For a certain type of movie fan, July 17 was a stampede—a free-for-all waged on the opaque battlefield of online ticket queues. Two days earlier, word had spread online that tickets for Christopher Nolan’s The Odyssey would be going on sale a full year in advance of its July 17, 2026, release date. Far from regular screenings, these would be in IMAX 70 mm, an analog format championed by Nolan that only 30 theaters in the world are equipped for. As they awaited the drop, IMAX superfans sharpened their swords, hyping each other up with memes in Discord chats and bidding one another good luck. The carnage commenced around midnight Eastern Standard Time, when the tickets dropped and Discord users with display names such as Weaponized Autism and Matt (Imp the Dimp) leapt into action, elbowing past their brethren to scoop up what seats they could. While the tickets likely didn’t all go to Discord users, within an hour, 95 percent of them were gone. Those who emerged victorious did so at great cost. A Discord user named Dub, who loudly obsesses over seat L21 at the Lincoln Square IMAX in New York City because of how centered it is—allowing his “eyes to capture everything,” he says—secured tickets to several showings, but in other, inferior seats. Those who were defeated threw their hands up and grumbled about the whole thing being a marketing stunt. It’s worth noting that, at that point, The Odyssey hadn’t even finished filming yet.

For anyone who has tried and failed to secure a ticket to an IMAX screening recently—particularly at one of the company’s top-of-the-line theaters like the AMC Lincoln Square 13 or London’s BFI IMAX—it will come as no surprise that there’s a rabid subculture of IMAX superfans. These are the fans who instantly sold out last year’s 10th-anniversary IMAX rerelease of Interstellar (with 70 mm tickets going particularly fast) and who spend their time on Discord servers discussing how many minutes of Sinners’ running time employ IMAX’s traditional 1.43:1 aspect ratio. (This is when the top and bottom of the frame expand during the movie—typically during action set pieces—to fill the entire screen.) Their gods are the blockbuster auteurs who optimize their films for IMAX, including James Cameron, Jordan Peele, and especially Nolan, whom one IMAX superfan I spoke with referred to as “the Chosen One.” Their religious fervor about how Nolan films need to be seen in the format has even spilled over to more casual moviegoers. In 2023, Oppenheimer raked in 20 percent of its nearly billion-dollar haul in IMAX, which operates just 1 percent of movie screens globally. Of course, the true superfans took the extra step of seeing the three-hour epic at one of the 30 theaters equipped for IMAX 70 mm, often traveling hours to do so—in many cases more than once.

Fifty-eight years after IMAX’s humble beginnings in Montreal, studios and box office analysts alike are positioning it as a savior of theatrical moviegoing—a means of eventizing a trip to the movies in the age of streamers. Last quarter, IMAX reported earnings up 41 percent from the same period last year thanks to films that leaned into its technology and sense of scale, including F1, Mission: Impossible—The Final Reckoning, and Sinners, which overperformed in IMAX 70 mm to such a degree that Warner Bros. quickly rereleased it in the format after its initial window. IMAX projects the company will rake in $1.2 billion in the global box office by year’s end, with Odyssey mania already promising a lucrative 2026. Everyone suddenly wants a piece of IMAX—even Paul Thomas Anderson, whose new film, One Battle After Another, comes out this weekend and is his first to be released in the format. While the film was shot on VistaVision (a large format popular in the 1950s that was recently revived for 2024’s The Brutalist), the IMAX release helps Warner Bros. sell it to audiences as a big movie that needs to be seen in theaters. (IMAX screens accounted for 70 percent of presale tickets for the movie at major theater chains, according to an IMAX spokesperson.) But the IMAX release isn’t just a sales tactic. “There were many times on set when Paul would be like, ‘Boy, this is going to look great on an IMAX screen,’” says Michael Bauman, the film’s cinematographer. One Battle’s unconventional production pipeline—being shot on archaic VistaVision film cameras and then meticulously reformatted for IMAX, both digital and 70 mm—speaks to IMAX’s unique role as an end-to-end service that helps filmmakers achieve their particular technical visions, rather than simply providing them with a big screen.

Lately, the company has been moving with a renewed swagger, as embodied by CEO Richard Gelfond, last seen showing off his texts with Tom Cruise to The New York Times. In an interview with The Ringer, Gelfond dismissed a recent Bloomberg story about how several theater chains were considering joining forces to launch a competitor to IMAX, calling it “bad reporting” and claiming he spoke with executives at those chains after the story came out to confirm it wasn’t true. Besides, he says, he wouldn’t feel threatened anyway by people “whose main business is selling popcorn.” As if addressing would-be challengers to the throne, Gelfond circled back to that point while telling a story about how his team convinced the notoriously fussy Hayao Miyazaki to release The Boy and the Heron in IMAX, meeting with him again and again to show off every little tweak in the remastering process until he eventually approved it. “Can you see the popcorn guy at the theater doing that?” he says. “Yeah, I’m losing a lot of sleep over that.” (Gelfond is a New Yorker, if you couldn’t tell.) At a moment when studios are putting the word “IMAX” on posters in a larger font than the actual titles of their movies, Gelfond’s confidence might be justified. But as IMAX charts an ambitious course for its future, fans are left to wonder: Just how big can the premier big-screen company get without losing what makes it special?

