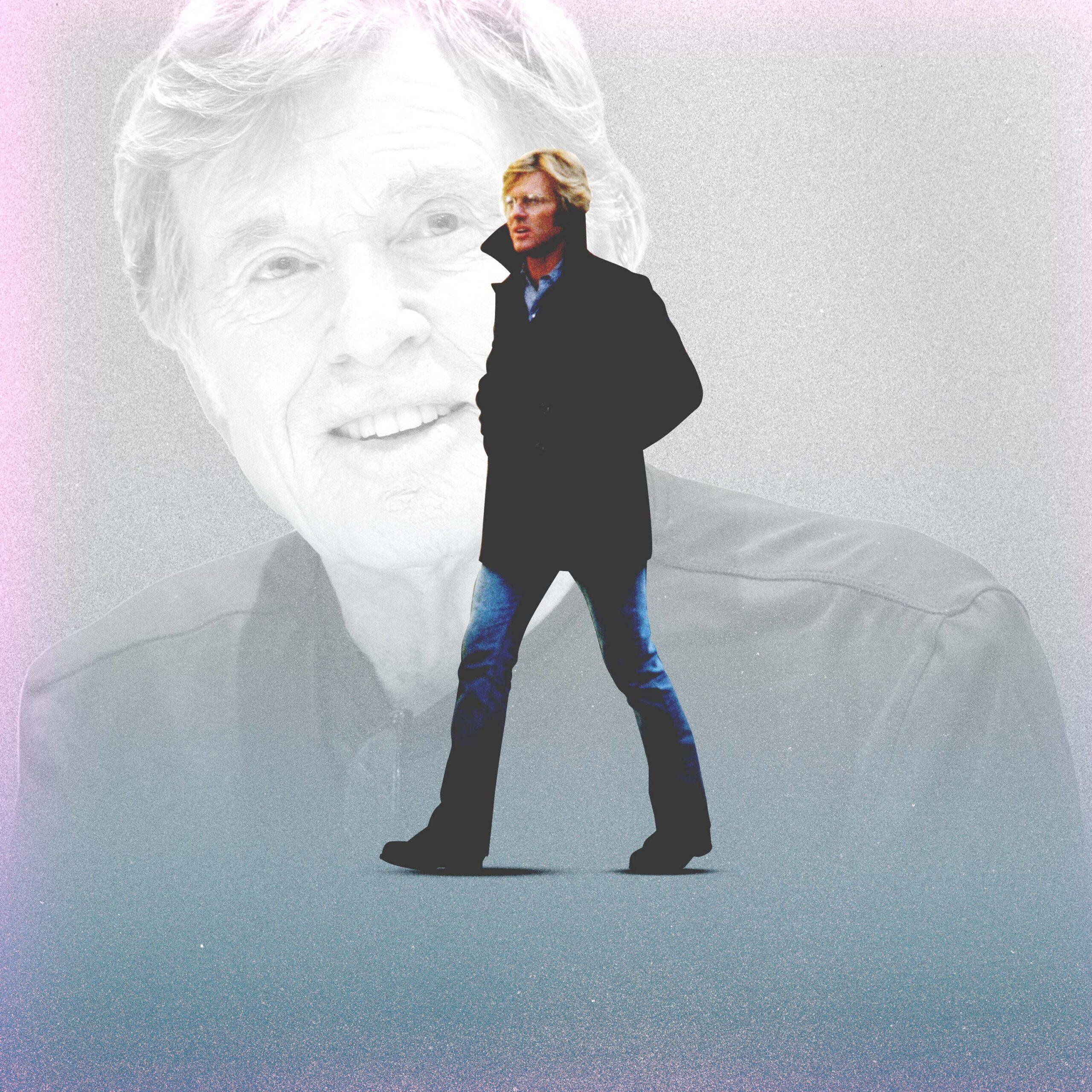

It’s about decency, isn’t it? For all the privilege Robert Redford enjoyed in his life—and between the California good looks, the patrician bearing, the fame, the ranch, the awards, the money, all of it, he must have been one of the most privileged human beings ever to walk the earth—he always seemed like an essentially decent man. On-screen, he excelled at playing decent men caught up in circumstances beyond their control, and he excelled, conversely, at sneaking a note of decency into the characters of outlaws and crooks. He seemed reasonable, even when he was acting in patently unreasonable ways. He could play a cereal company mascot who steals a horse in the middle of a disco routine, as he did in 1979’s The Electric Horseman, or he could play an Old West mountain man who embarks on a solo vengeance quest, as he did in 1972’s Jeremiah Johnson, and you’d never think, What the hell is this lunatic doing? You’d think, Hey, that handsome guy’s got the right idea.

