Near the end of Noah Baumbach’s Jay Kelly, the eponymous aging A-lister (George Clooney) finds himself alone in the woods on the phone with his eldest daughter. Jay has spent his life chasing professional success and stardom at the expense of building meaningful relationships with his children. Now, on the eve of attending a retrospective of his own career, he’s reckoning with his choices, trying to rationalize and justify his celebrity, his career, his movies, and what it all cost him. “I was young and I wanted something very badly, and I was afraid if I took my eye off of it, I couldn’t have it,” he tells her. “It was supposed to be temporary.”

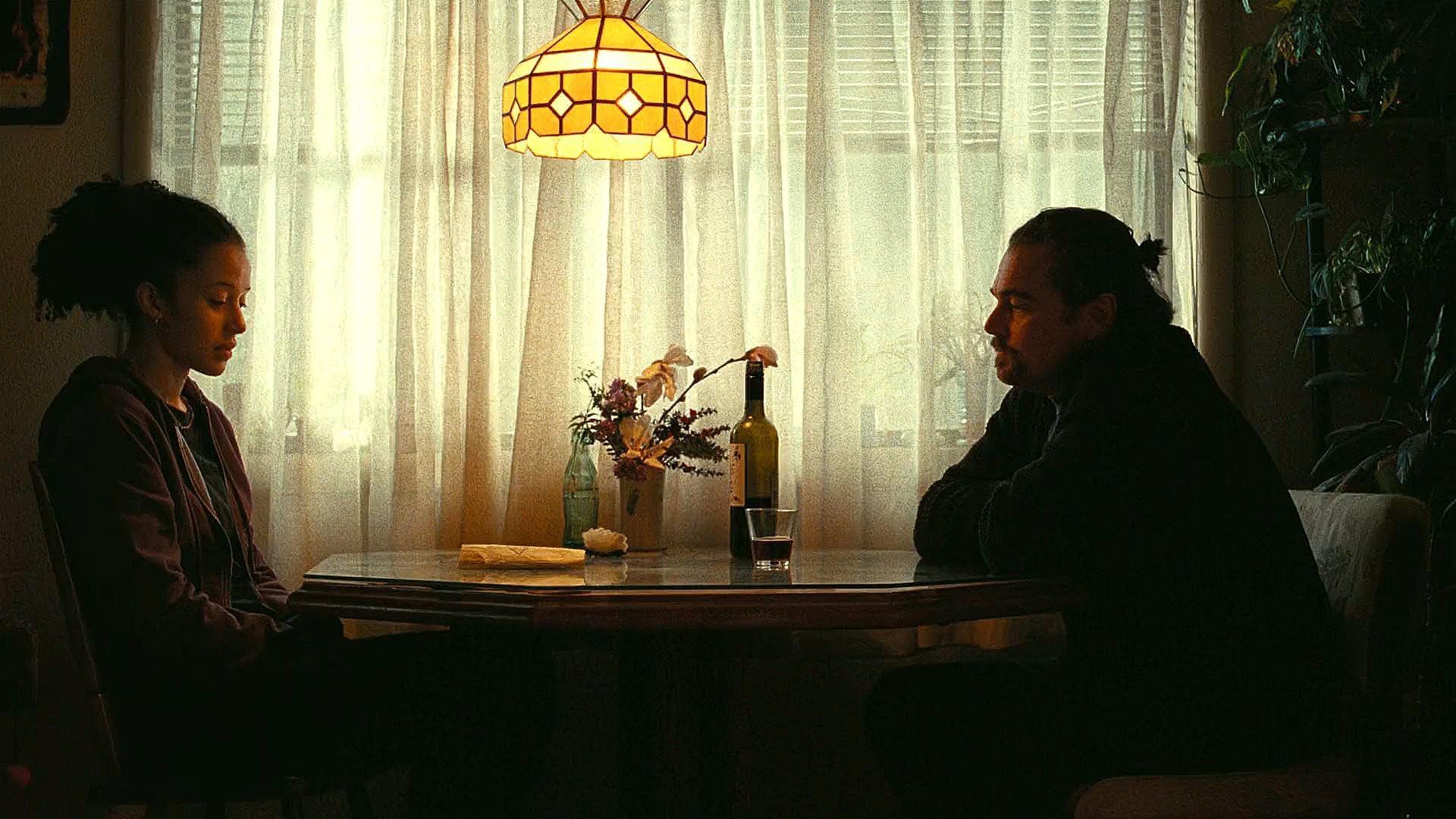

Gustav Borg (Stellan Skarsgard) is struggling with a similar problem in Joachim Trier’s Sentimental Value. The acclaimed Scandinavian filmmaker has returned to his family home to be with his two adult daughters after their mother, his ex-wife, has died. Gustav was absent for the majority of their lives, and his mere presence triggers his eldest, Nora (Renate Reinsve). At this point in his life, his bids for reconnection seem to start and end with his self-absorbed work. “You two are the best thing that’s happened to me,” he tells both daughters at one point. “Then why weren’t you there?” Nora replies.