Much like “it’s a small world” and the serial killer H.H. Holmes, IMAX got its start at a world’s fair. In 1965, the filmmaker Graeme Ferguson got a call from the Canadian Expo Corporation asking him to make a film for Expo 67, which would be hosted in Montreal two years later. Ferguson set up a production company with his former classmate, the businessman Robert Kerr, and shot the Arctic documentary Polar Life, which he then projected on an immersive 11-screen setup at the expo, where it played alongside filmmaker Roman Kroitor’s similarly multi-screened In the Labyrinth. Ferguson and Kroitor felt they were onto something and launched the Multiscreen Corporation to expand on the concept, but they quickly abandoned the multiple-screen idea in favor of a single large-format projector (the images were never seamless with multiple projectors) and an accompanying camera for just one giant screen—hence the name change to IMAX, which came from the founders toying with the idea of a “maximum image.” Ferguson brought on another former classmate to help with the mechanics, an engineer named Bill Shaw, and the team came up with the core IMAX technology that analog-film lovers like Nolan favor to this day: a gargantuan camera that runs a unique 65 mm film stock, which is three times wider than standard 65 mm film and can pack much more visual information onto each frame than other film stocks, resulting in a higher resolution. The final film reels, meanwhile, are 70 mm, with the extra space containing audio. When projected, the film has a taller-than-usual aspect ratio of 1.43:1, which IMAX’s theaters would be optimized for with steep stadium seating. With the basic principles of its technology established, IMAX was off to the races—sort of.

Long before its Discord acolytes were born, IMAX faced an issue that would vex the company’s leadership for decades. Its business model was premised on showing IMAX movies in IMAX theaters—one was not much good without the other, and it was an uphill battle to get investors to bet big on both. Not long after Expo 67, Ferguson and Co. tried the novel strategy of lying to the Japanese bank Fuji, showing off IMAX’s “offices” in New York and Montreal, which were actually Ferguson’s studio and some rented production space. The ruse worked well enough to secure funding for IMAX’s first film, the 17-minute Tiger Child, which played on a temporary setup at Expo ’70 in Osaka. A year later, the company landed a contract for its first permanent theater at an amusement park in Toronto, where it opened with North of Superior, a Ferguson-directed documentary about Northern Ontario. That theater became a longtime model for subsequent IMAX theaters, which were often in places like museums and aquariums and functioned as immersive exhibits. Visitors could wander in and be transported anywhere for 30 minutes or so, from the depths of the ocean to outer space, thanks to a partnership with NASA in the ’80s that saw astronauts hauling around IMAX cameras.

Hollywood proved more elusive. “People kept telling us nobody would sit still for 90 minutes and watch an IMAX film,” Ferguson, who died in 2021, said in 1997. By the mid-’90s, the company’s founders were in their 60s and had spent over 25 years trying to make IMAX mainstream. In 1994, they sold the company to two American businessmen, Gelfond and Brad Wechsler, who came in with Hollywood ambitions but found themselves relegated to what Gelfond calls “the kids’ table.” He recounts a time when he approached Steven Spielberg about using IMAX, only for him to say, “Call me back when you have 1,000 theaters.” It was the same original problem of not having enough films or theaters to be appealing to Hollywood, which the company then attempted to solve by making it cheaper and easier for studios to work with them through a process called digital media remastering, allowing them to digitally blow up 35 mm films in postproduction to project them in IMAX. After a 2002 rerelease of Apollo 13, the company DMR’d both The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions in 2003 and soon had a pipeline of new-release movies in its theaters. But change came with growing pains.

