Back in January, film critics Manuela Lazic and Adam Nayman began working together on a long list that initially had more than 100 titles on it, in order to sum up something interesting—if not definitive—about the past quarter century of film. Narrowing things down was hard. They spread out their picks as evenly as they could over this 25-year period and also across a variety of styles, and throughout 2025, they will be dissecting one movie per month. They’re not writing to convince each other or to have an ongoing Siskel-and-Ebert-style thumb war. Instead, they’re hoping to team up and explore a group of resonant movies. We’re also hoping that you’ll read—and watch—along.

Adam Nayman: Is Kelly Reichardt the best American filmmaker of the 21st century? I realize this is a loaded—and leading—question, and also that she might not be the first name that jumps to mind. Such superlatives are usually reserved for certain directors in command of big-studio artillery. Reichardt, meanwhile, makes movies devoid of formal pyrotechnics—she just keeps fighting one small battle after another.

For the most part, it’s been an uphill grind. Her Malickian debut, River of Grass, aptly described by its maker as a “road movie without the road,” was shot for a pittance in the Florida Everglades and bowed at Sundance in 1994 at the dawn of a post-Tarantino epoch; at that point, there was probably about as much daylight separating Reichardt’s and QT’s iterations of “independent cinema” as existed between Pulp Fiction and Forrest Gump. A genuine rough-cut gem in a market of Miramax-coded zirconia, River of Grass was undervalued and tossed aside, after which it took Reichardt a decade to cobble together a feature-length follow-up. I first encountered her work in 2005 with Old Joy, a George W. Bush–era version of The Big Chill with Motown swapped out for Yo La Tengo. Its characters were countercultural warriors mourning their lost solidarity; when Will Oldham’s beautiful loser theorizes around a campfire about a “falling-tear shaped universe,” he was outlining the parameters of Reichardt’s all-American melancholy. Her connection to the New Hollywood of the 1970s is not a matter of camera movement or career path, but an honest and complex fascination with failure.

