No One Is Having a Worse Time Than Bill Belichick

The greatest coach in football history has become a national punch line. As North Carolina’s season keeps sinking to new depths, the vibes in Chapel Hill aren’t just bad. They’re an all-time disaster.His voice sounds like contempt. This is nothing new, of course, when it comes to Bill Belichick, he of the deadened eyes and the six Super Bowl rings, of the once-spoken and now-eternal wisdom: We’re on to Cincinnati. But still, as he stands inside the lobby of the University of North Carolina’s football facility, mere moments after yet another excruciating Tar Heels loss, with an increasingly antagonistic press corps seated before him and his 24-year-old girlfriend, Jordon Hudson, watching from the corner of the room with a seemingly bemused look on her face, the apparent loathing in Belichick’s voice is a marvel to behold.

On the decision to go for two after scoring in overtime: “Just trying to win the game.”

On the no. 1 option on the game’s final play: “Whoever’s open.”

Bill Belichick during the game between the Tar Heels and the Virginia Cavaliers on October 25

Transcriptions of his words do them no justice. He sounds like he hates everyone who asks him anything. He sounds like he hates everyone who doesn’t. He sounds like he hates you—yes, you—sitting at your desk or scrolling through your phone, simply because now you are reading this very sentence, written by a person who once appeared in his presence.

He sounds this way even when asked the gentlest of questions, like whether the Tar Heels can spin their performance in a 17-16 loss to Virginia forward and carry the positives into Friday’s matchup against Syracuse. He’s asked this by a chipper young man whose energy suggests a belief in the Heels: how hard they fought, how fervently they are improving, and how lucky they are to be learning football from the man who knows the game better than anyone else who has ever walked this earth.

Belichick’s response: “I don’t know what’s going to happen.”

No one does. All we know is this: Last December, North Carolina hired a 72-year-old man, widely regarded as the greatest coach in football history, to lift the Tar Heels program to new heights. Eleven months later, the team is 2-5 overall and 0-5 against power-conference opponents, representing Carolina’s worst start since 2017. The Heels have attracted far more attention for their coach’s love life and reports of their off-field dysfunction than for anything they’ve done on Saturdays. All of this on the watch of a man whose greatness has long been beyond question, who built and then rebuilt a decades-spanning dynasty in New England, who sits alongside John Wooden, Phil Jackson, and Nick Saban as one of the most towering coaching figures in American sports history. A man who now stands at the podium and stares glumly off into the distance, mumbling disaffected nothings until it’s time for him to leave.

Says Belichick: “It’s not good.”

It must be said: There are few places on the planet more pleasant to watch a terrible football game than Chapel Hill in late October. The sun is soft and bright; the blue in the end zones gives way to the blue in the empty seats that gives way to the slightly deeper blue in the sky. Footsteps from the stadium, Collective Soul is playing a concert on the quad, and even 30 years after its release, “Shine” still goes hard. All along the pathway from the quad to the stadium gates, tailgaters drink coffee, mimosas, and morning beers. They’re in a state that features the majesty of the Smokies, the serenity of the Outer Banks, and the charm of Asheville, but on this Saturday they’ve chosen to be here, watching a septuagenarian lead a moribund football team to yet another defeat.

They didn’t expect it to be this way. “I drank all of the Kool-Aid,” says Daniel Daum, a California native who moved to the Triangle, fell in love with the Heels, and has now had season tickets for about 15 years. “I had, like, three jugs of Kool-Aid.” After the school announced that it had hired Belichick, Daum settled on a firm belief: “We’re gonna go undefeated.” He called the athletics department and asked to upgrade his seats. He wanted to watch the Heels ascend to national title contention from the very best view he could afford. His thinking was simple: “This guy’s the greatest coach in the history of the sport. He’s going to have money to bring in a good staff. And talent is going to flock.”

For at least a little while, Carolina fans could believe in this version of the future. On the evening of Monday, September 1, the eyes of the football world were on Chapel Hill. TCU came to town. So did ESPN’s College GameDay. Distinguished UNC luminaries Michael Jordan, Lawrence Taylor, and Roy Williams all watched from a luxury box. Randy Moss sat just a few seats away, chatting with Hudson in the buildup to the game. “I had never seen the stadium that full,” says Daum. “Ever.”

Fans painted to spell “Chapel Bill!” cheer before the game between North Carolina and TCU on September 1

For so long, North Carolina has been billed as one of college football’s sleeping giants: a school with money, passion, and proximity to elite recruiting talent. If nearby schools like Clemson and Tennessee could reach the highest levels of the sport, why couldn’t they? Mack Brown got them close in the late 1990s, but then he left for Texas. Larry Fedora took them to the brink of an ACC championship in 2015, but then they lost to Clemson in the conference title game and haven’t cracked double-digit wins in a season since. But now: this. Belichick. Sure, some national analysts had predicted a disaster—“Congratulations, North Carolina. You managed to hire someone completely unqualified to be your next football coach,” wrote Stewart Mandel of The Athletic—but the case for him to succeed was clear.

