It wasn’t much more than a month ago that every baseball writer worth their words above replacement was playing the pace game with Mike Trout, who was then on track to break Babe Ruth’s record for the highest single-season WAR. But soon after the Trout WAR watch became one of baseball’s most-discussed stories, a nagging injury nudged the Angels center fielder’s season slightly off course. In mid-June, Trout suffered a strained right index finger that prevented him from playing center field for nine games and seems to have hampered his hitting even after his late-June return to the field. Over the 30 days before the All-Star break—which roughly coincides with the period since his finger started to bother him—Trout, who led the majors with 23 home runs through June 15, has slugged just .368 with two dingers (not counting his blast in the All-Star Game). Because Trout’s slumps are better than most hitters’ hot streaks, the increasingly selective superstar has still recorded a .466 on-base percentage over that span. Even so, he’s been worth only 1.0 WAR—a great month for most players, but a devastating one for a player in pursuit of Ruth.

Now that Trout’s previous 14-plus-WAR pace has ebbed to “only” 11-ish—which would still be the best mark of his incredible career—he may have a hard time fending off the field in the AL MVP race. As Trout has discovered in multiple previous seasons, a WAR lead alone is no guarantee of a first-place finish in the awards race for a player whose team doesn’t fare well in the pennant race. And as Trout’s Angels once again languish on the distant periphery of the playoff picture, his once-wide lead in the WAR race, like the Halos’ playoff odds, has dwindled to almost nothing.

At Baseball-Reference, Trout’s WAR edge has shrunk to two-tenths of a win. At FanGraphs, he’s locked in a three-way tie at the top. In both cases, the same three hitters are crowding him: Boston’s Mookie Betts and Cleveland’s José Ramírez and Francisco Lindor. Betts, who has the strongest claim to the title of baseball’s best non-Trout player, has been the highest-horsepower engine under the hood of what might be the best-ever Red Sox squad. But Ramírez and Lindor make for a remarkable combination, because the two sub-6-footers on the left side of the Indians infield are also doing something that the sport hasn’t seen since Ruth.

Ramirez, who’s hitting .302/.401/.628 with a tied-for-major-league-leading 29 homers, MLB-best baserunning value, and perhaps the best defense by a third baseman not named Matt Chapman, has accumulated 6.6 WAR at Baseball-Reference (6.5 at FanGraphs). Lindor, who’s slashed .291/.367/.562 while amassing the majors’ fourth-most defensive value, has recorded 5.6 WAR at Baseball-Reference (5.4 at FanGraphs). Put the two together, and the pair has produced a combined 12.2 bWAR through Cleveland’s first 95 games, which would extrapolate to 20.8 over a 162-game season.

Trout’s recent tail-off is the latest of many reminders that players on pace to achieve the extraordinary usually cool off (or heat up, depending on the record that they’re threatening to break). FanGraphs’ rest-of-season projections expect Ramírez and Lindor to add only 5.3 WAR to their current combined count. But even if those projections have the two players pegged perfectly, their resulting total of 17.5 WAR would top the tallies of some storied duos, including Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris’s sum in their own Ruth-chasing 1961 season (17.3). And if they can beat the projections by a modest amount, they’ll cement their status as among the most productive teammates ever.

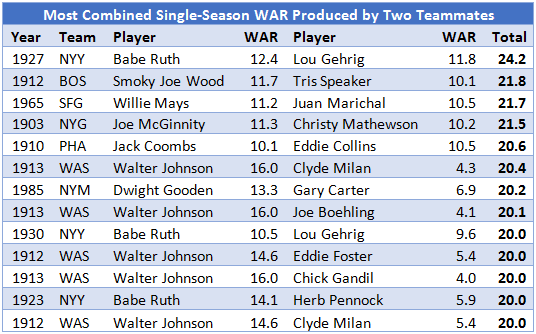

Nineteen of the top 20 two-teammate WAR totals in baseball history date from the 19th century, which makes sense considering both the era’s uneven competition and the eye-popping workloads that contemporary pitchers shouldered. (The full list is here.) The list-topping twosome of pitcher-outfielders Old Hoss Radbourn and Charlie Sweeney, who combined to accrue 26.4 WAR for the 1884 Providence Grays, accounted for 87 percent of that team’s innings—and Sweeney threw another 271 innings the same season for a different team. If we filter out the majors’ formative years and limit the sample to the sport’s modern era (1901-present), we get the table below.

