The heroes of One Battle After Another are revolutionaries who communicate in code. Bob Ferguson (Leonardo DiCaprio), though, has been out of the game so long that he’s forgotten how to speak the language. Sixteen years ago, in his previous life as a member of the revolutionary sect known as the French 75, our man walked the walk and talked the talk under the handle “Ghetto Pat,” a nickname that underlined his status as a white boy working with a clique of mostly Black operatives. His job was vaporizing office buildings at the behest of his lover and superior, Perfidia Beverly Hills (Teyana Taylor), a take-no-prisoners type who unapologetically got off on watching capitalist strongholds go up in flames. Now, the spark is gone. Bob has been reduced to dressing like the Big Lebowski and living in a Unabomber-ish cabin on the outskirts of the sanctuary city of Baktan Cross, listening to police scanners and doting on his daughter, Willa (big-screen newcomer Chase Infiniti). She’s resigned to his overbearing shtick, but just barely:

“Say it, baby,” Bob implores as Willa heads off with her friends.

“Love you, Bob.”

“Love you too.”

They both mean it, but he’s the one who needs to hear it.

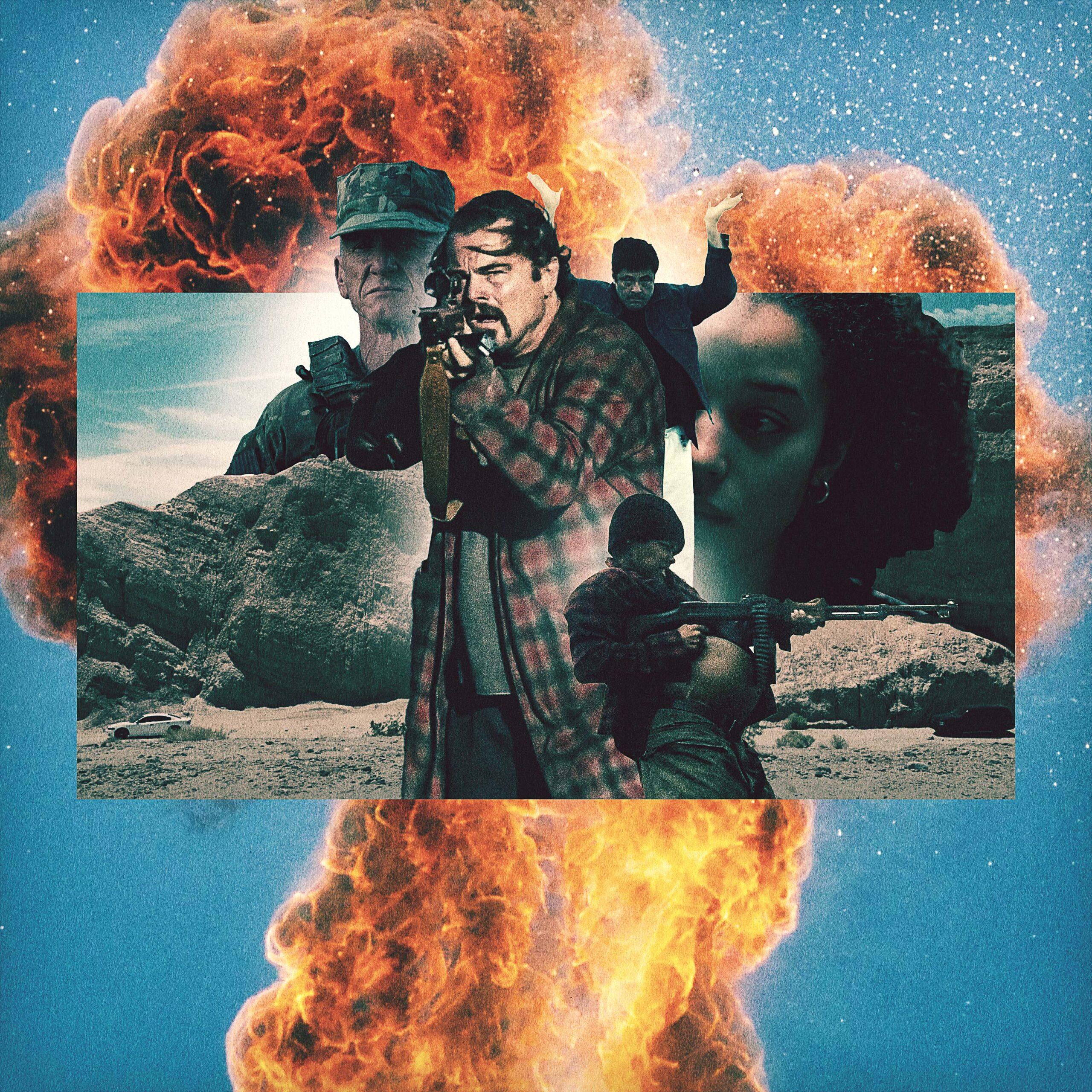

Willa was left in Bob’s care as a baby by Perfidia just before she was apprehended and blackmailed into snitching on her peers. Willa grew up believing her mother to be a martyr; in many ways, she’s Perfidia’s spitting image, not least of all in her insistence that she can take care of herself. Except that she can’t. Soon after arriving at a school dance, Willa’s snatched up by what’s left of the French 75 and taken out of town for safekeeping, far away from one Colonel Steven J. Lockjaw (Sean Penn), a high-ranking, xenophobic military man who previously managed to flip Perfidia by exploiting their perverse, clandestine situationship—a bad romance carried out under the noses of their respective factions—and the blood on her hands after a bank robbery gone awry.

Steven has his reasons for tracking down Willa. He wants to know whether she’s actually his daughter, a revelation that would threaten his long-desired initiation into a string-pulling, purity-minded white-supremacist cabal called the Christmas Adventurers Club (“Hail Saint Nick” is their motto). Descending on Baktan Cross with a team of ICE-style goons (and backed by a pricelessly unexpected musical cue), Steven is packing heat, as well as a mobile paternity test. He needs Willa alive, at least for now.

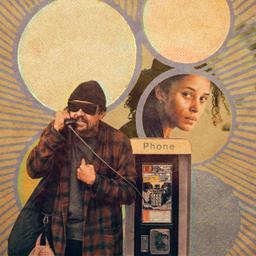

