On a recent summer night, Mark Ronson DJed at Gabriela, a small club in Brooklyn. Though he’s now a celebrated producer and recording artist, he started out as a DJ in New York City during the 1990s, eventually becoming big in the local scene. While he never completely gave up the vocation, he’s recently returned to his roots, playing all vinyl sets. “I’m not a snobby purist, but there’s that muscle memory of reminding myself of back when I was great or whatever,” Ronson says. “I like this idea of going into a club where I put records together before the night begins. It’s so much more intentional.”

There are, however, certain hazards to DJing that come with age. Earlier this year, he popped two tendons in his arm after trying to turn the stage monitor toward the crowd. And then there’s the tinnitus. “The ringing is so bad now that I go into the club with this sense of apprehension,” Ronson says. “I’m excited, but what’s it going to be like when I wake up tomorrow morning? And because my ears and the use of them is really my main livelihood, I’m starting to be like, fuck, is DJing this luxury that I maybe need to give up?”

Ronson decided to explore DJing and the formative impact it had on his life in his new book, Night People: How to Be a DJ in ’90s New York City, available this week. It focuses on his life before he gained global notoriety following his work on the Barbie soundtrack, his nine Grammys, his collaborations with Lady Gaga and their Oscar win for Best Original Song, his team-up with Bruno Mars on “Uptown Funk,” and his guidance on Amy Winehouse’s Back to Black.

Part memoir, part purposefully outdated resource guide, part celebrity anecdote repository (everyone from Robin Williams to Ol’ Dirty Bastard is on the guest list), Night People deftly chronicles the era when hip-hop turned into pop music and Manhattan discarded its reputation as an urban hellhole. During that time, Ronson emerged as the DJ of the moment—spinning at a funeral in Zoolander, manning the decks at MTV’s Y2K celebration, and appearing in a Tommy Hilfiger ad campaign alongside Aaliyah. In Night People, Ronson writes with an eye toward history, but with disarming humor and honesty, regularly acknowledging his privilege and recounting moments when he acted like a doofus.

Sitting in the Jason Mantzoukas booth at Little Dom’s in Los Feliz on an August afternoon, Ronson wears a ripped Steve Winwood shirt that’s so faded he might as well have it on inside out. He’s got a perennially teenage face and a discombobulating English-American accent. The quiff hairstyle he’s long settled on is perched perfectly atop his head, and the heart-shaped disco ball from the cover of his album Late Night Feelings is tattooed on his right bicep. He admits to being deeply ambitious but is endearingly and enduringly polite. “I always prided myself on being, this sounds very self-involved, a relatively good guy in an industry that could not be,” he says.

Ronson, just a few weeks away from his 50th birthday, is visiting Los Angeles from New York as part of his press tour, but he lived here during the mid-to-late 2010s in a house that’s just a few blocks away. It was during that L.A. stint that one of the events that inspired him to write the book happened. He was at a Passover Seder with a cool actor in his early 20s from Brooklyn. Once dude found out that Ronson came of age in New York during the ’90s, his eyes lit up, and he asked him what it was like.

Back when Ronson started getting into the scene regularly, the uninhibited and outlaw tales of 1970s and ’80s New York nightlife loomed large, passed down by scene veterans who still haunted the clubs. (Ronson’s only firsthand glimpse happened when Keith Haring brought him and his good friend Sean Lennon to the legendary hot spot/conceptual art project Area one night.) Ronson didn’t really consider that his own history might someday become somebody else’s myths. “I understand why the ’90s were an interesting time to be in New York, but it never felt epic,” Ronson says. “Everybody thinks they missed the best era.”

The ’90s nightlife scene was also the last one that wasn’t hyper-documented. There’s barely any video from that time. DJ sets were rarely recorded. Smartphones with decent-quality cameras and digital party photographers didn’t appear until the following decade. “Everything is hearsay and stories,” Ronson says.

Writing the book was also a way for Ronson to sharpen his blurry recollections. At the apex of his DJ career, he was ping-ponging around the city doing three gigs a night, calling the Delancey Car Service to make sure he got to each venue on time. And then there was the fact that he took advantage of all the free drink tickets the promoters passed him and indulged in baggies filled with powdery substances.

Ronson spent three years writing Night People, which is longer than he spent working on any of his albums. He estimates he interviewed 150 to 200 people to get the details right. “I was stuck in the DJ booth all night,” Ronson says of the ’90s. “I remember hearing the stories of what happened when Biggie showed up at the door with 50 dudes, but I needed my memory jogged.”

