The Astros don’t look like they did a year ago. They’re still one of baseball’s best teams, of course, with a 21-15 record and plus-63 run differential that ranks second in the majors, and they have the best projected rest-of-season record according to both FanGraphs and Baseball Prospectus. But they’re succeeding because of a different part of the roster than last season.

In 2017, the World Series-winning Astros were led by their lineup: Their offense last year was the best since the Murderer’s Row Yankees, and they ranked second among 2017 teams in home runs. In 2018, though, despite returning all of their useful batters, they’ve sent just a league-average offense to the plate and rank 18th in homers. Reigning MVP José Altuve (two homers, one stolen base) is, at the moment, baseball’s best singles hitter rather than his typical power-and-speed threat; Marwin González (89 wRC+) and Jake Marisnick (23 wRC+) have lost all the offensive gains they made last year; and Evan Gattis (54 wRC+) hasn’t hit at all.

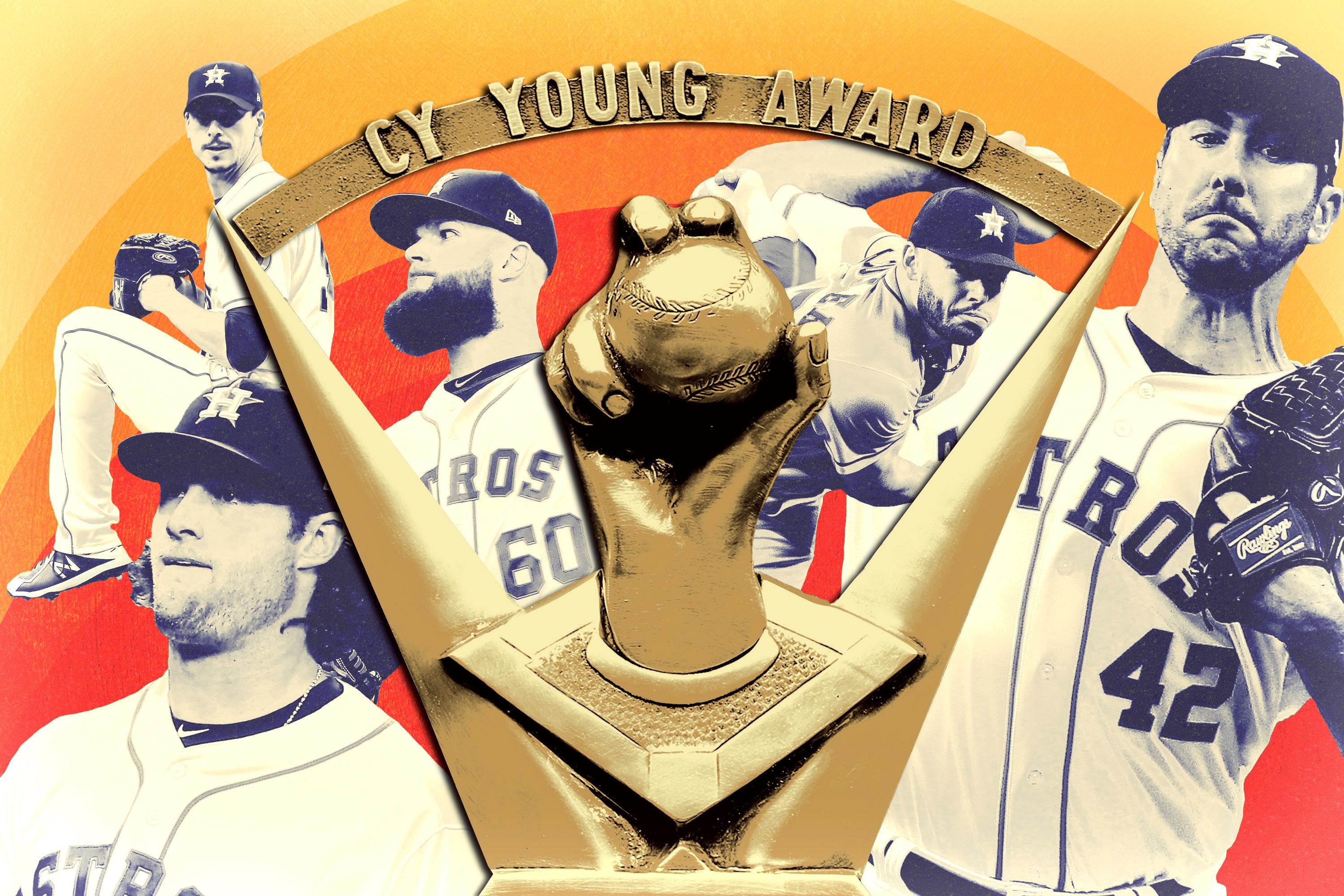

But a different segment of Houston’s roster is compensating for the offensive regression, and the Astros’ rotation is thriving. Recent MLB seasons featured pitching staffs that deserved some level of “best ever” recognition: The 2017 Indians had the best-ever group of pitchers by FanGraphs’ version of wins above replacement; the 2016 Cubs had the best rotation since the deadball era by park- and league-adjusted ERA; the 2011 Phillies had the best rotation ever by park- and league-adjusted FIP. The 2018 Astros, so far, are on pace to eclipse all of those groups. Houston’s starters are pitching like the newest, and most superior, best rotation ever.

That standing starts with two pitchers who joined the club within the past nine months: Gerrit Cole and Justin Verlander, who rank no. 1 and no. 3, respectively, in FanGraphs pitching WAR so far. Last week, The Ringer’s Michael Baumann spoke to Cole and wrote about the former no. 1 pick fulfilling his potential, and in Cole’s only start since that article’s publication, he struck out 16 Diamondbacks and allowed one hit in a complete-game shutout. His last pitch of that game was a 99.3 mile-per-hour fastball—the fastest Cole has thrown this season. By game score, a metric designed to judge the quality of a start in a single number, it was one of the 15 best nine-inning starts in history.

