Things went south for Seattle in Game 7 of the ALCS as soon as the first Mariners reliever entered the game. When Bryan Woo—a starter working in relief of actual starter George Kirby—gave way to Eduard Bazardo in the bottom of the seventh, with one out and runners on second and third, the Mariners were leading 3-1. Two pitches later, they were trailing 4-3, after the Blue Jays’ George Springer produced the most consequential play in ALCS history, by championship win probability added: a three-run, game-winning homer.

Perhaps Seattle’s mistake wasn’t bringing in a reliever, but bringing in that reliever. Or maybe the bigger issue was the presence of Springer, whose homer not only propelled Toronto to a pennant but also sent Springer to the top spot on the all-time postseason cWPA leaderboard. Nevertheless, when the Mariners went away from their regular-season starters, the situation got worse for them and better for the Blue Jays, who got two scoreless innings in Game 7 from starters moonlighting in relief: Kevin Gausman (who was credited with the win) and Chris Bassitt (who held Toronto’s tenuous lead in the eighth).

There’s nothing normal about a Game 7 or even an earlier potential pennant clincher. (In Game 4 of the NLCS, five of nine relief innings were thrown by two starters—the Brewers’ Chad Patrick and the Dodgers’ Roki Sasaki—who combined to allow a lone run.) But the sight of starters making midgame entrances has seemed normal this month. So far this postseason, 29 pitchers who made more than half of their regular-season appearances as starters—including 22 who made at least 80 percent of their regular-season appearances as starters—have pitched in relief. On the whole, they’ve fared so well that comparatively speaking, nonstarters have been, well, nonstarters.

Postseason Relief Performance by Regular Season-Role

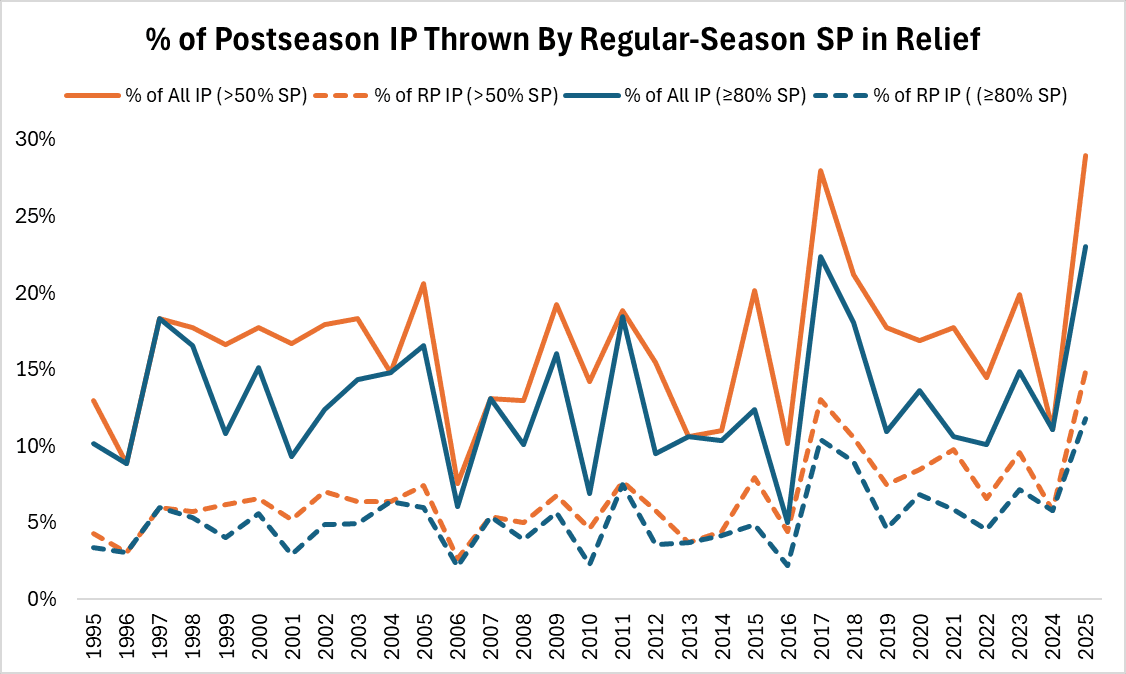

The degree of relief reliance on starters we’ve seen in these playoffs is unprecedented in the wild-card era. In 2025, playoff relievers who made more than half of their regular-season appearances as starters have accounted for 14.9 percent of all postseason innings and 29 percent of all postseason relief innings. For playoff relief pitchers who made at least 80 percent of their regular-season appearances as starters, those rates stand at 11.8 percent and 23 percent, respectively. All of those figures would be new highs in the wild-card era, which now spans 30 years.

