Seconds after the last out of an afternoon game on April 8, Fox Sports West reporter Alex Curry corralled Mike Trout in front of the home dugout at Angel Stadium and held a microphone up to his face. The Angels had just beaten the A’s 6-1 behind a brilliant start by Shohei Ohtani, and two of Curry’s three questions for the team’s star center fielder revolved around the rookie. “What’s it been like as a teammate to watch him dominate and exceed all expectations?” she asked. Trout fired off a few forgettable platitudes. “This morning Mike Scioscia compared Shohei to a young Mike Trout coming into the league,” Curry continued. “What has your relationship been like with Ohtani, helping him adjust to the big leagues?” Trout spouted several more clichés. Lastly, Curry cited the Angels’ 7-3 record in their first 10 games and inquired, “How fun has it been to see what this team is able to do?” Trout confirmed that winning was, in fact, fun, speaking at only slightly greater length than he does for his latest endorsement deal.

A fan tuning in for the conference in foul territory would not have known that Trout had contributed to the victory, too. In fact, he helped the Angels as much as any player not named Ohtani, going 2-for-3 with a home run, a walk, and a stolen base, driving in two runs and scoring two more, and catching a couple of balls in the outfield. But Curry shouldn’t be blamed for focusing on the big day by Ohtani, the two-way, 23-year-old phenom, at the expense of the one-way, 26-year-old Trout. Trout has been churning out multi-hit games with such great regularity since 2012 that it sometimes seems as if there’s not much more to say about his personal performance.

Which is why we have to guard ourselves against the temptation to focus on other faces for too long without also returning to Trout’s. Yes, Ohtani is exciting, and the Braves have called up top prospect Ronald Acuña, and Padres rookie Christian Villanueva has been the best hitter in baseball. Our eyes and ears are sensitive to change, and the sport always supplies someone new to demand our attention. That hype is healthy: We can make room in our hearts and minds for more than one major leaguer. But Trout has been the best for six seasons running, and now, not for the first time, he’s gotten better.

“We’re just witnessing him reach another level that we really didn’t know was there,” Angels GM Billy Eppler, who inherited Trout when the Angels hired him in October 2015, told me Tuesday, adding, “His experience and his maturity are helping him reach new levels of overall offensive contribution.” That sounds like a far-fetched claim to make about a player who already had a whole level to himself, but in Trout’s case, it’s true.

A few hours after I talked to Eppler, Trout launched his major-league-leading 10th homer (and also walked twice) in the Angels’ one-run win over the division-rival Astros. That pivotal performance extended one of the hottest stretches of Trout’s career, which has featured many more hot streaks than slumps.

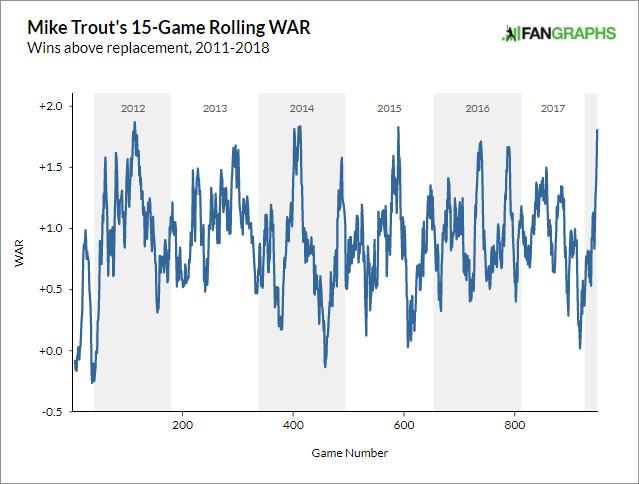

Trout’s latest, greatest season had an inauspicious start: On Opening Day, he went 0-for-6, a career first for him. In the Angels’ second game, Trout hit a homer, restoring order, but his ascent wasn’t uninterrupted: Just prior to his postgame comments on April 8, he went 19 consecutive plate appearances without a hit. Since April 8, though, Trout has hit .396./.507/.887 in 15 games, producing 1.8 wins above replacement, as much as he has amassed in any 15-game span since the summer of 2012.

Since his opening oh-fer, Trout has hit .329/.442/.741, raising his full-season wRC+ to 200—twice as productive as an average hitter. That offensive outburst has helped him vault him to the top of the 2018 WAR leaderboards at both Baseball-Reference and FanGraphs. Injury absences and minuscule samples aside, Trout has been a fixture at the top of every value leaderboard since his first full season, so he’s no stranger to periods of intensely impressive performance. Unless he stays on a tear in the Angels’ final four games in April, this probably won’t be his best calendar month at the plate: In July 2012, he hit .392/.455/.804 in 25 games, and in July 2015, he hit .367/.462/.861 with 12 dingers in 21 games. But the way he’s generating his offensive value in 2018 is different than ever before and may portend a peak year at the plate.

