In the season finale of Pluribus, Carol Sturka learns a lesson she’d inadvertently imparted to others throughout the show’s first eight episodes: Free thinkers are sometimes insufferable. After Manousos Oviedo completes his pilgrimage to Carol’s cul-de-sac, he pierces her carefully constructed romantasy story about an exclusive, committed relationship with Zosia, starts experimenting on the Others, and presses Carol to help him. But instead of renewing her efforts to undo the Joining, Carol quickly aligns herself with the hivemind and skips town, giving Manousos the silent treatment that the Others once inflicted on her. Globetrotting and sightseeing ensue. But the idyllic, delusional interlude ends during a disconcerting après-ski exchange, in which Zosia inadvertently reveals that the Others are taking a new tack in their quest to convert Carol to their hivemind—and that they’re closing in on what they would consider a cure to her individuality.

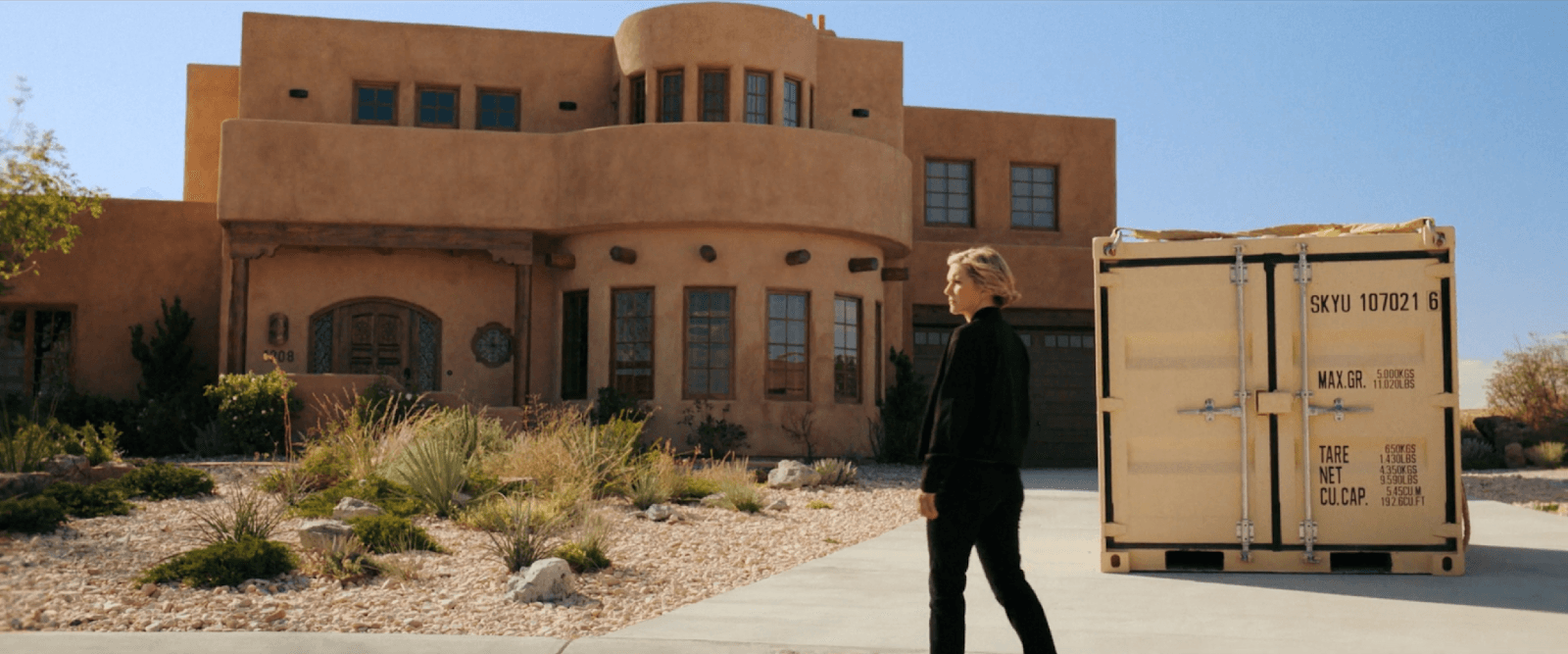

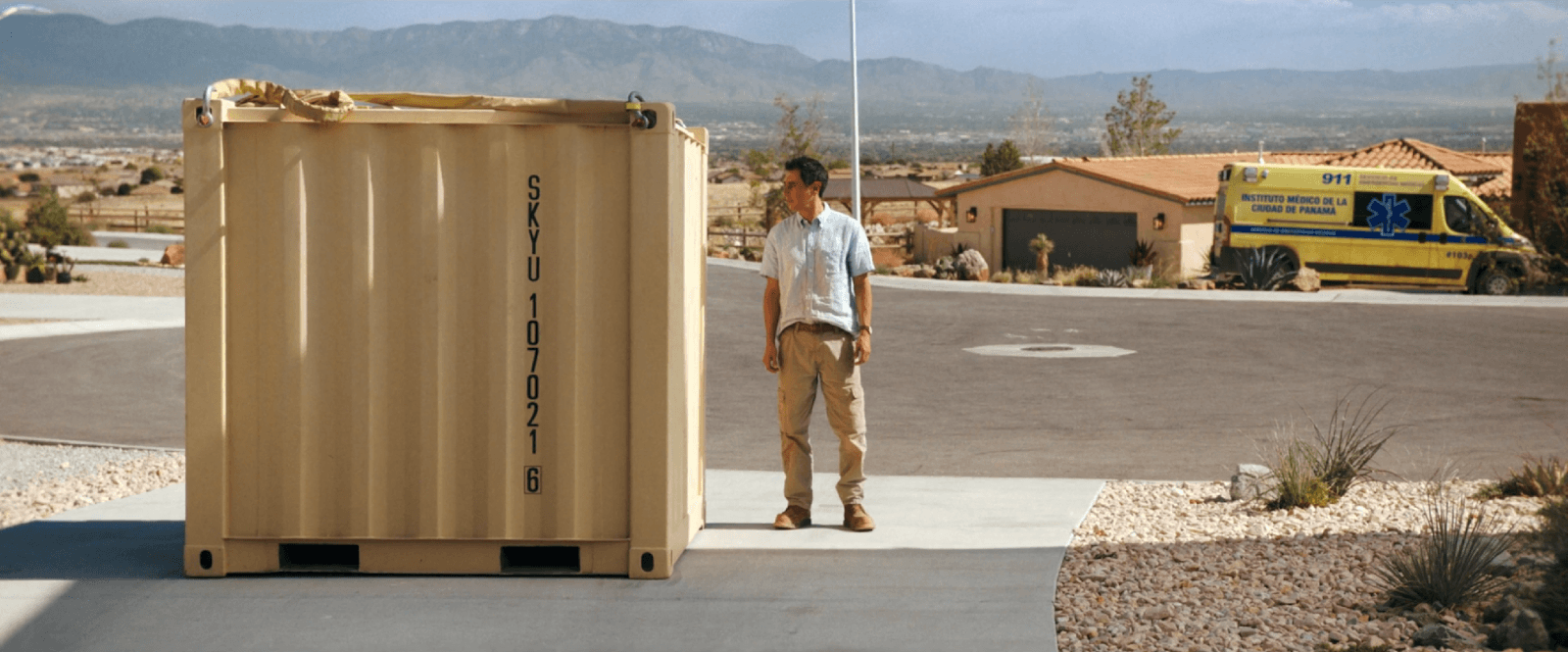

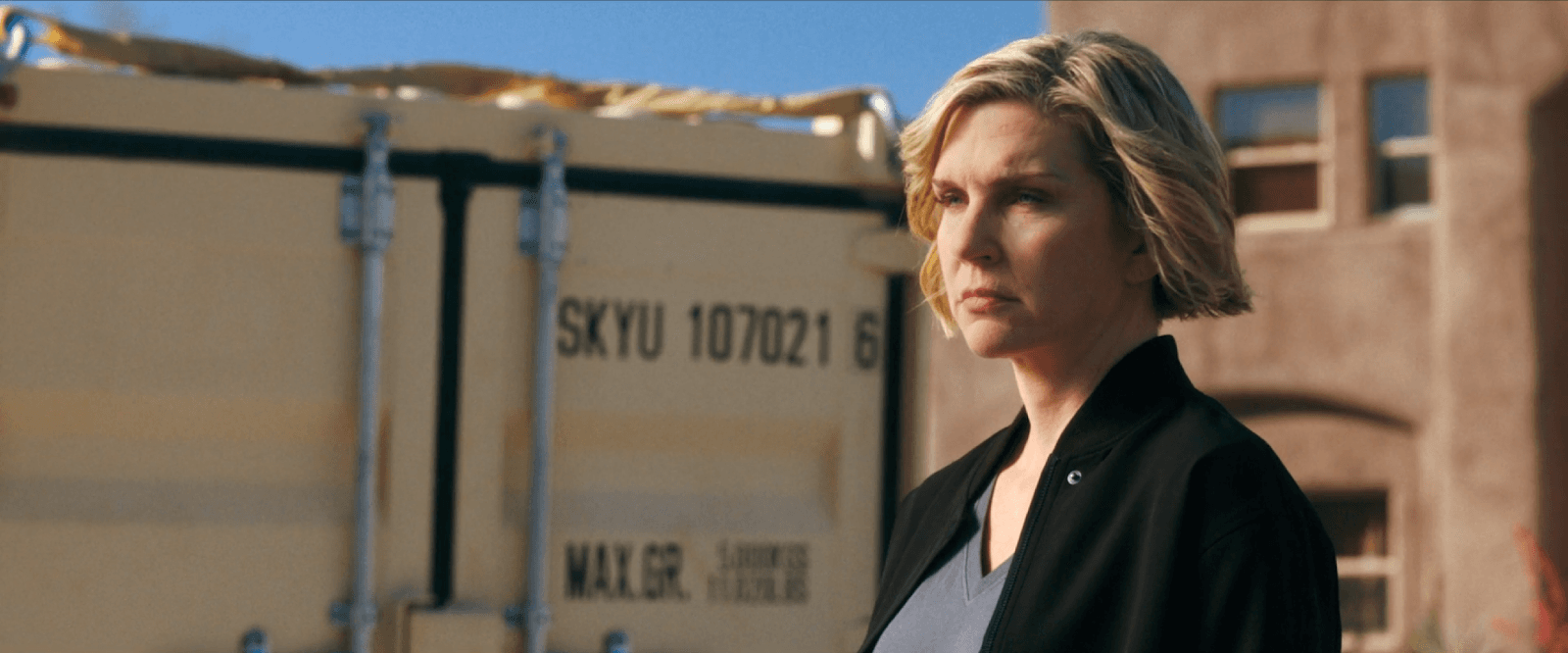

And so Carol cuts the quasi-honeymoon short and returns to 1208 Cielo Rosado Court, in a helicopter piloted by her (presumptive) ex. (Awkward—but functionally equivalent to hitching a ride with any of the several billion other entities Carol also kind of dated.) The helo is hauling something else: a big ol’ cargo container. The natural question is one best expressed by Detective David Mills: What’s in the box?

For less than three minutes, it’s a mystery—a literal mystery box. But almost immediately, the mystery is solved.

“What is it?” Manousos asks.

“Atom bomb,” Carol answers, matter-of-factly.

Thus, Season 1 ends not with a bang, but with the potential for one—and with one last Sturka-esque eff you to the TV practice of keeping viewers in the dark while drip-feeding fans tantalizing tidbits of plot. The finale makes the series’ rejection of the medium’s mystery-box structure explicit, but Pluribus has turned its back on the concept since the start.

Pluribus is sometimes described as a mystery box, and there’s not much mystery about why. It’s a high-concept, big-budget, sci-fi series, and many mystery-box shows tend to fit into that framework. Its creator, Vince Gilligan, started out on one of the formative mystery-box shows, The X-Files. And the secretive and, yes, mysterious marketing of the show in the months leading up to the premier primed people to view Pluribus as a puzzle. The inscrutable teasers seemed like mini-mystery boxes themselves.