Generally speaking, there are five ways in which starters get deployed out of the pen in the playoffs. In ascending order of real relieverhood (from “still a starter, masquerading as a reliever for a limited time only” to “permanent occupant of the postseason pen”), they are:

- As “break glass in case of emergency” options: When games go long, pitchers must, too. Eventually, teams’ stockpiles of regular relievers dwindle, and managers have little choice but to call on whichever starters have the most relief experience or will most minimize disruption to the rotation if used in an unscheduled outing. The blissfully zombie-runner-free, 15-inning winner-take-all tangle between the Tigers and Mariners in ALDS Game 5 featured four regular-season starters who were pressed into service midgame. Keider Montero (admittedly more of a swingman) and Jack Flaherty threw four extra innings for Detroit; Logan Gilbert and Luis Castillo threw 3 1/3 for Seattle. Castillo, who hadn’t pitched in relief since a 2016 stint with the High-A Jupiter Hammerheads, became the winning pitcher after the Tigers fatefully tapped a “real” reliever, Tommy Kahnle, to pitch the 15th.

- As bullpen depth on throw days: Starters typically throw on a set day between starts. So instead of “wasting” those pitches (for short-term, competitive purposes) by throwing a bullpen session before the game, they sometimes simply throw out of the bullpen in the game, thereby getting their work in while also making their managers’ paths to 24 or 27 outs easier.

- As low-leverage alternatives to top late-inning arms, whose contributions can help prevent those regular relievers from getting fatigued or overexposed. (See Clayton Kershaw’s use as a sacrificial lamb in NLDS Game 3—which Dave Roberts would surely like to make the second-to-last outing of Kershaw’s career, if the Dodgers ever have a large enough lead or deficit against Toronto for Roberts to give the ball back to the retiring future Hall of Famer.)

- As “bulk guys”: Of 80 postseason starts, eight have been by openers (three by Aaron Ashby, and one apiece by Andrew Kittredge, Trevor Megill, Troy Melton, Drew Pomeranz, and Louis Varland). Naturally, classifying relievers as starters (and vice versa) somewhat skews cross-era comparisons, but openers and bullpen games have been postseason staples since the late 2010s, so this pattern is nothing new for the era. Brewers phenom Jacob Misiorowski (who leads all regular-season starters with 12 postseason innings pitched) thrived in this role behind Ashby and Megill, so while he was purely a playoff reliever, his workload was more starter-like.

- As dedicated, converted relievers: This is the Sasaki scenario. The Dodgers aren’t deploying their latest high-profile free-agent signee from Japan in the pen between starts; following a late-season conversion orchestrated in Triple-A and then the majors, they’ve assigned him to relief for the duration of their run (and possibly beyond, based on how he’s pitched). Sasaki’s command can be shaky, but he’s mostly looked the part of a wipeout closer in his ultra-high-leverage role.

Some portion of this postseason’s especially starter-centric bullpen approach is happenstance, stemming from the makeup of the playoff field and the unavailability and/or ineffectiveness of certain arms. But for a few reasons, sprinkling starters into a playoff pen can be a sound strategy. It helps ward off the reliever familiarity effect that can arise through repeated matchups between the same pitcher and hitter, a stated goal of Jays skipper John Schneider. It compensates for the fact that relievers aren’t conditioned to pitch as often (or for as long) as they once were, which increases the risk of pushing them past their limits. Plus, pitchers who become starters tend to be more talented than pitchers who become relievers; if spare starters can be turned into viable bullpen arms, they can be powerful playoff allies, particularly if their stuff plays up in short bursts.

Case in point: Sasaki, whose career reinvention has afforded the Dodgers a solution to their biggest obstacle entering October. Contending teams fielded unusually lackluster relief corps this year (which led to a lot of reliever trades at the deadline), and however one slices the splits, bullpen performance wasn’t the strong suit of either the Blue Jays or the Dodgers during the regular season. Toronto’s and L.A.'s reliever FIPs ranked 13th and 17th, respectively, overall; 15th and 16th after the trade deadline; 15th and 20th in the seventh inning or later; 16th and 25th in high-leverage spots in the seventh inning or later; and 20th and 27th in post-deadline high-leverage spots in the seventh or later.

