The great Philip Seymour Hoffman once compared acting to “lugging things up staircases in your brain.” “I think that’s a thing people don’t understand,” he said. “It is that exhausting. If you’re doing it well, if you’re concentrating the way you need to, if your will and your concentration and emotional and imagination and emotional life are all in tune, concentrated and working together in that role, that is just like lugging weights upstairs with your head.”

After weeks of trying to put together this list, let me tell you that we feel the same about simply figuring out the best acting performances of our time.

What you have before you is The Ringer’s ranking of the 101 best movie performances of the 21st century. When we came up with the idea, we didn't realize how hard it would be to limit the list to that number. That means that a few of our favorites are missing—and assuredly some of yours, too. (Rest assured, PSH makes an appearance here—and very high up.)

After a few weeks of balloting, back-and-forth debates, and just overall list-shaping mechanics, we feel great about where this ranking landed. However, a few notes up top.

We had only one hard-and-fast rule: only one performance per actor on the final list.

That means that while we could’ve chosen a half dozen or so Hoffman performances—alas, there is no Along Came Polly—he has only one. We made this decision for two reasons:

- We wanted to put a stamp on the performances we felt were truly worthy.

- It allowed us to get some more interesting entries onto the list. Rather than loading it up with Cate Blanchett or Denzel Washington roles, we were able to get some smaller performances on here.

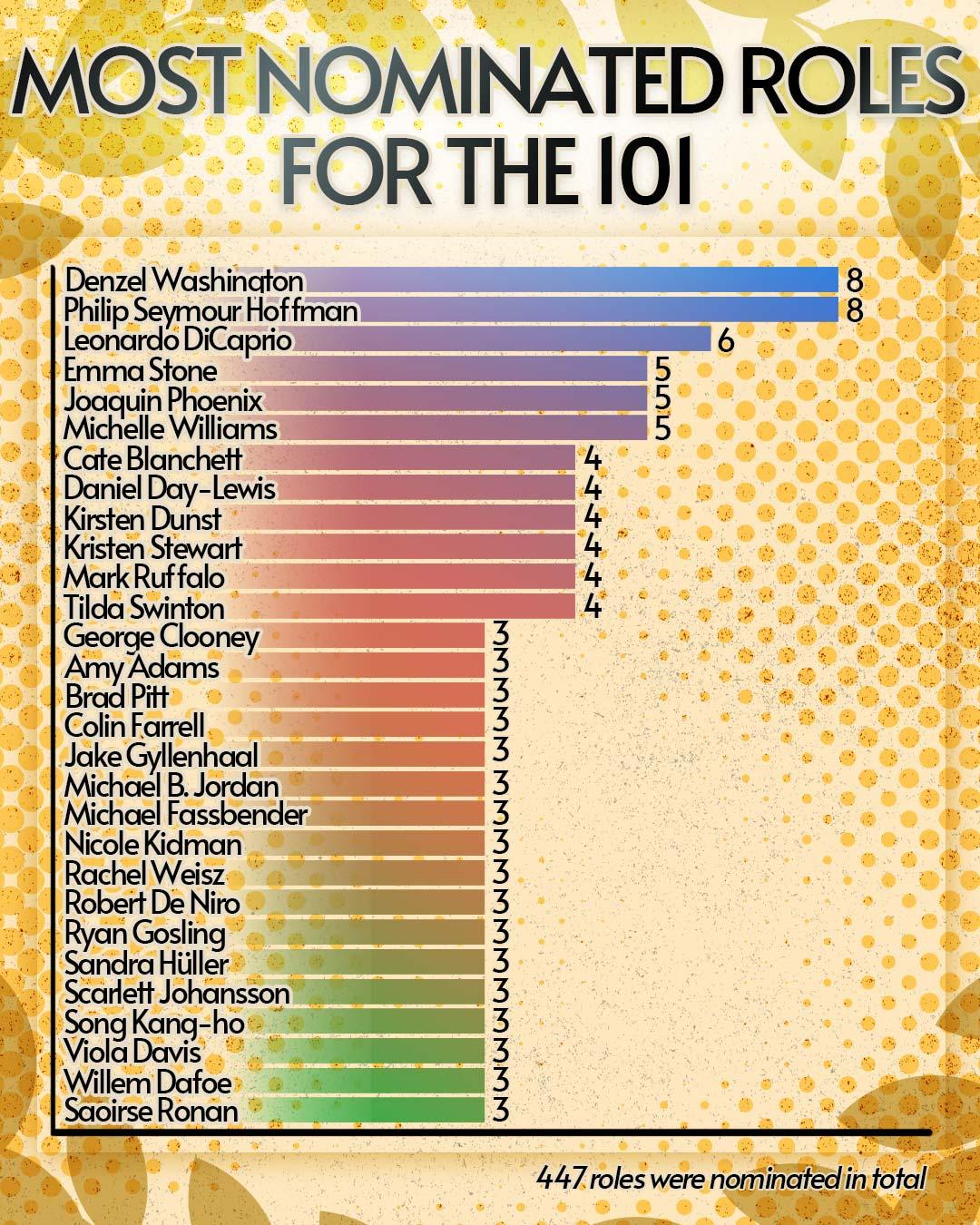

But while the final list had only one role per actor, the balloting process offered us many to choose from. Here’s the total list of actors who received votes for three or more performances from our committee:

Most of these actors landed a performance on the final list. A few, however, did not. You’ll have to read on to find out who.

There are only human performances—no animals.

This wasn’t a rule so much as a practicality. Look, I love Snoop from Anatomy of a Fall as much as the next cinephile, but it was hard to get Messi on here over, say, Julianne Moore. But if you say you want a list of the best animal performances, let’s just say, we’re listening.

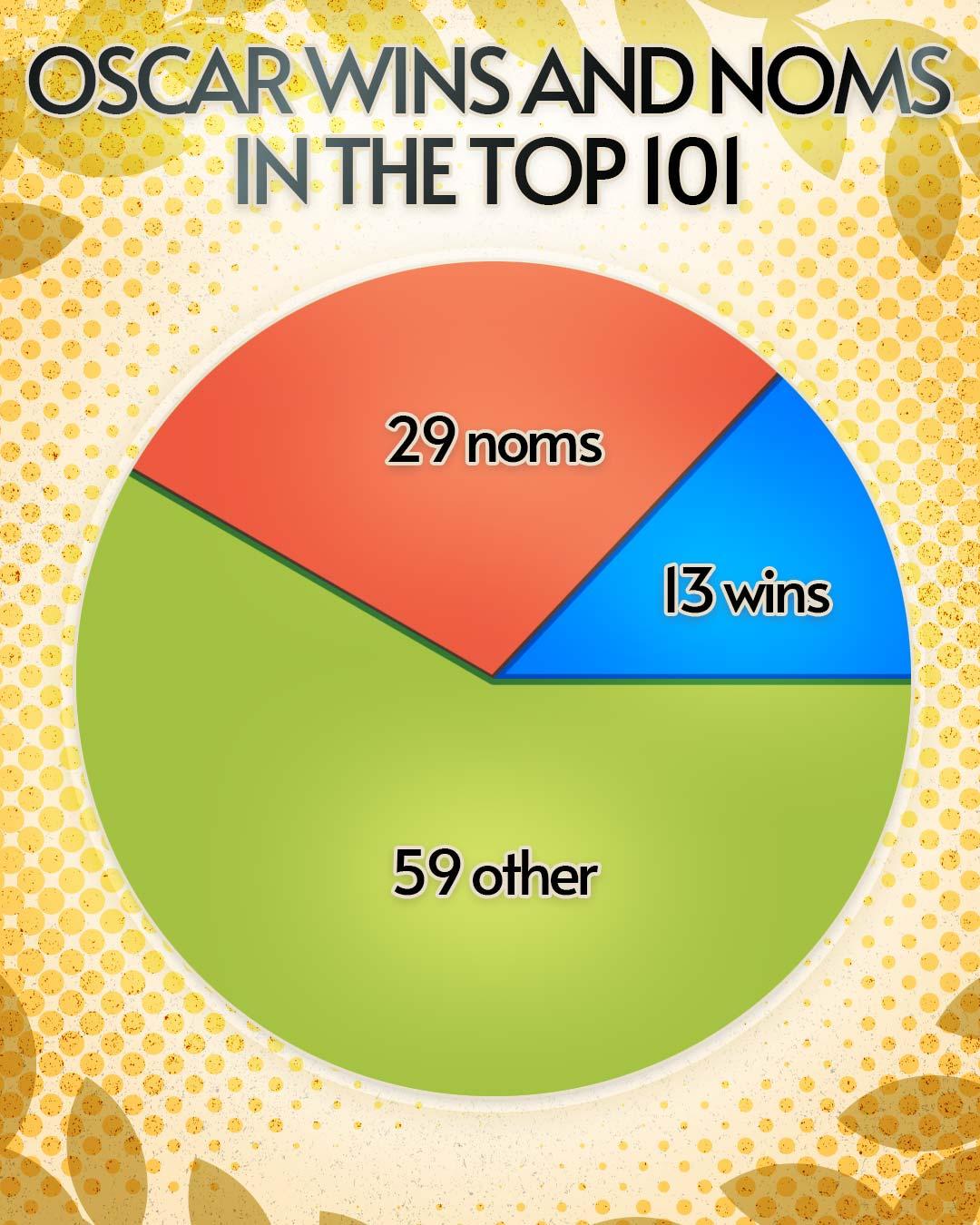

Oscar wins and nominations had little bearing on our end results.

Here’s a breakdown of our list by who took home the most prestigious hardware in Hollywood and who didn’t:

As you can see, nearly 60 percent of the entries below weren’t even nominated for an Oscar. That includes our no. 1.

In other words: Awards are cool, but we’re not gonna let them decide things for us!

Comedy matters.

The Naked Gun and Friendship may have proved this year that funny people still belong at the cineplex. But they never left the big screens of our hearts. I mean, you look at what some of these comedic actors are doing and tell us it’s not every bit as impressive as the prestige bait that racks up nominations.

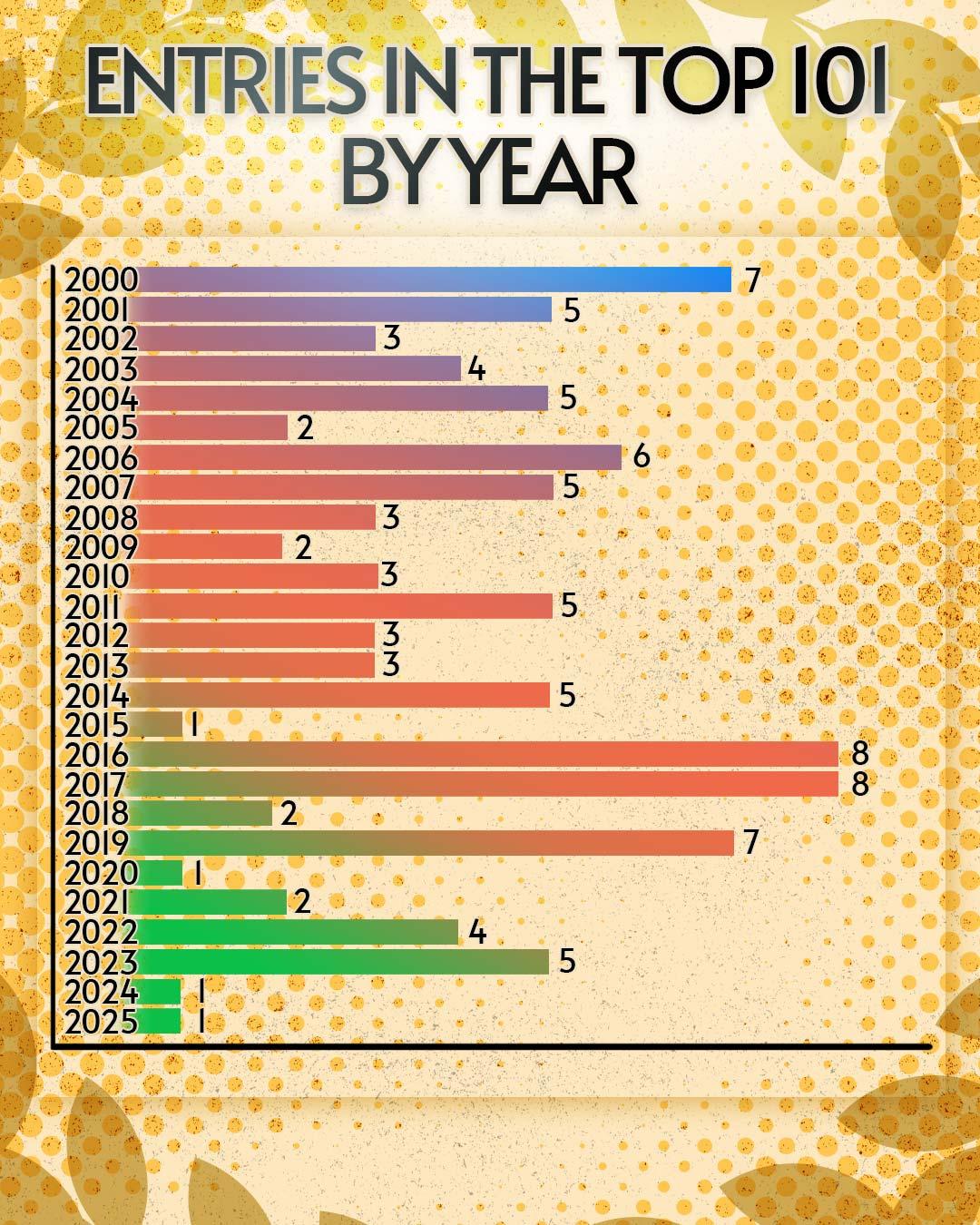

We expected to have some nostalgia bias, but …

Turns out the period from 2016 to 2019 was the most fruitful for our list. Here’s the breakdown:

2016 and 2017 led the way with eight entries apiece, while 2019 had seven. (We’re never gonna have a movie year like that one again, huh?) 2022 and 2023 also claimed four and five spots, respectively, which is in line with the best of the 2001-05 period. Even 2025 has a performance here—and that’s before the awards-season favorites begin to roll out in the next few weeks. (Again, not that those awards are gonna influence us or anything.)

