After being part of one of the most iconic duos in sitcom history, Penny Marshall went on to make an even bigger mark. The Bronx native would become the first woman to direct a film that grossed over $100 million; she then became the first woman to direct two films that made over $100 million, while also becoming only the second woman ever to have a film nominated for Best Picture. Marshall was a trailblazer, and a larger-than-life character onscreen and off. On Tuesday, Marshall died at the age of 75 due to complications from diabetes. In her honor, The Ringer staff recalls her best work.

The Hall of Fame Scene, A League of Their Own

Marshall didn’t just direct A League of Their Own, she shepherded the movie along in every way, beginning from the time she saw a TV documentary about the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League and decided that it absolutely had to be a feature film. Inspired by the real-life stories of the ladies who played professional baseball during World War II, Marshall decided to conclude the movie with latter-day scenes set in Cooperstown (soundtracked by Madonna, which unfortunately makes it difficult to find on YouTube) that featured some truly inspired old-lady casting. Marshall also used as extras some of the actual athletes who had been a part of the league; the scenes of them playing baseball on Doubleday Field as the credits roll are “real,” and a testament to the fidelity that Marshall sought throughout the process. In her memoir, My Mother Was Nuts, Marshall noted that Steven Spielberg asked her how she accomplished the final scene:

“He was intrigued when I said that I used the real women,” she wrote. “‘They’re who I did the movie for,’ I said. ‘They’re who I wanted to honor.’ He asked if I would mind if he used that type of ending in his next film, Schindler’s List. I said, ‘Of course not. You’re entitled.’ And the truth was, it didn’t belong to me. In the same way that the end of Steven’s movie belonged to the survivors, mine belonged to all the women who had played the game.” — Katie Baker

Laverne DeFazio, Laverne & Shirley

She was a modern-day Lucille Ball, just bawdier and feistier, and with a big whompin’ Bronx accent even though the show was initially set in Milwaukee — and also by “modern-day” I mean “late ’50s as depicted in the late ’70s.” The zippy Happy Days spinoff Laverne & Shirley, a ratings blockbuster for much of its 1976–1983 run, had enough ribald physical comedy to qualify as a full-contact sport. And whether the sport in question was bowling or pro wrestling or short-order diner cooking or even kissing, Penny Marshall was up for it, with a big looping cursive L sewn right on her sweater, so that you knew she was Laverne.

If you needed her to somersault down a ramp in a debutante gown and take a bowl of punch to the face, she was game; her rapport with Cindy Williams’s Shirley was as natural onstage as it was tempestuous offstage, whether you pumped them full of nitrous oxide at the dentist’s or, why not, stuck them on giant coat hangers. Laverne & Shirley is not readily accessible in the streaming age, and it has aged the way you’d expect any ’50s-via-’70s sitcom to age. But the expertly awkward spectacle of Laverne dragging Richie Cunningham around a dance floor (and under her dress) is timeless. The show was more than its ecstatic and nonsensical theme song; Marshall would soon prove to be much more than just the show. But Laverne is a legacy to be proud of all her own, even at — especially at — her bawdiest. — Rob Harvilla

The Piano Scene, Big

It’s hard to know why a certain scene leaves an indelible mark on movie audiences. On one level, those two minutes in Big work functionally — they forge a friendship between Mac and Josh, who is soon after named vice president of product development. But they also make up a transcendent moment in a story that’s playing with the concepts of what it means to be a child and an adult. The piano, much like Josh, is larger than it should be. And yet its obscurity offers a platform of partnership, a time machine of sorts that renders a glaring age difference obsolete. How often do you get to see two premier actors dancing with such glee? Director Penny Marshall’s genius was capturing the moment with a wide shot, providing room to admire the skill involved with [Tom] Hanks’s and [Robert] Loggia’s movements. “It’s so organic,” says the movie’s cowriter and producer Gary Ross. “Once they try to play the duet of ‘Heart and Soul,’ they are inevitably in a dance routine together. It has an inevitable simplicity that makes it work.” — Jake Kring-Schreifels

The Master’s Wife, Hocus Pocus

Marshall’s uncredited role as The Master’s Wife in Hocus Pocus deserves its time in the spotlight. In her brief moments on screen, she memorably appears as the sassy-yet-tired wife to her real-life sibling Garry Marshall’s skeevy Devil, and together they’re hilarious and perfect.

