Kathryn Bigelow’s A House of Dynamite is a ticking-clock thriller with a structural twist: It’s a nightmare on repeat. After walking us briskly through a doomsday scenario in which the highest echelons of the American government and military complex are informed, out of the blue and to their profound and collective bafflement, that an ICBM of unknown origin has been launched at Chicago with less than 20 minutes until impact, the film rewinds and replays the incident from slightly different perspectives. We get three versions of Defcon 1 in all, each set in a different location and focused on different sets of characters. With each iteration, figures previously glimpsed only in passing or via video screens become fleshed out as protagonists. Not that the broadening of the ensemble makes a difference in terms of the missile’s—or the story’s—trajectory. No matter who’s watching the monitors, the data indicates that there’s nowhere for things to go but down.

A House of Dynamite is written by Noah Oppenheim, the former president of NBC News who’s a controversial figure in his own right. His previous script for Pablo Larrain’s wretched Jackie was similarly preoccupied with elaborate framing devices, perhaps because they let him show off his cleverness as opposed to the workmanlike concerns of linear drama. Beyond its obvious and off-putting self-consciousness, there’s something effective about Oppenheim’s setup for A House of Dynamite: The repetition of certain key lines not only helps orient us within the recursive chronology but also gives the words themselves a preprogrammed, mantra-like quality, which is fitting for a film filled with codes and passwords. The koan that sticks out most is an observation by one high-ranking general—a laconic warmonger played by master actor and reigning king of physical media Tracy Letts—that history is warping in real time. “This is not insanity,” he snarls. “It’s reality.”

Reality—or at least scrupulously researched, authentically textured, quasi-docudrama naturalism—has been Bigelow’s thing since 2009, when The Hurt Locker earned her an Academy Award for Best Director. Bigelow was rightly hailed for breaking the Academy’s glass ceiling even as the film itself arguably fell short of her best work. In Bigelow’s great early films—a sterling decade-and-a-half run from 1981’s The Loveless to 1995’s Strange Days, peaking in between with Point Break (1991)—the former student of critical theory cultivated a genuinely breathtaking aesthetic sensibility, fusing muscular genre mechanics and feminist perspective with a glorious, unorthodox gift for visual abstraction. In Point Break, Bigelow’s wide-screen thirst-trap compositions eroticized Keanu Reeves and Patrick Swayze while conveying their mutual desire—threaded expertly through Bigelow’s own obsessions—for spiritual transcendence; the wild poetic excesses that imperiled its reputation as a “good” movie are why it endures as a great one. But while it was possible to reconcile The Hurt Locker’s story of embedded American bomb-disposal experts in Iraq with Bigelow’s other, glossier exercises in adrenaline-junkie chic, its tone was somber rather than ecstatic, befitting the ripped-from-the-headlines subject matter that signaled Bigelow’s ostensible maturation into a serious and award-worthy auteur.

There is, predictably, far more of The Hurt Locker and its successors, Zero Dark Thirty and Detroit, in A House of Dynamite than Point Break. Still, it’s telling that the one passage that evokes the latter doubles as the movie’s best sequence. After the conclusion of the first installment, which cuts away from a Washington-based control room just as the nuke is about to land, we get a strange, unsettling interstitial featuring a handsome young man bobbing shirtless somewhere in the South Pacific. Rising out of the surf against a gorgeous horizon line, he could be one of Bodhi’s sunbaked Ex-Presidents. He is, instead, a bomber pilot tasked with delivering the U.S.’s retaliatory payload, provided the president—heard but not seen in the first two sections via a blacked-out Zoom camera and finally embodied in the homestretch by Idris Elba—decides to run with the proverbial nuclear football.

We see this lean, anodyne flyboy only a few more times in A House of Dynamite, but there’s something genuinely beguiling—and frightening—in how Bigelow frames him as a clean-cut destroyer of worlds. He’s young, dumb, and full of compliance for a chain of command that's only as strong as its weakest links.

The strongest element of A House of Dynamite is the restless, relentless institutional hum built up by Bigelow and her ace editor Kirk Baxter as they crosscut between tactical and ideological positions. It takes a lot of skill to create a believable workplace environment and to parcel out exposition about entrenched protocol so that it feels natural. The sheer density of information being spoken aloud or scrolled across monitors and iPhone screens here represents some kind of achievement. Unfortunately, it’s in the service of a familiar and facile thesis: that the emissaries of America’s military-industrial complex are ultimately just regular people like you and me, and that, when staring down the barrel of an unimaginable crisis, they’ll do their level best to serve the greater good. This egalitarian idea worked in Sidney Lumet’s 1964 drama Fail-Safe, from which A House of Dynamite borrows both its basic setup and certain key plot points, because the material was presented as a square-jawed moral fable—one with the guts to humanize the Soviets on the other end of the hotline. The near-simultaneous release of Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, with its fun-house-mirror reflections of Cold Warriors fulminating about bodily fluids, rendered Fail Safe’s grim vision of mutually assured destruction unhip. But it still endures as a white-knuckle classic, with Henry Fonda as a symbolic doppelgänger for JFK.