The weight of paternal absence is even heavier in Chloe Zhao’s Hamnet, a 16th-century romance that turns into a parental tragedy. As his wife, Agnes (Jessie Buckley), raises their three children in Stratford-upon-Avon, a young William Shakespeare (Paul Mescal) struggles to balance his work as a playwright in London with his domestic duties. When his extended trips to the city demand more time, he misses the devastating death of his son to sickness—and remains largely unavailable to his family as they grieve. “You’re caught by that place in your head,” Agnes snarls at him. “You should have been there.”

This year at the movies, dads were in crisis. Nearly every week, another ambitious, flawed, singularly focused striver and provider—haunted by his past and scrambling to outrun the damage he’s done—stumbled onto the big screen, desperate to reconcile before time runs out. The theme stretched across genres and auteurs alike: Paul Thomas Anderson pitted a pair of ideologically opposed, ill-equipped fathers against each other in One Battle After Another. Scott Cooper charted paternal trauma in Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere, capturing the legendary rocker’s fraught, isolated upbringing. And Guillermo del Toro leaned into the inherent father-son friction of Frankenstein, painting his monster’s maker as a monster himself. The pattern continued in Paul Greengrass’s The Lost Bus and Derek Cianfrance’s Roofman, centering fathers trying to atone for the damage done to their own children by stepping in to guide someone else’s. In The Mastermind and The Phoenician Scheme, Kelly Reichardt and Wes Anderson, respectively, framed fathers as flighty dreamers and criminals using or losing their kids to get what they desired. Ronan Day-Lewis turned a father’s isolation and distance into an emotional ice storm in Anemone, while a father-to-be in Josh Safdie’s Marty Supreme chased his dreams with such intensity that he couldn’t understand his true purpose until it was looking him in the face. Even documentaries couldn’t escape: Portraits of Ben Stiller and Martin Scorsese reflected artists still grappling with careers that prevented them from having more present, nurturing home lives.

Programming coincidences are a tale as old as Hollywood. Often, how a given year’s slate of films coalesces can be explained by the cold, hard whims of a handful of studios. But other times, larger societal trends seep into the film stock. Stories of absent and contrite fathers are by no means new, but in 2025, their concentration was less a coincidence than a collective response to a rapidly changing moment.

In his new memoir, Notes on Being a Man, author Scott Galloway lays out what he believes are the three tenets of masculinity: “Men protect, provide, and procreate.” But it’s that second responsibility that most fathers trip on, struggling to negotiate and balance the core tensions of home life and work life. As Galloway notes, a dad’s job is to evaluate and manage the trade-offs of traveling, working, and making money, which often interfere with being present and accessible to their children. “Being a male provider means making hard decisions on behalf of your family,” Galloway writes. “You can have it all, just not all at once.”

That’s a particularly difficult resolution for creative professionals, whose source of work often comes directly from their surroundings—and whose art can often be their only means of communication with the real world. In Hamnet, William’s frequent work trips to London look more like an escape hatch—from parenting, from the pain his own father has inflicted on him—than a paid obligation. After his son dies, William’s grief becomes so unbearable and incommunicable that he can channel it only through his writing, a sublimation that means further abandoning the ones he loves. “When you don’t feel safe growing up as a child, it wasn’t safe around the dinner table, … you escape into the fantasy world. And then that becomes a safe place for you to express the things you couldn't express in real life,” Zhao tells me. “He has no words for it—nor does he feel comfortable crying in front of his family. And the only place he could channel that is his art.”

One of the movie’s most striking images directly interrogates that space, when Agnes and her brother visit William at his London residence to watch his catharsis unfold onstage. Upon arriving, they expect to find him inside a luxurious estate—an oasis from the pain they’ve been inhabiting at home—but quickly discover he’s been toiling and slumming it in a small, one-window room with an unmade bed and messy desk. He hasn’t been ignoring his family’s gaping hole—he’s been coping with it, alone and isolated from the world. It’s in this spare, withered, imbalanced state, in this fantasy box, where he finds purpose and eventually a way to explain his absence.