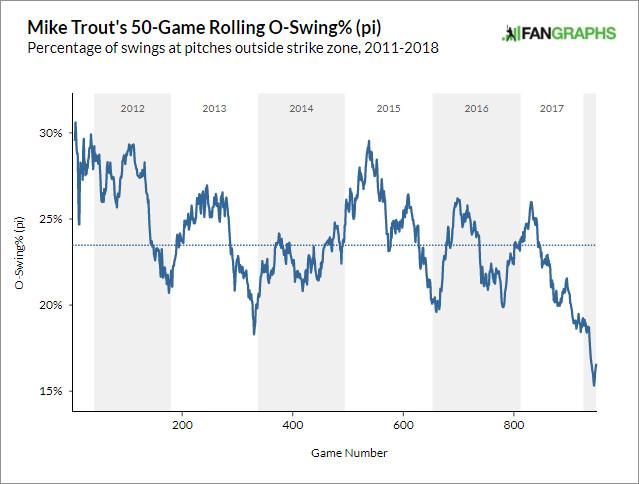

Stop me if this sounds familiar: Early last season, I wrote about how Trout was hitting better than ever. His improvements come like clockwork, and the thesis was true then, too: Although the torn thumb ligament he suffered less than two weeks after that May 2017 article kept him from reaching his customary range of eight to 10 WAR, he did finish with his highest seasonal wRC+. Last year I noted that the key for Trout was an increased tendency to swing at pitches inside the strike zone. This season, he’s still swinging at those pitches, but he’s also stopped swinging at pitches outside the strike zone. Only two qualified hitters have chased less often than Trout.

Over the course of his career, Trout has produced a .471 weighted on-base average on in-zone pitches and a .242 wOBA on out-of-zone pitches. Swinging more often at the former has made him much more dangerous as his career has progressed, and because he’s now cut down dramatically on his swings at pitches outside the strike zone, pitchers have been forced to throw the ball over the plate: Among qualified hitters, only the unimposing quartet of Carlos Asuaje, Aledmys Díaz, Kole Calhoun, and Howie Kendrick have seen a higher percentage of pitches in the zone this year. As the typical hitter has seen fewer pitches in the strike zone, then, Trout has seen more pitches in the strike zone than at any point since 2012, when the league wasn’t yet aware of how good he would be. And because Trout is Trout, he’s punished pitchers for daring to challenge him, setting up an almost Bondsian “pick your poison” dilemma for opposing arms.

Last year, I published a table of Trout’s year-by-year ratios of zone swings to out-of-zone swings, a proxy for “selective aggression,” the highly desirable ability to attack hittable pitches and leave the others alone. Aside from his brief debut season, Trout has always been a great hitter, but he hasn’t always had an elite sense of the strike zone. However, he’s gained a greater command of the zone with each passing season, save for a slight step back in 2015, when he probably played through a wrist injury. The last column in the updated table below shows Trout’s yearly percentile ranks in selective aggression among qualified hitters.

Mike Trout’s Selective Aggression by Year

Trout’s selective aggression is now in the 98th percentile. It’s impossible to be much better than that. Many hitters improve their plate discipline as they age, but few do so as dramatically as Trout. The GIF below compares heat maps of Trout’s swing percentages by pitch location in 2012 and 2018. The 2018 image features deeper blues (signifying fewer swings) outside the strike zone and darker reds (meaning more swings) inside the zone.

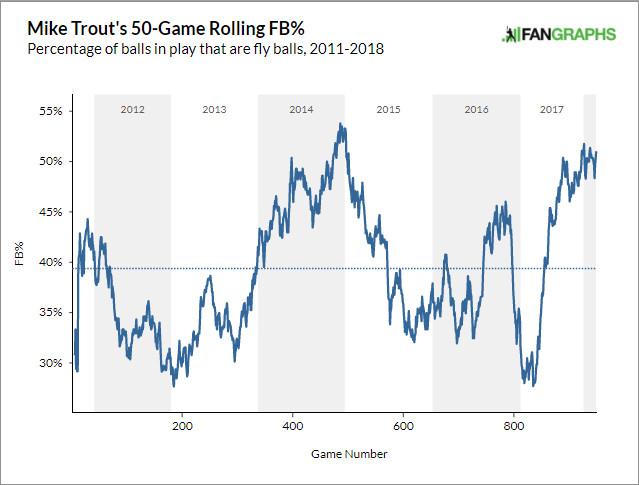

Trout’s tightened grasp on when to swing and when to take has contributed to a higher average exit speed than he recorded in 2016 or 2017 and his highest average launch angle in the three-plus-season Statcast era. Only in the second half of 2014 did Trout hit fly balls as frequently as he has in recent games.