So without further ado, let’s lug some things down the staircases of the brain and see how this all shakes out. And let’s start with an old favorite of The Ringer, both on the screen and on the court. —Justin Sayles

101

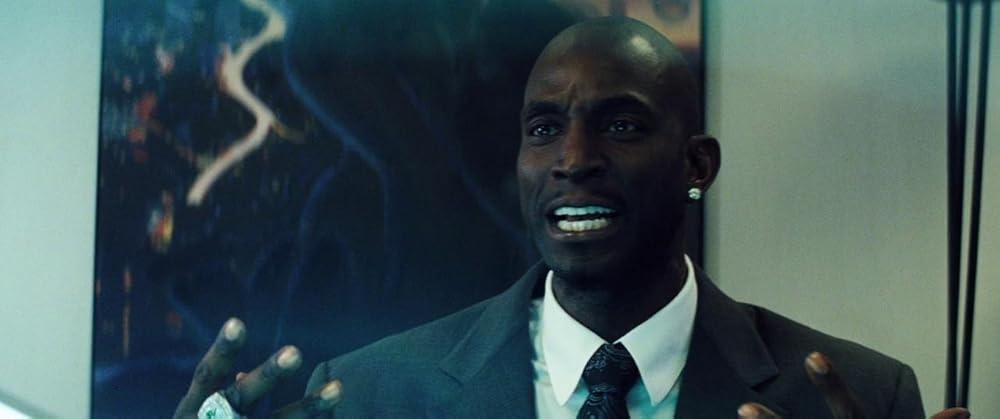

Kevin Garnett as himself, Uncut Gems (2019)

The most effective actors are able to convince an audience that what they’re watching is real. What performance? Every word you hear, every move you see, every speck of spittle that might as well span the screen and smack you on the cheek is 100 percent authentic, volatile, spontaneous energy. Anything can happen. Anything is possible.

Forget athletes—I don’t think anyone has ever “played” themselves with more comfort and authority than Kevin Garnett did in Uncut Gems. It’s simultaneously a revelation and exactly what would happen if a camera followed KG around the Diamond District on a spring day in 2012. Garnett’s brake-free intensity amplified the relentless boil of an atmosphere in which Uncut Gems flourished. “He’s incredible,” Josh Safdie said. “He tells stories in a way that’s so engaging. And it’s so three-dimensional in a weird way. He’ll set up where everybody was sitting, what was happening. Then he shifts the stories based on who’s paying attention. He’ll give it a shape. It’s like, ‘OK, this guy can act. That’s acting.’” On the surface, it all came naturally, which makes sense. For KG, natural is a performance. —Michael Pina

100

Ben Affleck as Nick Dunne, Gone Girl (2014)

Notoriously, Ben Affleck and David Fincher got into a bit of a Gone Girl tussle over Affleck’s refusal to wear a Yankees hat in the film. After a four-day shutdown, they compromised on a Mets hat, and Fincher called him unprofessional in his iconic DVD commentary. But Affleck wasn’t there to be a breeze—he was there to give the complex, enigmatic performance that only a man capable of being complex and enigmatic while juggling four Dunkin’ iced coffees could give. Author Gillian Flynn’s story of Amy and Nick Dunne was inspired by the real-life media coverage of Laci Peterson and the strange optics of her seemingly perfect husband Scott Peterson—who was ultimately convicted of her murder in 2004—and his grief … or lack thereof. The ultimate visualization of that eerie emptiness is Nick Dunne, who, though worshipped by the media and rubbernecking volunteers for his giant, handsome face, makes the strange, split-second decision to smile—nay, smirk—for a photo in front of his wife’s missing poster. When Fincher read that scene in the book, he could think of only one giant, handsome face to pull it off. Indeed, Affleck’s no-I-definitely-did-not-kill-my-wife look perfectly nailed the smarm-in-pursuit-of-charm—the mark of a performer using every tool in his occasionally tool-ish arsenal. —Jodi Walker

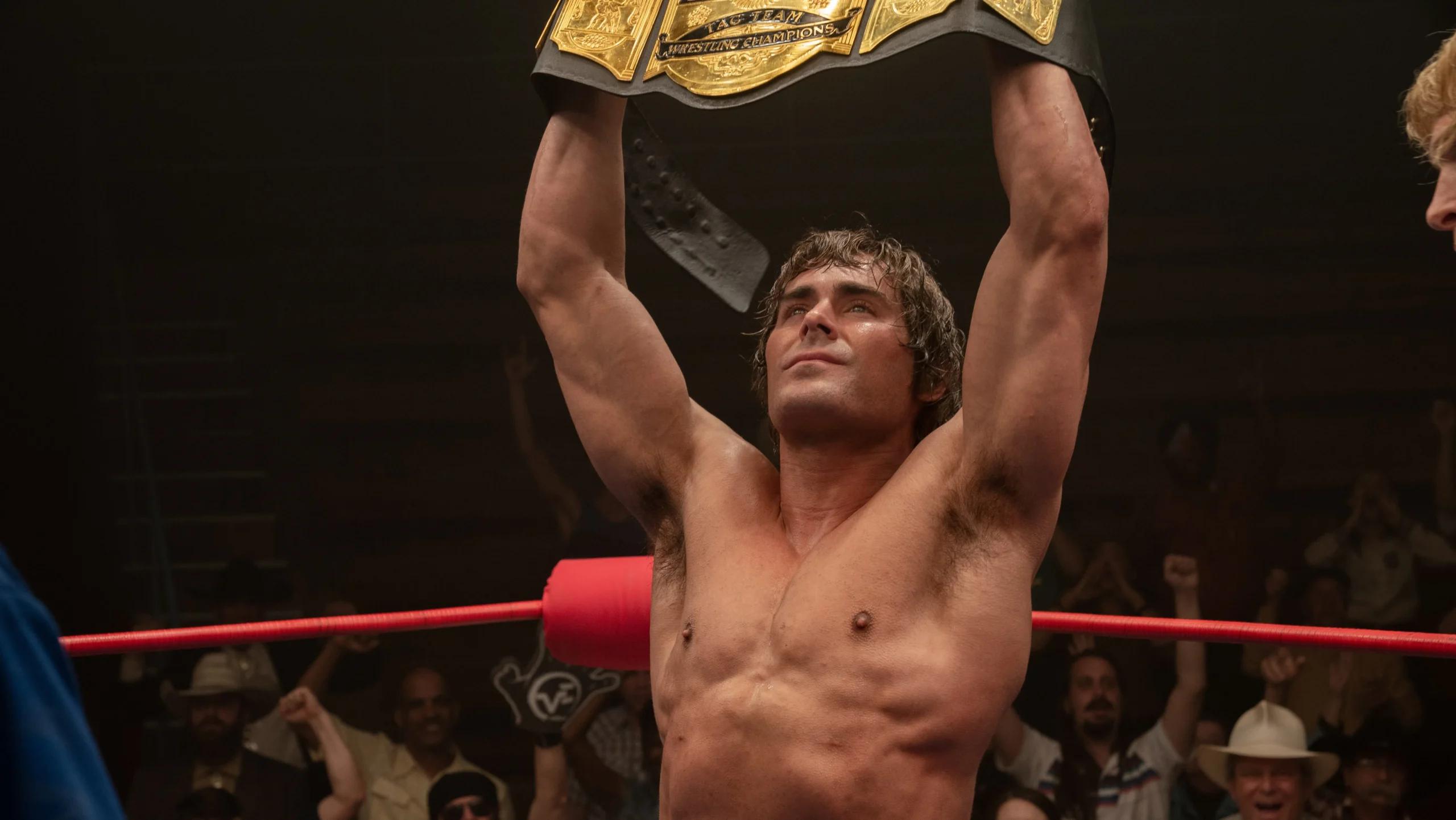

99

Zac Efron as Kevin Von Erich, The Iron Claw (2023)

Perhaps the final scene of the movie is enough of an argument? Sitting in his backyard as his boys run around, his brothers gone, reunited in the afterlife, Kevin Von Erich breaks into tears. The foundation of this moment of outpouring, of course, is two hours’ worth of simmer from Efron. It’s a career-defining turn in which the actor best known for High School Musical amplifies and shades his trademark charisma and pushes humanity, hope, and pain through a character who, by definition, is oppressed to the point of oblivion. Kevin is The Iron Claw’s center, and even going toe to toe with Holt McCallany, Harris Dickinson, and Jeremy Allen White, Efron never cedes that ground. The day I stopped believing in the Oscars was the day the Academy failed to nominate this performance. —Andrew Gruttadaro

98

Keke Palmer as Emerald Haywood, Nope (2022)

First of all, the dap. Second of all, the outfits. Keke Palmer’s Em Haywood enters Jordan Peele’s sci-fi-horror masterpiece Nope like a lightning bolt, rushing in as she’s late to the family business’s animal wrangler safety presentation on a movie shoot. Her eternally chilled out brother OJ (Daniel Kaluuya) is about to mumble his way through the spiel in her absence, but here comes Emerald to the rescue, absolutely demanding the camera’s attention. From her first moment, it’s clear we’re witnessing a master class in unbridled energy and pure magnetism (“I do a little singing on the side”). Sometimes you find an actor so charming, all you have to do is point the lens and let them cook. Just let her wax poetic about the Oprah shot and taunt a praying mantis with Sour Patch Kids. Of course, when things get serious, Palmer’s just as game to shift her tone—like when fear dances around her eyes as blood pours down on the Haywood home, or when she puts her back into turning the lever on a coin-operated wishing well camera to capture the perfect shot of Jean Jacket. But it all culminates in one last primal cry, a dispatch from her fiery spirit to claim victory on the foremost task at hand: Nobody fucks with Haywood, bitch. —Julianna Ress

97

Rachel McAdams as Regina George, Mean Girls (2004)

I want to be very clear that Rachel McAdams didn’t just originate the iconic role of Regina George in Mean Girls in 2004—she also originated the iconic role of Allie Hamilton in The Notebook two months later. And part of what makes the Regina performance such a marvel upon reflection is how completely different it is from the warm depth of Allie. Regina is as mean as she is charming, as compelling as she is revolting—and that complicated tightrope is walked perfectly by McAdams in a perfectly 2004 kitten-heel sandal. Mean Girls—with its teenage animal kingdom and occasional bus hits—is over-the-top at times, but McAdams’s Regina isn’t a caricature. She is a girl so cool, so captivating, so gifted in the backhanded compliment that you too would wear army pants and flip-flops or cut nipple holes in your tank top simply because it would get you closer to her. Likewise, from the moment I heard McAdams say, “Get in loser, we’re going shopping,” I knew I would follow her anywhere (even if just for the promise of one perfect line read) and that every teen movie would be chasing Regina’s giant devil-horned shadow for decades to come. —Walker

96

Robert De Niro as William King Hale, Killers of the Flower Moon (2023)

This is, it should be said from the jump, a messy construction. Love stories mined from annihilation. Put aside whether the foundations of Killers of the Flower Moon are faulty (I don’t believe they are) or whether the builder, Martin Scorsese, had all the right permits (I believe he did). Focus instead on this one section, this lone pillar. Few can claim the position that De Niro had, by the dawn of the century, solidified. This is not his best, but William King Hale—an architect of vicious destruction, wrapped up in folksy paternalism—is damn near close.