In a movie rife with indelible performances — from the likes of Bette Midler, Sarah Jessica Parker, Kathy Najimy, and The Shape of Water’s amphibian man himself, Doug Jones — it’s the Marshall siblings’ scene-stealing cameo that stands out given their star power and the inside joke that they’re playing a married couple. And in her own right, Penny is impeccable as she doles out cheeky lines with her trademark stare, tinged with a mix of judgment, exasperation, and disinterest. That’s how you do a cameo. — Amelia Wedemeyer

Barbara, Portlandia

I’ve come to love the late period of comic legends’ careers, when their fans are grown enough to have their own shows to cast them for stunt cameos. (Think Carrie Fisher on 30 Rock, or in more of a cross-genre reinvention, Werner Herzog on Parks and Recreation.) In Penny Marshall’s case, this translated to a bit role in the 10th anniversary celebration of Portlandia’s Women and Women First bookstore alongside then–Trail Blazer LaMarcus Aldridge. As Barbara, the estranged frenemy of Fred Armisen’s Candace, Marshall plays a bed-sweater mogul who smacks her lips, nearly drives Candace to gas canister–based arson, and, most importantly, makes out with Armisen in drag. It’s silly, it’s pure, and after decades in the business, it’s what Penny Marshall deserved. — Alison Herman

The Preacher’s Wife (and Its Soundtrack)

The Preacher’s Wife was not Penny Marshall’s most successful film, nor was it her masterpiece (that’d be A League of Their Own and A League of Their Own, respectively). But it does feature: (a) Denzel Washington ice-skating, (b) good old-fashioned Christmas sentimentality, © Lionel Richie’s acting debut, and (d) a truly dynamite soundtrack, featuring one Whitney Houston. The Preacher’s Wife soundtrack was nominated for an Academy Award, and is the best-selling gospel album of all time. None of this changes the fact that (spoiler) Denzel and Whitney should have gotten together at the end of the movie, but at least we have the songs to remember them by. — Amanda Dobbins

“I Don’t Get It,” Big

Big is about a struggle between two men — Josh (Tom Hanks) and Paul (John Heard) — whose outlooks on life are diametrically opposed. Josh is carefree, joyful, and emotional, while Paul is repressed, rational, and conservative. The piano scene is iconic, and for good reason, but here Marshall boils the whole down to just under three minutes that shake out like a stage play. Paul represents the way things are, while Josh represents a strange, happier alternative. There’s a marked physical contrast between the two. On one hand, there’s the lanky, boyish Hanks, at the height of his comedic powers, pretending to be a child pretending to be a man. On the other, there’s the broad-shouldered, masculine, slightly beady-eyed Heard, playing the square for the millionth time in his career. Paul says things are so, or must be so, and Josh asks him the one question he wasn’t prepared for: Why?

The conflict between Josh and Paul, and their two outlooks, plays out through two other characters: Mr. MacMillan (Robert Loggia) and Susan (Elizabeth Perkins), and you can see the effects of asking why on their faces. Susan understands (perhaps better than the movie itself) that Paul has a point, that the structure of adult life is useful, and that Josh’s naive impetuousness is shocking. But Mr. MacMillan’s face tells you who’s going to win. Josh might be a kid, but he’s making Robert Loggia smile, soften up, and horse around. Eventually, Josh realizes that being a grown-up isn’t as fun as he dreamed it would be, which serves as a kind of half-hearted nod to the truth: that Paul might be a prick, but he has a point. But what you come away with from this scene is that the joy of childhood, expressed through Josh, is enough to melt the heart of Robert Loggia. What a powerful message that is. — Michael Baumann