And on the very first drive of Belichick’s very first game, everything clicked into place. UNC marched down the field, 83 yards on seven plays, blowing TCU off the line of scrimmage as the run and pass games operated in perfect rhythm. As running back Caleb Hood plowed into the end zone, the building reached a volume typically reserved for late February in the Dean E. Smith Center. Carolina-blue fireworks detonated in the late summer sky. “Holy shit,” Daum remembers thinking. “I can’t believe this is real.”

And, well, it wasn’t. The Horned Frogs answered quickly, scoring 41 consecutive points and winning 48-14. The Tar Heels lost their first three games against power-conference opponents by a combined score of 120-33. The greatest coach of all time had arrived in Chapel Hill and promptly led the Heels to the worst start in the history of the program—dating all the way back to 1888. “It was bleak,” says Daum. “B-L-E-A-K bleak. You’re just looking around like, ‘This is a disaster.’”

And that’s just on the field. Off it, the Heels keep drawing the exact wrong kind of attention. “It would be kind of nice to feel like we’re just covering a football team,” one of the local reporters tells me in the press box. “But the biggest stories are everything else.”

Local television station WRAL has thrown an army of reporters at chronicling the Heels’ dysfunction. In college town media markets, where there’s usually no other game in town, reporters are often friendlier to coaches than in major markets like, say, New England. That’s not the case in Raleigh-Durham. It’s a market with three prominent college programs, all basketball powers, and NHL and NFL teams, the Hurricanes and the Panthers, who play just down the road in Charlotte. Local media has no real incentive to cozy up to the nearby football coach, and their reporting shows it. “It’s an unstructured mess,” WRAL quoted a source as saying about Belichick’s program. “There’s no culture, no organization. It’s a complete disaster.”

It’s reportedly been this way from the start. Back in March, ESPN reported on the chaotic process that led to Belichick’s hiring—one that began with Belichick telling U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio, of all people, that he wanted the job. Rubio then informed North Carolina Senator Thom Tillis, according to ESPN, who passed word along to UNC officials. Internally, they were divided. Athletics director Bubba Cunningham had put together a long list of candidates, including several of the hottest names in coaching, such as Tulane’s Jon Sumrall and Iowa State’s Matt Campbell. But the university’s board became fixated on bringing Belichick to Chapel Hill.

The board got its man, and Belichick arrived with broad authority to run the program exactly as he saw fit—a level of autonomy that would not have been offered in any of the NFL jobs that he was linked to after parting with the Patriots. He brought in his son Steve Belichick as defensive coordinator; his girlfriend, Hudson, to manage his personal business; and his longtime colleague and confidant Mike Lombardi (a former Ringer podcaster) as general manager. They talked like a group that felt confident they could quickly transform Carolina into a contender. “We consider ourselves the 33rd [NFL] team,” Lombardi said in March.

