For the second season in a row, Cleveland has entered the summer months in a bit of a rut. Though manager Terry Francona’s crew is in first place in the feeble AL Central, its 32-28 record places it well behind the AL’s top clubs, and it’s unlikely that another record-setting win streak is waiting for Cleveland this August, too. Thus far in 2018, Cleveland’s lineup has scuffled beyond the top of the order and the team has suffered its share of injuries, but an ultimately mediocre run prevention unit has been the main culprit behind this start. That component designation is even more of a surprise than the teamwide troubles, as Cleveland’s 2017 pitching staff might have been the best in MLB history. The 2018 version, despite returning nearly all of last season’s key pieces, ranks just 18th in ERA.

The rotation is not to blame, however, even if Houston’s staff has usurped it as a potentially historic group. Corey Kluber leads all pitchers in bWAR; Trevor Bauer is spinning a 2.77 ERA when he’s not feuding with that Astros group on Twitter; Mike Clevinger has taken a giant, if funky, step forward as a starter; and Carlos Carrasco is struggling relative to his own expectations but still boasts an above-average park-adjusted ERA. Overall, Cleveland ranks third in starter WAR, and that’s with erstwhile fifth starter Josh Tomlin suffering the worst home run season in MLB history.

The relievers have diverged from the rotation, though, and after a year characterized by impressive bullpen depth, Cleveland’s relievers have fallen to the league’s bullpen depths. They rank last in ERA (5.93), second to last in both Baseball-Reference’s and FanGraphs’ versions of WAR, and last by a large margin in home run rate allowed. They rate poorly by advanced numbers, ranking 27th in win probability added a year after placing second, and they rate poorly by standard numbers, ranking last in win percentage with a 5-13 record. The bullpen shouldn’t be this bad going forward, but the current picture is mighty bleak.

Those numbers encompass two broad issues with the Cleveland bullpen: The star arms have lost some of their luster, and the complementary arms have receded from confident to shaky. Francona revolutionized modern reliever deployment in 2016 with Cody Allen and Andrew Miller, but neither reliever has pitched to his previous level thus far in 2018.

Allen’s main problem has been a degradation of his swing-and-miss ability, which stands out especially given the ongoing leaguewide rise in strikeouts. Among 23 relievers with at least 10 saves, Allen ranks just 15th in strikeout percentage; last year, he ranked 11th out of 40 such closers in K rate.

Miller, meanwhile, has experienced an across-the-board decline: His hard-hit rate is way up, his strikeout rate—though still an enviable 34.9 percent—is his lowest since 2012, and he’s walking his highest rate of batters since he became a reliever. His current stat line resembles that of Dellin Betances during the Yankee righthander’s down periods.

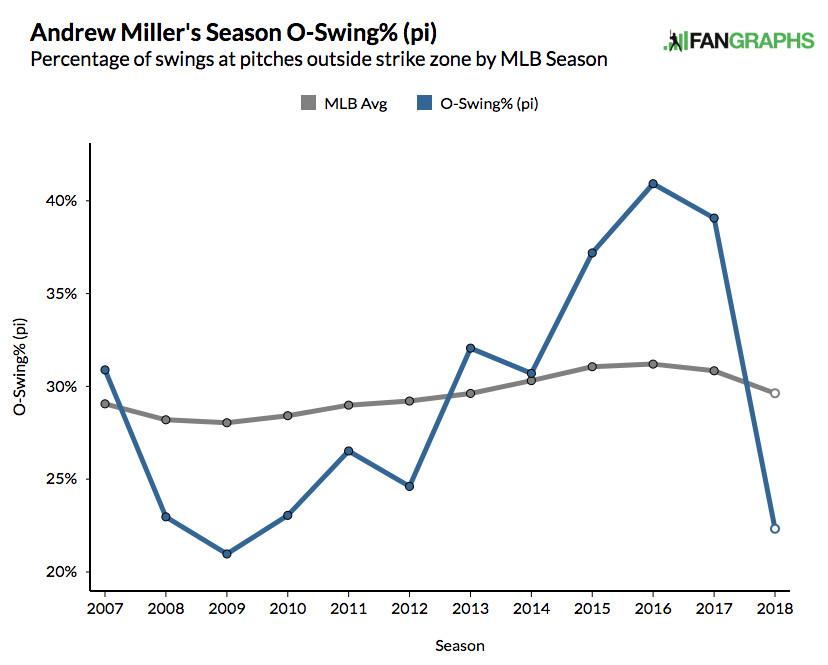

At his peak, Miller excelled at tricking hitters into swinging at the wrong pitches: He generated a high proportion of swings at would-be balls while fooling hitters into taking a high proportion of would-be called strikes. A total of 915 pitchers threw at least 10 combined innings from 2015 to 2017; Miller ranked first in his induced ratio of swings on pitches outside the zone to swings on pitches inside the zone. Miller’s problem is that his chase rate has plummeted; among 442 pitchers with at least 10 innings this year, he ranks just 264th in that ratio. The sudden decline forms a striking visual, as Miller has regressed all the way to his pre-relief days in this area.