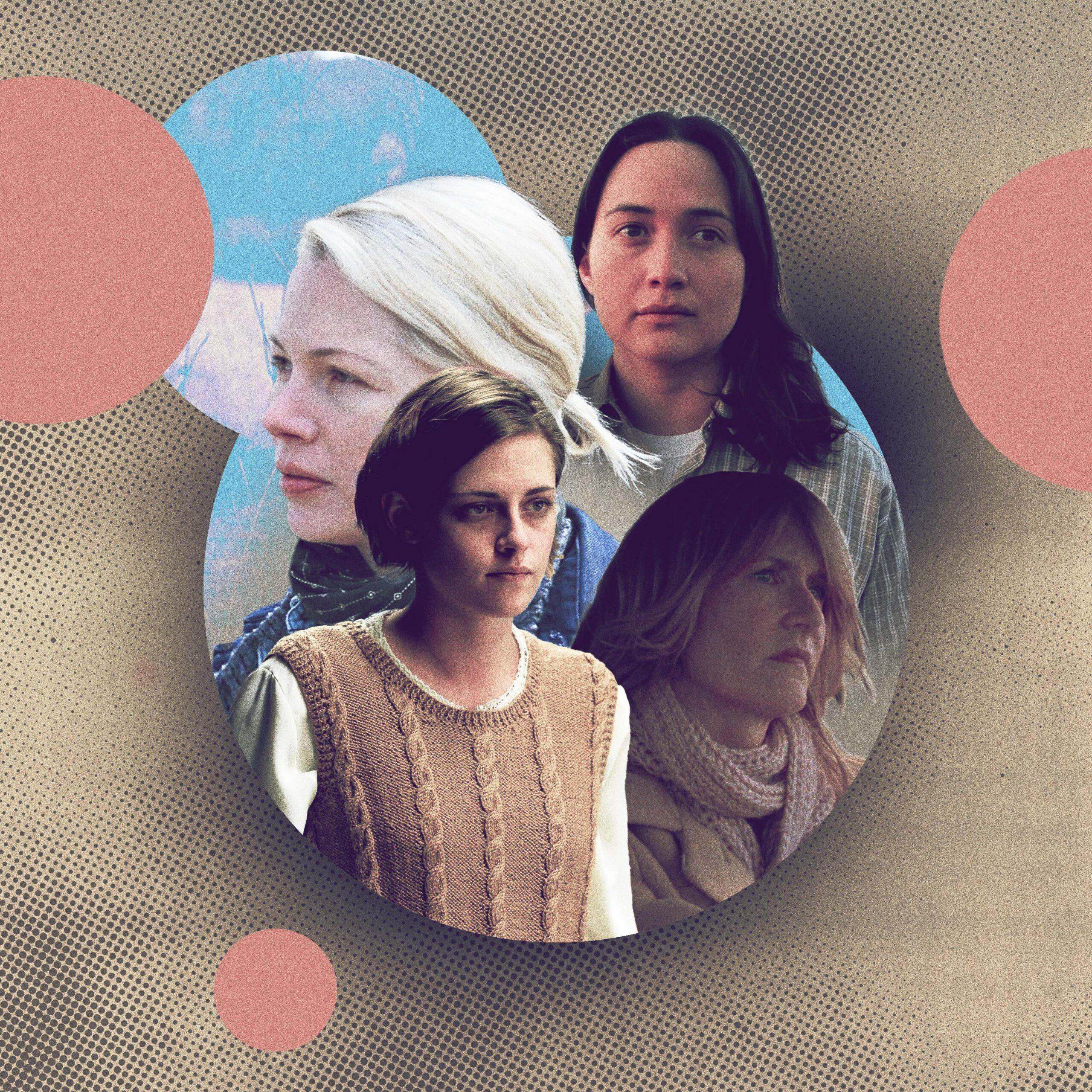

When you and I started making our long list for this project, we knew that Reichardt would make the final cut. I like that we settled on her 2016 drama Certain Women because it’s both exemplary of her style—a deceptively pressurized realism, alert to local color and flecked with humor—and also a bit of an outlier. For one thing, it’s the only one of her features other than River of Grass (and her upcoming The Mastermind) not co-scripted by Jon Raymond, the Oregon-based short story writer and novelist who is her most important regular collaborator. For another, it’s structured as a triptych, effectively doubling down on the miniaturism that is Reichardt’s signature. Its three stories, adapted from a book by Maile Meloy, are all set in the same place—Livingston, Montana, familiar to millions from Yellowstone—and connect in unexpected and unexpectedly glancing ways. Each focuses on a female protagonist trying to navigate their way out of some kind of personal, professional, or existential dead end.

I want to focus on a moment in the second episode that crystallizes so much of what I find special about the film and Reichardt’s cinema as a whole. The main characters in this section of the film are a couple, Gina (Michelle Williams) and Ryan (James Le Gros), trying to build a home outside the city. The logistics of the project—not only the cost, but the implications of opting out of urban living—have started redefining the terms of their marriage and co-parenting of their teenage daughter. (The fact that Ryan is having an affair, and that Gina knows about it, doesn’t help the situation.) One afternoon, they decide to stop by the home of Albert (Rene Auberjonois), an elderly homesteader whose property contains a valuable cache of sandstone that Ryan knows would make for solid building material—and which he suspects he can pry off the old-timer for less than it’s worth.

The long sequence where Gina and Ryan go into Albert’s home and squirm their way through small talk—exchanging wary, impatient glances that have as much do with their fraying intimacy as the matter of purchasing those blocks—is Reichardt at her best: a keenly observed comedy of manners featuring characters whose desires to live self-sufficiently belie their own weak spots, angst, insecurity, and hypocrisy. Ryan has no compunction about taking advantage of Albert’s hospitality; he wants him to think that they’re kindred spirits with similar ideas about working the land. But Gina, who’s got a one-track mind about the house, starts to have qualms. “I still have things to finish,” Albert says, and the look on Williams’s face as she recognizes the implication of that statement is devastating. He’s a man whose life is behind him, and besides her guilt over ripping him off—the better to create her own gentrified version of a home on the range—she catches a portent, perhaps, of her own future loneliness.