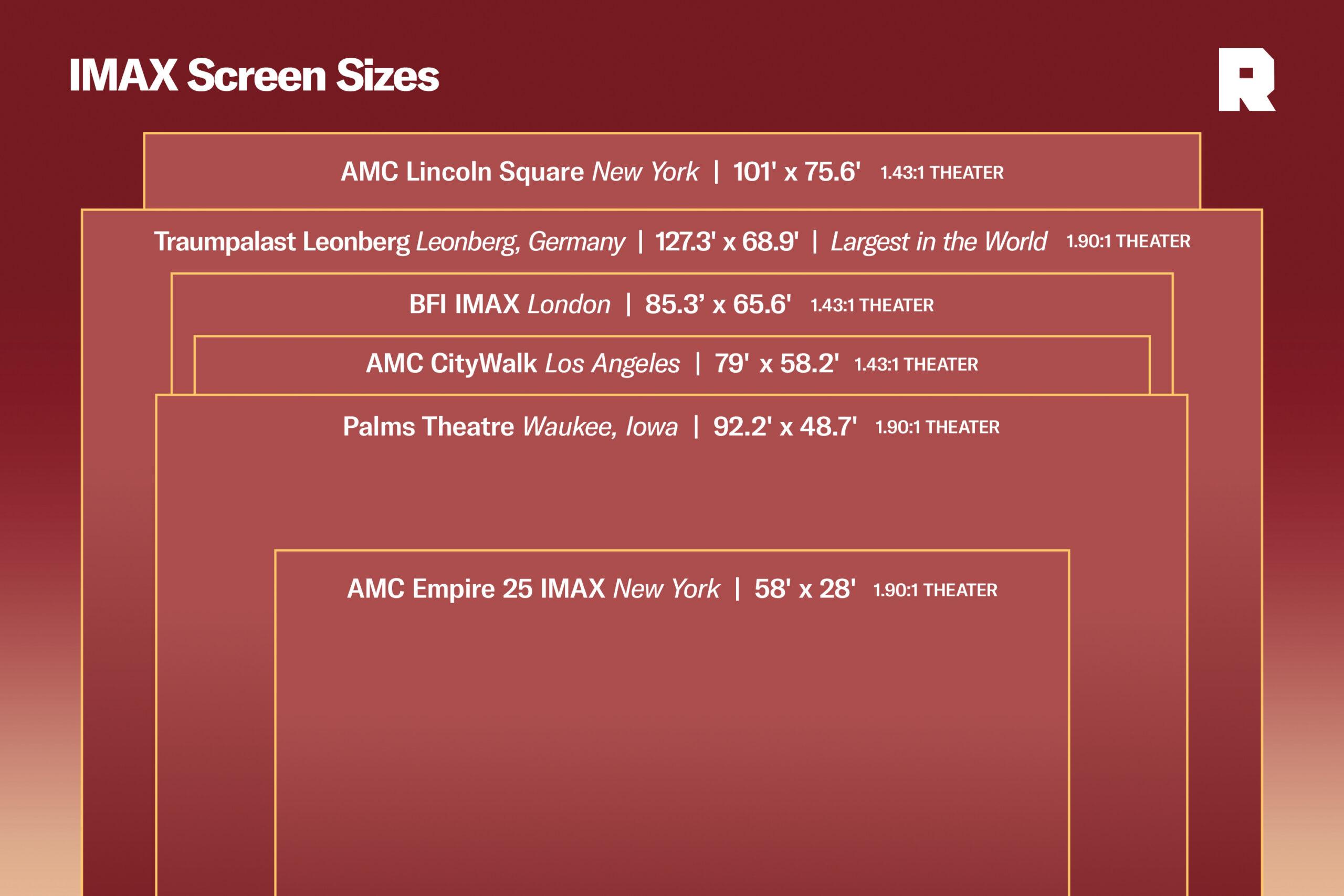

IMAX had secured more films to play, solving one-half of its problem, but it still needed more theaters. The original IMAX theaters had particular specifications: the 1.43:1 aspect ratio, steeply angled rows of seats, and projectors that ran IMAX’s unique 70 mm film stock. They were also big, a quality that largely defined them in the popular consciousness. But those theaters were expensive. In the mid-2000s, Hollywood shifted toward digital, with more films being shot that way and delivered to theaters on digital cinema packages rather than film reels, prompting theaters to phase out film projectors. (By 2014, nine out of 10 movie screens in the U.S. had made the transfer to digital projectors.) IMAX rode the wave, rolling out cheaper theaters with its own digital projectors and screens that were still larger than average but closer in both size and aspect ratio (a wide-screen 1.90:1) to standard multiplex theaters. Many of them even were regular multiplex theaters, which IMAX retrofitted by installing its display technology and sound system and reconfiguring the seating geometry. IMAX still charged premium prices for those theaters and did little to clarify the distinction, initially, for moviegoers. Fans dubbed the theaters “LieMAX” and passed around charts categorizing individual IMAX theaters. Aziz Ansari yelled about it on his blog. When I asked Gelfond about weathering those criticisms, he gave a long-winded answer punctuated by a direct one: “If you’re static, you’re going to die.”