Night People’s most obvious reference point is Anthony Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential, the beloved raconteur’s book from 2000 that details the realities of his life as a working chef in New York City. Similarly, Night People is a personal history that’s filled with discourses on process and practical information. Ronson describes which stylus needles different types of DJs prefer and the purpose of slipmats. One section covers the New York City Cabaret Law that limited how many venues could allow dancing and the measures promoters and DJs would take to outwit Rudy Giuliani’s cops looking to enforce it. There’s even a section where Ronson goes into deep detail about the most efficient way to get three heavy crates of records from inside your apartment onto an elevator without either door closing. It’s all fascinating.

But even more revealing are his insights into the psychological makeup of the type of person who excels as a DJ. When covering his early gigs as a college student at Vassar, he recalls how the booker of the on-campus dance club once asked how he was able to command the crowd so well. In response, Ronson writes, “I shrugged. I didn’t feel like saying, ‘Because I have this weird knack for reading people, I need to be in control, and I kind of love the attention that comes with it.’”

Those who shared this mindset often sought each other out, and another recurring theme in Night People is how much camaraderie existed among the DJs. Though they were competing for the same jobs, there was an understood ethos of shared knowledge. The community couldn’t advance without passing on its musical and technical insights. “We spent our days together, we spent our nights at each other’s gigs, and downtown New York was so alive,” says Ronson.

Max Glazer started DJing in the city around the same time as Ronson and considered him a peer. “You could make friends over digging for records,” Glazer says. “That was a point of bonding and connection for the people that were into that. It wasn’t a cool thing to be doing. In order to get any kind of decent record collection and be decent at DJing, you really had to be on some nerd shit.”

Back then, there was no model for how to make being a club DJ a viable, long-term career option. “There were not 60-year-old DJs; there were not retired DJs,” Glazer continues. “It was also very much of the times. It required apprenticeship. You could not understand and learn this in a vacuum. You had to engage in it. You had to study and learn it. The only way to have any standing in it is you had to do it, and the only way you could do it was by someone showing you.”

Nightlife culture has changed substantially during the past quarter century, and the barrier to entry to become a DJ keeps getting lower, even on a purely equipment level. Vinyl records have mostly been replaced by digital software, streaming services, and USB sticks. A basic DJ controller retails for barely over $100. YouTube and TikTok are filled with skills tutorials. Ronson knows that a lot of the information in Night People won’t be relevant to today’s aspirants. “It’s almost a little tongue in cheek, the subtitle of the book—How to Be a DJ in ’90s New York City—because that's literally the most useless how-to ever,” he says.

There are, however, lessons woven within it that are still applicable today. He breaks down the etiquette of why opener DJs should leave the hits to the headliners. He details his mental process of finding the connections between tracks and how they might mix together when planning a set. Most importantly, Ronson notes that among downtown New York DJs back then, 75 percent of the records they played were identical. “The other 25 percent—the records that added an extra layer of personality—defined our style,” he writes.

Ronson created his defining quarter by convincing crowds who came to hear hip-hop, soul, and Jamaican music that rock and new-wave tracks made sense in his mix. His eureka moment happened at the club Cheetah, when he pulled off a transition from the Notorious B.I.G.’s verse on “It’s All About the Benjamins” to the thunderous riff of AC/DC’s “Back in Black.” From then on, whether it was Joan Jett or the Smiths, everything was fair game.

“There were certain records that DJs of that time wouldn’t really play, but he had a carte blanche type of thing going for him,” says Goldfinger, a longtime New York DJ and a cohost of the ROAD Podcast. “He would get certain records over, and I would have never thought about playing that record.”

Originally, Ronson was going to title his book 93 ’til Infinity, after the Souls of Mischief track, because that was the year he started DJing. “I love that song, but that almost sounds like a cool indie Sundance movie about a young Black high school kid coming of age in Oakland,” he says. Instead, he chose Night People, which was the name of the record label and longtime party at Le Bain put together by Blu Jemz, Eli Escobar, and Lloydski.

Ronson and Jemz knew each other going back to their high school, aspiring-club-kid years, when Ronson was getting lost in K-holes at the Limelight and Jemz sported a blue Afro. In the ensuing decades, the two would often DJ and hit parties together. Jemz died in 2018, and as Ronson prepped to play a posthumous birthday celebration in January 2022, he committed to writing the book. He wanted to record the stories while he still could. But even in the process of compiling Night People, more friends he planned to speak to for it passed away, including DJ Clark Kent, DJ Neva, and Fatman Scoop.