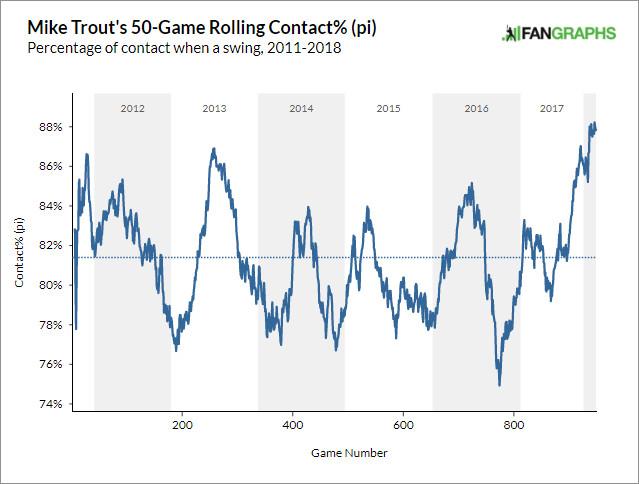

In 2014, Trout’s power came with less contact, a typical trade-off: He hit 36 homers, which tied for fourth in the season just before the juiced ball arrived, but he also led the American League with 184 strikeouts. This year, Trout has produced an MLB-leading home run total while striking out significantly less than the league as a whole and making more contact than ever.

In spring training, when Trout went weeks without whiffing, both he and Angels assistant hitting coach Paul Sorrento said that he wasn’t consciously doing anything different. His latest improvement seems instinctive and experiential. “As crazy as it sounds,” Sorrento said in March, “I don’t think he’s tapped his full potential, really. He’s getting older. He’s getting smarter at the plate. He’s got a better concept of the pitches he can and can’t handle, which is really very few. I think he’s just evolving, getting better and better every year.”

Although Trout is, as one FiveThirtyEight piece put it, “outrageously consistent at being outrageously great,” his ability to maintain a sizable separation from every other player season after season stems from his continued commitment to eliminating any whisper of weakness from his game. A few years ago, he got better at hitting high fastballs, which had briefly been his bugaboo. He also grew more comfortable hitting with two strikes and became less passive against 0-0 pitches. Dissatisfied with his sinking stolen-base totals after 2015, he decided to steal more, and he accomplished his goal. In Trout’s first three-plus seasons, his arm was 11 runs worse than the average center fielder’s, according to defensive runs saved. Struggling at something—even something that cost his team only a few runs a year—displeased Trout, so he set his mind to being more of a throwing threat. Sure enough, in the three-plus seasons since, his arm has been worth one run more than the average center fielder’s. This spring Trout resolved to improve his overall defense, which advanced metrics haven’t loved lately. And according to Statcast, he’s been two outs above average in the outfield so far, up from three and two outs below average in the past two seasons, respectively.

When Trout got hurt last season, I lamented the lost chance at a career year by a player who’s likely to end up as an all-time great. Maybe I needn’t have bothered, because 2018 is looking like the season that 2017 was on track to be. In 2013, when Trout was robbed of a rightful AL MVP award for the second time, his supporters pointed out that while Miguel Cabrera had been a better hitter, Trout’s value in the field and on the bases more than made up for the difference in offense. If 2018 Trout could be teleported back to 2013, that argument might retroactively be rendered unnecessary. Trout’s offense is approaching “2013 Cabrera” territory, and he’s still an all-around star.

Eppler noted that Trout “has a ton of open-mindedness,” and that despite his success, he still works regularly with Sorrento and lead hitting coach Eric Hinske. “Sometimes it’s maintenance, and sometimes it’s a little bit more specific, something that Mike’s feeling or Mike’s recognizing,” Eppler said. On occasion, Eppler has texted information to his hitters, providing advice about pitches to target or lay off of. When I asked him if he texts advice to Trout, he laughed. “We text a lot, but not generally about hitting,” he said. As riveting as Ohtani is, Trout is the Angel who’s still dominating and exceeding the highest expectations in the sport.