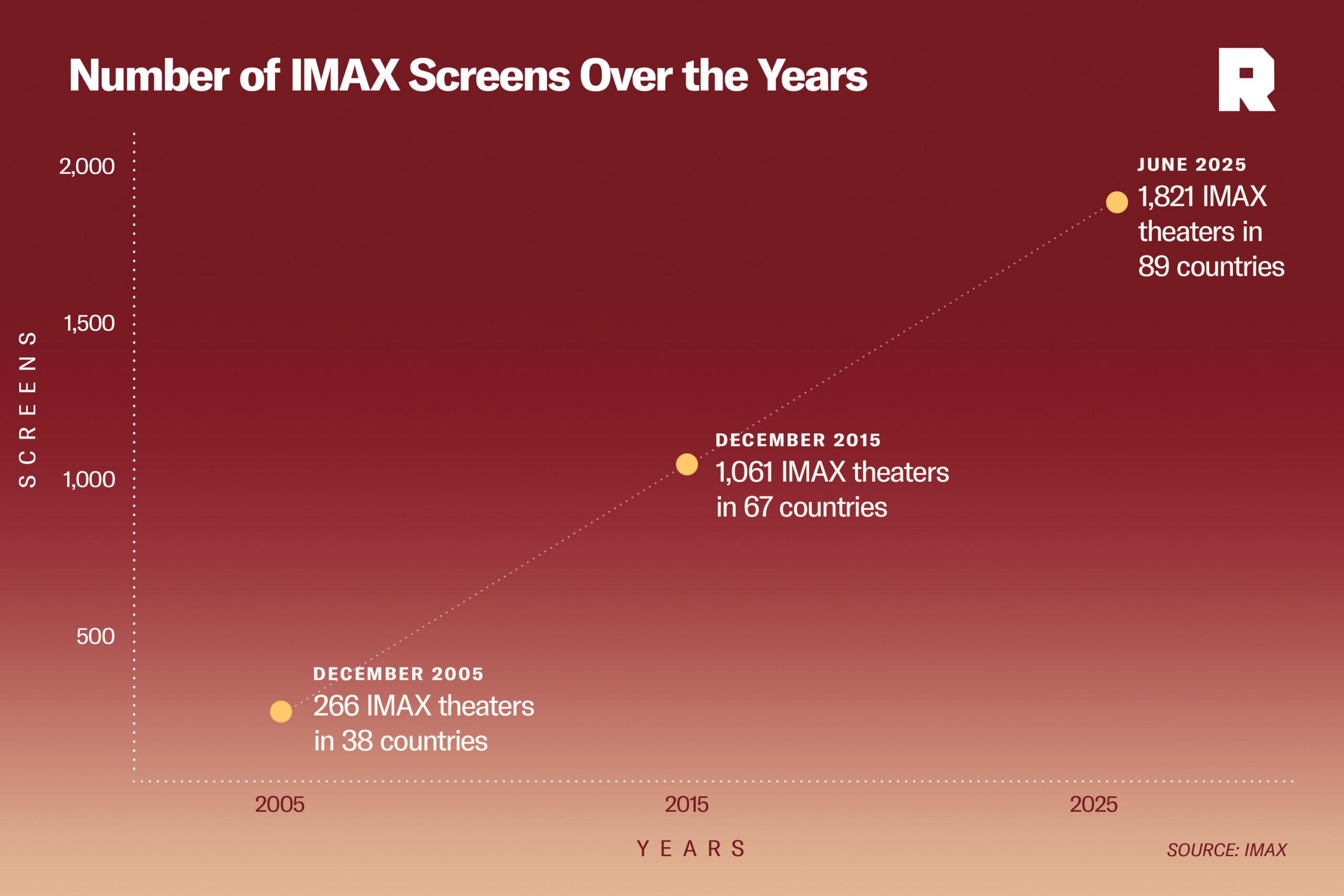

For some, that’s when IMAX crossed a Rubicon, betraying its “IMAX equals massive” reputation and turning its back on analog-film projection. But in terms of world domination, the strategy worked. From 2005 to 2015, IMAX went from 266 commercial theaters to 1,061, and it’s now up to about 1,821, with most of the new screens being 1.90:1 digital theaters rather than “true IMAX.” Even those screens, though, are contractually required to be the biggest in a given multiplex, and the company has fought to ensure that “IMAX” remains a stamp of quality. While there’s no proprietary digital IMAX camera, the company maintains camera specifications for which digitally shot films it’ll show in its theaters and has improved its digital projection to stay ahead of the competition—particularly with the dual-laser projectors in its top-of-the-line theaters.

While purists maintain that IMAX 70 mm still has superior image quality, for mainstream audiences, the thought process behind paying extra for IMAX mainly boils down to “the bigger the better,” according to an email from David A. Gross, who publishes the FranchiseRe newsletter on box office numbers. Overall movie attendance is still down compared to before the pandemic, and theaters have to contend with shortened theatrical windows (meaning movies jump from theaters to VOD faster than they used to) and competition from at-home streaming options. In that climate, IMAX’s promise of spectacle sells, even if ticket prices are often $7 or $8 more than standard theaters. “IMAX is pushing the state of the art for visual spectacle,” Gross says. “That's why they are doing well.”