The title Night People also refers to Ronson’s interest in what compels a certain type of individual, whether they’re in the DJ booth or on the dance floor, to spend so much of their life in clubs. “We were all going out at night for a reason,” Ronson says. “Some people were going out to get laid, get fucked up. Some people like to dance. And a lot of us, the daytime was a little bit too harsh of a reflection of what we felt were our shortcomings in life. Nighttime gave us all this swagger or maybe this extra coat of armor.”

Ronson was born in London in 1975. He grew up in a Jewish household, and his mother, Ann Dexter-Jones, and father, Laurence Ronson, were a groovy and affluent couple renowned for the raucous, celebrity-filled parties they threw at their place on Circus Road. When the parties weren’t happening, the house was often filled with the sound of his parents yelling and slamming doors. After they split up, Ann began a relationship with and eventually married Mick Jones, the English guitarist, songwriter, and producer of the rock band Foreigner.

Ann moved to New York City, where Jones lived, in the early ’80s, bringing Ronson and his twin sisters, Charlotte and Samantha, with her. The family settled into a massive apartment on Central Park West, paid for with the success of songs like “Cold as Ice” and “I Want to Know What Love Is,” and they were eventually joined by Ronson’s half-siblings, Annabelle and Alexander Dexter-Jones. The parties and after-parties continued at this home too, but even more intriguing to Ronson was Jones’s home studio, where he gave his stepdad feedback and started to make his own productions.

Ronson played in bands in high school, most notably with the Living Colour–inspired group Whole Earth Mamas, but he realized his friends’ abilities on their instruments were accelerating at a far faster rate than his. He became increasingly devoted to hip-hop and the clubs around the city that allowed, or ignored, underage patrons. As a gift for getting into college, his mom bought him his first pair of turntables and a mixer, and Ronson started finagling gigs in New York before he even left town for his first semester at Vassar.

The family eventually moved to a smaller apartment farther uptown. One of the building’s other residents was the club impresario Peter Gatien. His teenage daughter, Amanda, booked the newbie Ronson at the massive Club USA for the weekly party her dad handed over to her.

Ronson spent much of his time at Vassar taking the train back into the city for gigs and ended up transferring to New York University, though he would drop out before graduating. Instead, he hustled DJ spots wherever he could: model parties, bars filled with the after-work crowd (“Validation is validation, even in a pair of Dockers,” he writes), and the occasional prized downtown gig thrown by promoter Bill Spector. His big breakthrough happened when he became the guiding DJ at Sweet Thing, a soul party whose clientele, celebrity and otherwise, started demanding more and more hip-hop.

Even amid recounting his rise in Night People, Ronson continually returns to stories where he embarrasses himself in front of his heroes by always saying the wrong thing, like when he tried to bond with A Tribe Called Quest’s Q-Tip by blowing up a sample that he used. “Those are funny, and those are things people want to read,” Ronson says. “That’s like a hook in a song—Oh, this guy played himself out in front of Jay-Z.”

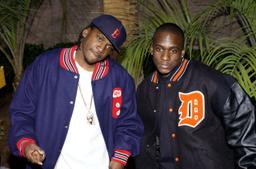

As Ronson’s reputation and talent grew, Sean Combs (or Puff Daddy, as he was known back then) was on a mission to dominate New York’s entire social world, from Harlem to the Hamptons. Combs added Ronson to the rotation of DJs he hired for his parties. “He had different DJs for different scenes,” Ronson says. “He had Kid Capri for this party and [Funkmaster] Flex for this one, but anything below 14th Street, I was his guy.”

Of course, associations with Combs take on another dimension in 2025, as more and more accounts of the music industry mogul’s history of abuse and vile behavior become public. “I was well into the book when the allegations came out,” Ronson says. “Obviously, I was never at anything late night or any of the shit that went off, but it’s like, OK, how funny is it now, this story that I ate a weed cookie by accident at Puff’s house and went into a kind of stupor while I was supposed to be DJing. Now a lighthearted story about being drugged accidentally at Puff’s house doesn’t quite hit the same way. It’s the only time that I really had to come out of the really in-the-moment diaristic nature of the book to be like, We would find out shit that was crazy, and I did not know that.”

Ronson also doesn’t dismiss the realities that set him apart from many of the other downtown DJs: He was young, white, and good-looking, and he came from a rich family with connections. Those realities both gave him certain advantages and made others dismissive or wary of him. In writing Night People, Ronson learned he couldn’t ignore either perspective.