Bob, meanwhile, represents a more-than-acceptable level of collateral damage, not least of all because of the Colonel’s long-simmering jealousy toward him. Bob narrowly escapes capture and moves to regroup. Clinging to a supermarket pay phone, his eyes stinging with tear gas behind a pair of shoplifted sunglasses, he cycles dutifully, if impatiently, through the pre-set dialogue required to authenticate his identity and ascertain the rendezvous point with Willa and his friends. The spirit is willing, but the synapses, fried by a decade and a half of substance misuse, are weak. The voice on the other line wants to know what time it is; Bob’s recall of the magic word is drowned out by the sound of his own mind. What time is it? Does it matter? “I cannot remember, for the life of my only child, the answer to your question,” Bob rages. “Maybe,” the operator replies evenly, “you should have studied the rebellion text a little harder.”

One Battle After Another is a movie annotated by rebellious texts, integrating clips from The Battle of Algiers and needle drops by Gil Scott-Heron. In this way, it is the most explicitly political movie of Paul Thomas Anderson’s career by a desert-highway mile. It’s also, as indicated by its down-the-middle promotional materials and Fortnite crossover, an all-out action flick, overlaying its ideological intrigue and literary pedigree on a gleaming, gunmetal endoskeleton. The oft-quoted anecdote about PTA dropping out of film school because the instructor scoffed at the greatness of Terminator 2: Judgment Day has come home to roost. The set-up of two rival warriors—one good, one evil, both relentless—logging mutual mileage in pursuit of a leather-jacket-clad rebel who represents a future that is not yet set owes at least as much to James Cameron as Thomas Pynchon, whose 1990 novel, Vineland, is the movie’s source material.

As a work of adaptation, One Battle After Another is considerably less faithful than Inherent Vice even as it arguably surpasses its predecessor in channeling Pynchon’s sensibility—a vertiginous worldview perched on the bleeding edge and staring straight down into the abyss. “What is interesting is to have before us, at the end of the Greed Decade, that rarest of birds,” wrote Salman Rushdie in a review of Vineland for The New York Times in 1990. “A major political novel about what America has been doing to itself, to its children, all these many years. And as Thomas Pynchon turns his attention to the nightmares of the present rather than the past, his touch becomes lighter, funnier, more deadly.”