De Niro’s played unwell before. Murderous. Disturbed. But what he does in Killers is so subtly brutal, so altogether ordinary, so despicably banal, it nearly capsizes the film itself. You can’t stop looking at it. At his greatest, De Niro’s always been concerned with the American id, the darkest corners of our national consciousness. He mines it here. Pulls it out. Covered in blood. Picture clean. He’s never been more horrifying. —Lex Pryor

95

Jake Gyllenhaal as Louis Bloom, Nightcrawler (2014)

Lou Bloom is so slimy that I can smell him. Thanks to Jake Gyllenhaal, the psychopath with the slicked-back hair and a video camera is as, well, wormy as possible. Lou’s gross. But you can’t take your eyes off him—and not just because of Gyllenhaal’s good looks. From the first scene of the movie, it’s clear that this is a man who will do anything to make it. Gyllenhaal makes the character’s desperation, violent anger, warped sense of humor, and unscrupulousness feel very real.

Lou’s manipulations were so profoundly messed up that they eventually started to become funny to Gyllenhaal. During filming, he and the movie’s director kept cracking up. “Dan Gilroy and I were laughing pretty much the whole movie,” Gyllenhaal told MTV in 2014. “We knew we kinda landed on it when we'd finish a take and bust up laughing." —Alan Siegel

94

Charles Melton as Joe Yoo, May December (2023)

There is an argument to be made that Charles Melton’s Joe, rather than Natalie Portman’s Elizabeth or Julianne Moore’s Gracie, is the protagonist of May December. Todd Haynes’s fictionalization of the Mary Kay Letourneau scandal follows Elizabeth as she spends time with Gracie and Joe while preparing to portray the former in a cheap docudrama about the student-teacher relationship that made tabloid headlines and survived Gracie’s incarceration. We see Joe’s teenaged children clock his emotional age as being younger than theirs; we follow him as he seeks an illicit connection with someone his own age and is flummoxed by the contours of adult relationships. He and Gracie are both flailing, but her obvious maladjustment (and the uniform skepticism about their marriage) forces him to sublimate his. Melton makes sure it ripples just beneath the surface. —Paul Thompson

93

Mark Wahlberg as Sgt. Sean Dignam, The Departed (2006)

The role any actor was “born” to play is a trite compliment that doesn’t typically mean anything. But for Mark Wahlberg, Sergeant Dignam is absolutely the role he was born to play—an unforgiving, overconfident Masshole whose pitch-perfect Boston accent goes hand in hand with the bullshit detector he unleashes on everyone else in the movie. Every line is good for a laugh. Every line heightens the scene’s intensity.

It’s the only Oscar-nominated performance of Wahlberg’s career. It’s also, arguably, his best: a portrayal that allows him to toe the line between being the perpetual butt of every joke and a roast-master general. In a movie in which just about every relevant character is two-faced and living a double life before they die, it’s not a coincidence that Dignam—through and through true to himself as an arched-eyebrow skeptic—gets to be the last man standing. —Pina

92

Kate Winslet as Sarah Pierce, Little Children (2006)

By 2006, the suburban ennui comi-drama had become a little passé. In the liminal space between the start of two U.S. wars in the Middle East and the burst of the housing bubble, the idea of “horny but bored well-to-do married people try to feel alive” seemed like the domain of previous era, when American Beauty somehow won Best Picture and Happiness seared a mark on the soul of anyone who watched it. (The latter is a compliment, by the way.) So it’s largely a testament to Kate Winslet’s work in Little Children that Todd Field’s second feature manages to transcend those trappings. She plays something of a 21st-century Emma Bovary, smoldering in her protests against her own life, making her adultery seem like an act of revolution. As Sarah Pierce, she alternates between assured (kissing Patrick Wilson’s would-be skater dad without a care about who sees it) and desperate (watching her affair partner like an amateur PI) before snapping back to reality at the film’s close. But the fact that she was able to take us outside that reality at all is why this performance still resonates. —Sayles

91

Léa Seydoux as Gabrielle, The Beast (2024)

I can still hear that scream. It’s the most viscerally upsetting movie ending I’ve seen since Mulholland Drive (which it feels of a piece with). Léa Seydoux’s Gabrielle is coming down from a mind-bending procedure through time in an attempt to “purify” herself by eliminating her pitifully human emotions in a society taken over by AI. The procedure doesn’t take, so she’s stuck with the darn things anyway. She encounters her generational soulmate (or maybe her perpetual death knell) in Louis (George MacKay), believing this is finally the timeline in which they get to be together. But his coldness and glazed-over eyes reveal it all: He’s undergone the procedure, leaving him emotionless and, crucially, unable to truly love. It’s there that Gabrielle cries out in anguish—not just for the loss of Louis, but for the curse of having a heart in a world that’s surgically extracted its own.

Seydoux’s stoic exterior has made her suitable as an icy villainess in Mission: Impossible or as a frequent member of Wes Anderson’s cast of stilted characters, but in Bertrand Bonello’s The Beast she both inverts that quality and pushes it further. Her outward apathy masks a person who feels deeply and tragically, and try as she might, she has never been able to outrun her humanity, all the way from 1910 Paris to 2014 Los Angeles to a 2044 AI lab. That scream is the culmination of it all—the realization that she’s doomed to a cycle of pain, to unfulfilled love, to simply feel forever. It’s still ringing in my ears. —Ress

90

Bill Murray as Bob Harris, Lost in Translation (2003)

No awards show snub in world history—forget the Grammys, the Emmys, the Pulitzers, or the VMAs—hurts worse than Dr. Peter Venkman not getting the Oscar here. It would’ve been a guaranteed all-time-great acceptance speech: a beloved and galactically mercurial comedy superstar finally getting the institutional respect he deserves. But Lost in Translation is so much more than a comedian-gets-serious prestige power play: Bill Murray wonderfully trudges through Sofia Coppola’s moody and complicated masterpiece (though much of the comedy has aged horribly) with an electric combination of dignity and resignation, resilience and exasperation, sage wisdom, and total bewilderment. Murray’s performance, by contrast, has aged beautifully precisely because his character is aging before our eyes so tumultuously—a downward spiral communicated entirely through the hilarious deflation in his eyes, the micro-slapstick slump of his shoulders, and the concussive power of his final cryptic whispers. You spend the whole movie hyperconscious that you’re watching Bill Murray, comedy legend, but that only pulls you even deeper in rather than pushing you away. He throws his weight around while barely moving a muscle. —Rob Harvilla

89

Colin Farrell as Ray, In Bruges (2008)

Storming onto the scene right at the start of the century with that sexy olive skin, those thick eyebrows, and an even thicker Irish brogue, Colin Farrell spent a few years being improperly typecast as a pretty-boy straight man until Martin McDonagh saw what he truly was: a really handsome character actor. Enter Ray, the younger of two hitmen sent to hide out in Bruges after a botched job. We buy that he could kill a guy, and that he fucking hates Bruges, but Farrell brings a puppy-dog sincerity that offsets the brashness. That’s key particularly for early McDonagh works, which often take undue pleasure in discomforting amounts of giggling at minorities and un-PC indulgences. Even so, the sheer delight with which Farrell exclaims them is, unfortunately, irresistible. That disarming naivete feels like a strictly comedic choice until you realize this is a character whose defining trait is a severely wounded fragility. The film is haunted by the prospect that any little boy is one “wrong place, wrong time” away from becoming a victim, but perhaps none more so than Ray—lost, bewildered, and wondering how he wound up here, a murderer, surrounded by dead bodies, in fucking Bruges. —Kyle Wilson

88

Simon Rex as Mikey Saber, Red Rocket (2021)

Sean Baker has made a career off of willing magnificent performances out of first-time actors, from Kitana Kiki Rodriguez in Tangerine to Bria Vinaite in The Florida Project. In Red Rocket, however, he sought to revitalize a career rather than create one. Simon Rex got his start in porn before taking on a few Scary Movie sequels and then making a move to comedy rap under the name Dirt Nasty (“1980” went platinum on my iPod, don’t judge me)—career choices that don’t exactly indicate a path to prestigious film roles. Baker thought otherwise. After Rex’s work prospects had largely dried up, the director reached out to him for the part of Mikey Saber, a washed-up porn star and preeminent scumbag who returns to his small Texas hometown to take advantage of everyone in sight. And it couldn’t have been a more perfect choice.

Rex wasn’t just the ideal man to take on Mikey because of his shared background in adult entertainment—though his familiarity with the type of guy Baker was aiming for certainly helped. He also has a ridiculously magnetic charm that, in hindsight, is clearly apparent in his 2000s comedy work and is used to all-too-familiarly enable a charismatic swindler who somehow keeps getting away with it in Red Rocket. You wince as you watch Mikey talk his way out of jam after jam, leaving literal wreckage in his wake, but you know you’d probably get duped by him all the same if you had been there. It’s a stunning performance that not only revived Rex’s career—lucky for us, he’s maintained steady work since Red Rocket’s release—but provided a truly singular portrayal of the real-life paradoxes that walk among us every day, yet are rarely captured on-screen. —Ress

87

Willem Dafoe as Thomas Wake, The Lighthouse (2019)

To my friend Tom, I’m fond of yer lobster. I’m fond of just about everything Dafoe is cookin’ in Robert Eggers’s black-and-white stunner The Lighthouse. Dafoe’s Thomas Wake is a goddamned drunken, horse-shitting genius. He is a weather-beaten sailor with 13 Christmases at sea, now damn well wedded to the light. He’s a wickie, and a wickie he is—charcoaled black and gray, an old, grizzled crustacean limping twixt storm and stone. One moment he’s a dancing buffoon; the next, he’s cursing Neptune in a rolling, tidal rage: “Hark, Triton, hark! Bellow, bid our father the sea king, rise from the depths, full foul in his fury, black waves teeming with salt foam, to smother this young mouth with pungent slime.”

Dafoe steals the screen with piss, farts, and Shakespearean monologues. It’s blunt and poetic. Grotesque and beautiful. Full of inescapable dread and unbridled cheer. Dafoe is somehow the calm and the storm. It’s arguably his career-best performance, and by God and by golly, I watched it smilin’. (’Cause I like it. And I like it ’cause he says I do.) —Austin Gayle

86

Florence Pugh as Dani, Midsommar (2019)

Sometimes, an actor saves their best work for when their characters are put through the wringer. By Florence Pugh’s own admission, she “abused” herself in Midsommar to get into the headspace of Dani, a college student reckoning with her entire family being killed before vacationing with her boyfriend (Jack Reynor) in rural Sweden. (Midsommar is also a very tough beat for Sweden’s tourism board.) Like Toni Collette in Ari Aster’s previous film, Hereditary, Pugh projects so much suffering from Dani’s ordeal, exploring the damaging ways in which people try to heal from their grief and trauma. There’s a ton of screaming, a ton of crying, and finally, a twisted form of catharsis featuring a bear carcass (if you know, you know). From start to finish, Midsommar is an emotional roller coaster, which makes you appreciate the lengths Pugh went to even more. That Pugh wasn’t recognized by the Oscars for her troubles is enough to make me go full Hårga. —Miles Surrey

85

Viggo Mortensen as Tom Stall/Joey Cusack, A History of Violence (2005)

Really, we could have gone with any of Captain Fantastic’s collaborations with David Cronenberg. They’re clearly BFFs and artistic soulmates, and they consistently bring out the best in each other on the red carpet and in their work. But there’s something about the sleight of hand in Mortensen’s acting in A History of Violence that makes his performance as Tom Stall first among equals.

Cronenberg’s graphic novel adaptation turns on the mid-film revelation that Tom—a small-town family man beloved by his wife and kids and the patrons at his diner—is hiding a sinister backstory: He’s actually “Crazy” Joey Cusack, once the scion to an organized crime empire, now on the lam from his kingpin brother. Technically, this is a plot twist, but when you watch A History of Violence carefully, it’s clear that Joey Cusack has been there since the beginning. Tom Stall is a bad man’s impersonation of a good man: half aspirational, half alien, and as fully Cronenbergian a creation as Jeff Goldblum’s insect-human hybrid, Brundlefly (whom Stall resembles when it comes to mutilating his enemies).