When Ryan and Gina go to leave, Albert walks them to the porch and points out a quail flitting past the pile of rocks; he mimics the birds’ call-and-response chirping. “How are you? How are you?” he warbles. “I’m just fine, I’m just fine,” Gina trills in response.

It’s a beautifully observed exchange—a humane moment of connection—but when Gina returns a bit later for her prize and gestures to Albert through his window, he simply stares back through the glass, which reflects the graying horizon over his face in a way that I haven’t been able to shake. He sees her, but he doesn’t wave back. He’s not just fine. It’s this sort of quotidian, death-tinged imagery—simple and direct but loaded with subtext—that makes me adore this filmmaker.

Manuela Lazic: I’ve now seen Certain Women four times, which is unusual for me, especially given how recent the film is. I find its slow, contemplative tempo oddly comforting, and the struggles of its characters endlessly engrossing. Like you said, they are all trying to deal with failure and dissatisfaction, yet Reichardt doesn’t pity them. Instead, she emphasizes their attempts at overcoming, or at least living with, their angst. She respects their turmoil too much to trivialize it.

The first section is the one that always mesmerizes me. With each viewing, my feelings about the dynamic between lawyer Laura Wells (Laura Dern) and her insistent client Will Fuller (Jared Harris) get more complex. Wells is frustrated with Fuller, who keeps turning up at her office uninvited and expecting her to suddenly offer a more encouraging opinion on his workplace injury lawsuit. Fuller is brash and ill-mannered, and it’s only when Laura takes him to see a male lawyer, who agrees with her, that Fuller accepts her conclusion. The first couple of times I saw the film, I understood Fuller as a simple misogynist who didn’t take women seriously even when they were trying to help him. Coupled with the film’s title—referring at once to a limited group of female characters and their certainty and strength, I thought, in a male-dominated world—I took the lesson, if there was one, to be that men expect women to help them because they believe they deserve it. Fuller isn’t simply dismissive of Laura: He also needs her, and not only for her legal expertise. As interpreted by Harris, Fuller looks at times like a little boy, making his decision to hold people hostage seem more like a tantrum in a bid for attention than a genuine threat. It is possible that Fuller wasn’t pestering Laura only out of sexist mistrust; he also wanted her to take care of him, or at least be there with him. There is still misogyny in his attitude, but Reichardt brings out the suffering and loneliness at its root, and challenges Laura’s certainty that her client was simply disrespecting her.

Reichardt may well be the best American filmmaker working today because she uses a clean, seemingly simple style to expose the full complexity of human feelings. She never takes any shortcuts, instead showing the most awkward and ambiguous moments that, together with more dramatic scenes, make up real-life relationships. In the film’s third section, set near Livingston in the township of Belfry, she makes melodrama in her own, realistic way. Instead of coming through glances full of longing or whispered confessions, the burgeoning and soon frustrated infatuation of rancher Jamie (Lily Gladstone) for Beth (Kristen Stewart) is expressed through the awkwardness she creates. She watches the education law teacher eat alone and just sits there, a discreet smile on her face. The most romantic moment in the episode is when Jamie arrives on her horse to take Beth to the nearby diner, yet even that gesture falls flat. Reichardt doesn’t ridicule it, but she also doesn’t elevate it above what it truly is: a misguided attempt at creating intimacy with a mostly indifferent love interest.