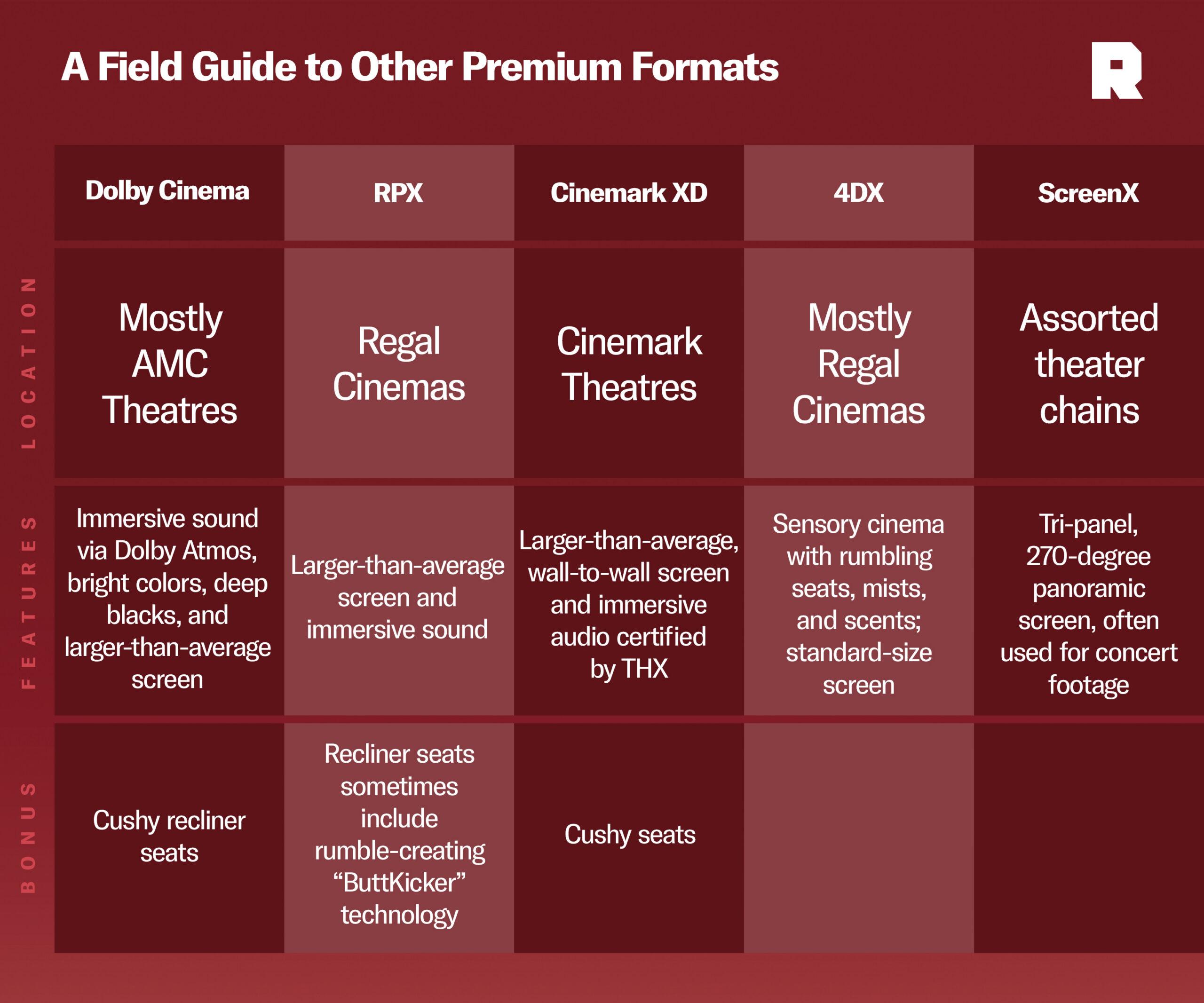

While movie studios and theater chains are profiting off IMAX’s success, it also means forking over more money—each party has to give up to 12.5 percent of its ticket revenue to IMAX, and theaters already pay the company for upkeep of its projectors and screens. On top of that, most major theater chains also have their own premium, large-format offerings: Regal has RPX, Cinemark has Cinemark XD, and AMC has Prime and often houses Dolby Cinema screens. Yet all are still in business with IMAX, which has unmatched “cultural cachet, global growth potential, and filmmaker appeal,” according to an email from senior media analyst Jeff Bock of Exhibitor Relations Co. For AMC Theatres, working with IMAX is a no-brainer, with CEO Adam Aron claiming that each IMAX seat brings in about four times as much revenue as a standard theater seat. AMC houses about half of all IMAX screens in the U.S., and Gelfond also seems to have a bit of a bromance with Aron, who tells me Gelfond christened him “Harry Houdini” in an “important newspaper” (which I cannot seem to find a record of) owing to AMC’s ability to escape crises. When I asked whether he had ever had a disagreement with the notoriously pugilistic Gelfond, Aron said, “Yeah, all the time. And we always work it out.” He later heaped praise on Gelfond: “When he started there, [IMAX] was, like, for museums and planetariums. Now it’s one of the most important forces in entertainment. And I give all the credit for that to Rich.”