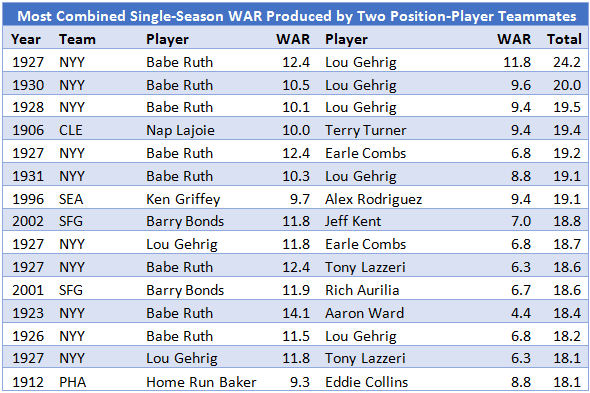

If Ramírez and Lindor stick to their extrapolated pace, they’ll surpass Jack Coombs and Eddie Collins for the fifth-best modern-era combo. But “modern” is a relative term: In 1910, Coombs pitched 353 innings, whereas last year’s innings leader, Chris Sale, finished short of 215. The upper reaches of the “modern era” leaderboard are still littered with pitchers whose workloads were extremely inflated by 2018 standards, so let’s filter further to tandems composed of position players alone.

Now the Cleveland duo’s potential total stands out even more. Their extrapolated total of 20.8 would put them second all-time behind the Babe and Lou Gehrig in their 1927 Murderer’s Row season. And if Ramírez and Lindor fall off their first-half pace but still outplay their projected WAR total by two wins, they’ll pull even with the best non-Ruth-Gehrig position-player combo—one formed, fittingly, by two other Cleveland infielders, Nap Lajoie and Terry Turner.

Although both Ramírez and Lindor have already nearly eclipsed their respective single-season WAR bests less than 60 percent of the way through the Indians’ season, neither All-Star is a one-season wonder. Depending on the source, Ramírez and Lindor rank either fourth and fifth or tied for fourth and sixth, respectively, among all position players in WAR since the start of 2016.

The 24-year-old Lindor, who appeared on prominent top-100-prospect lists for four springs running before making the majors in June 2015, has long been bound for stardom, and the elite defense that made up much of his value early on is now accompanied by one of the biggest bats at shortstop. Last season, he raised his fly-ball rate by 14 percentage points—easily the largest year-to-year increase among hitters who qualified for the batting title in both 2016 and 2017—which helped him add nearly 100 points to his isolated power and more than double his dinger total, from 15 to 33. This year, he’s retained most of those fly-ball gains and also become one of baseball’s best opposite-field hitters, posting a .400 isolated power on balls he’s hit in the air to the opposite field. That puts him in the 90th percentile among hitters with at least 25 oppo air balls in 2018, up from 25th and 27th in the past two seasons, respectively. Lindor, who hit three opposite-field homers from 2015 to 2017, has already doubled that total in the first half of 2018. His offensive explosion has helped propel what might be the best-ever offensive season by American League shortstops.

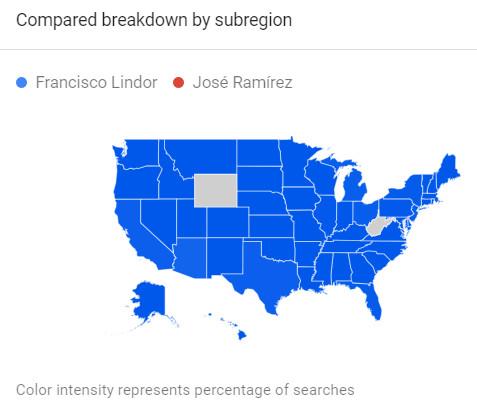

Ramírez, who has a shot at notching the most valuable season ever by a third baseman, is a little more than a year older than the ever-smiling Lindor, and although the stats say he’s been better, he still seems less well-known on a national level. There are several reasons that might be so: Unlike Lindor, he was never a rated prospect, and he didn’t become a good hitter until his fourth major league season, or a great one until his fifth. He didn’t settle in at a single position until this year, and because the Dominican native began learning English later than Lindor, he faces a language barrier when talking to non-Spanish-speaking media members. He also has a less distinctive name; excepting his September call-up in 2013, he’s had to share ownership with José Ramírez the middling major league pitcher.