When you don’t feel safe growing up as a child, it wasn’t safe around the dinner table, … you escape into the fantasy world. And then that becomes a safe place for you to express the things you couldn't express in real life.Chloe Zhao, on ‘Hamnet’

Art as a means of connection also runs deep throughout Sentimental Value. At the movie’s outset, Gustav’s return home—and specifically, his interest in making a film starring Nora, his stage-actor daughter—appears to be a self-centered career move, a way to gather financing by promising another father-daughter collaboration that would echo his earlier, acclaimed work. Understandably, their first interactions don’t go well—she needs a father, not a job. At a pivotal family birthday party for Nora’s nephew, Gustav speaks carelessly about the importance of male artists liberating themselves from their families to chase their artistic needs. “He feels in his own generational liberal punkness that being open is the most virtuous thing, just being straight and talking openly and honestly about the difficult stuff,” Trier says. “He's blind to the fact that she's in need of a much more gentle presence from her father than she's ever been allowed to have, and therefore closes off and becomes counter-aggressive.”

Although Gustav eventually pursues the project with a popular Hollywood actor (Elle Fanning), his intentions—and his film’s significance—come into sharper focus as their rehearsals become increasingly pained. Gustav’s script pulls heavily from recollections of his mother’s suicide, but his words and the story intimately connect with Nora and her own personal traumas, as though he’d been beside her all along. As she reluctantly reads more of his script, Nora begins to reconsider her father’s intentions and comes to understand his previously terse behavior and desire to collaborate as a clumsy attempt at rekindling their relationship.

As Trier has observed, movies have become a “healthy addiction” for creatives in his industry, a world “that they don't know how to get away from,” he says. That’s true for both Gustav and William, which is why both films find their way to the stage in the final moments—a mediated space where each father can finally express what always felt impossible at home. Whether they’re replaying backyard sword fights or resurrecting a private, devastating memory, these recitals of reconciliation don’t provide closure so much as steps toward repair, gestures that signify the artist finally seeing and attempting to heal the wound. “It’s the desire to survive, to give some meaning to all that pain,” Zhao says. “It’s what keeps us going.”

In the title credits of Marty Supreme, Alphaville’s “Forever Young” soundtracks an old-school animation of sperm fertilizing a giant egg. The former belongs to Marty Mauser (Timothée Chalamet), an ambitious table tennis player and aspiring world champion who has just accidentally impregnated his longtime friend (and likely soulmate) Rachel (Odessa A’zion) at the shoe store where he works. It’s 1952, and the 20-something has spent his entire young life trying to make something of himself at underground table tennis clubs, the precise location where the opening credits conclude. It’s there that the fertilized egg morphs into a small, plastic white ball that bounces over the net and off the wannabe champ’s paddle. In Marty’s world, ping-pong is life—literally.

Over the course of the movie, which spans the nine months from his son’s conception to birth, Marty is relentless in his pursuit of a greater purpose, talking and boasting a big game and disregarding anything that may impede that dream—including the mother of his future child. As Marty cowriter Ronald Bronstein notes, when you’re chasing a goal so determinedly, the present isn’t something to focus on, let alone feel responsible for. “You're living in the future because every single opportunity that comes your way in the present is just laced with its ability to compromise your own ability to achieve the goals that you've ordained for yourself,” he says. “You cannot place your feet firmly on the ground and plant roots. You can't really devote yourself to a relationship.”

There’s a similar quixotic dream that Jeffrey Manchester (Channing Tatum) chases in Roofman, the true story of a veteran and father of three so intent on providing for his family that he resorts to robbing dozens of local McDonald’s franchises and loses his kids in the process. In constant pursuit of a suburban American lifestyle and struggling to make ends meet with low-paying jobs, he uses the stolen cash to furnish his three kids with beautiful bikes and big-screen televisions, attempting to become someone he felt they deserved. “He had a job. His wife had a job. Sometimes they had two jobs. And they still couldn't afford the rent. That's why he went to this life of crime,” Cianfrance says. “He wanted to be a part of that middle-class culture somehow, so he started to take from the corporations that were taking [from him].”

He's been allowed to dismount this wild horse. And there's an opportunity for him to root himself.Ronald Bronstein, on ‘Marty Supreme’

After spending four years cut off from his biological children while he’s in prison, Jeffrey gains a second chance at fatherhood when he escapes, bolts to Charlotte, and camps out inside a Toys R Us. Living a spartan existence behind toy stands and using staff facilities to bathe, he begins to crush on Leigh (Kirsten Dunst), a store cashier whose church welcomes him to its worship services. As he develops a covert relationship with her, she invites him into her two daughters’ lives, allowing him to be the kind of dad he always wanted to be. He gifts them loads of stolen toys, reads them bedtime stories, and makes home-cooked dinners, as if making up for lost time. In some ways, he’s the platonic ideal of a present, attentive father—if that father weren’t also a criminal who held up service-industry workers with a firearm.

