Not much was happening the spring of 2015 in Waco, Texas, besides the ongoing expansion of Chip and Joanna Gaines’s farmhouse empire. But that May, the college town got its semi-regular shot in the arm: A fight between motorcycle clubs broke out at the local Twin Peaks, and nine bikers ended up dead. The headlines were lurid: A spread of increasingly medieval weapons was found stashed about the Twin Peaks restaurant after the fight; the melee apparently broke out over which group, the Bandidos or Cossacks, got to wear a “Texas” patch on their jackets; and it became clear that the police, who’d surrounded Twin Peaks in anticipation of a shoot-out, might’ve been the ones who exacerbated it. The fight happened at the tail end of my junior year at Baylor (also located in Waco), and to us students, the dueling motorcycle clubs were obviously frightening and ultimately tragic, but more than that, they were colorful and outlandish, the stuff of Pee-wee’s Big Adventure or Sons of Anarchy.

Episode 2 of Task, “Family Statements,” centers on another violent biker gang: the Dark Hearts, the motorcycle club that Robbie has been targeting with his trap house robberies. A shot of the Dark Hearts taking over the road on their way to a “church meeting” calls back to the long-running image of these clubs: They’re militant but lawless crusaders who are out looking for a fight. It’s a trope that’s existed since paranoia spread that the Hells Angels were out to pillage your town and steal your daughters out of their beds. And while it may be based in reality, that iconic mythology of the violent, take-no-prisoners motorcycle gang built velocity in pop culture, from The Wild One to Angels From Hell to Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, and now all the way to Task.

