarner’s performance in 2014 was analogous to Pedro Martínez’s in the 1999 ALDS, and CC Sabathia started on three days’ rest routinely down the stretch in 2008 and in the 2009 postseason. This year, however, we’ve crossed the Rubicon.

So far in 2017, 77 pitchers have made a relief appearance in the playoffs. Of those, 22 also started at least 10 games this year. Some of those 22 were moved to the bullpen for good at some point in the season, but seven of those 22—Justin Verlander, Chris Sale, José Quintana, Jon Lester, Lance McCullers, Robbie Ray, and Max Scherzer—have contributed at least one start and one relief appearance to the postseason cause, and with the exception of McCullers’s three-inning mop-up stint in Game 3 of the ALDS, all of their relief performances have come in an elimination game.

It’s becoming clear that after years of the one-inning closer’s role being stretched in the postseason, then obliterated by Cleveland in 2016, it took just 12 months for all traditional pitchers’ roles to follow suit. Because the playoffs are unique in intensity, schedule, and quality of competition, there’s simply no way to practice this, and managers are, understandably, having a hard time navigating this new frontier.

Managing a bullpen is much harder than it looks in a computer game. There is no fatigue meter—you can guess who’s at 100 percent, but you can’t really know beyond a shadow of a doubt. It takes time to warm pitchers up, and some—namely starters—take longer to get warm than others.