The long centerpiece hospital room sequence in which Tom slowly comes clean to his wife, Edie (Maria Bello)—“I wasn’t really born again until I met you”—is pricelessly funny for the way Mortensen evokes an apex predator whose skin has slipped and is now exposed, out of his element, and trying to adapt. The Darwinian comedy of the film’s climax, meanwhile, gives the former Aragorn a fine showcase for some survival-of-the-fittest ass kicking and serves as a reminder—along with the bathhouse brawl from Eastern Promises—that our guy could have easily been a weathered (and wealthy) Hollywood action hero, except that he’s too much of a weirdo. Kudos, Viggo. —Adam Nayman

84

Ryan Gosling as Ken, Barbie (2023)

[“Also Sprach Zarathustra” funk remix playing]

Gosling’s in the pocket on arrival here, so ready to play. Ken’s a character that wears his inner turmoil on the outside of his person. The Goz deadpans the absurd, leans into the foolishness. It is deeply felt himbo duncery, a man throwing himself headlong into dumb. Bless his heart. Ken’s love for horses just pushed him too far. We can all relate.

He wears slights like a teenager, all fury and embarrassment. Ken swings wildly from cocky to jealous to sad to insecure to happy to confused. At no point is there anything resembling a false note. One of the funniest performances this century. When he’s walking in Century City for the first time, Ken could not be feeling himself more. The wonder on his face when he sees a Hummer for the first time, copying businessmen’s finger wags, reveling in the fur-coated images shining before him. Pure elation on his face. It’s like watching someone try ice cream for the first time. He did not know joys like these were possible, and now he’s drunk off new possibilities.

[Glitter chiming]

There is just no note out of place here. A lesser actor, the fur wears the man. Gosling can wear a floor-length mink hanging off his shoulders and do old-school boxing-style punches while singing the words “fight for me,” and it’s just pure, weapons-grade star wattage. So much fun. Every laugh he goes for, he gets. There’s no holding back here. He comes riding into the scene, Holy Grailing it atop an invisible steed, complete commitment to the bit. —Tyler Parker

83

Tiffany Haddish as Dina, Girls Trip (2017)

Fact check me on this, but: I believe this is the only performance on the list in which the actor says, “I got drugs in my booty.” Girls Trip was the surprise hit of 2017, and Tiffany Haddish crashes into it like a tornado. As Dina, she steals every scene she’s in. Every line delivery is deserving of a Funkmaster Flex bomb drop. The performance is massive in scale, yet Haddish is never not in control. There was serious Oscar buzz for this performance—do you remember that? When Haddish was snubbed, people were legitimately mad. (That year’s Best Supporting Actress category was actually sort of loaded; had Girls Trip come out a year later, she probably would have at least been nominated.) But all of that enthusiasm was extremely deserved: Haddish gives this performance everything, so much so that it’s almost as if Dina—and that Oscars season, including the dress Haddish wore multiple times because “I paid money for this!”—is still looming over Haddish’s career. No matter what, though, she’ll have this legendary turn. —Gruttadaro

82

Renate Reinsve as Julie, The Worst Person in the World (2021)

Unlike many of the performances on this list, Reinsve’s isn’t particularly theatrical or showy; it’s mostly quiet and moves like real life, gradually changing as she gets older and painfully wiser.

Her character, Julie, doesn’t quite know what she’s doing with her life. That’s the central, relatively understated conflict of The Worst Person in the World. And even though Reinsve is in full control of her performance, you believe her as someone who doesn’t always know what to do. When she’s arguing with a boyfriend, her frustrations and hurt spill out almost unintentionally; when she’s falling in love with someone new, she can’t keep her eyes off them; when she’s trying to hide how she feels, she lets just enough anger or hurt show that we can read her, as if she’s a good friend we’re watching from across the room. Throughout the movie, Julie is in the process of discovering herself—both eliminating the things she doesn’t want and then coming back once she realizes she needs them. Reinsve also seems to be in the process of discovery, surprising herself, and us, with what she finds and who she can become. —Helena Hunt

81

Jim Carrey as Joel Barish, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004)

Ace Ventura has never gotten his Oscar, alas; he has settled instead for being Two-Time Golden Globe Winner Jim Carrey. Did he deserve one for playing Andy Kaufman? Maybe. Did he deserve one for playing Truman Burbank? Probably. But Lord Jim did his best-ever work in Michel Gondry’s bleak, whimsical, chaotic, and heartrending 2004 tragi-romantic fantasia, precisely because the funniest (arguably) and hardest-working (inarguably) comedy superstar of his era doesn’t try to match either the whimsy or the bleakness.

Carrey doesn’t overact, and he doesn’t overact by underacting the way most prestige-hunting comedians do. Instead, as Joel—the soft-spoken introvert, the nice guy, the red-flag-waving “nice guy,” the heartbreaker, the heartbroken—our man plays everything masterfully straight, affable, and potentially lethal, with his most devastating (and romantic!) lines delivered as casual asides. “I remember that speech really well,” he whispers; “OK!” he concludes, with a shattering, tossed-off charm that wins over both Kate Winslet and several subsequent generations of hopeless (and devastated!) romantics. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind’s high concept and higher melodrama would’ve swallowed up both lesser and harder actors; Jim Carrey, here and maybe only here, delivers an absolute masterpiece of perfect balance and total control. Against your better judgment (and possibly his), you will fall for him again, every time. —Harvilla

80

Margot Robbie as Nellie LaRoy, Babylon (2022)

You can measure Robbie’s raw power by how many of our greatest working directors just put her in frame and let her cook. Tarantino. Gerwig. Scorsese. It’s the cheat code of contemporary filmmaking. Yet no one has harnessed Margot’s presence on-screen quite like Damien Chazelle, who structured a whole-ass epic around her talent for cut-to-the-core expression. The rapture, the ecstasy, the malaise, the indignation, the misery—everything Babylon is and wants to be is right there on Robbie’s face, as we spend the better part of its three-hour running time watching the twinkle in her eye slowly fade away.

Plus, y’know, the projectile vomiting, and the high-wire choreography, and the note-perfect physical comedy. Babylon is unapologetic in its want to have it all. One of the ways to accomplish that is with a dazzling ensemble. Another is to center a performer who can do anything and everything. Babylon calls its shot on Nellie being a star, but Margot makes it so. She makes the smallest emotional beats feel enormous and the grandest productions somehow intimate. She ties the sprawl of an enormous movie together, even as it constantly threatens to teeter out of control. Maybe Babylon is guilty of overreaching. Yet when Robbie is delivering fireworks on every front, can you really blame it for its ambition? —Rob Mahoney

79

Renée Zellweger as Bridget Jones, Bridget Jones’s Diary (2001)

You don’t often see actors traveling east across the Atlantic for a movie role. Even less often do you see it work. But Renée Zellweger (originally from Katy, Texas) as the British Bridget Jones is magic like that. A modern retelling of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice—with Bridget as the stand-in for Elizabeth Bennet—Bridget Jones’s Diary rests entirely on Zellweger’s shoulders, and not just because she pulls heavy duty as a voice-over narrator. Zellweger is sympathetic, delightfully raw, and, most importantly, funny. She turns herself into the ultimate everywoman, exposes herself in unthinkable ways, and comes out on the other end on top. Before Bridget Jones’s Diary, Zellweger was known for playing mousy, deferential characters in movies like Jerry Maguire and Me, Myself & Irene—to say that no one saw this coming would be an understatement. But there’s a reason that, almost a quarter century later, she’s still playing this character in movies rather than any of those characters. —Gruttadaro

78

Kristen Stewart as Maureen Cartwright, Personal Shopper (2016)

Imagine telling someone in 2008 that the two leads in Twilight would do their best work in the art house scene. But just as Robert Pattinson has become one of cinema’s preeminent weirdos (complimentary), Kristen Stewart emerged as an actress most in her element playing someone uncomfortable in their own skin (complimentary). Case in point: Olivier Assayas’s genre-bending Personal Shopper, in which Stewart plays Maureen Cartwright, a supermodel’s personal shopper (!) who is also an amateur medium (!!) trying to contact her twin brother from beyond the grave (!!!). But while Personal Shopper features an actual ghost and a bloody crime scene, Stewart’s finest work comes in moments of relative stillness: Maureen sifting through exorbitant outfits, watching art history videos on YouTube, exchanging texts with a sinister presence. Stewart conveys a quiet yearning throughout as Maureen is, rather fittingly, caught in an existential state of purgatory—waiting for a sign for her brother, and for life in the mortal realm to still give her meaning. All in all, Personal Shopper is right in Stewart’s wheelhouse, and just like her Twilight costar, she sparkles. —Surrey

77

Adam Driver as Paterson, Paterson (2016)

The protagonist of Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson, named Paterson, works in Paterson, New Jersey, as a bus driver, and is interpreted by Adam Driver—a lot of pleasing echoes for a film about finding poetry in the everyday. In his spare time, Paterson writes poems that only his wife (Golshifteh Farahani) ever reads, and the regular pattern of his life repeats day after day, the only variations coming from the conversations he overhears on his bus rides. With his striking physicality and direct, unvarnished manner, Driver anchors the film in the physical world, making his character’s preference for all things tangible and his rejection of digital technologies feel like intrinsic values rather than an arrogant pose. Underneath his stoic surface, he lets the mystery of the creative process softly rumble, revealing that perhaps inspiration simply comes from being present and alert to what is going on around you. When the modern world and life’s surprises come to disturb Paterson’s routine, however, Driver gives weight to his sorrow, aligning the audience with his fear that the simple existence he wants may no longer be possible today. An almost childlike anxiety and sense of curiosity permeate his performance as Paterson witnesses the inevitability of change and pain and the ease with which his wife embraces it, as he wonders how he himself can best accept it. —Manuela Lazic

76

Michael Fassbender as Brandon Sullivan, Shame (2011)

Steve McQueen, who previously worked with Michael Fassbender in the also excellent Hunger, has said the actor was his first and only choice to play the sex-addicted protagonist Brandon in Shame. It’s easy to see why. Fassbender, who always excels with complex characters caught in a morally grey area, radiates the simmering intensity required for the role. Exhibit A: a scene on the New York City subway in which Brandon catches the eye of an intrigued woman, who initially appears to reciprocate interest, only to grow uneasy with Fassbender’s unflinching stare. Not a word is spoken between them, but the dynamic is clearly apparent to the viewer, in large part due to the excellent acting. One can only wonder how Fassbender’s Oscar chances would’ve fared in 2011 had Shame not been rated NC-17. Then again, that movie might not have provided a runway for Fassbender’s most haunting moments in the film. —Aric Jenkins

75

Adele Haénel as Héloïse, Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019)

For most of the film, Héloïse doesn’t blaze—she simmers, until the fire finally literally catches her gown. Truthfully, either or both of this film’s leads deserve a spot on this list, but Haénel shoulders a lot as Héloïse—the subtle changes that mark her shift from skeptical to smitten, a feral spark smothered by the suffocating rules of her era. But if you need further justification for Haénel’s inclusion, look no further than Portrait’s final moments, as Héloïse watches an orchestra play the same Vivaldi that Marianne had shown her years earlier. Her face crumples, tears streaming down her face as the camera moves in. She cycles through a world of emotions without ever uttering a word or even looking at the lens. It’s not just a performance; it’s combustion caught on film. —Sayles

74

Melissa McCarthy as Megan Price, Bridesmaids (2011)

When it came time to cast Bridesmaids, Paul Feig couldn’t find the right person to play Megan. This was a problem. She was supposed to be the kind of comedic supporting character the audience latched on to. Luckily, cowriters Kristen Wiig and Annie Mumolo suggested bringing in their friend: Melissa McCarthy. They told Feig that whenever she was scheduled to perform with the Groundlings, people lined up around the block.

At McCarthy’s audition, Feig asked her to improvise a scene in which Megan tries to convince Wiig’s character, Annie, to go to a bar together. “She goes in on this whole thing,” Feig recalled to me in 2021. “Like, ‘We’re going to get out there, we’re going to get these men, and we’re going to tear ’em apart. We’re just going to eat ’em alive and have a man salad.’”