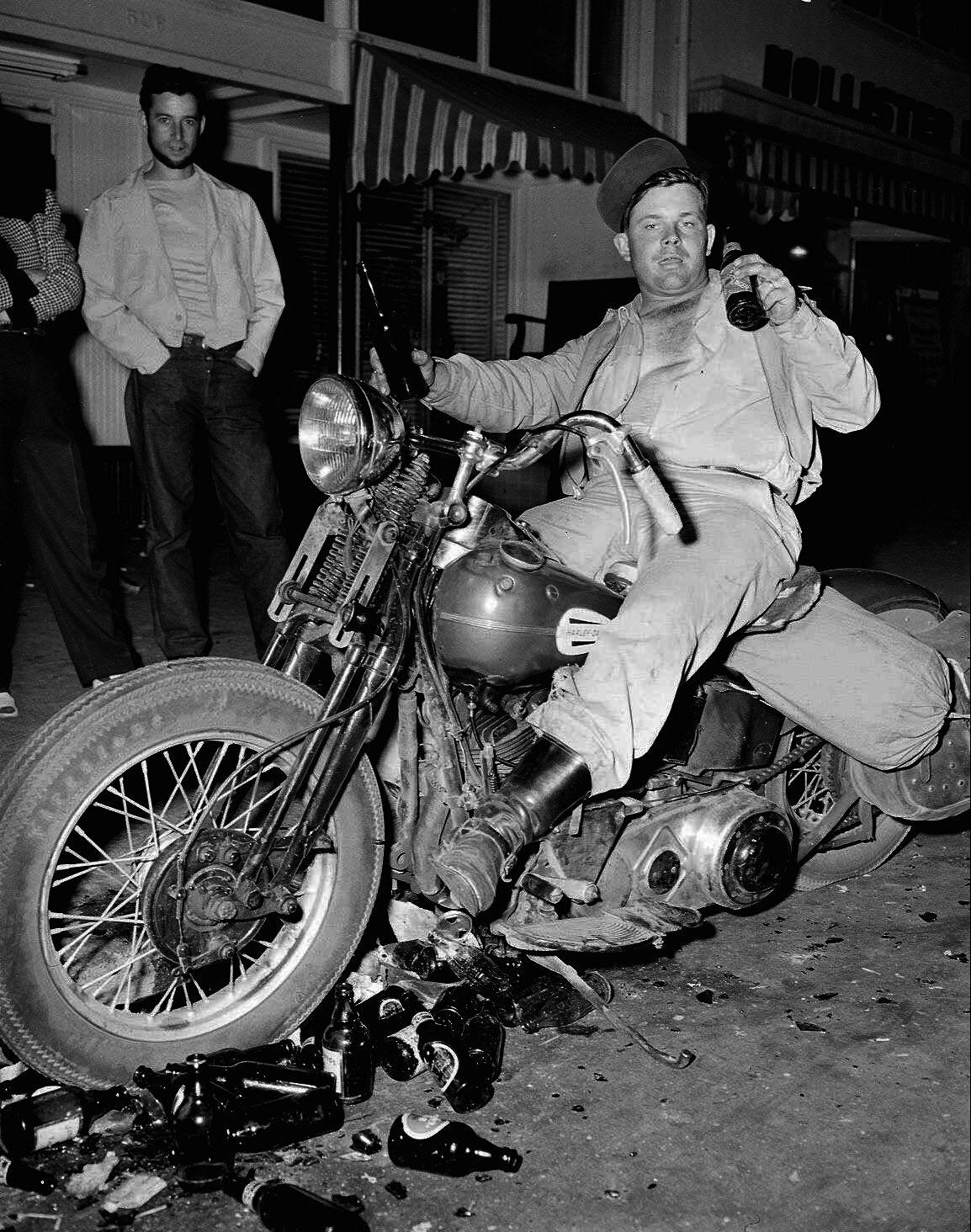

The first motorcycle clubs started forming in the 1920s and ’30s as relatively Pollyanna-ish social groups. Biker groups initially banded together to share their appreciation for motorcycles, to organize for looser restrictions on riding, and to put on rallies and competitions (some still running today). From the early days, these clubs attracted veterans settling back into civilian life, which was why their numbers swelled after World War II, when soldiers who were craving the structure and adventure of the military—and who were able to afford cheap bikes because of military surpluses—started joining roving bands like the Outlaws in Chicago and the Hells Angels in California. But it was a 1947 rally in Hollister, California—the first so-called gypsy tour since the end of World War II—that made bikers’ brand as violent outlaws stick. Over a July 4 weekend, the Pissed Off Bastards of Bloomington, the Boozefighters, and the Market Street Commandos all descended on Hollister and, according to the San Francisco Chronicle, laid waste to the town. Newspaper stories about the rally described broken bottles littering the streets, hellions racing headlong into bars and restaurants, and indecent exposure that made locals recoil in horror. The articles describe the bikers a lot like the police talked about Rambo in First Blood (who, fittingly enough, also made his getaway on a motorbike): The club members were unwelcome drifters, veterans who didn’t belong in the small, idyllic towns that they ravaged with their bikes. In the wake of the rally, the American Motorcyclist Association said, maybe apocryphally, that 99 percent of bikers were decent, law-abiding citizens; the remaining 1 percent were responsible for the hooting and hollering in towns like Hollister. Ever since, “outlaw motorcycle gangs” like the Pagans, Mongols, Hells Angels, Cossacks, Outlaws, and Bandidos have called themselves “1 percenters” as a point of felonious pride.

With a leading man in Marlon Brando, the 1953 movie The Wild One turned the miscreant biker into a bona fide mythical figure. The movie was inspired by the Hollister rally, and it gave life to the idea of the motorcyclist as the family man’s worst nightmare (and his daughter’s forbidden fantasy). When asked what he was rebelling against, Brando’s Johnny Strabler just said, “Whaddaya got?”—the ultimate credo of the nihilist biker who had no MO except to ride around and destroy whatever got in his way. (In 1966’s The Wild Angels, Peter Fonda expanded on that creed before, naturally, trashing a church and killing a preacher: “We wanna be free. We wanna be free to do what we wanna do, … and we wanna get loaded, and we wanna have a good time. That's what we're gonna do. We're gonna have a good time. We're gonna have a party!”) Reviews of The Wild One bought into the fearmongering: “[The Wild One] is a frightening picture … that revolves around conflict between young, seemingly hopped-up ruffians and the mob lynch law spirit of the community’s staid, respectable citizens, with the police helplessly standing by.”