If Gelfond’s “If you’re static, you’re going to die” ethos has earned him the respect of his peers, he has also proved adept at courting big-name filmmakers, which has in turn earned IMAX the loyalty of countless cinephiles. But therein lies a curious tension: Even as Gelfond has positioned digital as the company’s future, much of IMAX’s cultural cachet with both superfans and filmmakers comes from its commitment to IMAX 70 mm—the analog format it launched with almost 60 years ago. And when someone like Chris Nolan is involved, that dusty old technology can mean big business.

If you’re a man in his 20s or 30s, as many IMAX superfans are, there’s a good chance 2008’s The Dark Knight played a formative role in your moviegoing life. (Millennial athletes never stop referencing it, while Conner O’Malley and Danny Scharar set their recent period-piece mockumentary, Rap World, in 2009 just because its white-guy protagonists seemed like guys who would have seen it, even though Batman is never explicitly referenced.) It also happens to be Nolan’s first film properly shot on IMAX. After overseeing a DMR release of 2005’s Batman Begins and test-shooting an unreleased IMAX sequence for 2006’s The Prestige, Nolan enlisted David Keighley—IMAX’s longtime tech guru, who passed away this August—to help him figure out how to film six key sequences of The Dark Knight with IMAX’s ginormous, 65-pound film cameras, a first for any feature film. When viewed on a 1.43:1 IMAX screen, this meant that during sequences like the opening bank heist, the top and bottom of the frame would expand, thrillingly, to immerse you more fully in the film. Nolan was hooked and has allowed his IMAX obsession to spiral ever since, bringing his fans and a generation of blockbuster filmmakers with him.

Apart from 2010’s Inception, each subsequent Nolan film has leaned further into IMAX 70 mm, with the filmmaker and collaborators like Keighley and cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema—who has shot every Nolan film since Interstellar—innovating new ways to achieve Nolan’s visions despite the cameras’ impracticalities. (They’re not just enormous—which is why Nolan didn’t use them on Inception—they’re also absurdly loud.) With each release, too, Nolan has further signaled to audiences that he’d really prefer they see his films in IMAX—in 2014, Interstellar was released early in analog-film theaters, including IMAX 70 mm, and went on to break opening weekend records in the format. As the cult of IMAX has grown, superfans have taken on the task of marketing Nolan’s films for him, making all sorts of content about IMAX’s superiority—including this format guide one fan made for 2017’s Dunkirk, which Nolan’s team liked so much they reached out to use it.

Nolan can’t take all the credit for IMAX’s cultish fan base (2009’s Avatar was an early hit in the format, and blockbusters with 1.43:1 sequences like 2011’s Mission: Impossible—Ghost Protocol helped attune viewers to that aspect of it), but he has indoctrinated the most superfans of any filmmaker, in part due to his commitment to analog film, which supercharges the IMAX fandom with the righteousness of fighting for a dying, tactile format in an increasingly digital world—the moviegoing equivalent to collecting vinyl records. In my conversations with seven prominent users across various fan-run Reddit and Discord channels (r/IMAX, IMAX Vanguard, AMC A-List, and its splinter forum, AMCAListTrue), Nolan’s films have been universally cited as an activation point. One fan recalled being a teenager and reading about how Interstellar was filmed for IMAX, then begging his friends to take the two-hour train ride to the nearest IMAX theater with him, while others cited IMAX 70 mm rereleases of the Dark Knight trilogy as a kind of eight-hour baptism. And although the online communities are mostly a place to shoot the shit about aspect ratios and whatnot, they also serve an increasingly vital function: sharing knowledge about ticket drops. In 2022, r/IMAX had 8,000 members—when Oppenheimer came out, that number jumped to 30,000. It’s now at 53,000, with its most recent bump corresponding to the Odyssey drop. As one of r/IMAX’s overworked mods, TheBigMovieGuy, says, “We’re not a customer service team for various theaters. We are a hobbyist group.”

As a responsible journalist, this is where I should disclose that I’m sort of one of these guys—someone who regularly sees new movies opening night in a particular row at a carefully chosen IMAX theater. For years, I’ve benefited from my friend Danny’s IMAX obsession, happily tagging along when he miraculously secures opening weekend tickets at Lincoln Square for Top Gun: Maverick or the Dune films, all while lightly ribbing him for spending his free time on Discord. He is, to put it simply, my IMAX plug. (“You need one!” says Sinners cinematographer Autumn Durald Arkapaw, who once had to sit separately from her mom in a packed IMAX 70 mm showing of her own movie.) Danny’s trick, up until recently, was to be a member of the AMC A-List Discord, which pings users at the exact moment tickets drop for any given movie with such precision that users think its mods have a mole inside AMC. Danny would regale me with tales from the front—including updates on Dub, the guy who never shuts up about seat L21 at Lincoln Square, which Dub says is both dead center and allows for easy bathroom access, since it’s in the second-to-last row with a typically empty accessible seating spot behind it, allowing you to hop out. (Easy bathroom access in a row of 40 consecutive seats is no small thing—anything to avoid the shameful sorry, so sorry shuffle.) Dub eventually got booted by the Discord’s mods for “maliciously” spoiling John Wick: Chapter 4, only for his fellow users to continue saluting their fallen comrade with an L21 emoji. Then, earlier this year, the unthinkable happened: Danny got booted too.