Reichardt’s anticlimactic style is also testament to her trust in actors. She knows that a face is the most beautiful and interesting landscape to shoot (in fact, as in the shot of Albert you described earlier, she grants as much importance to nature as she does to the people inhabiting it). The minutest changes in Michelle Williams’s behavior as both Albert and her husband give her grief register as seismic: We can sense her long history of marriage difficulties, and her fear of ending up alone like the old man. Since the film’s release, many have pointed out the way Stewart picks up her rolled-up napkin to dab her lips in that diner—although terribly brief and casual, it makes evident that Beth is always rushing, conscious of the four-hour drive waiting for her after the meal, not so concerned with her dinner companion. And yet, nothing in those performances feels predetermined for effect. Anchored in their characters and their circumstances, these actors are allowed to respond spontaneously to in-between situations, where the path forward is often obscure. Reichardt holds the camera on Gladstone for almost two minutes as she dejectedly drives back home before ending up in a field instead. Where do you go from there?

I wrote about Gladstone’s career-making performance in this film for The Ringer’s ranking of the 101 best performances of the 21st century (she got 23rd place), so I’d rather hear what you have to say about it. I also believe that Reichardt used Stewart’s unique skills better than anyone before or since. How would you characterize her perspective on and use of actors?

Nayman: Reichardt tends to get the most out of her performers: As much as she benefited from Michelle Williams wanting to work with her on Wendy and Lucy, she’s given Williams roles that make the most of her soulful qualities, and she coaxed a career-best performance out of Jesse Eisenberg in Night Moves. I agree completely with you on Stewart, who’s a wonderful actress within a particular range, and ideally cast in Certain Women as a reluctant object of desire. She’s at her best playing nervy, self-conscious characters who seem determined to burrow into themselves, and it’s this quality of flight-over-fight that makes her the perfect foil for Gladstone’s open-faced, open-hearted performance—which is absolutely one of the best of the last couple of decades. Her acting in Certain Women led directly to Martin Scorsese casting her in Killers of the Flower Moon, a movie with a second connection to Reichardt in the form of River of Grass star Larry Fessenden’s climactic cameo; when I interviewed Gladstone a few years ago, she gleefully observed that she’d gotten to play romantic scenes with both Stewart and Leonardo DiCaprio. It’s significant that Reichardt was the first director to cast K-Stew in a role with queer subtext, a year before the actress came out publicly on Saturday Night Live. Jamie’s attempted equine-assisted seduction is, as you suggest, a failure, but it’s also extremely sexy—a modest revision of classic Western iconography along similar lines as Brokeback Mountain, not to mention Reichardt’s own Meek’s Cutoff, in which an Oregonian wagon train gets commandeered and rerouted by a female protagonist whose toughness transcends the alpha-male posturing of her peers.

“We all know each other,” says one of Beth’s students during the first class. On the one hand, that line underlines the sense of Belfry as a tight-knit community, a place where folks are on a first-name basis with their friends and neighbors. But it’s also contradicted by our view of Jamie, who’s sitting alone in the back of the classroom, with several rows of chairs separating her from the other attendees. Jamie’s visible identity as a Native American woman rhymes directly with Laura’s observation in the first story of a young man in tribal dress ordering takeout Chinese at the mall—an image that’s almost a sight gag but for the way Reichardt uses it to convey a sense of mundanity. (Later on, we’ll see Jamie gazing at a cowboy ensemble in a shop window.) Even when she’s not being explicitly political—as she was in the eco-terrorist story Night Moves—Reichardt is attuned to social and cultural tensions and the way they get sublimated into the everyday. It’s telling that of all the things Beth and Jamie make small talk about, the latter’s background isn’t one of them, which in turn complicates Jamie’s arc of longing and abandonment at the hands of a noticeably uncertain woman whose act of ghosting is never explained yet feels inevitable all the same.