The Wild One and its imitators inspired more hopped-up young ruffians to join the leagues of real-life biker gangs; as former Hells Angel Chuck Zito said, “We wanted to be like the gangs depicted in movies—tough sons of bitches who didn’t like authority and who weren’t afraid of anyone.” And in 2024’s The Bikeriders, gang leader Johnny (Tom Hardy) is inspired by The Wild One and its anything-goes rebellion to start the Vandals (based on the Chicago Outlaws).

Hundreds of biker gang movies cranked out in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s amplified Brando’s mythology while the clubs themselves expanded throughout the country. These bikesploitation movies (many coming out of Roger Corman’s production stable) leaned on some consistent tropes: down-and-dirty brawls over pretty much nothing; church desecration; a middle finger pointed in the general direction of authority; rip-roaring bike rides past slack-jawed hayseed locals; men with unkempt hair; “old ladies” whose sole purpose is to get roughed up; real Hells Angels filling out the cast; heavy ’70s needle drops; grimy leather; Peter Fonda; and character names like Heavenly Blues, Stinkfinger, Cueball, and Chopped Meat. And the genre kept finding new, inventive ways to stoke fears about biker gangs: Movies like Psychomania and Satan’s Sadists turned them into literal agents of the devil, envoys from hell sent to wreak havoc here on earth.

Through all these movies, there’s a tension between whether the bikers and their gangs are being, sometimes literally, demonized as hedonistic freak shows or glorified as icons of the counterculture. And as these gangs appeared more and more dangerous on-screen, their real-life counterparts were engaging in increasingly illicit activities, trafficking drugs and becoming more organized in their approach to the criminal underworld.

The motorcycle movie that’s probably most associated with this era is Easy Rider. While it might not feature a rioting gang like its B-movie ilk, it captured the ethos of bikers who just wanted to ride coast to coast and peddle drugs along the way, free from the restrictions of polite, small-minded society. “What the hell is wrong with freedom?” Billy (Dennis Hopper) asks when George (Jack Nicholson) explains that small-towners hate him just because he’s liberated from their conservative politics and haircuts.