Oppenheim’s vision of grace under pressure plays very differently: as an inventory of received Sorkinisms shoplifted from The West Wing. Given the state of affairs beyond the frame, it’s hard to take this kind of virtue signaling seriously. It turns out that trying to remake Fail-Safe in a Dr. Strangelove world yields more cognitive dissonance than suspense. Watching Elba’s commander in chief agonize over a choice that, as one levelheaded subordinate puts it, basically leverages survival against suicide is harrowing, but it’s also weirdly comforting, insofar as the character seems to have been beamed in from a dimension where Donald Trump doesn’t exist. Despite their varying opinions about the best course of action and the efficacy of de-escalation, the characters here are (almost) all articulate and competent and are given little slivers of backstory that humanize them and bind them to us. In One Battle After Another, Sean Penn reached back to the Strangelove style of caricature, styling Steven J. Lockjaw as a spiritual descendant of Sterling Hayden’s Jack D. Ripper, complete with convulsive paranoia about his enemies being semen demons. What does it say that Paul Thomas Anderson’s stylized phantasmagoria feels more like a movie of the moment than Bigelow’s meticulous, accomplished procedural?

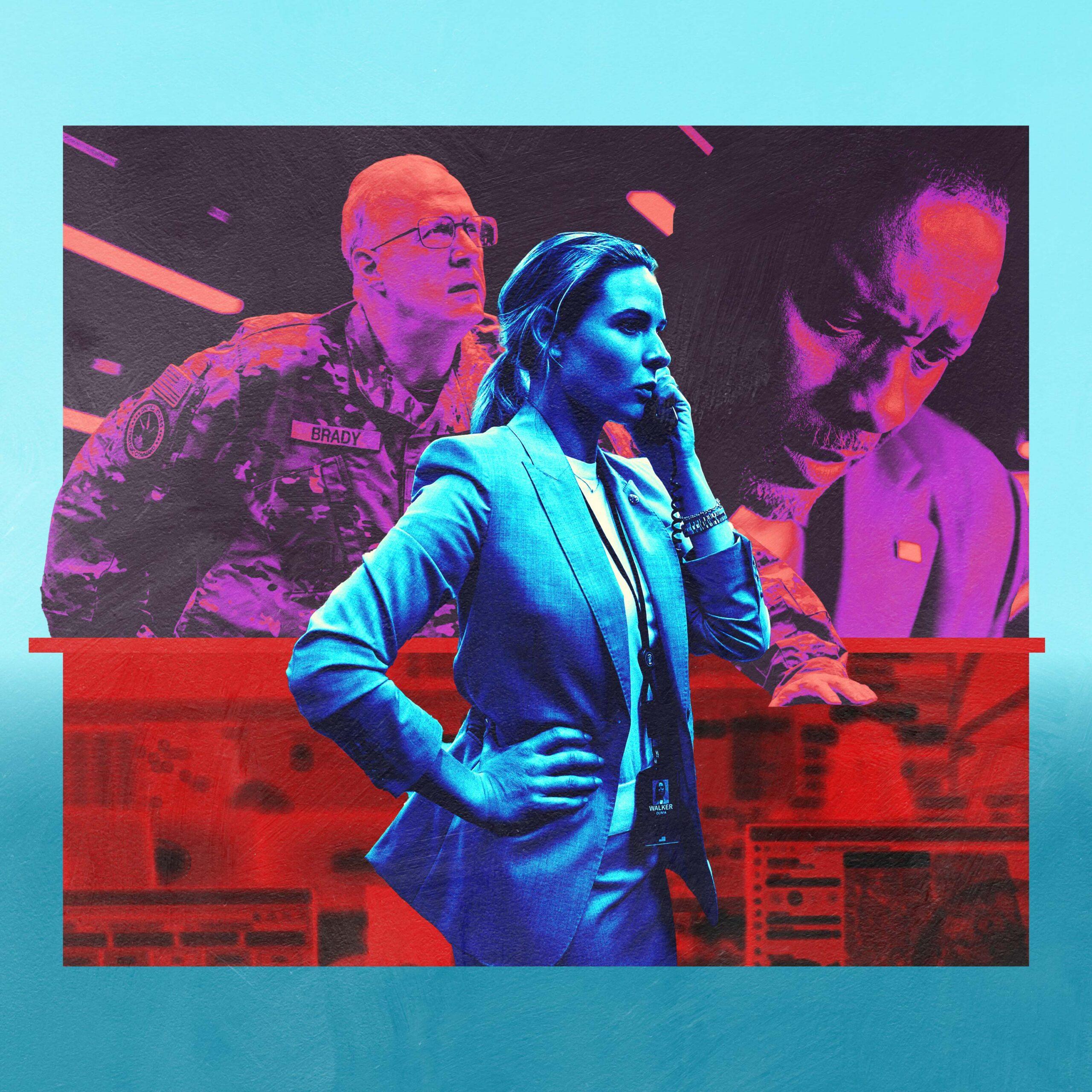

When Zero Dark Thirty came out in 2012, it was pilloried online by progressive commentators who saw its depictions of U.S. military torture as being tantamount to endorsement and its re-creation of Operation Neptune Spear as a form of warnographic spectacle. These charges are worth parsing—I think that the movie is misunderstood—but either way, its most resonant (and troubling) image was Jessica Chastain’s face in the final scene as her character stood in a massive bomber bay, tearstained but resolute, an avatar for American power in the aftermath of 9/11, locked and loaded and looking for someplace to go. Chastain also scanned as a stand-in of sorts for her director—a distaff badass trying to reconcile her personal feelings about a complex situation with her obvious talent for project management. There is a similarly Bigelow-ish figure in A House of Dynamite in the form of Captain Walker (Rebecca Ferguson), the competent but empathetic senior duty officer who anchors the opening segment. When she’s pushed to the sideline by the movie’s structure, the material begins to feel depressurized—which is not what you want given the apocalyptic stakes.