From the moment the Astros acquired Cole in January, in exchange for four of Houston’s fungible depth pieces, the trade seemed like the steal of the offseason, and that was before the former Pirate transformed into a version of Craig Kimbrel who can pitch nine innings at a time—the new Astro’s current strikeout rate of 41.9 percent would set a single-season record, while Kimbrel owns the sport’s highest career K rate at 41.9 percent. In Cole’s worst start of the season (three runs allowed in 6 2/3 innings against Oakland), he still struck out 12 and didn’t walk a batter.

Verlander, meanwhile, has already won an MVP and a Cy Young, yet he’s off to a personal-best pace in his age-35 season, a full four years after he allowed the most earned runs in the AL. His strikeout and walk rates are at career bests, and his 1.17 ERA ranks second among qualified starters. That number will fall back to the pack, surely, as his tremendous luck with batted balls falling into gloves and runners staying stranded on the bases diminishes, but since coming to Houston at the end of last August, Verlander has a 1.13 ERA in 13 regular-season starts and a 2.21 ERA in six postseason appearances. It’s hard to nitpick such a dominant profile.

Beyond Cole and Verlander, the Astros rotation features three more pitchers with impressive credentials. Dallas Keuchel (3.98 ERA) has pitched the worst of the bunch, and he’s a recent Cy Young winner with a better-than-average ERA. Lance McCullers (3.73 ERA) is in line with his career averages across the board, which means he’s the same tantalizingly talented pitcher he’s always been, and capable of rebounding from a clunker (eight runs and six walks in 3 2/3 innings against Minnesota on April 11) with a three-start stretch in which he allows just two runs across 20 innings. And Charlie Morton (2.16 ERA), World Series Game 7 hero, has evidently continued to throw harder, to the point that only Luis Severino and Noah Syndergaard have a higher average fastball velocity among starters (Cole ranks fifth).

Taken together, that group has produced an outrageous, unprecedented set of numbers through the first month and change of the MLB season. Through Saturday, each of Houston’s five starting pitchers had completed seven starts; in those 35 games, the Astros rotation posted a combined 30.7 percent strikeout rate and 2.41 ERA. The only qualified starters in league history to exceed a 30 percent strikeout rate while dipping below a 2.50 ERA in a season are Randy Johnson (five times), Pedro Martínez (four), Clayton Kershaw (two), Chris Sale, and Corey Kluber. Even accounting for the league-wide increase in strikeout rate, that’s a remarkable, restrictive group of comps.