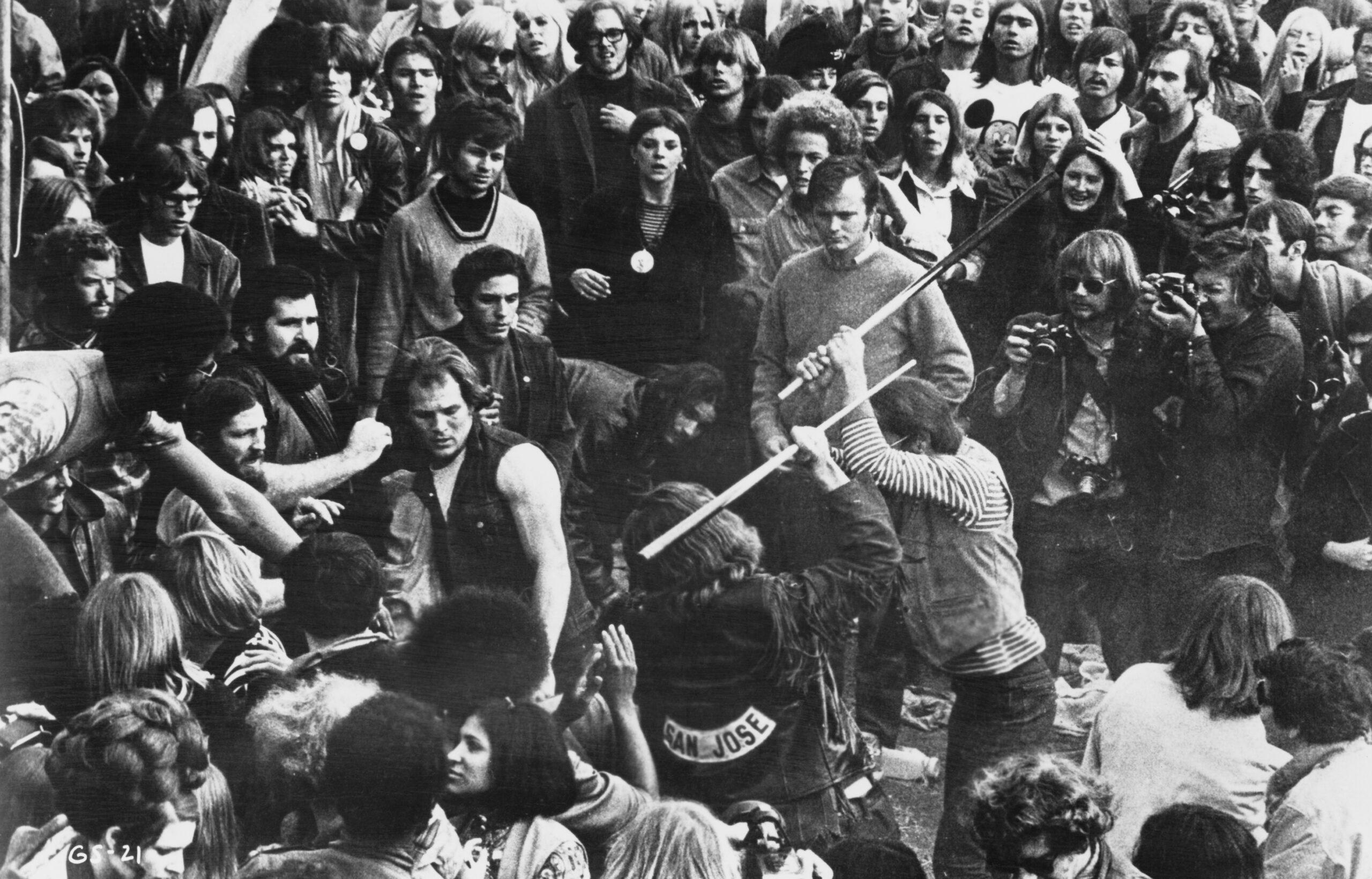

Anyone who’s ever been flanked by bikers gunning it on the freeway can probably understand what’s wrong with a little freedom: If you’re not buying into their version of it, freedom just feels a lot like chaos. Gimme Shelter, the 1970 documentary about the free concert at Altamont Speedway, showed where all that chaos could lead. It was a look at the Hells Angels in reality, not just when they played swashbuckling versions of themselves in Hells Angels on Wheels or Hell’s Angels ’69. The gang had been hired to do security for the Rolling Stones during their set, but the free-love show rapidly devolved into clashes between the audience, the musicians, and the Stones’ so-called security team, who wielded pool cues to fend off the teeming crowd (the Grateful Dead refused to go on at all after Jefferson Airplane’s frontman got hit in the face by a biker). And then, most infamously, Meredith Hunter was stabbed to death by a Hells Angels member after he pulled out a gun while the band played “Under My Thumb.” All of it was captured on film, and Gimme Shelter became a visual death knell for any romantic ideas about easy-riding bikers and the counterculture of the 1960s writ large.

Bikesploitation movies mostly petered out in the 1980s, the glamour worn off due to overuse, the increasingly apparent seediness of biker gangs, or society’s general shift to the right during the Reagan ’80s. Biker gangs still showed up as postapocalyptic raiders in the Mad Max movies or as cartoonish villains in Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, which played on long-running clichés of beefed-up, volatile bikers. Those movies, in keeping with the go-for-broke 1980s, played up the biker to bigger-than-life proportions, but he wasn’t an ideal of freedom and rebellion anymore—just a symbol of violence.

But the most recent revival of biker gangs on-screen has brought them down to a more grounded scale. Shows like Sons of Anarchy and its spinoff, Mayans M.C., as well as Jeff Nichols’s The Bikeriders and now Task, have aimed for more true-to-life accountings of biker gangs’ operations that channel the same vicarious pleasures of 1970s movies but set them in some version of reality, reflecting the day-to-day operations of biker gangs and not just paranoid fears about them.