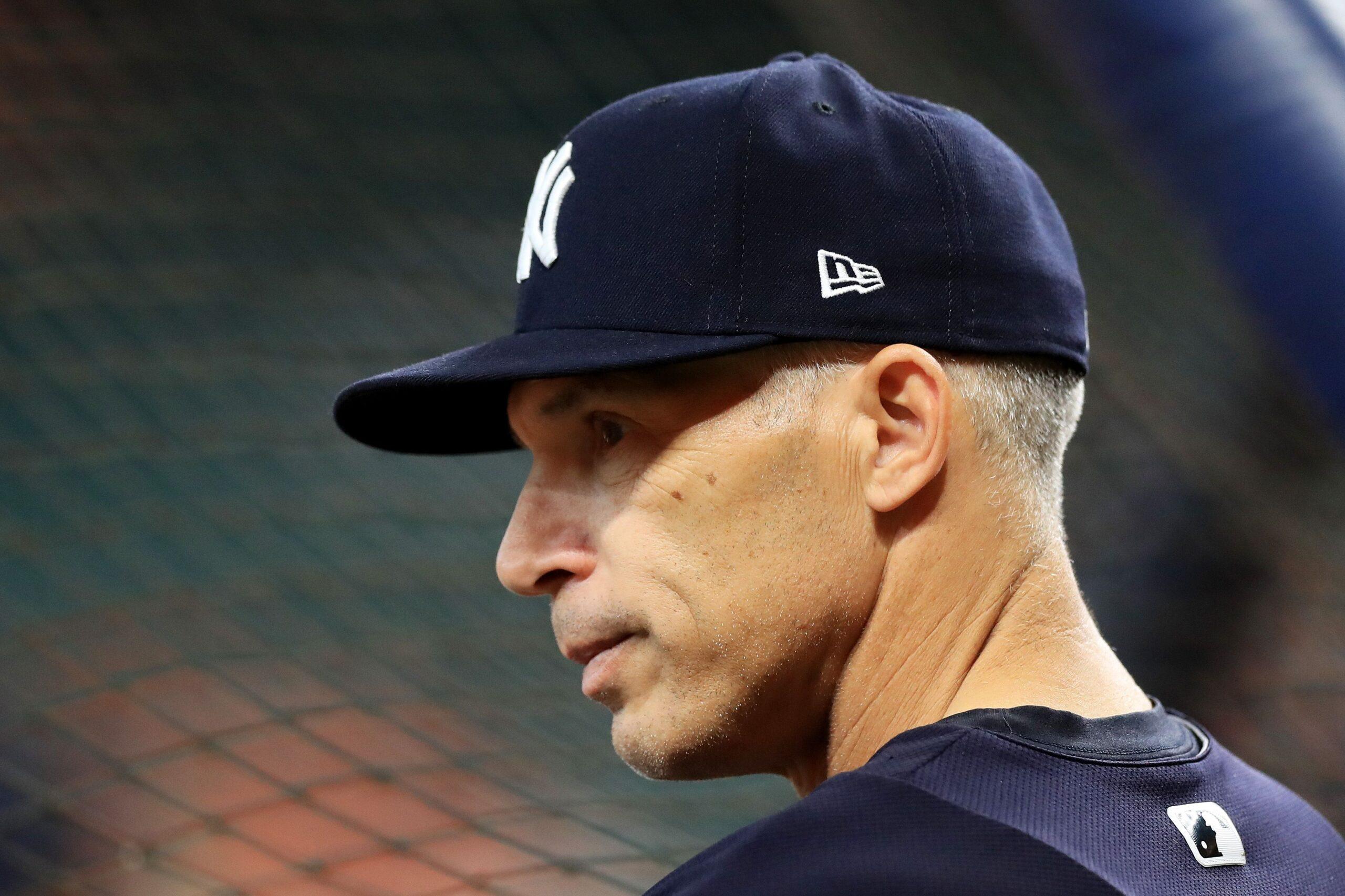

For example: Yankees manager Joe Girardi was trying to save his bullpen while up 8-0 in Game 3 of the ALCS, and gave Dellin Betances, whose battle with his command has become difficult to watch, a chance to show he could find the strike zone in a low-pressure environment. Betances walked two batters, and the man who replaced him was Tommy Kahnle, one of the Yankees’ high-leverage middle relievers. It would’ve made more sense to use starter Jordan Montgomery, who’s yet to throw an inning this postseason, but Montgomery would’ve taken longer to warm up than Kahnle. (Which, of course, raises the question of what exactly Montgomery is doing on the playoff roster if he won’t pitch while up eight runs in the ninth inning, but that’s an issue of roster construction, which isn’t completely on Girardi.)

The other major special consideration with using a starter out of the bullpen is that he usually isn’t used to coming in with runners on base, so it’s best to give him a clean inning to work with. This, along with the fact that short relievers don’t take as long to warm up, is why Ray and Rockies lefty Tyler Anderson entered at the start of an inning in the NL wild-card game, and why Sale and Scherzer got clean innings for their ALDS Game 4 and NLDS Game 5 appearances, respectively.

But managers don’t always follow this rule—when Verlander made his relief appearance in Game 4 of the ALDS in Boston, Will Harris was also warm in the Astros bullpen, but Houston manager A.J. Hinch went with his ace, even with a man on first, and Verlander gave up a go-ahead home run to the first batter he saw.

In addition to navigating the intricacies of starters coming out of the bullpen, there’s also the problem of running out of pitchers. Cubs manager Joe Maddon has flirted with running out of pitchers all postseason, and Joe Posnanski speculated that it might have been a lack of a better option, and not hubris or stupidity, that led Maddon to put John Lackey—a once-great postseason starter who’s at the stage of his career where he’s starting to grow lichens—in a position to give up the home run that ended Game 2 of the NLCS.

We knew this was difficult. What’s surprising is that this crop of managers in particular is having so much trouble. The four remaining managers—Maddon, Hinch, Girardi, and the Dodgers’ Dave Roberts—are four of the best managers in baseball. Arizona’s Torey Lovullo, who doesn’t have much of a track record as a first-year manager, would’ve gotten my vote for NL Manager of the Year, and his decision to use Ray for 34 pitches in a not-particularly-perilous middle-inning situation in the wild-card game, then bring him back on two days’ rest in Game 2 of the NLDS, might have resulted directly in Ray losing his command like Jason Neighborgall, with four walks, three wild pitches, and a hit batter in 4.1 innings.

Maybe the ease with which Terry Francona navigated this predicament last year skewed the curve, but this year, even Francona got burned by some of his more creative decisions.