Once the show aired, though, it became clear why Pluribus had kept its cards close to the vest prior to the premiere: It was planning to lay them all out on the table in Episode 1. Compare the Pluribus premiere to, for instance, Lost’s: Both were riveting, but the latter raised many more questions than viewers might have had coming in, whereas the former settled much of the uncertainty. The opening act of Pluribus not only established the series’ premise, but it also explained the origins and implications of the predicament Carol finds herself in. When a startled Carol realized at the end of “We Is Us” that government official Davis Taffler, as an emissary of the Others, was on TV talking to her and telling her whatever she wanted to know, her experience and bewilderment mirrored those of Pluribus watchers, who weren’t accustomed to transparency from a show of this kind. Genre fans are used to being strung along.

“Mystery is the catalyst for imagination,” J.J. Abrams declared in his original formulation of the mystery-box concept. Consequently, he explained, “there are times when mystery is more important than knowledge,” which in turn justifies “the withholding of information,” on purpose, for greater engagement. That model might dictate that Pluribus maintain the mystery of the box’s contents into Season 2. Instead, the series simply says, Nope; it’s a nuke—and, by the way, we told you to expect one in Episode 3.

Revealing the warhead doesn’t disarm its explosive capabilities, either as a weapon or as a narrative device. If anything, the disclosure deepens the suspense and engenders a more substantive sort of speculation. Instead of simply questioning what, we’re wondering why, how, and when.

“I don’t think Pluribus is a mystery-box show,” Gilligan told Vulture after the finale, dispensing some wisdom he acquired while working on X-Files mythology episodes: “An ongoing mystery in a show that is indefinite versus finite, that is the hardest kind of show to do. You see that with X-Files, you see that with Lost. If you’re trying to go forever and you have an ongoing mystery—even before X-Files, I remember loving Twin Peaks and then went, Wait a minute, are we ever going to get answers for this thing?”

“The lesson I learned is not how to do a better mystery-box show. The lesson I learned: Don’t do a mystery-box show. You may already know everything you need to know about Pluribus, in terms of mystery.”

The best example of Pluribus’s resolute stance against mystery for mystery’s sake is the way it explains the virus that makes humanity into a collective. This may be first contact, but it isn’t Contact; the fateful signal from afar isn’t sending instructions for interstellar travel. As Taffler tells Carol in Episode 1, the broadcast is coming from such a vast distance (600 light years) that “There's no telling how long it’s been repeating. Maybe throughout all of human existence.” In Episode 8, we (and Carol) learn the actual source of the signal: a planet called Kepler-22b. “So, what are the people like on Kepler-22b?”, Carol asks Zosia, who responds, “We’ll probably never learn the first thing about them. They’re too far away.”

This is somewhat realistic, as alien-related sci-fi scenarios go—if we ever do discover evidence of intelligent life, it’ll probably be too far away to talk to—but it’s also a clear indication of Pluribus’s priorities. The Keplerites’ motivations may be indecipherable—for all we know, Kepler-22b’s inhabitants didn’t design the signal, but received it and turned their planet into a glorified wireless repeater, as the Others are trying to do on Earth—but regardless, they don’t much matter.

We don’t know what Gilligan has up his sleeve for the next three or so seasons—even he has only a loose idea—so maybe Colonists from Kepler-22b will eventually land after all. But so far, the series has actively downplayed that possibility. The sci-fi material is merely a means to an end: Like the alien system itself, it’s a mechanism for bringing about the desired conditions. Although there’s a wide range of opinions on what Pluribus is “about,” it’s crafted to be a thought-provoking character study more so than a plot-delivery device.

As Ringer contributor Joshua Rivera wrote about Paradise for Slate, “What we’re really talking about here is the difference between a show’s writers directly withholding information from the viewer and a show’s characters withholding information from each other. Both are viable storytelling techniques, but the latter is always going to be more satisfying for the way that it invites the audience to participate.” With the basics clarified and spectators’ curiosity about those aspects of the story slaked (or, at least, strongly discouraged), Pluribus can prompt us to ponder what we would do in Carol’s stead, how we would value the competing virtues of harmony and self-determination, what life would be like with much less suffering but also a lot less surprise, and other weighty ideas.