In real life—unlike in most of the bikesploitation movies, which show them riding wild and free—most motorcycle clubs are structured like military organizations, with captains, a rigid leadership structure, and rules about membership, patches, dues, and even the bikes that members are allowed to ride. As Kathy (Jodie Comer) puts it in The Bikeriders, a bunch of hell-raisers who hate rules and regulations banded together to make a group … with a hell of a lot of rules and regulations. And these rules are more strictly—and violently—enforced than the ones in the outside world. “Their idea of ‘provocation’ is dangerously broad, and their biggest problem is that nobody else seems to understand it,” Hunter S. Thompson wrote in his 1965 profile of the Hells Angels. “Even dealing with them personally, on the friendliest terms, you can sense their hair-trigger readiness to retaliate.”

Biker gangs’ cardinal rule—that any wrong done to the club has to be retaliated against, in equal or greater measure—is at the center of Task. The show dramatizes the Dark Hearts’ hair-trigger temper in skirmishes and threats between members, in their attack on Peach Boy’s fiancée and her father, and in the story we hear about what happened to Billy, Robbie’s brother. We find out that Billy was a member who was beaten to death by the Dark Hearts as punishment for breaking one of the club’s rules. We can assume that Robbie—along with whoever his informant is—has been getting his own ill-advised payback against the club by stealing their money and now their drugs. But by getting his little form of revenge, he’s put his own family up against a bigger, more brutal one.

And the Dark Hearts, like any motorcycle club, definitely see themselves as a family, which makes them a fitting villain in Brad Ingelsby’s extended Delaware County universe. Both Mare of Easttown and Task are about networks of families at war with each other and themselves, the rotten, loving heart that crime comes from. It’s loyalty to family that justifies the crimes committed by Robbie in Task and by one character after another in Mare, even when that loyalty ends up putting their families at risk. The Dark Hearts are set up the same way: They’ll do anything for their family, until a brother does something to break the family trust.

The Dark Hearts seem to be set up like a Mafia family, with a leader at the top from whom major decisions flow, captains beneath him, and a network of crime that they manage from above. While the “outlaw” biker gangs often do partake in violence, drug trafficking, weapons dealing, and other crimes, it’s probably uncommon for these crimes to be organized from the top down. Crime might be implicitly allowed by leadership, but it’s more likely that members organize their own drug deals than get orders about them. Hells Angels leader Sonny Barger once said in a club meeting that “what goes on in this room is one hundred percent legal. We don’t talk about illegal things here. Because if you’re doing anything illegal, I don’t want to know about it ’cause it’s not club business.” Former Mongols chapter president Justin DeLoretto has talked about how common undercover agents are in the ranks of motorcycle clubs; it’s probably unlikely that a national Dark Hearts leader like Perry (Jamie McShane) or chapter president Jayson (Sam Keeley) would openly head up an illegal operation since it could risk toppling the whole club—unless they’re just really good at sniffing out and snuffing out informants. (Time will tell!)

It’s not that Task is inaccurate—clubs organized like the Dark Hearts probably do exist, and Anthony Grasso (Fabien Frankel) says himself that they operate more tightly and strategically than any other biker gang he’s seen—but like so many of the movies and stories about biker gangs that came before it, Task taps into our deepest fears and darkest ideas about these groups, not necessarily what they’re really like. That’s natural for a TV series, but it does contribute to the conjoined horror and glamour of the biker gang, going back all the way to the newspaper reports about Hollister, reviews of The Wild One, and movies about demonic riders. Task is just another stop in the feedback loop between what these groups really are and what they look like in pop culture. That’s why the Dark Hearts, or the gangs that fought each other in Waco, can inspire so much fear just by revving their engines. They carry with them loaded imagery suggesting deep loyalty, rebellion, existence somewhere on the fringes of society, and strict, violent rules for belonging and retribution. And they make great villains because they’ve loomed so large, for so long.