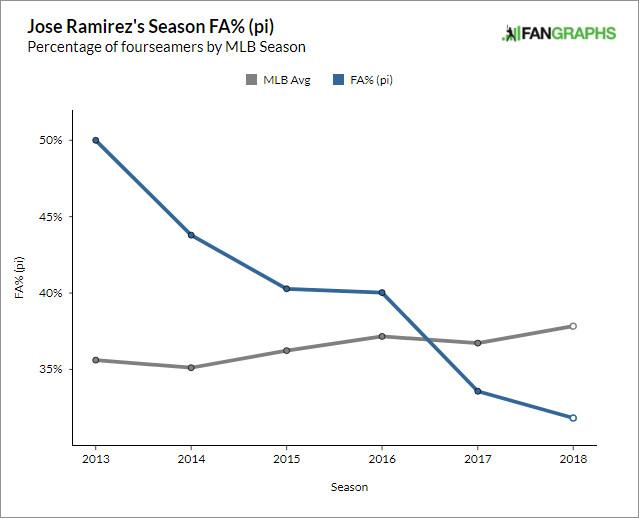

Like Lindor, Ramírez has dramatically improved his extra-base output. His 29 homers last season topped his combined total from 2013 to 2016 by 10, and he’s already matched that career high this season, pairing the power with his highest fly-ball rate and, for the first time in his big league career, more walks than strikeouts. If he can hold off J.D. Martinez, Trout, Aaron Judge, and Lindor, among other home-run-crown contenders, the 5-foot-9 Ramírez would be the shortest player to lead his league in home runs since Mel Ott in 1942—and the typical player has gotten a lot taller since then. Although many fans aren’t fully aware of his abilities, pitchers have learned to be, throwing him fastballs less frequently with each passing season.

With Lindor and Ramírez stationed at short and third, the Indians have allowed the league’s lowest batting average and weighted on-base average when right-handed opponents pull ground balls. And with the two 20-somethings ensconced in the first and third slots in the lineup, respectively, the Indians have outhit every team but the Yankees, Red Sox, Astros, and Cubs.

The only asterisk one could apply to Ramírez and Lindor’s potentially historic season is that the Indians have faced weak competition (albeit a whole heck of a lot stronger than the 1927 Yankees’ opponents). As I wrote last month, the 2018 AL Central looks like one of the worst divisions ever; in the time since that article was published, its historical ranking has improved from the worst of all time to merely the second-worst. The Indians’ strength of schedule to date has been weaker than that of any non–AL Central team, and no team has a weaker projected strength of schedule for the rest of the season. Of the 255 hitters with at least 200 plate appearances this season, Lindor and Ramírez have faced the second-worst and fourth-worst opposing pitchers in terms of 2018 results, as judged by a park-adjusted version of Baseball Prospectus’s advanced pitching metric, deserved run average.

Although both Baseball-Reference WAR and FanGraphs WAR include a league-strength adjustment, neither flavor of WAR accounts for a hitter’s quality of competition. “We account for competition on the pitching side, but have not done so on the batting side,” Baseball-Reference founder Sean Forman says via email. “If you watch the talk I gave at SABR last month, I actually list that as something we should strongly consider doing. The reason it hasn’t been a high priority is the assumption that it evens out in the long run, which is obviously not true in all cases.” An adjustment for quality of competition could also be complicated to implement accurately. “To do it right you would probably have to do something with projections,” adds FanGraphs founder David Appelman. “You can’t just take the in-season data and say, ‘That’s the competition.’”

Each additional layer of statistical abstraction (and potentially differing calculation across sites) erects another obstacle in the path of WAR’s mainstream acceptance; the more adjustments a metric makes, the more difficult it becomes to win over people who prefer to know what “did” happen rather than what would or should have happened after accounting for context. But philosophically speaking, adjusting for a player’s quality of competition doesn’t seem much different from adjusting for his ballpark, so it’s likely that the WARs will one day factor in players’ opponents; Appelman estimates that the difference might amount to “half a win-ish at the high end,” joking, “Lindor and Ramírez will still be pretty good.”

Baseball Prospectus is already taking steps to opponent-adjust its value metric, wins above replacement player. BP’s pitching WARP, which is based on DRA, already does account for competition quality (among many other factors). And early next month, BP will be publishing a new offensive stat called deserved runs created plus, which will look like Baseball-Reference’s OPS+ or FanGraphs’ wRC+ but, like DRA, will factor in a multitude of more granular influences that less complex metrics miss, including quality of competition, umpiring, catcher framing, pitch type and location, and even temperature. BP’s soon-to-be-published testing (which tends to be detailed and transparent) indicates that DRC+ is more reliable and predictive than existing offensive stats, according to the company.

Even though Ramírez and Lindor have benefited from facing weak pitching, they both rate well in BP’s forthcoming metric: Ramírez’s DRC+ (174) is identical to his wRC+, and Lindor’s DRC+ (138) is only slightly lower than his wRC+ (149). Whatever hit the two take because of opponent quality, they make up elsewhere: Both players will have higher values when WARP switches over to the DRC-based framework, likely because of kinder park adjustments or the new stat’s sensitivity to the value of walks.

In other words, even stats so cutting-edge that they aren’t yet publicly accessible can’t find fault with the two teammates who are carrying Cleveland to a division title and chasing the greatest position-playing tandems that the sport has ever seen. In Lindor and Ramírez, the Indians have two franchise players, both under team control through 2021 and both playing at the peak of their powers—or, perhaps, at what will look like their peak until they level up again.

Thanks to Dan Hirsch of The Baseball Gauge and Rob McQuown and Jonathan Judge of Baseball Prospectus for research assistance.