These pinprick sensations of regret—some glancing, some deep enough to draw blood—are Reichardt’s specialty, and they sit side by side with her underrated knack for comedy. I realize that so far we have not exactly made Certain Women seem like a laugh riot, but a lot of the scenes are quite funny, from the sub–Dog Day Afternoon chaos of Fuller’s hostage-taking—with Laura reluctantly descending on the scene in Kevlar like a combination of a cop, a lawyer, and a flustered mother—to Ryan and Gina’s bickering, to Beth’s Sisyphean account of commuting down icy highways between towns and jobs (“there’s cows roaming the road”). One of the reasons I liked Showing Up so much was that it found Reichardt doubling down on the deadpan sense of humor that doesn’t so much contradict the more mournful aspects of her work as deepen them; the fact that Jamie ends up drifting off—behind the wheel, and then off the road—into a rural pasture plays as slow-motion, metaphysical slapstick.

There’s an awful lot of driving in Certain Women: Laura’s longest exchange with Fuller happens while she’s giving him a lift; Ryan and Gina bicker constantly in the front seat of their station wagon; Beth and Jamie bond over their shared highway odysseys. Back when we wrote about Collateral, we discussed how important cars were to Michael Mann’s 21st-century worldview—a way for characters to recede from reality while moving through it. Going back to Reichardt’s assessment of River of Grass as a “road movie without the road" and thinking about all the vehicles in her other films, do you have any thoughts about the role of travel in Certain Women, or in Reichardt’s cinema in general? Or, more abstractly: What does it mean when a filmmaker seems so determined to stay in her lane?

Lazic: Comparing Collateral and Certain Women––maybe that’s what film criticism is all about. The first image that comes to my mind when you mention Reichardt's affinity for vehicles is the recurring motif in Showing Up of Jo (Hong Chau) parking her car with the stereo blasting in front of her house late at night, her headlights shining into Lizzy’s (Williams) adjoining garage, where the exhausted and irritated sculptor is trying to work. It’s at once a comedic touch and a subtly revelatory observation of the differences between these two characters: Jo prioritizes pleasure and herself, and finds a lot of satisfaction in her abundant creative output, while Lizzy is frustrated by everything and everyone and has to suffer to get anything done. Cars in Reichardt’s cinema are vehicles in more ways than one: They carry with them the hopes and anxieties of their owners. Everything starts going downhill in Wendy and Lucy when the car in which Williams and her dog are traveling to Alaska breaks down. As in Vittorio De Sica’s neorealist masterpiece Bicycle Thieves, the loss of this tool means economic struggle, but also a bone-deep kind of hopelessness. Traveling in Reichardt’s films is a way to try to get out of misery, but also a way to get lost. There really is no road.

I saw Showing Up only a few weeks ago, and I have to admit that it didn’t win me over then. But since, I’ve found myself thinking of certain moments again and again, and I haven’t been able to completely shake the unease that permeates it. In a film full of frustration and even cruelty (Jo really could take just a couple of hours to fix this goddamned boiler), there are sparks of joy and connection that still resonate: When Lizzy’s father, played by the always gregarious Judd Hirsch, takes the time to see all of her sculptures in the gallery, proud and awed, or when the wounded pigeon Lizzy rescued finally flies away without breaking anything. But I think it’s important to say that I probably wouldn’t remember these flashes of beauty so vividly if Reichardt hadn’t created this atmosphere of doubt and pain around them. She is not a sentimental filmmaker, but neither is she a pessimist. Rather, she is wise.

In truth, I had a similar experience of initial uncertain fascination with Certain Women. I couldn’t immediately put my finger on what I liked about it, or what drew me back to it. On my third viewing, four years after I first saw the film, I finally wrote that it was “mesmerisingly mundane … like one of those days when you’re especially sensitive and everything around you feels dramatic but in a good way.” It took me some time to find my own road through Reichardt’s attentive film; it had to percolate in my mind for a while before I could reap its secrets. I think this is why Reichardt is determined to stay in her lane. It’s a scarcely trod path, because its rewards aren’t obvious, and the line between “mesmerising mundanity” and plain banality is a thin one. But with each film, Reichardt continues her patient, painstaking work of searching for truth in our least glorious moments. Like many of her characters, she perseveres in the face of uncertainty to find glimpses of beauty.