McCarthy thought she’d blown it. Feig thought the opposite. “We looked at each other and went, ‘That’s her.’” And it was. In hindsight, it’s hard to imagine anyone else as Megan, whom McCarthy plays as a little sly, a little filthy, and a little unhinged. The performance is as good as Belushi’s and Farley’s best—and it earned her something those guys never got: an Oscar nomination. —Siegel

73

Jack Black as Dewey Finn, School of Rock (2003)

Dewey Finn is a freeloading loser who steals his roommate’s identity and manipulates a bunch of children. So why is he so stinkin’ adorable? Casting Jack Black certainly has a lot to do with it, particularly when Mike White has catered the role to his every talent and Richard Linklater has curated the perfect environment for him to spend an hour and 50 minutes in a state of near-constant transcendence. It’s a career-defining performance, a Molotov cocktail of his Tenacious D–bred musicality, “scoobily-doo” silliness, and penchant for punching one word just a little bit harder for maximum comedic effect (case in point: “I’ve got a headache, and the runs”). Linklater shoots it all like a guy who knows he’s catching lightning in a bottle, letting the film’s signature sequences play out in long takes which only underscore Black’s high-wire act. But the heart of the anarchy is a genuine dignification of his young scene partners, from the “fancypants” stylist to the chubby girl afraid to get onstage—loving grace notes which give just the right shades of “inspirational teacher” while never forgetting the foremost assignment: “kick some ass.” Get bent, Glenn Holland and your opus. I pledge allegiance to Mr. Schneebly. —Wilson

72

Val Kilmer as Perry van Shrike, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (2005)

Shane Black writes the kind of rat-a-tat dialogue that has to be delivered perfectly or else it’s dead on arrival; every syllable is a matter of life and death. Ostensibly, Val Kilmer’s character in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang isn’t much more than a running juvenile joke: a gay LAPD detective and Hollywood cop show consultant referred to by friends and perps alike as Gay Perry. But his acting radiates with an indignant sort of dignity—Perry’s too much of an asshole to be anybody’s punch line—and the line readings are chef’s kiss, over and over again. “No, she’s just resting her eyes for a minute,” Perry snaps when queried about the status of an obvious corpse. “Of course she’s fucking dead, her neck’s broken.” Or: “I want you to picture a bullet in your head; can you do that for me?” Or: “Go. Sleep badly. Any questions, hesitate to call.” Kilmer was always a killer comedian (he should have won an Oscar for his rubber-limbed Elvis impersonation in Top Secret!, or maybe a Nobel Prize), and the pleasure of seeing him go back and forth with Robert Downey Jr.—the ideal straight man in a platonic B-movie bromance—is mitigated only by the frustration that he wasn’t cast in movies like this more often. —Nayman

71

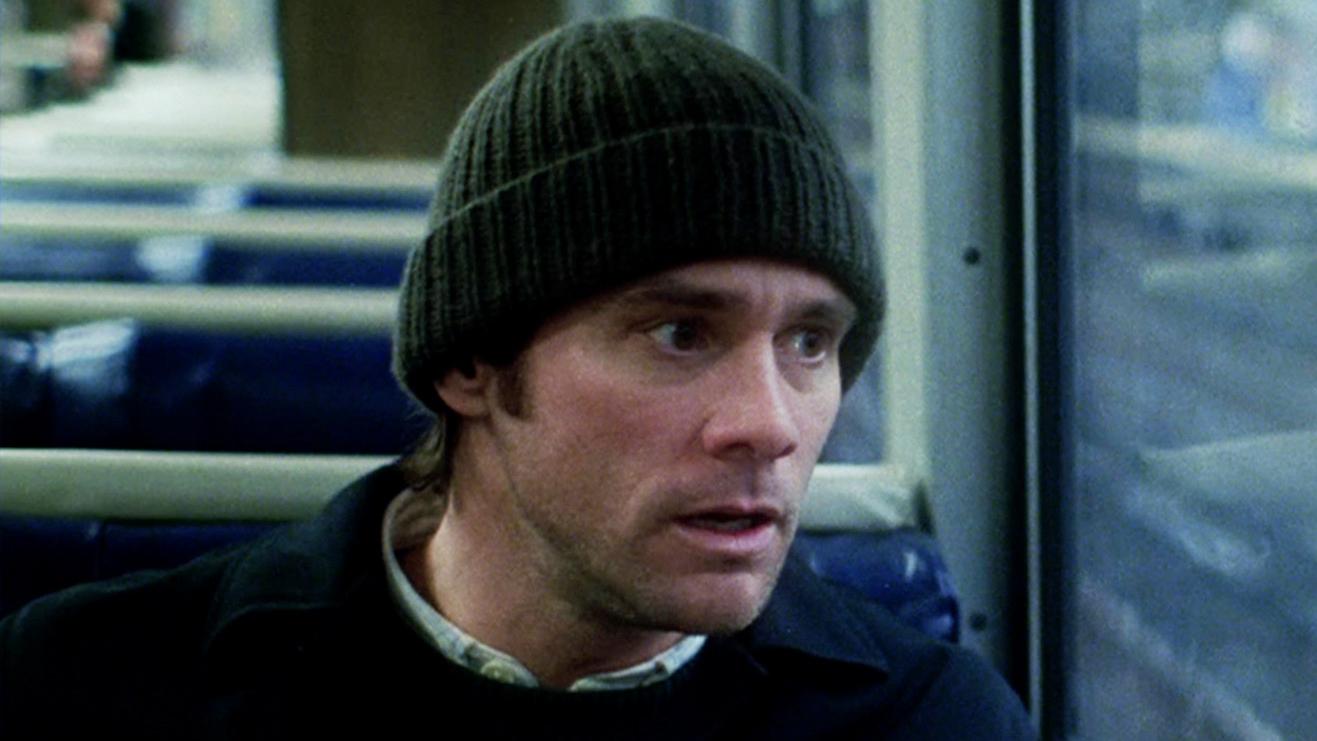

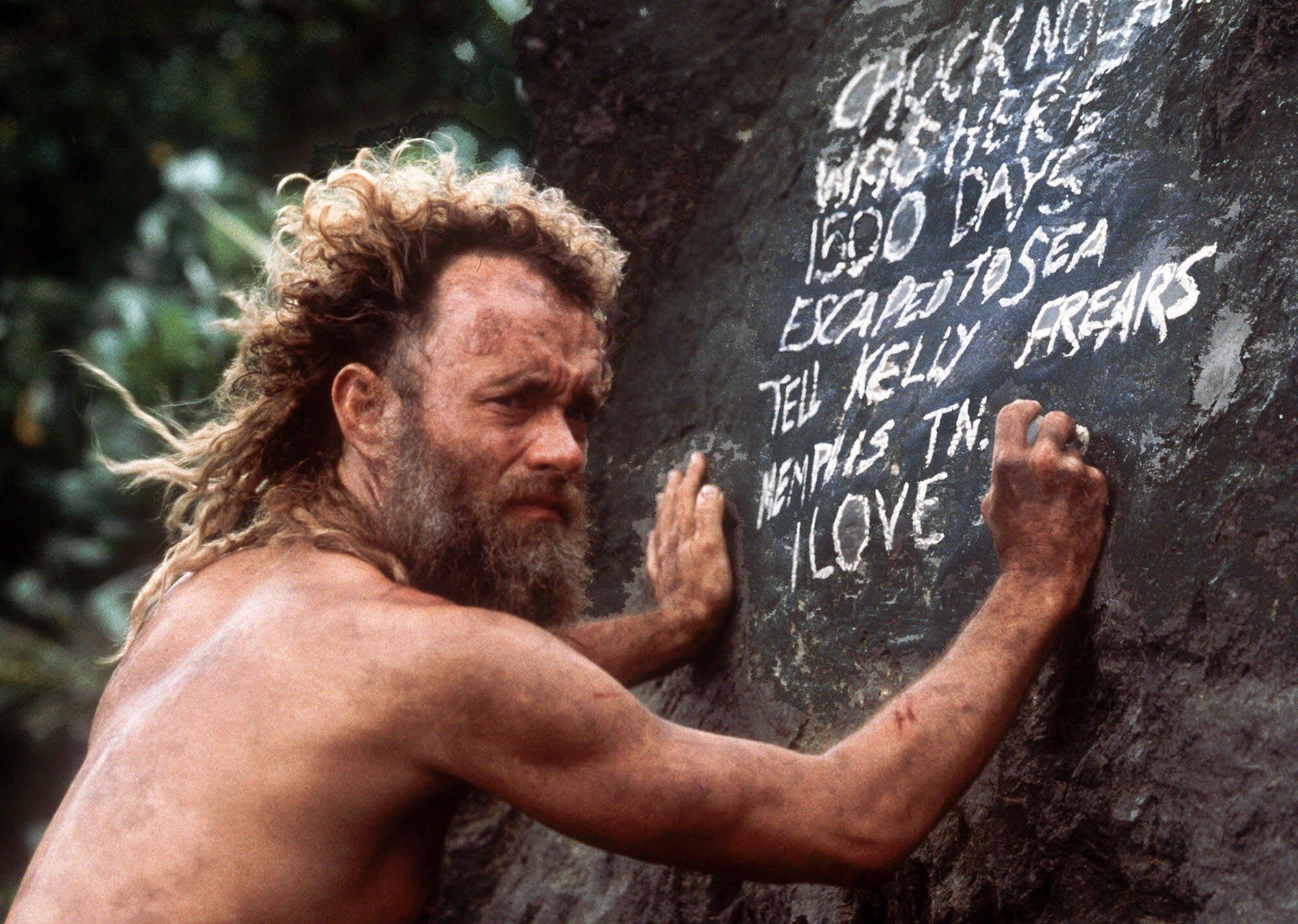

Tom Hanks as Chuck Noland, Cast Away (2000)

Playing a man stranded on a deserted island for four years is, obviously, both mentally and physically challenging. For the role, Tom Hanks lost 50 pounds. After a cut on his leg got infected, he had to be hospitalized. “I was there for three days with something that, believe it or not, almost killed me,” Hanks said in 2009. For a long stretch of filming, his scene partner was a volleyball. Seriously, who else could make Wilson a sympathetic character?

All that stuff is extraordinary.

What’s less obvious but equally impressive about Hanks’s performance is that it’s actually three: Chuck Noland before the plane crash, Chuck Noland as a survivalist, and Chuck Noland post-rescue. During the movie, the character’s appearance and personality gradually evolve. Cast Away isn’t always subtle, but Hanks’s transformation is. —Siegel

70

Robert Pattinson as Connie Nikas, Good Time (2017)

After he played a vampire but before he played the Batman, Robert Pattinson had a different career-boosting role as a brooding creature of the night. As a petit NYC criminal named Constantine "Connie" Nikas in Josh and Benny Safdie’s tense caper Good Time, Pattinson turned in a performance pulsing with resourceful machinations and shameful decisions. A spiritual cross between Christian Slater’s character in Very Bad Things and Ziggy Sobotka, Connie marked a real departure from the soulful Edward of Pattinson’s Twilight fame.

That was by design. It was Pattinson who initially reached out to the Safdies and not the other way around, as the actor wanted to move away from his Twilight fame by disappearing into a new role. The plan worked: Matt Reeves, who directed The Batman, saw Good Time while he was in the process of writing the film and “became dead-set” on casting Pattinson in the titular role based on what he saw from Connie. “He’s got an inner kind of rage that connects with this character and a dangerousness, and I can feel this desperation,” Reeves said, and the rest is history. —Katie Baker

69

James Franco as Alien, Spring Breakers (2012)

It’s not even close to the best performance on this list, but it’s the one I think about the most. While James Franco’s legacy has certainly changed since 2018—when students said that he engaged in sexual misconduct and exploitation at his acting school—it’s still hard to look away from Alien. He’s the most hypnotically ridiculous movie character of the past 25 years, a white drug dealer who has cornrows, a shiny grill, enormous sunglasses, and a bed that’s a fuckin’ art piece. He’s not from this planet, y’all.

Franco plays Alien like Riff Raff, and I’m sorry to say: It works. All of his lines are quotable. I mean: Every. Single. One. I challenge you to watch this monologue, which the actor delivers shirtless while wearing a pair of calf-length Zubaz shorts, only once. Seriously, just look at his shit. —Siegel

68

Ethan Hawke as Rev. Ernst Toller, First Reformed (2017)

Paul Schrader’s best works all seem to circle the same doomed archetype: desperate, principled men (no matter how questionable those principles may be) inhabiting a world they find confusing, who start low and end up going even lower—and who, not coincidentally, end up on something like a suicide mission. There’s a straight line to be drawn between Taxi Driver, Hardcore, Mishima, and what’s easily his best movie of the 21st century, First Reformed. That descriptor is largely a testament to career-best work from Ethan Hawke, who embodies the classic Schrader protagonist better than anyone has since Travis Bickle shaved his hair into a Mohawk. As a struggling pastor named Ernst Toller, Hawke nearly literally loses his religion after finding himself shaken by the death by suicide of a troubled parishoner and ecoterrorist. Quickly, he finds himself seeing the cracks in everything he stands on—the hypocrisy of his church’s biggest benefactors, the rotting world we’re leaving behind for our children, his inability to love or be loved, and his unanswerable, pressing question: “Will God forgive us?” Hawke suppresses all of his boyish charm and cool-dad charisma to deliver something that’s quiet, plaintive, and exhilarating as it builds toward an explosive—figuratively, of course—conclusion. It’s enough to make you take your own Magical Mystery Tour out of your seat. —Sayles

67

Michael B. Jordan as Elijah “Smoke” and Elias “Stack” Moore, Sinners (2025)

From Wallace to Adonis to Killmonger, Michael B. Jordan has proved himself an essential 21st-century performer across television and film. But his most recent (dual) performance as twins Elijah “Smoke” and Elias “Stack” in Ryan Coogler’s Sinners is transcendent and the best solo twin performance since Lindsay Lohan’s star-turn role in 1998’s The Parent Trap. The transformative performance is a match for Coogler’s vision, a truly fresh take on what horror can be: equal parts funny, emotional, campy, and socially and historically significant.