Danny’s crime was unclear—he seems to have gotten caught up in a broader purge, and he has since joined AMCAListTrue, a parallel server for exiled members of the original Discord. That brief intermission, though, made me fearful enough of experiencing IMAX withdrawal (i.e., sudden twitchiness, inexplicable anger at the sight of small screens) that I dived into the fan communities myself, figuring I could bypass the middleman. There’s an element of kayfabe in these groups—does Dub really love L21 that much, or is he playing a character? “I feel a special bond with that chair, man,” he tells me, saying he saw Oppenheimer five times from the seat. His love for L21 started with a genuine quest to find the best seat in the best theater—not L20 or L22, he insists, but the just-right L21. When he went to buy Odyssey tickets, L21 and the surrounding seats were somehow gone before tickets went on sale, sending Dub spiraling: What if that seat was reserved for the Chosen One himself? “If [Nolan] says that’s his favorite seat, I’m done,” Dub says. “I’m never going to have it again.” If an imagined ticket battle with Christopher Nolan sounds like a delusion of grandeur, that kind of winking self-mythologizing comes with the territory. When I pressed Mat (Imp the Dimp), one of AMC A-List’s mods, on whether he really had a mole inside AMC feeding him ticket-drop times, he played coy. “I can neither confirm nor deny …” he said multiple times before saying Adam Aron was his uncle. I said I’d be talking to Aron for this story, and Mat—initially surprised—later messaged me: “Please tell my uncle I miss him.” (AMC CEO Adam Aron is not his uncle.)

Most IMAX superfans don’t have an L21 shtick, but there is a compulsiveness to many of them—a need to see a movie five times in the proper format, or to know offhand how many sequences in a movie were shot in the expanded aspect ratio. It can be a techy form of cinephilia, one where you’re excited not just to see a film in IMAX 70 mm but to understand the mechanics of the projector’s cooling system. And though there are certainly IMAX fans who just want to see everything as big as possible (one told me his dream is to play The Last of Us Part II in IMAX), for many, their obsession is a matter of honoring artistic intent—a distinction that differentiates IMAX from, say, Sphere showing an AI-distorted version of The Wizard of Oz and elevates it above theater-owned premium formats like XL at AMC or Laser at AMC that are basically just display technology. “If an artist has designed [something] in one such way, then it should be seen in that way,” says TheBigMovieGuy, an eloquent British man who calls IMAX’s changing aspect ratios a storytelling device, pointing to an example in Dunkirk where the aspect ratio opens up and communicates how Barry Keoghan’s naive character’s world is tripling in size. IMAX fans obsess over that interplay between the company’s technology and an artist’s intent. And no one made them feel more seen in that obsession than the late David Keighley, Nolan’s IMAX mentor who died in August at 77 shortly after filming wrapped on The Odyssey and whom Gelfond called the “walking embodiment” of IMAX.

In 1971, when he was a newlywed film student, Keighley caught a screening of North of Superior at the original IMAX theater in Toronto with his wife, Patricia, and the two of them fell in love with the format. The pair were entwined with IMAX from then on, first launching a production company, 70MM Inc., to freelance on IMAX’s films and later joining the company directly. Among IMAX superfans, he’s best known as just “David,” the company’s longtime CQO and—more importantly—the guy who answered any and all questions sent to CQO@imax.com. In 2011, Patricia had an idea inspired by those stickers on 18-wheelers that read “How am I driving?” with a phone number included. Since IMAX services its own theaters, why not include a similar message in the credits of its movies alongside the CQO email address? What started as a trickle became a flood, with fans increasingly fluent in IMAX lingo writing to say a projector was dim in an Indianapolis theater, or to ask whether Dune: Part Two would be screening in dual laser. David would pretty much respond to them all, sending fans running back to their subreddits to excitedly share his responses. When he died, Patricia says the inbox flooded with messages from fans saying how much that resource meant to them. (She also said it wouldn’t be going away, with someone taking over for David.)