That One Battle After Another is superbly made is pretty much a foregone conclusion. It turns out that the answer to the thought experiment of whether a director already widely canonized for the consistent quality of his craft can handle the sort of massive budget more often handed over to hacks is—resoundingly—“yes.” The hype is real. There are sequences here so fluid and lucid—so controlled in terms of composition, cutting, and the hurtling, all-in sensation theorized by film scholar David Bordwell as “intensified continuity”—that remaining skeptics may feel obliged to bend the knee. The messaging is basically: Start polishing that overdue Best Director Oscar now or don’t give it out at all.

More interesting than the mesmerizing spectacle of Anderson’s flexing, though, is how a filmmaker so often defined (and, some would say, limited) by his own sense of nostalgia—by a tendency to retreat, to undertake Journeys Through the Past—has chosen, as per Rushdie, to deal with the nightmares of the present. In this context, the question that Bob struggles to answer, and upon which Willa’s fate rests, is less a non sequitur than a skeleton key, one that unlocks One Battle After Another beyond its bulletproof formalism and reliably excellent ensemble acting: What time is it? And do you know where your child is?

The passage of time, and the way it surpasses our ability to reckon with or control it, has become an increasingly central and affecting theme in Anderson’s work during the second half of his career, beginning with that staggeringly beautiful match cut in There Will Be Blood in which a small girl leaping off a porch in 1912 reappears in the frame 16 years later on her wedding day. Children grow up so fast, and while questions of inheritance and the combustibility of family dynamics are PTA standards—the building blocks of Hard Eight, Boogie Nights, and Magnolia, all of which are in some ways about the longing for a father—his later films probe these feelings from the tender vantage point of middle age and parenthood. They are revelations captured in a wide-screen rear-view mirror. The lost time in There Will Be Blood belongs to Daniel Plainview, whose collapse into murderous isolation is tied to his refusal to acknowledge or accept his adopted son’s autonomy. In The Master, Peggy Dodd can’t abide the thought of Freddie Quell as a surrogate man-child to her and her charlatan husband because of his lack of commitment to the family business, an empire built on carnival hypnotism masquerading as metaphysics. “This is something you do for a billion years, or not at all,” Peggy says disapprovingly to Freddie. In Phantom Thread, Alma fantasizes about living a thousand lives of her own with Reynolds and the infant Woodcock, their marriage a form of eternal return. “I can predict the future, and everything is settled,” she says, as if in a trance. The ambiguous ending of Inherent Vice, with Doc and Shasta only maybe back together, is offset by the emotional crescendo of Coy Harlingen’s long-delayed homecoming, a reunion made all the more affecting for being seen at a distance over Doc’s shoulder.

This yearning for reunion—for making up for lost time and attempting to wrangle it toward a happily-ever-after—was piercingly acute in The Master and Inherent Vice, both films made in thrall to Pynchon, with the former playing at times like a riff on V.’s discharged seaman turned cultist. They were also both about the search for a wayward and impossibly idealized female companion, a theme One Battle After Another complicates by sending Bob on a wild goose chase for the daughter to whom he’s devoted his life (if not his best self). In trying to retrieve Willa, Bob is seeking absolution, and maybe also a trace of his vanished relationship with Perfidia, who, as played with steely, hooded resolve by Taylor, may be the chanciest and most challenging of PTA’s obscure objects of desire. Her character, hugely altered (like all of the principals) from her model in the book, serves dually to embody female elusivity and a racially charged image of radical activism that gets exposed by a set of shifting and sexualized allegiances. Perfidia is a true believer who’s also a survivor; her hookups with Steven exist in an Andersonian tradition of power-gaming pillow talk, except tinged with the specter of radical chic, which in turn takes the movie into perilous rhetorical and representational territory.