In Sinners, Jordan goes beyond charisma and craft. He excavates something raw, unnerving, and human while carrying the emotional, historical weight of Black men in the Southern United States. Smoke is impulsive, charismatic, filled with rage. Stack is quieter, methodical, and haunted. Jordan gives each character a unique personality and an entire life. His distinct body language, from brow bone to toes, informs the audience which twin they're watching at any given moment. Every shared scene is better than the next: Having himself as a scene partner is a challenge Jordan and this film needed. What makes his role in Sinners a performance of the quarter century isn’t just the technical brilliance—it’s how Jordan finds ground truth in both roles. And, vitally, how he makes spitting hot. —Carrie Wittmer

66

Timothée Chalamet as Elio Perlman, Call Me by Your Name (2017)

Timothée Chalamet’s first great feat was to breathe life into the fuckboy. Not just in Lady Bird, but in Call Me by Your Name, too, where he embodies the swagger and insecurity of the too-smart-for-his-own-good Elio, the knowingness and ignorance and false bravado of a pretty boy caught up in his first love affair and leaving the collateral damage of adolescence behind him, peach by peach. Even the spurned Marzia can’t blame him for his wrongs; maybe it’s because of all those longing stares, which speak to a soul-meets-body intensity that the rest of us wish our own personal fuckboys could feel, even if it’s not for us.

And yes, that yearning-by-the-fireplace scene has a life of its own now in the meme cycle. Sometimes, we mock the things that move us most, fearing the cringe instead of feeling the pain. But just admit it: When you watched that scene for the first time, feel something you obviously did—and it really is OK to feel the love for Timmy, instead of making yourself feel nothing, so as not to feel anything. —Hunt

65

Björk as Selma Ježková, Dancer in the Dark (2000)

It’s sometimes easy to forget that it’s Björk at the center of Dancer in the Dark, until she starts singing.

Björk—in her first major film role—was really playing two characters in Dancer in the Dark: a classic Lars von Trier heroine who’s beaten down by parodic levels of tragedy, and a fantasy of the factory worker Selma, whose brightness could have come only from the singer. As Björk herself says, for most of the movie, she disappeared into the role, sinking so deep into her character that the singer herself slips out of view. The alchemy of the performance was likely in spite of Björk’s reported clashes with von Trier, ranging from disagreements over the music and dour tone of the movie to Björk’s reports of sexual harassment by the director. I think it would be wrongheaded to credit her acting to the abuse she says von Trier committed; the places she goes in the movie are hers alone to access, and it’s clear from what Björk’s said about Dancer in the Dark that she had a clear vision of her character that she wasn’t willing to give up for the director’s sake—a tribute to the similarly uncompromising Selma. Björk may never take on another role like Selma (whether because of her experiences on Dancer in the Dark or just because she prefers to make music), but her performance is proof of the magic she’s capable of even when she isn’t singing. —Hunt

64

Laurie Metcalf as Marion McPherson, Lady Bird (2017)

One of our finest living actors and a force of nature. She very much has the range. Metcalf is perfect in Lady Bird. Everyone talks about the airport scene at the end, and so will I, but her shining moment may be Christmas morning as the McPherson household sat around the tree. She apologizes that it’s a small Christmas this year, then watches her family open their presents. Her kids all get socks. Her husband, a luminous Tracy Letts, gets a decorative pillow. On the front: GOLFERS NEVER DIET, THEY JUST EXIST ON GREENS. Metcalf is hooting, hollering, giggling, shaking her head. “It just makes me laugh,” she says. Some actors can’t laugh on-screen and make it look authentic. They try and come off looking like they’ve never laughed a day in their lives. Metcalf knows her way around a laugh, and when she lets one go, the screen glitters.

And then there’s the car ride. It’s not the last scene in the movie, but it’s close. Metcalf and Letts drop Saoirse Ronan at the airport so she can fly to New York to attend college, a decision Metcalf is devastated by. She refuses to get out of the car while Letts takes Ronan inside. And Metcalf is cold and mad when she pulls out of the departure drop-off. The camera stays in the car with her as she circles the airport. We watch her wall come down and her face transform. We watch her work through her heart. We watch her regret. We watch her try to get back in time to hug her daughter. We watch her think and cry and panic and fail. —Parker

63

Saoirse Ronan as Lady Bird McPherson, Lady Bird (2017)

By the time Saoirse Ronan played Lady Bird (it’s the titular role!), she’d already been nominated for an Oscar twice. She was 23 years old. It is the mark of one of our finest young performers to be able to pull off the itchy self-righteousness of a teenager sure she’s ready to take on the whole world without immediately alienating the audience—basically, to convincingly play annoying with all the empathy, complexity, and power that annoying teenagers deserve to be met with but rarely are. If only all of our adolescent selves could have been played by Ronan when struck with a raging case of senioritis! Before Lady Bird, Ronan was mostly known for playing dramatic (and again, often Oscar-nominated) roles. To suddenly see her playing a Sacramento teen, performed with all the comedic wit and tear-jerking whimsy of Greta Gerwig’s pen, felt like discovering her all over again. —Walker

62

John C. Reilly as Dewey Cox, Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story (2007)

A performance so good that it turned a genre into a punch line. All the trope-heavy music biopics since, even the ones that won Academy Awards, have been compared to Walk Hard. That’s because of John C. Reilly. The movie was a parody, but his work was no joke. He sang and strummed dozens of songs himself. He didn’t lip-synch or rely on a stand-in. He didn’t just play genre-spanning artist Dewey Cox; he became him.

There were times, like the day on set when the star assumed a Bob Dylan–like persona, when it all felt real. “I remember standing up there rehearsing it and dressed like Dylan and feeling like, ‘Oh my God, I feel like Bob Dylan!’” Reilly told me for a Walk Hard oral history back in 2019. “It’s insane.”

Thanks to Reilly, Walk Hard is a fake music biopic that’s better than most real music biopics. Not that it stopped other filmmakers from walking hard themselves. “Oh, we tried to kill the musical biopic with this movie,” Reilly said. “And it turns out it’s a very resilient cliché.” —Siegel

61

Anne Hathaway as Kym Buchman, Rachel Getting Married (2008)

In 2008, the nonsensical backlash to Anne Hathaway was in full swing. Supposedly, she was unlikable because she “tried too hard”—whatever that means. It’s too bad for them because at just 25 years old, Hathaway was out there turning in a performance that most actors would take a lifetime to nail. In Jonathan Demme’s perennially undersung classic of familial tension, Hathaway’s Kym returns home from an umpteenth stint in rehab for her sister’s wedding, ready to raise hell. Addiction is so hard to get right, and most actors go big and play it to the rafters. Hathaway has moments of delusional grandeur here, sure, but the way she rides the tonal wave of what it’s like to know an addict is astonishing. One minute they’re promising you the world, reflections of the person you knew before this sickness flickering through. The next, they’re bellowing at you, full of rage. Hathaway finds that imbalance with shocking urgency, the film mirroring her inconsistencies and throwing you around with reckless abandon. All of the physical prerequisites are there: the bloodshot eyes, the sunken face. But it’s Hathaway’s internalization of what it means to live with this illness that shines through: a hurt, broken child begging just one person to do right by them. Anybody can play unlikable. The devastating reality of somebody like Kym is that you don’t dislike them. They’re too damn magnetic, which is why they’ve been able to get away with it for so long. Hathaway plays that with jarring accuracy and, in the process, proves that she was never unlikable. You just couldn’t handle authenticity. —Brandon Streussnig

60

Rooney Mara as Lisbeth Salander, The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo (2011)

Given the unenviable task of re-creating instantly iconic character Lisbeth Salander for David Fincher’s American remake, Rooney Mara didn’t just put her own spin on it—she made the character inextricable from herself. An impossible mixture of feral, blunt, and delicate, Mara’s gait is what stands out the most. Somehow slinking into scenes but taking up the entire frame, her Lisbeth is a poison pill to a society that valorizes sadistic men. Shaved eyebrows, pierced nipples, rocking a “Fuck You, You Fucking Fuck” tee underneath a leather jacket, Salander should be a walking cliché. A hardened antihero with little interiority. In Mara’s hands, she exists within a complexity where she suffers horrific abuse and plays it with the traumatized pathos it deserves, but it never defines her. She isn’t an avenging angel without emotion but a woman who craves sensuality, love, and to be desired. Living within those polarities, the push and pull of wanting to be seen when your instinct is to disappear, Mara is unforgettable. We can’t predict how we’ll respond to traumatic experiences. Through Mara, Lisbeth Salander transcends pulpy paperback heroine and becomes an honest representation of what it means to survive pain. —Streussnig

59

Michelle Williams as Cindy Heller Pereira, Blue Valentine (2010)

There are unfathomable levels of 2010 happening in this movie. (Ryan Gosling playing a ukulele? Handheld shots on the Manhattan Bridge? Closing credits set to Grizzly Bear?) But what could easily be written off as elder-millennial misery porn is transformed into something more resonant thanks to Michelle Williams, who plays a working-class mom having to deal with two children—her young daughter and her adult husband. The smash cuts across two timelines only accentuate what she’s able to do in the role, shrinking from a wide-eyed firecracker to someone who's been beaten down by years of living with a partner who can’t grow alongside her. Your mileage may vary on the whimsical tap dancing—again, it was the Great Recession—but you’d be hard-pressed to find a more grounding performance in a film that needs one. —Sayles

58

Choi Min-sik as Oh Dae-su, Oldboy (2003)

Give Choi Min-sik this: He’s the only actor on this list who consumed four live octopuses to get here. As the title character of Park Chan-wook’s hallucinatory psychological thriller Oldboy (real name: Oh Dae-su), Choi swallows his pride along with those cephalopods—he’s drugged, imprisoned, framed for murder, beaten, tortured, and thoroughly mind-fucked. He’s the oblivious and increasingly enraged victim of a conspiracy that, in the best paranoid tradition, winds backward into his own unsavory past. He also gets to dish out his share of punishment, though: The film’s side-scrolling, single-take, 40-against-one hallway fight is one of the great contemporary action set pieces, and Choi, who did his own stunts, shot about 15 takes to get it right. The madness of his method paid off—Oh Dae-su is an indelible antihero who goes through the wringer and gets the happy ending (or is it?) that he deserves. —Nayman

57

Emma Stone as Mia Dolan, La La Land (2016)

I think a lot about Young Jeezy. Over the past 20 years, the Atlanta native has become a supremely competent rapper, the kind who can be plugged onto pop singles and work in a syntax that’s comfortable for radio listeners and mainstream fans. But he’s never been able to recapture the magic of his 2005 debut album, Let’s Get It: Thug Motivation 101, where his technical incompetency—a series of one- or two-bar punch ins, rhyme schemes, and cadences that could be described as elementary—served only to underscore the clarity with which he saw the world and his hunger to bend it to his will. When La La Land was announced, the news that Emma Stone and Ryan Gosling would be doing their own dancing and singing was met with incredulity: Why? But the timidity with which Stone approaches those sequences as Mia, an aspiring actress, is a perfect distillation of the precarity and self-doubt with which the industry and city can suffuse the people who make them run. —Thompson

56

Julianne Moore as Cathy Whitaker, Far From Heaven (2002)

Todd Haynes’s greatest muse doubles as the engine for one of his boldest creative swings: a Douglas Sirk–style melodrama that also aims to capture modern themes. As Cathy Whitaker, Julianne Moore nails the tone and mannerisms of a ’50s housewife with pinpoint precision, but she’s also masterful in her reactions to the discovery that her husband is gay (the post-solicitation police station scene alone should’ve won her an Oscar) and in moments when she seeks refuge in her growing romance with her Black landscaper. It’s a character who’s long used to burying their emotions letting them bubble to the surface, and as upper-middle-class anxieties go, the movie’s nearly on par with the ’90s Haynes-Moore classic Safe. Thirty years on, and just a few after the master class of May December, the actor and director have cemented themselves as a pairing on par with Scorsese and De Niro or Spike and Denzel—and perhaps one capable of dreaming bigger. —Sayles

55

Michelle Yeoh as Yu Shu Lien, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000)

The most celebrated actors of the 21st century are often the best at selling exertion. There’s a reason the Oscar race tends to reward extremity (e.g., Leonardo DiCaprio in The Revenant or Brendan Fraser in The Whale). Performance as an Olympic feat is easy to hawk on- and off-screen.