Redford, who died on Tuesday at the age of 89, never possessed the smirking defiance of Jack Nicholson or the stony ruthlessness of Steve McQueen. He never had the rebellious streak, rooted in sheer orneriness, that his friend and costar Paul Newman called up in movies like Cool Hand Luke and The Hustler. When the bad guys came to town, Newman understood that the good guys sometimes had no choice but to fight and that fighting could be a pleasure; Redford, by contrast, could be in the middle of a brawl and still give you the impression that he’d rather resolve things through calm deliberation. But somehow that hint of moral reluctance, that slight hesitation on the threshold of cinematic adrenaline, never made him seem weak or contemptible. It made him seem trustworthy. Who better to decide when to throw a punch than the guy who'd rather not fight at all? He was a golden boy with a heart of gold.

Which isn’t to say that he didn’t take down large numbers of enemies as the Sundance Kid, or that he couldn’t sell a fight scene convincingly. Almost no one gets to be a male star in Hollywood without pretending to kill a disturbing number of people. But he still managed to seem less at home with violence than any male star since at least Jimmy Stewart—and maybe less than Stewart, since the killing in Stewart’s movies usually helps to restore justice, while in Redford’s, made a few decades later, things are seldom so clear.

The peak of Redford’s career, in the 1970s, coincided with a shift in how Hollywood perceived masculine toughness, and Redford carved out a peculiar space for himself between the old and new ideas. In the old framework, toughness was mostly a matter of how much damage you could take. Think of Humphrey Bogart: as tough an on-screen presence as anyone’s ever been, but not because you picture him clearing out waves of enemies, Call of Duty style, with his wide-ranging combat skills. Bogart was tough because you knew he’d never break. He’d endure everything you threw at him and keep going until he’d beaten you. Sometime around the early 1980s, tastes changed, and toughness became a matter of how much damage you could inflict, not how much you could endure. Arnold Schwarzenegger never came close to Bogart’s hard-bitten stoicism, but he never had to; the Terminator might have been relentless, but it wasn’t vulnerable to harm in the way a normal man would have been. It just rolled in and leveled everything that opposed it.

And where was Redford within that shift in film’s ideal of masculinity? He was nowhere, really; that’s what was so wonderful about him. He never seemed like someone who could take or dispense a lot of damage, which made the stakes in his films higher and the outcomes less rote. People sometimes use Redford as an archetype of the newly sensitive male of the 1970s, but I don’t think that’s it, exactly. He may have been more in touch with his feelings than, say, Clint Eastwood, but the hesitancy he brought to violence also appeared around strong displays of emotion. When, as the very nonlethal CIA researcher Joe Turner in Three Days of the Condor, he comes back from grabbing lunch to find that all his colleagues have been murdered, he doesn’t wail or emote or shoot for Oscar-reel acting. He lets you see that he’s scared; otherwise, his reaction is almost as muted as Bogart’s would have been. When he plays love scenes, with Barbra Streisand in The Way We Were or Meryl Streep in Out of Africa, he’s as reserved as Cary Grant. There’s always a sense of discretion with Redford, of withholding, pausing, watching. He fought to play the title character in Jack Clayton’s 1974 adaptation of The Great Gatsby, but the casting was a mistake. Gatsby is a guileless dreamer who invents a new identity, but Redford was neither guileless nor aggressive enough to refashion himself. The plane of liquid amorality where Gatsby lives isn’t one Redford can reach. His characters know who they are and are always weighing how much of what they know to share with the audience.

Redford may not have embodied sensitivity, precisely. But the way he carried himself on-screen—strong but not tough, confident but not quite at ease, vulnerable but not expressive—still enabled him to create a new type of Hollywood hero, one more careful, more thoughtful, and less driven by instinct than the ones who came before. Redford’s characters aren’t compelled by impulse so much as by reflection; even when they’re brazen risk-takers, like Johnny Hooker in The Sting, their first move is usually to lie low and make a careful plan. Along with his Bob Woodward in All the President’s Men, Redford’s best part is Turner in Condor, because the character brings to life the full range of classic Redfordian traits. He’s in terrible danger. He’s on the run. He’s trying to do the right thing. He’s caught in a plot he doesn’t understand. He’s smart and brave but out of his depth. He’s dealing with enemies more merciless than he is, and you know all along that he could be killed at any moment. He perseveres because he has to, and he wins because he outthinks his enemies—but his victory is partial, marked by a sophisticated uncertainty rather than by cathartic clarity. Life is not easy for a decent man.

One refrain I’ve heard repeatedly in the wake of Redford’s death is that he was the most influential actor of his generation, thanks to his support for independent film, his work as a director, his advocacy for the environment and for Native American rights, and his role with the Sundance Film Festival. I think that this is probably true, and I keep wishing his screen persona had been equally influential. In many ways, Redford’s role in Hollywood was to imagine what it would look like for the ultimate historical winner—a tall white man with a million-dollar smile, born in the United States near the middle of the 20th century, too young to fight in the World Wars, blond, handsome, popular, rich—to be driven by his advantages not to arrogance and entitlement but to self-reflection and a desire to do good. Few movie stars have ever made responsibility more central to their identities on and off the screen; we could use more men like him now.