The biggest surprise Pluribus has in store is the way it subverts the viewer’s priors re: the rhythms of serialized streaming TV. “We are all attuned to the ebb and flow of a mystery box type show, or movie,” Gilligan observed to Alan Sepinwall, writing for The Ringer. “We’ve all seen our share of M. Night Shyamalan movies or Twilight Zone episodes where there’s a great twist. We are attuned to that, we expect it. Sometimes, the best twist is no twist.”

Pluribus stubbornly resists the twist. In dystopian thriller Soylent Green, the shocking epiphany that civilization runs on nutrients from human bodies precipitates the end of the film. In Pluribus, it precipitates … the end of Episode 5. And when Carol shares her new knowledge with Koumba in Episode 6, she learns that the Others already told him, and that he essentially accepts their “other other white meat” meal replacement. Nobody’s being murdered, and although the nonviolent cannibalism is disquieting, it follows from what we already know about the Others. The discovery doesn’t dictate Carol’s actions, either; in fact, she grows closer to the Others after finding out about “HDP.”

Unlike a liquid diet fortified by human remains, mystery-box storytelling tends not to be nourishing, in the long run. The dopamine rush that accompanies each pellet of plot is unfailingly followed by the frustration of a narrative rug pull that sustains the story (and, by extension, the series). And each successive bombshell has a lower payload. As Gilligan elaborated to Vulture, “These great M. Night Shyamalan twists you see? That works best if you’ve got an hour and a half. Doing that in an indefinite TV show, I don’t know how you pull that off. It’s architecturally unsound. It collapses under its own weight.”

Pluribus, by contrast, rests on a solid story foundation. There’s no DHARMA Initiative or Lumon Industries to serve as a cryptic antagonist. There’s just the hivemind, which has been fairly up front about its needs and desires (if not always fully forthcoming about its methods).

Now, in fairness to well-made mystery-box shows: The initial sugar rush is real. Lost was riveting until the appearance of a grand plan fell apart. Pluribus isn’t appointment viewing in the same sense: it’s a more contemplative, and less propulsive, sort of series. Pluribus, Sepinwall writes, has “invited more speculation than Gilligan’s other series, as viewers keep trying to read nefarious motives into the Others’ actions, even though we know they are pathologically honest.” (Unlike the Others on Lost.)

That’s probably a recipe for short-term disappointment. Chekhov’s nuke may be sitting outside Carol’s house, but Hitchcock’s “bomb under the table” analogy barely applies to Pluribus, which rarely lets us see something Carol can’t. Complaints about the quiet parts of Pluribus, or the pace of its plot, may stem from a misconception about what type of TV it is, but for both better and worse, it’s unquestionably a slower burn than its mystery-box brethren.