In contrast, Michelle Yeoh is a devastating ball of restraint and control in 2000’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. The poetry of Yeoh’s movements relies on her ability to erase the effort. Her martial arts are akin to breathing. Shu Lien’s entire existence—from her tragic love story with Mu Bai to the generational war with Jen—can be mapped by the sheer grandeur of each set piece, but it never points to the absurdity of its difficulty.

Yeoh is a subtle actor, her face just as much of a honed muscle as the rest of her body. The most devastating moment in Crouching Tiger arrives as Shu Lien listens to Mu Bai confess his feelings before dying. As the camera holds on Yeoh’s face, her watering eyes demonstrate a decade of lost time and regret even as Shu Lien’s mask holds strong. It’s as if every fiber in her cheekbones is resolved not to scrunch into despair. When Yeoh’s pained and tearful kiss finally finds her lover’s lips, the kick lands harder than any other blow in the entire movie. —Charles Holmes

54

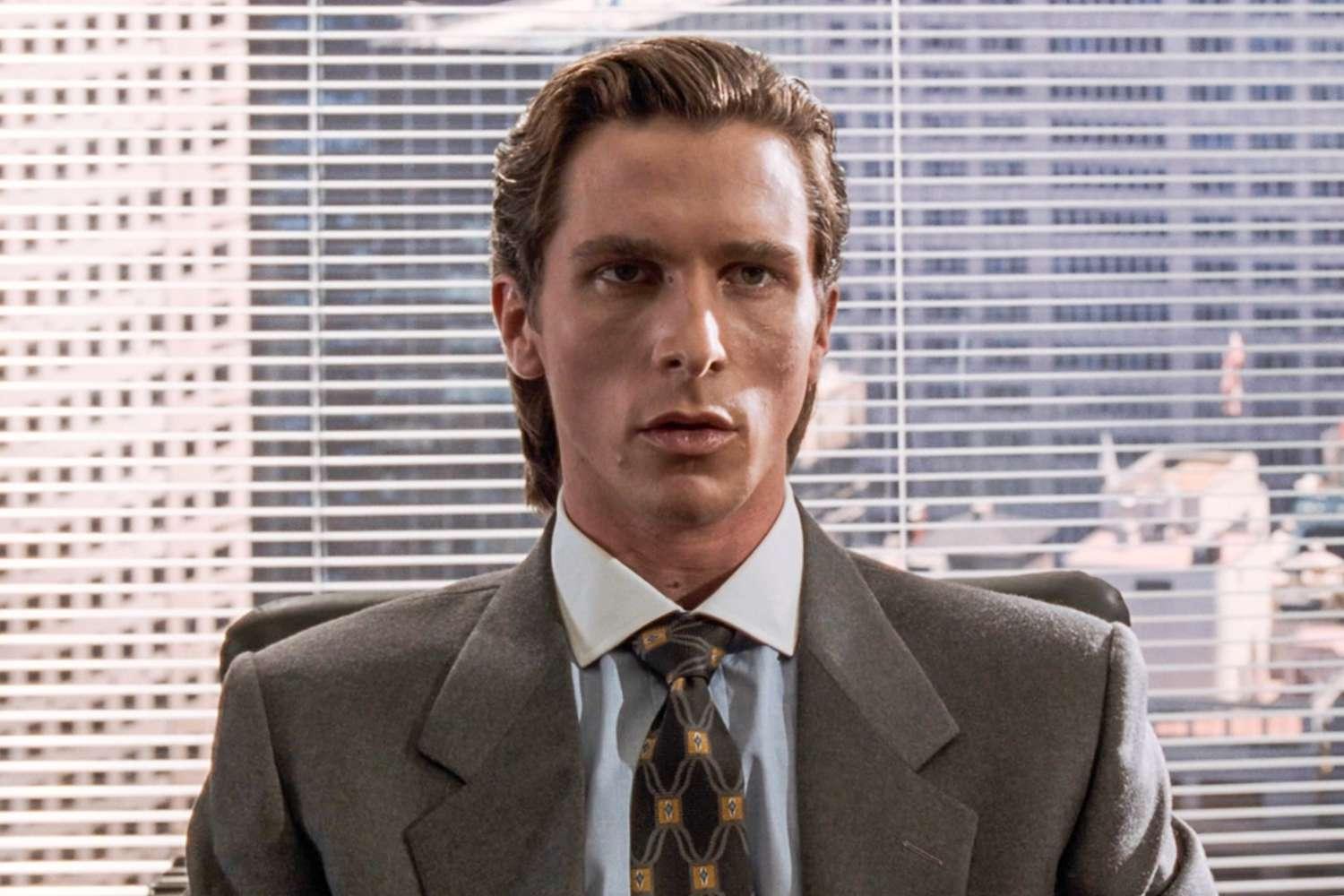

Christian Bale as Patrick Bateman, American Psycho (2000)

The first time I saw American Psycho, it confused me—a 13-year-old who wasn’t exactly sure if everything I’d just watched was legitimately scary, merely disturbing, or simply artificial. The last time I saw American Psycho, I wondered whether Christian Bale was, in fact, the funniest person alive. It’s easy to bungle a satire, but few things are more satisfying than a razor-sharp depiction that slices through every nook and cranny of its target. That’s exactly what Bale does.

It's 1987, and Bale's Patrick Bateman is a soulless financier with psychotically violent fantasies. Just about everything about him is hysterical, from the devotion to a well-considered and insane glam routine (that’s ironically back in style) to being transfixed by “The Lady in Red” while he’s supposed to be working, to dropping a chainsaw down a staircase with the concentration of a jeweler peering through their loupe. Bale is more than committed to creating a douchebag for the ages. Needless to say, he succeeds. —Pina

53

Penélope Cruz as Raimunda, Volver (2006)

For a film that deals with dark subject matter such as death, grief, and sexual abuse, Pedro Almodóvar’s Volver is still uplifting and unexpectedly funny. The 2006 film balances its high drama and its comedy with a natural ease, carrying the weight of its solemnity without its playful humor ever undercutting its sense of purpose. That speaks to the masterful filmmaking of Almodóvar, who wrote and directed the movie—but it’s also a product of Penélope Cruz’s dazzling performance at its center.

Cruz stars as Raimunda, a mother living with her daughter in the suburbs of Madrid whose tragedies are varied and ever growing. Starting with a self-defense killing in the family, Volver is full of unexpected twists and turns, and Cruz is the perfect guide to lead the audience on its startling cinematic journey. Raimunda is witty, razor-sharp, and kind—yet she carries a deep sadness that surfaces in her rare moments of unguarded vulnerability. She uses her charm against her friends, family, and neighbors in a way that feels less manipulative than it does resourceful. And Cruz plays the part with a confidence that makes Raimunda seem real and lived in, with relationships that are so believably authentic and full of history.

Cruz’s performance in Volver earned her a nomination for Best Actress at the Academy Awards in 2007; she was the first Spanish woman to ever receive a nomination in the category. She may have been denied the ultimate honor that year, but she would later make history again when she became the first—and, to this day, only—Spanish actress to win an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress for her performance in 2009’s Vicky Cristina Barcelona. —Daniel Chin

52

Ralph Fiennes as Monsieur Gustave H., The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

It’s almost miraculous that Wes Anderson films have been home to so many great performances. Anderson exerts total control over every inch of every frame and over every line of dialogue, an approach that seemingly ought to stifle his cast’s ability to make characters their own. Yet, in film after film, actors not only deliver some of their best work but also showcase aspects of their craft unseen in others’ movies. Fiennes was no stranger to comedy before The Grand Budapest Hotel, but nothing in his previous work suggested that he could play a character like Gustave H., the concierge at the luxurious eponymous hotel who, in the most winning and unapologetic way possible, philanders his way through his employer’s aging, wealthy clientele. (“I go to bed with all my friends,” he nonchalantly explains.) The embodiment of an old world about to be swept away by the tides of history, Fiennes conveys the character’s charm and innate innocence, giving a human face to what’s lost when one era ends and another, crueler one begins. —Keith Phipps

51

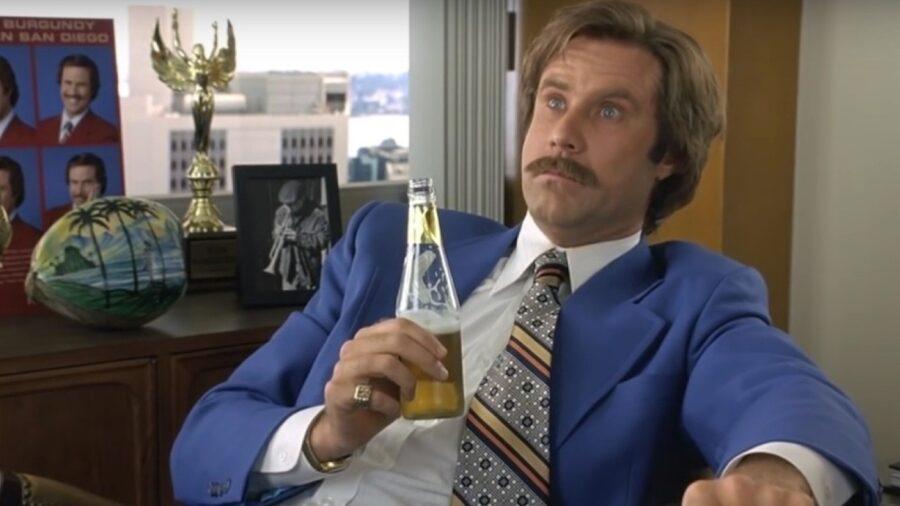

Will Ferrell as Ron Burgundy, Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy (2004)

Hear me out: There’s a 2019 podcast clip of comedians Kristen Schaal and Anthony Jeselnik arguing, politely, about whether comedy depends 100 percent on surprise. Jeselnik says yes: A punch line is a surprise that makes you laugh, period. But Schaal argues that sometimes comedy is about commitment: A punch line can be a slow, escalating, unwavering, inevitably uncomfortable refusal to abandon the bit. Chris Farley auditioning for the Chippendales on SNL is her example of total commitment as punch line; Will Ferrell in Anchorman is mine.

You can rhapsodize about his performance as clueless, tactless, ultra-entitled, super-macho, George W. Bush–era incarnate doofus Ron Burgundy entirely via one-liners and memes: “Well, that escalated quickly.” “Go fuck yourself, San Diego.” “I’m in a glass case of emotions.” But what makes this character undeniable is the 60 seconds Ferrell spends beforehand in that glass case of emotions, wailing uncontrollably. It’s excessive, it’s unpleasant, it’s extraordinary, and it’s a phone booth, but you knew that. Everybody does. Anchorman is eternal because every second this guy’s on-screen, you think, He can’t keep this up, but he never stops, whether he’s brawling with Christina Applegate, or crooning “Afternoon Delight,” or (personal favorite) sliding under the bathroom stall while playing the jazz flute. “That escalated quickly” makes this movie eternally quotable; Will Ferrell’s heroic and unstoppable escalation makes it eternally great. —Harvilla

50

Russell Crowe as Maximus Decimus Meridius, Gladiator (2000)

Russell Crowe got Gladiator because Mel Gibson said no. That was lucky for Crowe, and fortunate for fans of swords and sandals, because nobody could’ve been a better Maximus Decimus Meridius than the literal Best Actor. Crowe has been involved in numerous off-screen altercations, but the on-screen fights in Gladiator left his body banged up; he suffered for his art. The filmmakers may have suffered some, too, when Crowe balked at speaking some of the dialogue in the amorphous script, but he also suggested or improvised certain scenes and lines that made the story stronger. And regardless of who wrote Gladiator’s most memorable material, Crowe’s deliveries cemented the movie’s reputation for being incredibly quotable.