That theme echoes Kevin McKay’s heroism in The Lost Bus, another true story. It follows a blue-collar bus driver (Matthew McConaughey) who’s unable to communicate with his own son but is thrust into rescuing 22 schoolchildren and driving them through a massive wildfire in Paradise, California. Both know that they can’t make up for their past mistakes, but they can still try to care for the people around them—a redemptive act that, in Jeffrey’s case, expires once the police catch on to his clandestine existence. Cianfrance could feel the sad irony enveloped in his entire story. “It was his bad choices to commit these crimes—his ambition for a house, to be a dad, and to be a provider in the way that he thought—that screwed up the whole situation,” he says. “He made these stupid choices, and then he couldn't provide anything.”

The present also catches up with Marty the instant he locks eyes with his newborn son. It’s a surge of clarity and emotion, but also the start of something, not the end. Like the movie, he finally exhales, taking in the weight of his new role. He can’t be young forever. He just has to grow into the person he’s been constantly running from. “I don't know what kind of father he's going to be. I don't know what that looks like,” Bronstein says. “I just know that right now he's been allowed to dismount this wild horse. And there's an opportunity for him to root himself.”

Chase Infiniti and Leonardo DiCaprio in ‘One Battle After Another’

“All my memories are movies.”

Ronan Day-Lewis can relate to that line in Jay Kelly. The 27-year-old filmmaker and painter spent key stretches of his childhood following his mother, filmmaker Rebecca Miller, and father, the Oscar-winning actor Daniel Day-Lewis, to various film sets, watching the latter transform into iconic characters. “When my parents were making The Ballad of Jack and Rose, it was a really potent experience to see that kind of constructed reality and world get built—and then see them working inside it,” he says. Although his father was around the house much more than other peers, Ronan admits that he always felt an air of mystery around his dad’s process. “He was disappearing into another world when [he went] off to work,” he says.

The feeling stayed with him as the pair began writing Anemone together. Set in northern England, the slow-burning meditation on trauma and isolation hovers around Ray (Day-Lewis), a disgraced former British soldier who’s spent the past 16 years living in shame as a hermit in the woods. His retreat from society—a way of shielding his destructive past from his family—is interrupted when his brother, Jem (Sean Bean), visits unannounced and requests to shack up with him. Ray’s son, Brian (Samuel Bottomley), has begun to spiral down a self-destructive path, behavior that his mother believes only Ray can rectify. To conjure him from the forest and restore the household will require deep, psychological work.

Ronan originally conceived the movie to be about brotherhood, but as he considered his own experiences and collaborated more in depth with his father, he began to think about the impact of Ray’s estrangement and how it might shape a teenage son’s perspective. “Even though there's nothing explicitly autobiographical about that aspect of the film, … there was something I could understand: this sense of deep fascination with the mystery of your father’s past life, or a parent’s past life,” he says. “Ray's legacy is notorious and is something that's been almost a family blight or a family secret. But there were certain aspects we started to realize had some echoes of reality.”

Ray’s internal, stoic response to trauma—reflected prominently in Deliver Me From Nowhere, in which Bruce Springsteen wrestles with his father’s domineering shadow—feels rooted in a generation of men taught to prioritize toughness and project strength at the cost of true connection. “The essence of traditional masculinity is invulnerability, and the problem is that we humans connect through vulnerability,” the therapist Terry Real recently told The New York Times. Encouraging those defenses to crumble then becomes a Herculean task, one that Jem eventually achieves through verbal and physical confrontation, pushing Ray to show up at the home he abandoned. “There's no way to know exactly what's going to happen after he steps into the house,” Day-Lewis says, but it feels like monumental progress.

The inverse response shows up in Happy Gilmore 2, a slapstick comedy that still finds room to sit with grief. After Happy (Adam Sandler) kills his wife with an errant drive, he spirals into an alcoholic depression, quits playing golf, and loses nearly everything outside of his five children. More than a decade later, he’s retired from golf, making ends meet at a grocery store, and working through loss and guilt as a flawed but present father. When he eventually returns to the sport in an effort to put his daughter through ballet school, his family shows up in the same way, championing their father’s comeback and removing alcoholic temptations around the house.