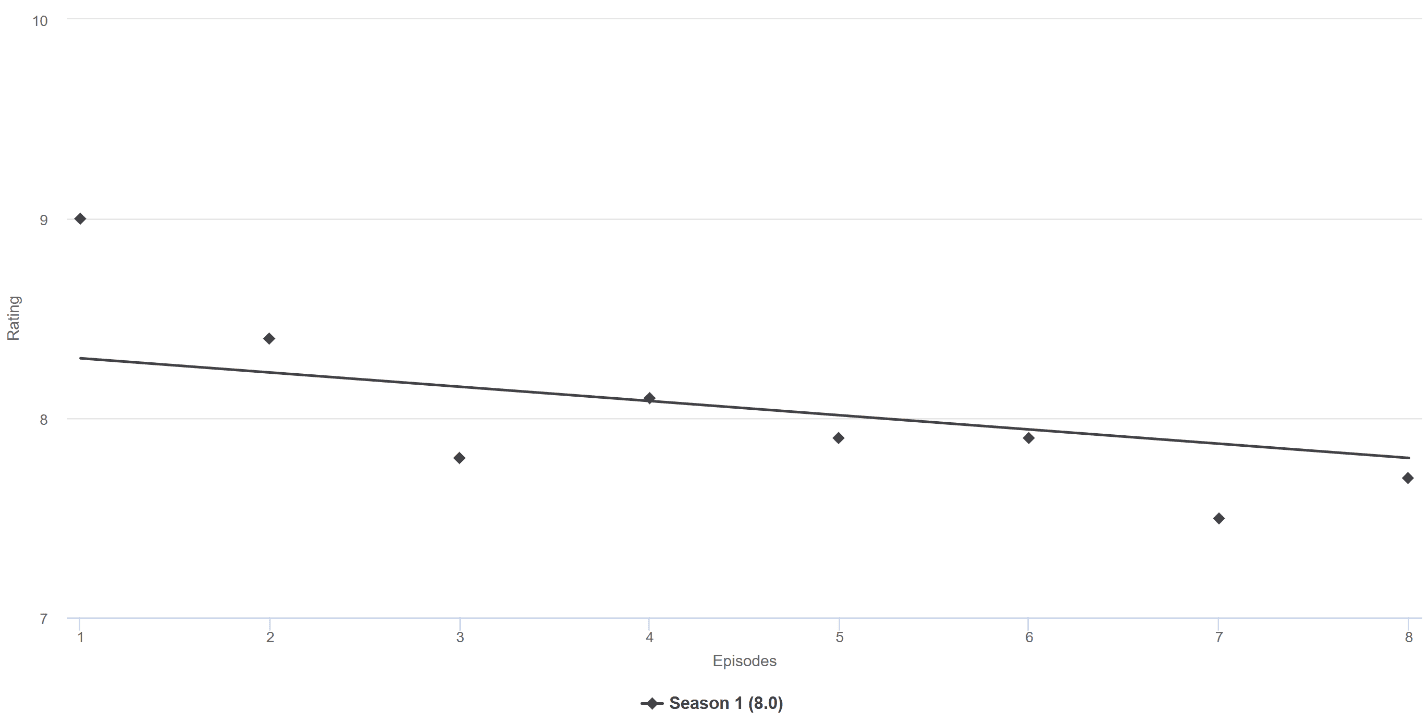

Perhaps that explains why its IMDb user ratings gradually meandered downward before the finale: The show was testing the patience of people conditioned to expect stunning new developments to drop at the speed of, say, Paradise’s. (Although Apple buzzed about Pluribus’s record launch for a drama on the tech titan’s underappreciated streaming service, the show hasn’t been making Nielsen’s weekly top 10 streaming TV series rankings, and it fell off of Luminate’s list after the two-episode premiere.)

But while many mystery-box shows suffer from diminishing returns (or run off the rails entirely when they can’t keep quickly laying track), Pluribus could grow richer and more intense over time, the way both Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul did. Just not because we’ll finally find out some hidden truth about the nature of its world, à la Stranger Things saving some grand reveal about the Upside Down for its series finale. More because Carol might make up (or change) her mind about the best way to live—and our thinking could evolve along with hers.

By the end of the Pluribus premiere, we know what everyone wants: The conflict is created, the ground rules and stakes are set, and the drama is derived from those starting conditions. That’s not to say that there aren’t unanswered questions about Pluribus’s plot. In fact, there are plenty, and “La Chica o El Mundo” drops some fresh hints, as Manousos tries to disrupt the Others’ mesh network and pry possessed people out of the pack. Almost every show, like daily life, contains some amount of mystery. (Even in Abrams’s original formulation, the mystery-box concept was squishy.) But on Pluribus, mystery takes a back seat to diligently, sensitively, and often amusingly gaming out the implications of the series’ profoundly distressing—and intriguing—setup.

Pluribus’s Apple TV teammate, Severance, may be the best of both worlds, which has made it popular with the public and critics alike: It’s a committed mystery-box series that nonetheless seemingly knows where it’s going and offers a steady stream of answers, meaningful character arcs, and deep thoughts. Pluribus hasn’t struck the same balance, and doesn’t seem to be trying to, which probably makes it more of an acquired (or in some cases, discarded) taste. But the makers of Pluribus know what they want it to be, whether or not the show’s prospective audience is seeking the same thing—and the finale reinforced that the series’ stakes come from familiar characters, not from unknowns. To embrace Pluribus, one must make like the last shot and leave the mystery box behind.