Crowe’s physicality and quiet intensity gave Gladiator a gravitas it otherwise might have lacked; the movie made him a major star, and he made the movie a Best Picture winner. On paper, the logline for the second-highest-grossing release of 2000 might have sounded like a formula for a forgettable, pulpy popcorn flick, but when Maximus asked, “Are you not entertained?” Crowe could anticipate his audience’s answer. —Ben Lindbergh

49

Forest Whitaker as Idi Amin, The Last King of Scotland (2006)

It’s the most terrifying performance I’ve ever seen. It’s terrifying because it’s so unpredictable. Forest Whitaker’s Idi Amin swings from dead-eyed contempt to sudden hilarity, from knife’s-edge paranoia to easygoing charm, from charismatic idealism to brutal violence, often when you least expect it. Many actors have played volatile characters, but true unpredictability is hard to achieve in a medium where all the material is scripted in advance. You can try, as an actor, to stay in the moment, but what you do on the second page of a script will almost inevitably be informed by what you know is coming in the third. The greatness of Whitaker’s performance in The Last King of Scotland is that he makes you believe that the next page hasn’t been written yet. He could truly go in any direction at any moment, and because he’s playing a murderous dictator, the uncertainty is both utterly compelling and intensely frightening. Last King is (sorry) a problematic movie in many ways, and it’s a strange movie in almost every way, but Whitaker’s Amin expands our understanding of power itself. I’m more afraid of him than of Hannibal Lecter. —Brian Phillips

48

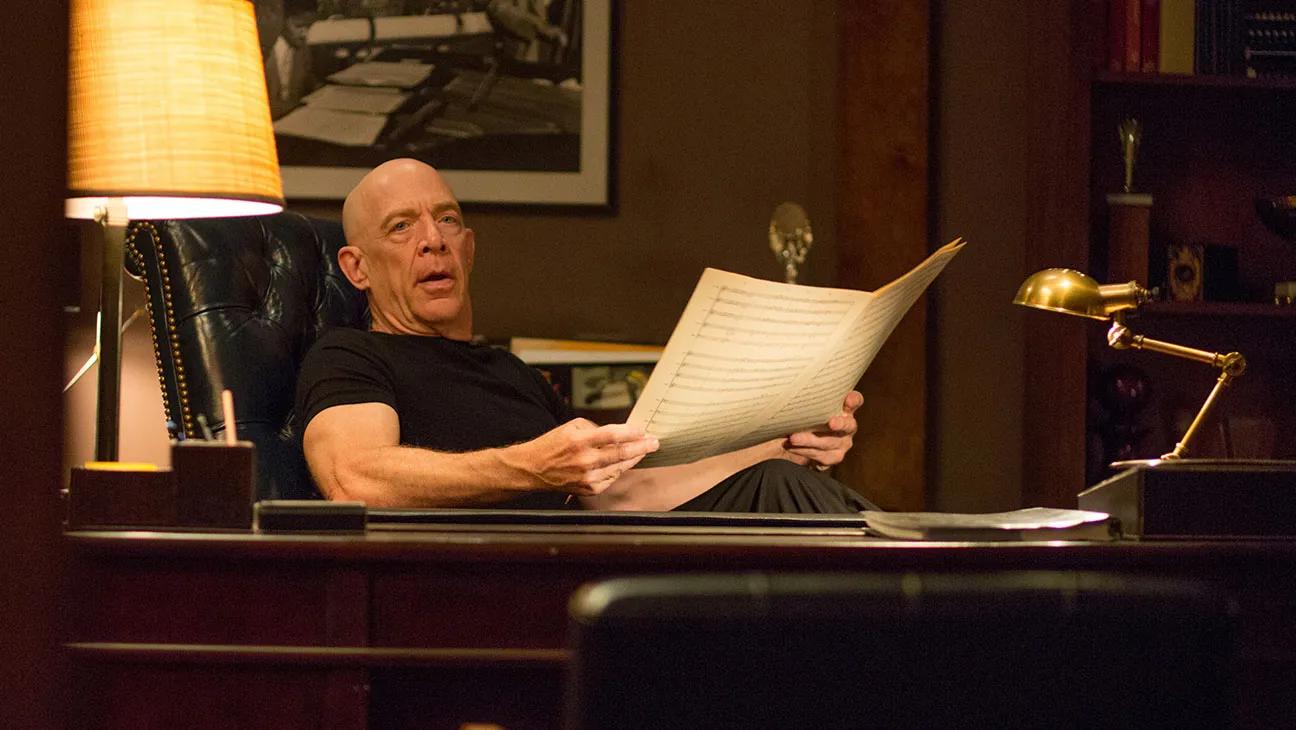

J.K. Simmons as Terence Fletcher, Whiplash (2014)

J.K. Simmons was a great J. Jonah Jameson, but it’s his performance in Whiplash that he’ll likely be most fondly remembered for—which is a bit of an odd thing to say about a tyrannical, abusive master manipulator. The psychological torture inflicted by Simmons’s Terence Fletcher isn’t just a collection of screaming temper tantrums—it’s the subtle gaslighting, the backhanded compliments, and the true conviction in his demanding methods that make the character so complex and, at times, dare we say, strangely endearing. This is a man in pursuit of pure excellence, and the competence on display can almost pull you on his side, even if his occasional charisma too often gives way to dehumanizing ruthlessness. Suffice it to say, this was a fine line for any actor to walk, but Simmons managed to nail the tempo and win a hugely deserved Academy Award. —Jenkins

47

Olivia Colman as Queen Anne, The Favourite (2018)

By the time Yorgos Lanthimos’s absurdist black comedy take on the British crown premiered in 2018, Olivia Colman was already a beloved actress in the U.K. But it was The Favourite that vaulted Colman to international—and Academy Award—recognition, and deservedly so. Her turn as Queen Anne, the at-once aloof, eccentric, and deeply tragic 18th-century ruler of Great Britain, brims with equal parts pathos and humor. In just a minute-long scene, we witness the delight on Colman’s face as she introduces Abigail Hill (Emma Stone) to her 17 rabbits and then wilts into despair as she explains how the pets symbolize her children, who were either miscarried or died in infancy. At other times, Colman’s expression sours into seething jealousy, like when Sarah Churchill (Rachel Weisz), the Queen’s confidante and secret lover, shares a dance with a member of the royal court. It’s fitting that in a movie in which Abigail and Lady Sarah vie for the affection of Queen Anne, Colman—with all due respect to the superb displays from Stone and Weisz—emerges as the star. Watching her performance truly feels like a prize worth winning. —Jenkins

46

Delroy Lindo as Paul, Da 5 Bloods (2020)

Swirling with contradiction, Delroy Lindo’s Paul is Spike Lee’s most tragic character. A MAGA hat–wearing, viscerally angry Vietnam vet, Paul is the piece of Da 5 Bloods with the most bite. The late, great Chadwick Boseman’s Stormin’ Norman hangs over the film like a specter, but it’s Lindo’s Paul who lands its lasting punch. Paul is the most succinct encapsulation of a man sent to die for his country, only to be spat on—both as a perceived war criminal and because of his skin color—upon returning home. Seething with rage that bubbles above the surface, Lindo accesses a fractured sadness that goes beyond PTSD. He’s not simply traumatized by what he saw. He’s traumatized that his country didn’t give a shit. Overseas or back home, his fight for his basic humanity to be recognized is worn down until his only resolve is embracing a megalomaniacal outsider promising to “drain the swamp.” As he stumbles through the jungle upon returning to Vietnam, the country that began the breaking of his brain, it’s Lindo’s primal whisper of a monologue that sticks to the ribs. As the entire meaning of his life comes into stark relief, his eyes blazing directly toward the camera, he growls, “You couldn’t kill me after three tours, and you sure as fuck can’t kill me now.” As profoundly moving as it is unmooring, it’s the kind of performance that will live on beyond its embarrassing lack of awards attention. —Streussnig

45

Sandra Hüller as Ines Conradi, Toni Erdmann (2016)

“I believe the children are our future,” warbles Whitney Shuck—actually one Ines Conradi, performing at a private function under a stage name whose inception is too complicated to explain here—during the intro to “Greatest Love of All.” Whitney S is no Whitney Houston, of course, but her performance—full-throated, hands waving, and occasionally on key—is captivating all the same. Despite being surrounded by a bunch of Bulgarian Orthodox colleagues, she sings like nobody’s watching. Or more specifically, she’s singing for her father, Winfried (a.k.a. Toni Erdmann), who’s accompanying her on piano just like he did when she was a kid. Written and directed by German genius Maren Ade, Toni Erdmann reimagines familiar daddy-daughter dynamics as a game of chicken; its characters live to egg each other on. The greatness of Sandra Hüller’s performance lies in its mix of steely resolve and helpless submission to her own impulses; no matter how hard Ines tries, she can’t repress the kamikaze exhibitionism that is her birthright. The final sequences of Toni Erdmann push past expertly calibrated cringe comedy to something sublime. When Ines embraces her dad in the aftermath of his most jaw-dropping public stunt, it’s as if she implodes into love and understanding; Hüller’s fearless, emotionally translucent acting shows us that she’s hanging on for dear life. —Nayman

44

Charlize Theron as Imperator Furiosa, Mad Max: Fury Road (2015)

From the moment we first glimpse Imperator Furiosa’s grease-paint-smeared, shaved head peering from behind the wheel of the hulking War Rig, her engine is revving; today is the day she makes a break for it. For the next two hours, she’s aswirl in the tempest of a film equal parts Ben-Hur and Looney Tunes, yet Charlize Theron somehow grounds every glance and gesture with an oil-black well of subtext and feeling. For a film in nonstop motion, she’s a simmering ballast: a woman stripped of humanity, trying to get back home. Simple and spare, yet brimming with contradictions, she plays Furiosa’s gambit of running off with Immortan Joe’s brides as both vengeful abduction and merciful rescue, never settling for mere iconography even as she preserves in blood and chrome one of the great action performances of all time. Her anguished wail at the discovery of her lost Promised Land is one of the defining images of the century, the kind of wordless evocation of character that made it tough for any actress to fill her shoes in the 2024 prequel. George Miller said it best: “You can dress up as Furiosa, but to be Furiosa, you’ve got to be Charlize.” —Wilson

43

Casey Affleck as Lee Chandler, Manchester by the Sea (2016)

As Kenneth Lonergan’s third film opens, Lee, the quiet protagonist played by Affleck, has seemingly found a place in the world in which he feels comfortable, even if no one would mistake that feeling for happiness. A janitor living alone in suburban Boston, he lives a life of solitude interrupted by occasional eruptions of rage. But at least it’s more bearable than life in Manchester-by-the-Sea, home to his family and the site of an unspeakable tragedy. When the death of Lee’s brother, Joe (Kyle Chandler), forces him to return to care for his nephew, Patrick (Lucas Hedges), Lee’s forced out of his angry rut and compelled to confront the past. The brilliance of Affleck’s work here comes from his ability to suggest emotions lurking just beneath the surface—his grief at the loss that’s defined his life, his love for Patrick, his fear that he’ll fuck up his new responsibilities. And he plays them fully when they do surface, whether via fistfights or a reunion with his ex-wife, Randi (Michelle Williams), in which he’s forced to say out loud the feelings he’s done his best to keep even from himself. It’s extraordinary work made all the more remarkable by Affleck’s ability to balance mournfulness with humor and faint, distant notes of optimism that Lee might someday find his way back to the world. —Phipps

42

Andy Serkis as Gollum, The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002)

The Two Towers came out three years after The Phantom Menace, as good an illustration as any of the risks of incorporating a prominent computer-generated character into a live-action blockbuster. Gollum was a make-or-break character in the follow-up to Fellowship: had he come off as cartoonish or fallen into the uncanny valley, he could’ve been a distraction from the drama, majesty, and emotion elsewhere on the screen, creating a debacle like the Gollum video game. Instead, the twisted, treacherous, self-loathing hobbit helped make the movie, thanks in large part to the award-worthy man in the mocap suit: Andy Serkis.

Gollum was originally intended to be 100 percent CGI, but Serkis played him better than a computer could have on its own. (Plus, Serkis’s scenemates acted more effectively when he was on set.) A good deal of the credit for the character’s resonance still goes to Weta Digital’s animators, but Serkis provided the voice, movements, and reference facial expressions that truly brought the hobbit to life—and he didn’t need movie magic to transform into him (or, for that matter, other characters who were almost as memorable). Playing Gollum alone would’ve been tough enough; mixing in Sméagol—the innocent, sunny side of the wretched ring fiend’s split personality—made the performance a master class. —Lindbergh

41

Brad Pitt as Billy Beane, Moneyball (2011)