During a family Christmas party in 2024, he started talking to Abe Streep, a respected journalist and author who is a cousin of Ronson’s wife (the actress Grace Gummer) and nephew of Ronson’s mother-in-law, Meryl Streep. Abe offered to read a draft and then gave him some notes. “His main takeaway was, ‘You need to really make sure you’re running these two parallel lines when you’re working on this book: (a) Yes, I came from fucking money, and (b) I worked my ass off to get here,’” Ronson says. “Those were things I was probably doing but maybe pussyfooting around a little, and I realized I needed to really own those things.”

The reality is that Ronson wouldn’t have been able to get as far as he did in the world of ’90s DJing if he had just coasted on his background. As Glazer says, “You have to be able to do the thing. And I would always point out, I’ve been in these clubs with Mark—I do the thing, he does the thing. You read the room. You rock the crowd. You’ve got to deal with someone from Bad Boy coming up and telling you to play this and play that, people threatening you to play songs, and wild shit.”

In May 2000, New York published an issue with Ronson on the cover, draped in an American flag, with the line “The King of Spin.” But much of the article focused on his family, particularly his mother, Ann, who was still a major social presence around New York City. “That was a real lesson in hubris and ignorance," Ronson says of the personal and public reaction to the article as he walks down Hillhurst Avenue to get a post-meal coffee.

At the time, the phrase “celebrity DJ” was just becoming popular, though it wasn’t always clear whether the “celebrity” referred to the clientele or the DJ. The Hilton sisters were everywhere, and the older generations of New York’s power and media establishment couldn’t wrap their heads around what they did or how they lived. In the New York article, as Ann goes to the club Moomba with her children and hypes up everything from Mark’s and Samantha’s DJ careers to Charlotte’s T-shirt line, she comes across more like a proto–Kris Jenner than the eccentric and proud mother that she probably was.

Journalist Nancy Jo Sales wrote the piece. She had already profiled figures like Funkmaster Flex and Russell Simmons for the magazine, as well as penned the infamous “prep-school gangsters” article that Vampire Weekend would reference in a song title decades later.

Sales first saw Ronson DJing at a club called Den of Thieves on the Lower East Side when she went there one night with members of the Wu-Tang Clan. “The late ’90s saw hip-hop crossing over to the masses of white people who didn’t know yet how great it was—how profound. It was a moment,” she writes in an email reflecting on the article. “And, I thought, Mark Ronson was sort of a symbol of that moment, in New York. That’s why I argued to put him on the cover. His popularity in two sectors of society seemed culturally significant. I always knew he’d be a huge star; he was just so talented and appealing. All the stuff in the article about his family and connections were more what interested my editors. And that was the stuff that got the story to be on the cover, frankly. Draw your own conclusions as to what mattered to the people I was working for.”

When the article was published, Ronson was already planning to concentrate on producing. “There was also something kind of shallow and superficial about the scene at that moment where jiggy culture took over,” Ronson says. “When everything was just that bottle service hip-hop, I actually wanted to stop DJing altogether.”

“It was kind of like a break in the chain in some ways,” Glazer says of turn-of-the-millennium nightlife in New York. “It was much less about being able to control the room and make that room do what it needed to do. It then became about the promoters who put the people in the room.”

While Ronson never totally stopped DJing over the years, since completing the book, he’s been doing more gigs despite the impact on his body. “I’m coming home now, a 50-year-old man, at 3:30 in the morning, crawling into bed, trying not to wake my wife, and then getting up at 6:30 with two toddlers,” he says.

When he hasn’t done a set in a while, he’ll sometimes hit up a couple of the younger DJs he’s into to get some intel. “I’ll be like, Yo, what’s killing in the clubs right now? And they’re like, The same fucking shit you were playing in 2003,” Ronson says. “So it’s interesting that those records, especially for a hip-hop R&B crowd, are still the things that are moving it. And I like those records probably more on a whole than the newer records.”

But there’s still something about finding a new connection he wasn’t expecting, another entry to slip into the ever-expanding mix of dope shit. During one recent set, he spun Tyler, the Creator’s “Big Poe,” the Don’t Tap the Glass opener that sounds like an early Neptunes production. “It was so fun to have everybody coming expecting this one thing and then to just drop that,” Ronson says, his voice gently rising in excitement. “There was this oh shit, this euphoria to be playing it.”