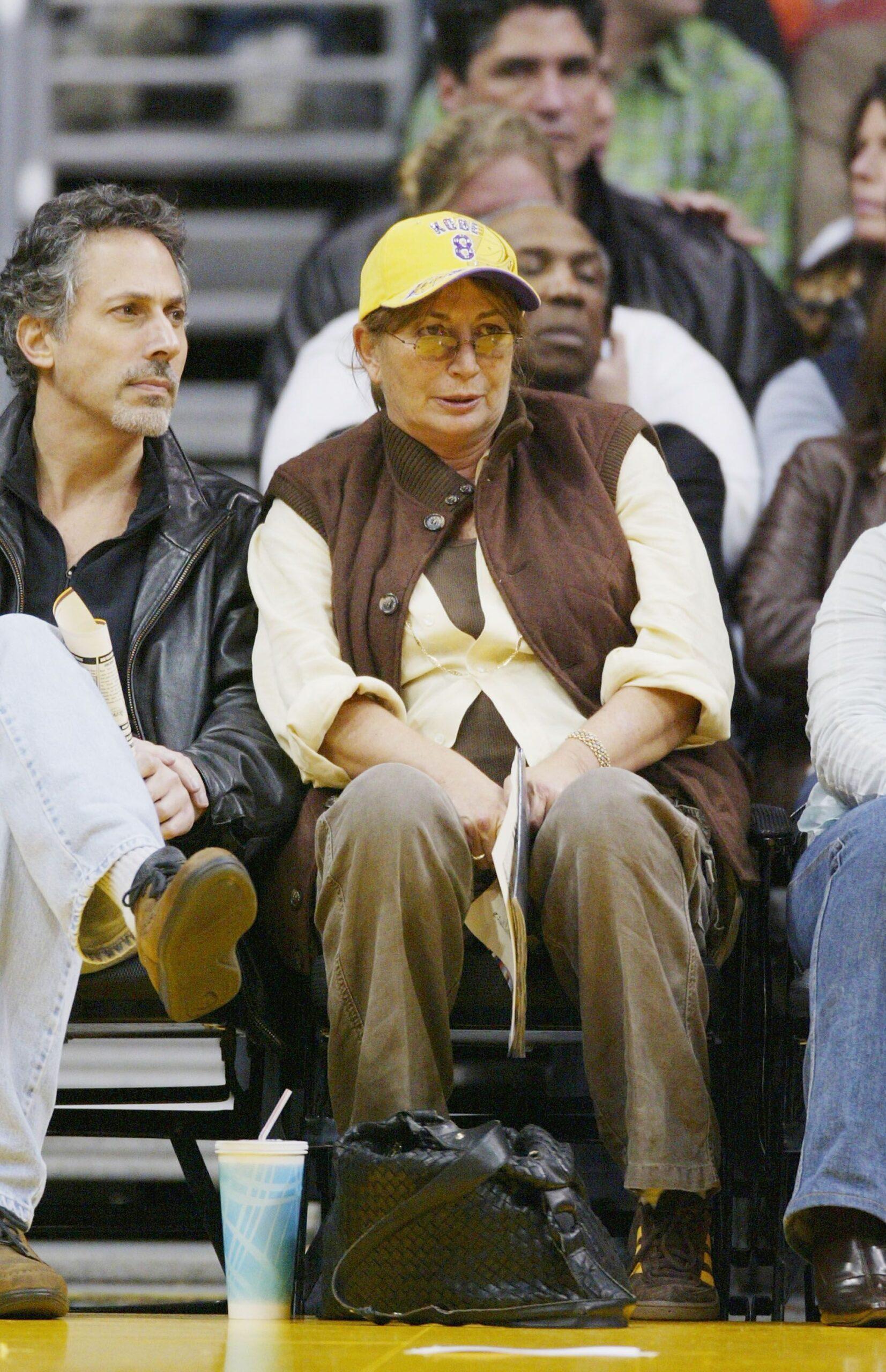

The Lakers Games

“My seats at the Staples Center became a second living room,” Marshall wrote in her 2012 memoir. Indeed, her residence at Lakers games was a sort of ritualistic lore that has embedded itself within the team’s culture; if Jack Nicholson was the president of the Lakers fan community, Marshall was the first lady. But where Jack often knew exactly how to make his presence felt — ask longtime refs how many times he’s berated them courtside, ask Staples Center employees working Christmas day games if they’ve ever gotten an unexpected holiday bonus from Saint Nich — Penny held her post like a stateswoman. “I went to enjoy games,” she wrote, “not run them.” It was a dignified presence that earned the respect of countless players over the eras, both the boom years and the rebuilding phases; she owned a Lakers championship ring, from their 2001–02 sweep of the New Jersey Nets, courtesy of Mitch Richmond, who closed out his career with a championship in his one season with the Lakers. It was a nod to seniority; he knew who the bigger Laker was. — Danny Chau