We should expect those numbers to regress, of course—particularly the ERA, which has been buoyed staff-wide by an abnormally high strand rate—but the underlying data behind those surface statistics are inarguable. By expected weighted on-base average (xwOBA), which estimates what a team’s level of production should have been based on batted-ball data like exit velocity and launch angle, the Astros’ starters rank as the league’s best by such a large margin that the second-place Dodgers are as close to 10th place as they are to Houston. And that ranking isn’t solely an effect of Houston’s penchant for strikeouts; the Astros place first in xwOBA on contact, too.

And let’s not let calls of small sample size ruin the appreciation of Houston’s accomplishment thus far, either. While it’s too early to project the Astros to, say, definitively set the record for best park- and league-adjusted ERA in MLB team history (which they’re currently managing by a wide margin), it’s not too early to compare what the Astros have done to great seasons by individual pitchers. Houston’s 35 starts through Saturday are about where the league leader typically resides at season’s end (that number was 34 last season, but to account for Houston’s entire rotation pitching an equal number of games, it’s easiest to use Houston’s first 35 here). So by way of comparing Houston’s 2018 rotation to the best individual pitchers from last season, the Astros’ starters have a:

- 30.7 percent strikeout rate. Among qualified starters last year, only Chris Sale, Max Scherzer, Corey Kluber, and Robbie Ray did better.

- 23.8 percent strikeout-minus-walk rate. Only Sale, Kluber, Scherzer, and Clayton Kershaw did better last season.

- 2.41 ERA. Only Kluber and Kershaw did better.

- .188 batting average allowed. Only Scherzer did better.

- .574 OPS allowed. Only Kluber and Scherzer did better.

- 0.95 WHIP. Only Kluber and Scherzer did better. (Kershaw did the same.)

- Total of 224 innings pitched. No pitcher did better. (Chris Sale led the majors with 214 1/3.)

- Value of 6.1 wins above replacement. Only Sale and Kluber did better.

Let’s imagine a hypothetical in which a single pitcher—let’s call him Orbit—posted the same statistics the Astros staff has over 35 games through a full season. Orbit would be a top-five pitcher by K% and K-BB% and a top-three hurler by ERA and opponent batting line; he’d pitch the most innings and post a top-three WAR total. His combination of strikeout prowess and stingy run prevention would match that of only two Hall of Famers, Kershaw, Sale, and Kluber in all of MLB history. Orbit would win the Cy Young, or come darn close.

It’s inherently silly to suggest that the whole Astros rotation is worthy of a Cy Young award, in a manner reminiscent of the Atlanta Hawks’ entire starting five winning Player of the Month honors for January 2015, when the team went 17-0. The collective honor was “reflective of all the work our entire team and organization has put in,” Atlanta coach Mike Budenholzer said at the time. The Astros starters haven’t gone undefeated, but the same sentiment applies: Cole and Verlander have led the way, but it’s been a group effort with no weak links. There couldn’t have been any, given the unprecedented numbers Houston’s rotation has put forth.

And even if that group needs to fold in a new member or two due to injury at some point this season—every one of Houston’s starters has required a visit to the disabled list within the past three years; Morton has gone at least once every season since 2012—Houston has the depth to maintain its run prevention and strikeout successes. The Astros’ replacement starters would be Brad Peacock, who has a 2.63 ERA and 30.4 percent strikeout rate in relief, and Collin McHugh, who has been even better with a 0.68 ERA and 36.5 percent K rate, also out of the bullpen. Houston’s roster includes seven starters who are better than the seven best starters from the rest of the AL West combined, and the comparison isn’t particularly competitive.

As recently as last season’s August 31 waiver trade deadline, Houston’s rotation was a point of concern alongside a historically dominant offense. Before the Verlander trade, the rotation was talented but tenuous; between last season’s All-Star break and the end of August, the Astros ranked just 19th in the majors in starter ERA. McCullers and Keuchel were alternately inconsistent and injured, and Morton hadn’t yet completed his evolution into a star. Now, McCullers and Keuchel are effectively no. 4 and 5 arms, even if they’d be the clear ace on other teams, and the historical dominance in Houston emanates from the mound rather than the batter’s box.