Part of the problem is that the essentially static nature of the situation precludes Bigelow from doing the thing she does best—kinetic, large-scale action sequences defined by weightless, roller-coaster movement. The handheld zooms and portentous musical score reek of prestige television. The other big issue is that Bigelow has stowed the satirical sense of humor—not ha-ha funny, but austerely droll—that powered A-plus B movies like Near Dark and Blue Steel, which felt, for all their tropes and clichés, like the work of an artist. With the exception of the aforementioned pilot bobbing in the ocean, the poetic touches in A House of Dynamite are po-faced and labored: Ferguson clutches a plastic dinosaur bestowed by her son (a symbol of incipient extinction), and Greta Lee’s foreign-affairs expert is stranded at a reenactment of the Battle of Gettysburg so that she has to struggle to be heard on the all-hands Zoom call over the sounds of Civil War–era muskets.

There’s a case to be made that such observations amount to little more than nit-picking in the shadow of Bigelow’s larger aim to provide a global wake-up call about nuclear proliferation, à la 1983’s The Day After, which was watched by 100 million people in prime time and even broadcast on Soviet state television. In interviews, Bigelow, who was born in 1951, has spoken about growing up as a child of “duck and cover” drills; her desire to examine that anxiety through a contemporary lens seems to come from an honest place. “I feel like nuclear weapons, the prospect of their use, has become normalized,” she told Deadline recently. “We don’t think about it, we don’t talk about it. And it’s an unthinkable situation. So, my hope was to maybe move it to the forefront of our lives.”

Of course, just because the scope of the horrors in A House of Dynamite are beyond comprehension does not mean that the film is beyond criticism. In attempting to fit her subject to the contours of a compelling dramatic narrative, Bigelow gets bogged down in a strange and somewhat pernicious form of American exceptionalism. The movie is critical but essentially sympathetic; the script’s treatment of the U.S. as a reluctant nuclear power not only belies its actual track record but also narrows the movie’s focus to a fine and ultimately solipsistic point. Meanwhile, the lack of any larger geopolitical context—plus the coy refusal to ever specify whether the missile was fired on accident or as part of some larger, coordinated attack—works against there being any takeaway beyond raw, primal terror. As a result, Bigelow’s choice to elide any apocalyptic spectacle (much the way Lumet did in Fail-Safe) scans not as sophisticated restraint but as a high-handed cop-out: the opposite of Christopher Nolan’s stinger in Oppenheimer, which cut through time and space to grant its namesake a moment of terrible prophecy. A House of Dynamite is absorbing enough on its own terms, but it adds up to less than the sum of all fears or even of its own slickly moving parts. In trying to explore the gap between insanity and reality, Bigelow and her collaborators lapse into banality.