If Keighley made fans feel like they were a part of IMAX, he also embodied its prioritization of filmmakers, particularly when they were shooting in 70 mm. Collaborating with Nolan on every one of his IMAX films, Keighley was constantly helping him overcome whatever self-imposed challenge the director was facing—be it filming in reverse on Tenet or shooting in black and white for Oppenheimer. If Nolan was filming on location, Keighley would be back at IMAX, waiting on the latest dailies to arrive from set to check the exposure and framing. Once, during COVID, Patricia and David slept in their car after a late night working on Tenet in order to screen the latest print for Nolan first thing in the morning. And when Nolan gave Ryan Coogler advice on shooting Sinners in IMAX 70 mm, he said to make sure Keighley was the one reviewing his footage. Durald Arkapaw, who had never shot on the format before (and is the only woman to have shot a feature film on IMAX cameras, period), found Keighley’s breadth of knowledge essential to making Sinners, particularly given the complex twinning conceit in the movie and the fact that she likes to expose film “very dark.” “Him and Patricia—they’re there every day,” Durald Arkapaw said.

The Odyssey is, in many ways, a fitting culmination to Keighley’s career—the first feature film shot entirely on IMAX 70 mm, made in concert with his closest collaborators. Typical of his work with Nolan, it demanded all sorts of innovations—including quieter, more nimble IMAX cameras designed for the film. When Oppenheimer was released in IMAX 70 mm, Keighley helped oversee a mass mobilization of resources in the name of revitalizing an out-of-vogue medium. Projectors needed to be dusted off and repaired, while IMAX called on its short roster of aging, semiretired 70 mm projectionists, some of whom mainly had experience projecting whale documentaries decades ago at an aquarium IMAX theater. (One such projectionist, Charlie Moss, joked that receiving the call felt like being Clint Eastwood in Unforgiven, saddling up for one last job.) IMAX has already promised even more 70 mm locations for The Odyssey, necessitating an even bigger revival of the format Keighley fell in love with. And while he won’t be there to oversee it, Patricia says, “If you had asked David Keighley, ‘What would you want to be doing the last few months of your life?,’ working with Chris on an epic film like The Odyssey would be exactly what he would say.”

Before Odyssey mania begins in earnest, IMAX has a busy rest of 2025—Avatar: Fire and Ash is sure to do numbers on its screens in December, and Gelfond continues to tout the company’s success at breaking into local-language markets in other countries, which could insulate it from the ups and downs of Hollywood. But as IMAX charts its ambitious course, potential pitfalls loom. Studios, for one, seem eager to push the IMAX branding on movies they’re not so sure about. Earlier this year, the poorly reviewed Rami Malek actioner The Amateur received a big marketing push for its IMAX release despite making no use of the format’s expanded aspect ratios or other qualities that differentiate it. How does IMAX keep its product from being watered down to a gimmick? “You do raise a real-world issue,” Gelfond says, adding that IMAX itself more heavily promotes the movies that make best use of its technology. Back in August, the company also made a potential misstep by signing a deal with Runway AI and hosting an AI short-film festival, a move that angered fans like TheBigMovieGuy who view the company as a custodian of all that is tactile and real left in the film industry. “It hurts a little bit,” he says. “They’re flying so close to greatness.” For his part, Gelfond says his focus remains on putting the audience first, and he says he’s turned down other AI partnerships that were premised on cutting corners.

Future technologies aside, IMAX is leaning into old-school spectacle this weekend with its release of One Battle After Another. An action-comedy flick starring Leonardo DiCaprio that’s as difficult to summarize as its roots in a Thomas Pynchon novel would imply, One Battle is by no means a safe bet for Warner Bros., which gave Anderson his biggest-ever budget of at least $130 million and is clearly leaning into the IMAX angle to sell the film to audiences beyond cinephiles. (Perhaps inspired by Ryan Coogler’s viral video explaining the different formats to see Sinners on, Anderson posted his own guide for One Battle on social media.) As Bauman, One Battle’s cinematographer and director of photography, points out, the film’s native VistaVision format has some similarities to IMAX. It, too, dominated in an era when the film industry was going for spectacle, afraid that audiences would stay home and [gasp] watch their brand-new televisions instead. And while not quite as big or loud as an IMAX 70 mm camera, VistaVision cameras are still big and loud, taking up a chunk of space in close-quarter interiors like bathrooms and requiring a “blimp” to contain the sound on set. Much like with IMAX 70 mm cameras, though, that unwieldiness can create a sense of grandiosity and importance on set that ideally shows up in the film itself, even if it comes at the cost of working with tricky analog tech. “I’d be in that headspace for a bit, feeling like I’m Hitchcock,” Bauman says, laughing. “Then the mag would jam.”

For many IMAX superfans, the company’s greatest asset is its commitment to keeping that kind of old-school, tactile filmmaking alive. Even if VistaVision is a new concept to them, you can bet they’ll be first in line to see One Battle After Another in IMAX 70 mm—Discord users are already losing their minds about the film being presented entirely in the expanded 1.43:1 aspect ratio in that format, and good luck getting a decent seat anytime soon at the Lincoln Square IMAX. Don’t worry about my friend Danny, though. He and I will be seeing it twice this week in that theater, making One Battle After Another the second-biggest IMAX-related event of his year. In July, he proposed to his longtime girlfriend (and my high school friend), Katherine. The dimensions of the diamond? 1.43:1. He swears it was an accident.