That Anderson is a smart enough filmmaker to signal his own potentially dicey relationship to such material via Bob’s own awkward-white-guy status doesn’t necessarily mitigate it; like Ghetto Pat, he’s playing with fire. This aspect does, however, deepen the feeling of Bob as a rumpled and amusingly clumsy authorial stand-in whose particular set of skills is only of fitful use, a punching bag being put through the wringer and occasionally falling flat on his face—sometimes literally, as in a hilarious piece of staging that suggests The Dark Knight by way of Wile E. Coyote. The casting of DiCaprio—a Gen X Gatsby by way of Dorian Gray, whose Pussy Posse reputation precedes him—as a flustered, loving Girl Dad is a stroke of brilliance; ditto deploying Jeff Spicoli as an emblem of buzz cut authoritarianism and boomer selfishness, a villain determined to live long enough to see himself as the hero. Best of all, though, is Benicio del Toro as “Sensei” Sergio St. Carlos, Willa’s unflappable martial arts instructor and an agent of a more modest form of solidarity than the kind practiced by the French 75. He seems to have wandered in from Jonathan Demme’s humane cinematic universe. “Play defense,” he coaxes Bob over and over, leading his frazzled friend through a personalized extraction plan that dovetails with the evacuation of several dozen undocumented immigrants living under the sensei’s roof.

The contrast between his serene, on-the-move multitasking and Bob’s fulminations—heightened by his inability to find an outlet for his cellphone—is pricelessly funny, while the camerawork rhymes with (and surpasses) the stress-dream tracking shots of Punch-Drunk Love. Anderson’s gift for pent-up set pieces is legendary, as is his knack for finding unexpected, ecstatic points of release. The conditions demanding that Sensei and Bob play defense—the all-out, unstanchable assault on both vulnerable communities and individual persons of interest occurring on Colonel Lockjaw’s watch—are depicted in One Battle After Another with a mix of cartoon stylization and seething, incendiary realism. Midway through the film, a sequence depicting a standoff between a group of riot police and armed protesters in Baktan Cross is ignited by a shot of a crisis actor lobbing a Molotov cocktail from behind enemy lines. Whatever else you can say about a major studio investing over $100 million in this particular movie, the fact that this shot made the final cut reflects admirably on some executive.

On the one hand, presenting Steven and his fellow Christmas Adventurers as Saturday Night Live–style caricatures—complete with an extended cameo by the great SNL scribe/faux-Epstein associate/First Citywide Change Bank spokesman Jim Downey as a smiling, ruddy-faced power broker—could be taken as a juvenile cop-out, a refusal to engage with the actual gravity of the moment. On the other, the extent to which Vineland’s diagnosis of a nation’s rightward tilt—“restore fascism at home and around the world, flee into the past, can’t you feel it, all the dangerous childish stupidity”—has been recast as prophecy would seem to demand expressive treatment. And so, Anderson’s striving works like gangbusters, including and especially in a third-act car chase that finds PTA and cinematographer Michael Bauman using desert landscapes as hallucinatorily as Alejandro Jodorowsky—an eerie series of mirages set against a horizon that seems to recede the harder the characters push the pedal to the metal.

There is a school of thought, articulated by some of Anderson’s keener critics, that his reliance on unhinged spectacle to resolve his epically scaled movies—a shoot-out in a cocaine den; a hail of frogs; Philip Seymour Hoffman singing “Slow Boat to China”—is the artistic equivalent of a crutch, or an escape hatch. They won’t be mollified by the over-the-top tenor of One Battle After Another’s climax, but those of us who revere PTA as a purveyor of deceptively ambiguous grace notes—Daniel Plainview’s acknowledgment of his own exhaustion; Freddie Quell finally getting laid by a real girl while daydreaming of the woman made of sand on the beach; Alana deciding after a moment of crisis that she loves Gary Valentine after all—should have a field day with the coda.

At first, on the way out of my screening, I wondered whether or not the final scene, with its cozy evocation of domesticity after so much white-knuckle tension, felt tacked on or forced. With some reflection, the fragility of the optimism on display—the degree to which Anderson seems to be willing his big, scary state of the union address into a happy ending—is deeply moving. Not only does Bob finally know what time it is, he has a better idea of its true nature. Time is not a flat circle—not a thing to be predicted and settled, not a barrier to be broken. There’s no cause that’s going to last a billion years, not even close. More likely, [Daniel Plainview voice] we’re (almost) finished. All we can do is implore our kids to be careful—to play defense—as they head out into the breach and fight our battles for us, one after another, whether they want to or not. That’s the tour of duty that we’ve signed them up for. As for ways to pass the time, we could do worse than this light, funny, and deadly movie about what we’ve been doing to ourselves, and to them.