Some things were out of Francona’s control. Kluber and Andrew Miller carried last year’s Indians to the World Series almost on their own, but Kluber was hit hard in both starts and Miller allowed his one home run of the playoffs at the worst possible time: late in a scoreless Game 3, which the Yankees went on to win 1-0. Injuries to Michael Brantley and Edwin Encarnación shortened Cleveland’s bench and played a part in Jason Kipnis, a second baseman since his college days, ending up in the unfamiliar confines of center field, where he was a defensive liability. However, Francona also screwed up some of the easy things: He spent one of his last six outs on Giovanny Urshela, who had a 44 OPS+ this year, for instance.

And Francona’s not the only one to stumble on problems that looked like they had easy solutions. John Farrell’s reputation as a manager is more mixed than some of the other managers in this postseason, but he won a World Series with Boston immediately after two years of intense clubhouse strife, so it’s not like he’s Gene Mauch. And Farrell started Deven Marrero (54 OPS+) over Rafael Devers (112 OPS+) at third base in Game 2 of the ALDS. Boston lost that game and then the series, and as a result, Farrell lost his job. And in all but the most charitable interpretations, Maddon’s trust in Lackey is another example of a manager tripping over his own feet.

Most notably, Girardi failed to challenge Lonnie Chisenhall’s hit-by-pitch that should’ve been an inning-ending strikeout, a decision which ultimately cost the Yankees Game 2 of the ALDS. Afterward, Girardi said he didn’t challenge because he didn’t want to break pitcher Chad Green out of his rhythm. Don’t take the easy stuff for granted.

Girardi delivered that ill-fated quote about Green’s rhythm in a postgame press conference, which starts with the losing manager moments after the game ends. On a night with a lot of traffic on the elevator, reporters have to hustle to get from the press box to the underground interview room before the press conference starts. There’s not much time, and having had more than five minutes to consider the game and look at tape, Girardi walked back his earlier comments the next day and admitted that he was wrong.

Immediately after Lackey coughed up Game 2 of the NLCS, Maddon said closer Wade Davis, three days removed from a 44-pitch, seven-out save, was available, but only in a save situation. The next day, given the same cooling-off period Girardi got, he deflected by joking about social media.

The two Joes are both well-regarded, both statistically curious and tactically creative, and both have a ring to show for their efforts as manager. But they’re stylistically different. Maddon is a career minor league coach with cool-guy glasses, a penchant for goofy motivational tactics, and a closet full of Eddie Vedder’s clothes.

The crew-cut Girardi had a 15-year MLB playing career and won his current job in part because he was Sufficiently Yankeeish. His first act as manager was one of shocking Yankees arrogance: The former Yankees catcher, who’d mostly worn no. 25 during four seasons in New York as a player and no. 52 during one year as the team’s bench coach, chose to wear no. 27.

“How many have they won?” Girardi said at his introductory press conference in 2007, meaning the 27th World Series title that had eluded the Yankees for the better part of a decade. When he won it two years later, he changed his number to 28.

Even though both managers could very well lose their respective series, the narrative surrounding them is heading in different directions. Maddon is losing his shine, while Girardi, after dodging a first-round sweep and evening up the series with Houston, looks about as safe as you can be in Yankee pinstripes. Some of that is the direction of their respective teams—Girardi has a young and up-and-coming club, while the Cubs are in the LCS for the third year in a row and expect a title every year now.

But some of it is how they’re handling their own mistakes. Ideally, a manager makes as few as possible, and when they do happen, they find a way to get away with them. Take, for instance, Roberts sending Yu Darvish to the plate in the sixth inning with the bases loaded, two out, and a chance to break Game 3 of the NLCS open, and Darvish drawing a four-pitch walk. But failing that, the best thing you can do is own up and learn from what went wrong, like Girardi did. This is a very difficult job, after all, and everyone makes mistakes. But acting like you’re never wrong makes it all the more embarrassing when you are.