That change has had a particularly deleterious impact on his vaunted slider, which from 2015 to 2017 was one of the most effective in the sport. By FanGraphs’ pitch values, Miller’s was the fifth-most-valuable slider in that span—and because that stat is cumulative, he was the only reliever in the top 10. But his slider has been a below-average pitch in 2018, as opposing batters have hit .286 and slugged .514 against it; last year, they were down at .097 and .133, respectively.

These issues likely stem from Miller’s myriad injury problems. Beginning in late April, he missed two weeks with a hamstring strain, then allowed seven runs in 4 1/3 innings upon returning from the disabled list before heading back on the shelf. His current injury—right knee inflammation—afflicts the same body part that necessitated two trips to the DL last season, and although Miller is slated to return sometime this month, the persistent nature of his leg troubles casts some doubt about his ability to return to and sustain his 2016 form going forward.

Miller’s combination of absence and ineffectiveness has only exacerbated the rest of the pen’s problems, which extend beyond the eighth and ninth innings. The bullpen was so loaded last year that Cleveland left Dan Otero, Nick Goody, and Zach McAllister off its playoff roster, even though all three relievers posted ERAs below 3. This season, Oliver Pérez, who has thrown all of 2 2/3 shutout innings, is the only reliever with an ERA below 3, and Allen (3.76) is the only other reliever with a mark below 4.

Otero’s ERA has ballooned to 6.97, Goody’s to 6.94 before he was hurt, and McAllister’s to 6.45, and the trio’s peripherals are all just as bad as those totals suggest. Lefty Tyler Olson, at least, has somewhat better underlying numbers, but after not allowing a run in 20 innings last year, the fact that his 2018 ERA also starts with a 6 is plenty reason for pessimism. Stalwart Bryan Shaw is gone—though his current 6.89 ERA in Colorado would slot right in to Cleveland’s current group—as is 2017 trade deadline acquisition Joe Smith, but those losses alone don’t explain the penwide unreliability at Progressive Field.

One summative statistical comparison encapsulates the extent of Cleveland’s year-over-year relieving collapse. On last season’s team, 20 players pitched for Cleveland and just one—Kyle Crockett, who allowed two runs in 1 2/3 innings—finished with a negative WAR total. In the wild-card era, only three other teams (including this year’s Red Sox) have so ably avoided negative pitching contributions. Among Cleveland’s 21 pitchers thus far in 2018, though, 13 have been below replacement level—a total worse than that of only three last-place teams (Padres, Marlins, and Reds).

Concern over a likely playoff team’s bullpen is an annual baseball rite, and fortunately for Cleveland, general bullpen capriciousness makes this issue the easiest to address. Just last season, the Nationals finished the first half with the worst relief ERA in the majors (5.20) and ranked 26th in relief WPA (minus-1.72 wins). But after the All-Star break, and after Washington added Sean Doolittle, Ryan Madson, and Brandon Kintzler in trades, the Nationals’ bullpen ranked seventh in ERA (3.54) and first in WPA (plus-6.23 wins).

Cleveland has the pieces for a similar turnaround in 2018. They’re starting from a better position than those Nationals, for one, because they at least have stronger arms at the back end; Allen and Miller could bounce back to solidify the end game, and odds are that someone from the middle relief corps will stop allowing homers like he’s pitching in Coors Field in the ’90s.

Moreover, premium relievers like Kelvin Herrera, Brad Hand, and Zach Britton—if healthy—should be available at the trade deadline, and even secondary arms would present a meaningful upgrade over the current crop of Cleveland relievers. In the high-velocity, high-strikeout era, there is no shortage of effective, tradeable relievers; the likely-to-sell Padres alone have five, including Hand, who have thrown more than 20 innings with an ERA below 3.

Cleveland ultimately needs a bullpen upgrade or three, but it also has the luxury of remaining patient and not forcing an imbalanced deal just because its demand is high. It has the majors’ easiest schedule the rest of the way, and its four division mates are all projected to finish with losing records, so Cleveland is already, in essence, gearing up for another postseason run. We know that when that postseason run occurs, Francona will want a flexible, dependable bullpen; at the moment, he has precisely zero healthy relievers who fit that profile, but his tactics aren’t doomed. Cleveland has four more months of injury rehabilitation, in-house experimentation, and trade exploration until the relief corps casts real concern over their title hopes. After all, only one bullpen in the post-1961 expansion era—the 2007 Devil Rays’—has finished a season with an ERA north of 6, and on pure talent alone, Cleveland is unlikely to nudge up against that mark all year long. Skill reveals itself in time, so there’s no reason to panic even as bullpen losses mount.