That healthier response to tragedy would seem to be a natural reflection of Sandler’s own relationship and preoccupation with family. Unlike the manager he plays in Jay Kelly, interrupting doubles tennis matches with his daughter and losing valuable time with his son to chase his celebrity client around the globe, Sandler has made it a priority to involve his family in a variety of his productions, conflating work and home life to stay more connected and involved. “I think your first instinct is to write how you relate to your kid or maybe how your dad related to you,” says Happy Gilmore 2 cowriter Tim Herlihy. “The way that Adam talks to his kids in the movie is the way Adam talks to his kids in life.”

Ronan found that working with his own father was a connective, almost out-of-body experience. While shooting Daniel during Ray’s monologue scenes, Ronan remembers looking at the monitor and sometimes forgetting he was watching his father. “I think that there is a catharsis in being able to explore really dark, upsetting themes, but from such a safe vantage point of working on it in this domestic environment, where we know that we have this really strong relationship and we can have a sense of humor about it,” he says. “It felt like it was expressing something deep and something true.”

If there’s a single image tying all these movies together, it’s a weepy father looking at his child with an overwhelming intensity, caught between regret and hope for the future. The list of examples is long: Marty gazes at his son through a window in the neonatal unit; Jay observes his daughters staging a play; William relives his son’s dying breaths; Gustav meets Nora’s eyes with a concerned, knowing smile; Ray studies Brian in disbelief from the sidewalk; Bruce sits in his father’s lap after a show; Bob Ferguson, lying on his couch, cautions his daughter to drive safely; Happy watches his children head through airport security.

Ben Stiller’s family documentary, Stiller & Meara: Nothing Is Lost, is a collaged portrait of his comedic duo parents that began as an act of preservation and turned into a personal reckoning with his own parenting. The doc sprouted after Ben’s father, Jerry, died in 2020, the same year the family’s Upper West Side apartment was due to be sold. But it found greater purpose through the pandemic, when Stiller moved back in with his wife, Christine Taylor, and two children. In that reconnective time, he discovered that he’d been less present with his children than he’d originally thought—a fact he owns up to in the movie. “To actually have, now, a real relationship with them, I feel very fortunate,” he told The New York Times. “It took me a while to really understand the work that you have to put in, to make that happen.”

Polarization, anger, and machismo aren’t the way forward.Joachim Trier, on ‘Sentimental Value’

Of course, not every depiction of fatherhood this year required filmmakers to tap into their own fraught, personal relationships. Trier makes it clear: “I’m trying not to be Gustav Borg.” He adds, “There was a moment when we were in preproduction and my eldest daughter had a kindergarten play and I just said, ‘I got to split, guys.’” But he has felt a changing tide in recent years as the discourse around isolation and disconnectedness has become more prevalent. At a press conference at Cannes earlier this year, the filmmaker announced: “Tenderness is the new punk,” a sentiment even Superman—arguably the most masculine superhero in comics—echoed a couple of months later in James Gunn’s adaptation. “I need to believe that we can see the other, that there is a sense of reconciliation,” Trier added. “Polarization, anger, and machismo aren’t the way forward.”

This gentler redefinition of masculinity (highlighted by increased empathy, heightened awareness of mental health, and more acceptance of diverse identities) might also be a symptom of changing domestic duties and family dynamics. As Galloway points out, women today are the primary breadwinners in 41 percent of U.S. households, and the percentage of women who outearn their husbands has tripled in the past 50 years. That means more husbands are taking on the majority of caregiving responsibilities, reconsidering their value at home, and looking inward. As much as men feel the need to “slay the dragon and have purpose,” as Zhao puts it, these shifts have forced many fathers to consider the relationship with their own vulnerability and inner child. “It is a progression to get to inner work that can lead to wholeness,” she says.

At a time when the highest leaders in government are parading cruelty as a virtue, promoting distorted models of masculinity on social media, and turning atrocities into politicized highlight reels, filmmakers are pushing back and reframing father-child relationship dynamics with more honesty, vulnerability, and accountability. “You think about wars, you think about the environment, you think about AI, and you think about the world that we are leaving our kids and that they're responsible for,” Cianfrance says. “There's a lot of repentance and guilt. Like, we fucked it up—let's try to make it better.”

The impact is already being felt. About a week before Roofman premiered this fall, Cianfrance received a call from Jeffrey Manchester’s biological daughter. She’d been reluctant to speak with the writer-director during the movie’s production, and to his knowledge, she hadn’t spoken to her dad in 15 years. But after watching the movie, she began to have second thoughts. “I've talked to her a few times since the movie has come out,” Cianfrance says. “She's talking to her father again.”