Thus far, the Dodgers have rendered that glaring weakness a nonfactor by employing two neat tricks. First, they’ve used regular-season starters (Sasaki, Emmet Sheehan, Kershaw, and Tyler Glasnow) for 15 of their 27 2/3 relief innings, led by Sasaki, who’s nearly doubled the innings total of any other L.A. reliever. Only one other playoff team from the wild-card era with more than five games played has ever entrusted more than half of its relief innings to regular-season starters—and it’s the one the Dodgers just beat.

The Most Starter-Centric Playoff Bullpens Since 1995

Some recent champions—including the 2017 Astros, 2018 Red Sox, 2019 Nationals, and 2023 Rangers—have famously used starters to paper over holes in the pen, but none of them came close to doing it like these Dodgers. As anticipated, that’s a stark reversal from the Dodgers’ pitching approach last October, when they hardly had enough healthy starting pitchers to do the starting, let alone the relieving, too. Last year’s Dodgers received only 9.8 percent of their playoff relief innings from regular-season starters, less than one-fifth the rate of this year’s club.

That turnabout ties into this team’s other neat trick: sporting such a dominant rotation that relievers are hardly required. Entering the World Series, the 2025 Dodgers’ rotation boasts the best FIP ever (2.00) among teams that have played more than seven postseason games and the best ERA ever (1.40) among teams that have played more than 10.

With the exception of NLCS Game 2, when Yoshinobu Yamamoto went the distance, even the Dodgers have needed some relief. But the Brewers barely budged them off their ideal script of passing the baton from the starter to Sasaki and calling it a day. Roberts deserves some credit for flipping the script after winning the World Series last year with a drastically different pitching approach. Then again, most major league managers could probably decipher how to handle a set-it-and-forget-it rotation composed of four guys as good as Snell, Yamamoto, Glasnow, and Shohei Ohtani. No team since the 2012 Tigers has played 10 or more playoff games with as high a percentage of its innings thrown by starters as these Dodgers’ 70 percent (so far).

Schneider, armed with a much more modest group, hasn’t had that luxury. (Sheehan, who can’t crack the Dodgers rotation, had a better ERA, 3.17, and FIP, 2.93, as a regular-season starter than Kevin Gausman, Shane Bieber, or Max Scherzer did.) The Jays have played 11 postseason games to the Dodgers’ 10, but even so, L.A.’s starters have totaled 13 more innings than Toronto’s. And because they don’t have a surplus of strong starters, they don’t have any candidates to make a Sasaki-esque conversion. (If only they’d succeeded in signing Sasaki in January—though without the 1.8 fWAR they got from Myles Straw, whom they acquired as part of their attempt to lure Sasaki to Toronto, they might have finished second in the AL East, lost the first-round bye, and been eliminated in the wild-card series.)

The Jays have gotten only 6 2/3 relief innings in total from regular-season starters: an inning from Gausman in Game 7, 2 2/3 from Bassitt, and three from Eric Lauer, the last of whom (along with Brendon Little, Mason Fluharty, and Justin Bruihl) numbers among the few, unenticing southpaws Shneider can summon against the Dodgers’ lefty sluggers. Not only can Toronto not match L.A.’s starter-bolstered bullpen, but it may be ill-equipped to force the Dodgers to dip into theirs.

Blue Jays batters saw the fourth-fewest pitches per plate appearance of any team during the regular season (3.78), and they’ve been even more aggressive in October (3.56, by far the fewest among playoff teams). Swinging early helps them stay out of two-strike counts and, by extension, avoid strikeouts (which the Dodgers staff usually excels at inducing). But depending on whether those swings are paying dividends, Toronto’s approach may aid the Dodgers’ efforts to stick with their starters—even the newly efficient Blake Snell—as long as possible.

This is not an October of teams like Kansas City in 2014 or Cleveland in 2016—clubs that aimed to turn over the game to a combo platter of intimidating bullpen monsters and that leveled up when they had a late lead. In a way, what we’ve seen this postseason—primarily, but not exclusively, from the Dodgers, Brewers, and Cubs—is a throwback to an earlier period of playoff pitching. In all postseasons before the wild-card era combined, pitchers who’d made more than half of their regular-season appearances as starters amassed 30.4 percent of playoff relief innings, a near match for this year’s figure—and almost twice the going rate in the wild-card era before 2025.

Go far enough back, and teams barely had bullpens: Before 1969, when the postseason consisted solely of the World Series, regular-season starters threw 45.9 percent of Fall Classic relief innings. These days, there’s no short-relief shortage. But as this month has reminded us, starters are sometimes still a team’s best option even if they didn’t throw the first pitch. Yamamoto was the first postseason starter since 2017 to finish what he started. But for the Dodgers to repeat, they’ll have to keep asking another starter—Sasaki—to finish what one of his former rotation mates started.