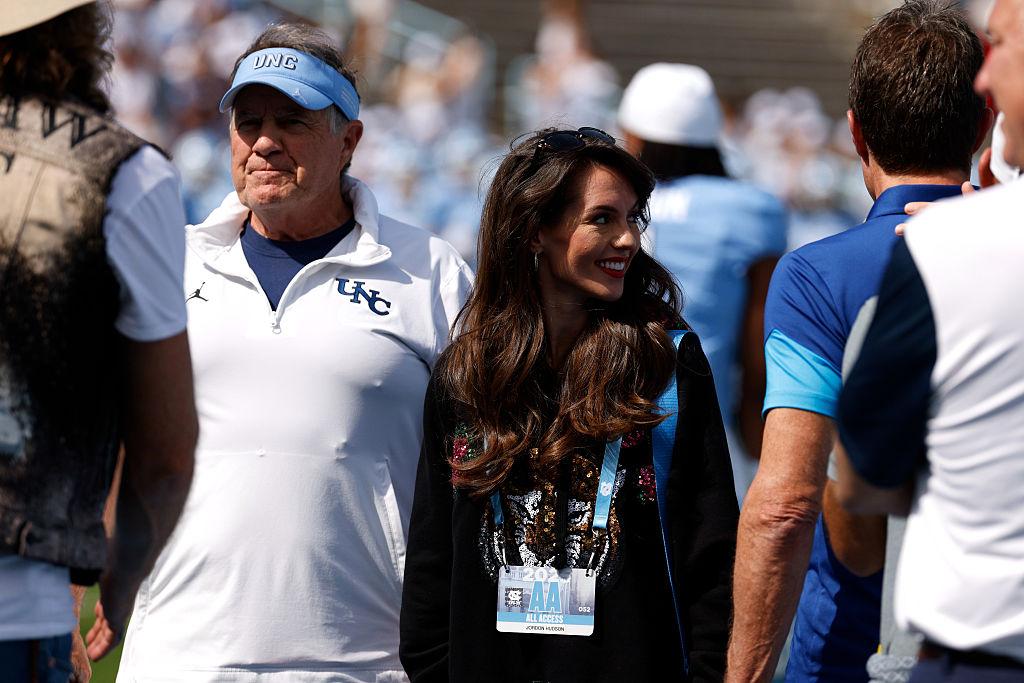

Belichick and Hudson before the game against the Richmond Spiders on September 13

The spring and summer were dominated by a disastrous book tour promoting Belichick’s The Art of Winning, which hit its peak of dysfunction when Hudson hijacked a CBS interview, declaring that Belichick would not answer questions about how the two of them had met. Investigative reporter and podcaster Pablo Torre dug into Hudson’s role in Belichick’s personal and professional affairs, painting a picture of someone who is intimately involved in many major decisions Belichick makes about how to run the Tar Heels program. More recently, Torre dug into Lombardi’s past and also reported that Lombardi had spent time this preseason in Saudi Arabia trying to raise money from a repressive and violent petrol state so that he could help to afford the kinds of football players the Tar Heels need to win games.

It’s, well, a lot. And that’s before even mentioning the suspension of cornerbacks coach Armond Hawkins for recruiting violations—a truly impressive feat, in the age of NIL—or WRAL’s reports of transfers getting preferential treatment over holdovers from the staff of Mack Brown, who returned to UNC as coach in 2019 after Fedora was fired. Or, perhaps most notable: A report that Belichick was already considering leaving Chapel Hill less than a year into his tenure, which he has called “categorically false.”

“Everyone’s saying Belichick was leaving,” wide receiver Jordan Shipp says after the Virginia game, referring to the online chatter. “I heard he was leaving even before the season started. … So we’re tired of hearing that.”

Yet, somehow, you can find flickers of hope in Chapel Hill. After getting destroyed by TCU, UCF, and Clemson, North Carolina nearly beat Cal in Berkeley, losing only after receiver Nathan Leacock fumbled at the goal line instead of scoring what could have been the game-winning touchdown. And against 16th-ranked Virginia, Carolina limited one of the hottest offenses in the country to only 10 points in regulation, losing when it came inches short of converting an overtime two-point conversion that would have won the game. “We’re getting better,” Shipp says at the podium minutes after the Virginia game, jersey and pads still on. Adds defensive end Melkart Abou Jaoude: “You guys saw it today. We felt it today. Just a few mistakes here and there that we’ve gotta clean up, and the outcome would have been different.”

Fan attendance for the Virginia game was scattered and late arriving, but those who showed up still clung to belief. Daum, the fan who was convinced that the Heels would go undefeated after hiring Belichick, still thinks that the best is yet to come. He copes by telling himself that Carolina missed its window last offseason, that Belichick wasn’t hired in time to lure the best transfers. (Notably at quarterback. The Heels had reportedly targeted Quinn Ewers and John Mateer before bringing in South Alabama transfer Gio Lopez, who has struggled to adapt to power-conference football.) Another fan, Landry Moore, shares that optimism but gets more philosophical: “It doesn’t really matter who the coach is. I’ll always believe in the Heels.”

Tar Heels players take the field before the game against the California Golden Bears on October 17

The players insist on their own togetherness, their desire to bring the best out of one another and turn this season around. But the losing wears on them. “Man,” says Shipp, “it is hard. I was just sitting there, just shedding tears with some of the boys in there. It means so much because of how much we really pour into it. You pour so much into it, and you lose a game two weeks in a row by a couple inches.”

The final days of great careers are often ugly. Michael Jordan carrying a paunch in a Wizards jersey. Shaquille O’Neal averaging fewer than 10 points per game in Celtics green. Bear Bryant watching his Alabama dynasty drift toward mediocrity. The maniacal intensity that pushes an elite few to the top can keep them hanging on too far past their peak.

And so Belichick is here, standing at a podium in North Carolina, mumbling disdainfully at the assembled press horde after his nightmare season has just gotten worse. Nothing he says or does can erase all that he accomplished in New England. But here is a new memory, more fleeting but no less real, of this giant of the sport reduced to explaining the latest in a string of embarrassments and failures. “Everybody’s improving,” he says, and maybe this is some solace as his miserable first and potentially last season in college football winds toward its end.

He steps away, walks toward the glass doors, and vanishes into a hallway. He’s on to Syracuse, at least for now.