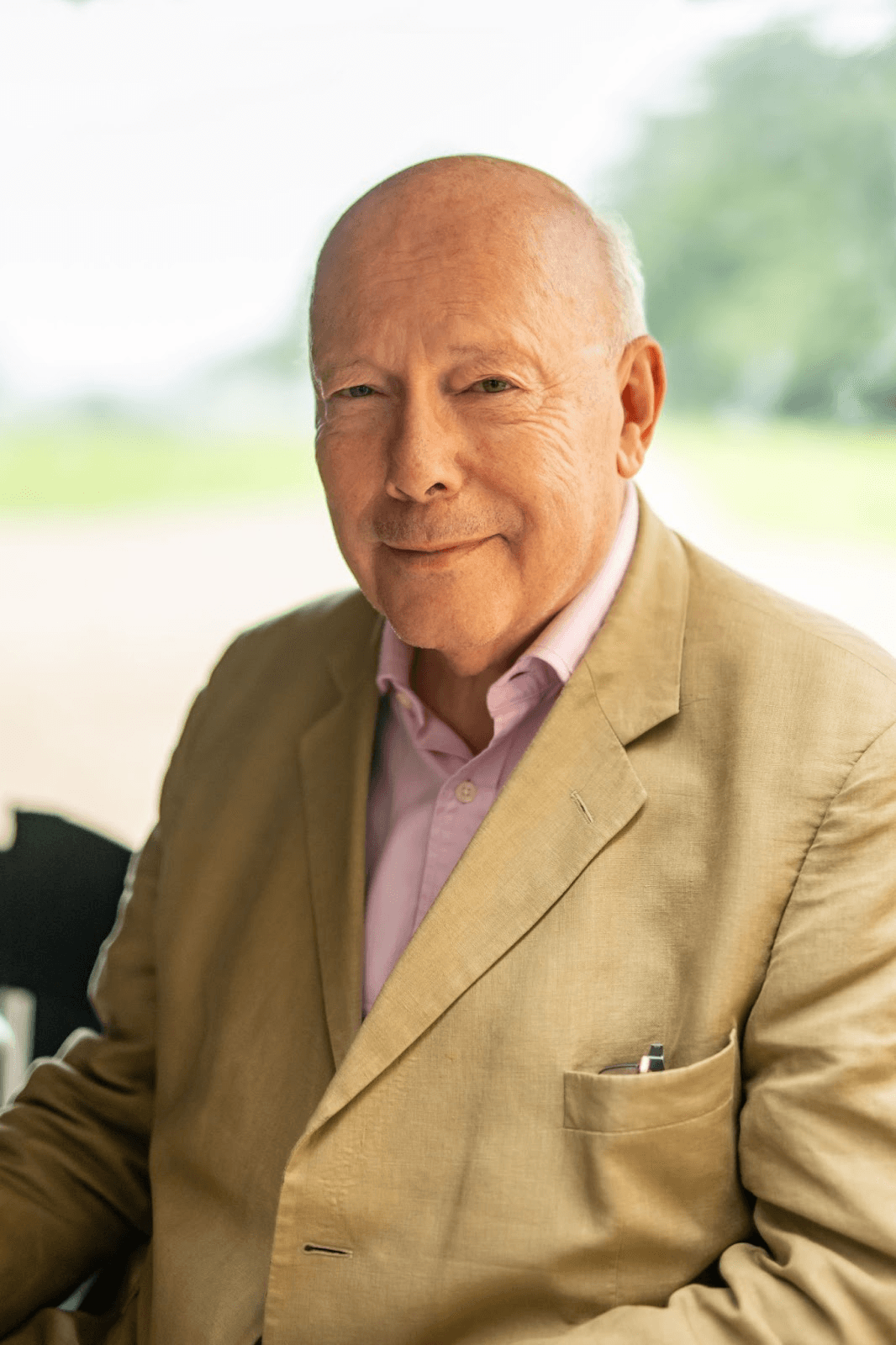

“In many ways, the writers are the real stars of cinema,” hapless footman turned conceited screenwriter Joseph Molesley says in Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale, which opens in theaters on Friday. Downton creator Julian Fellowes, who authored every episode of the series’ six seasons, as well as its theatrical trilogy, surely wouldn’t agree. (Even Mr. Molesley eventually concedes that actors are pretty important.) Yet the world of Downton, which has delighted audiences on both sides of the pond for 15 years, wouldn’t exist without Fellowes, who previously won an Oscar for his Gosford Park screenplay and also created and currently writes HBO’s ongoing The Gilded Age, which has been renewed for a fourth season.

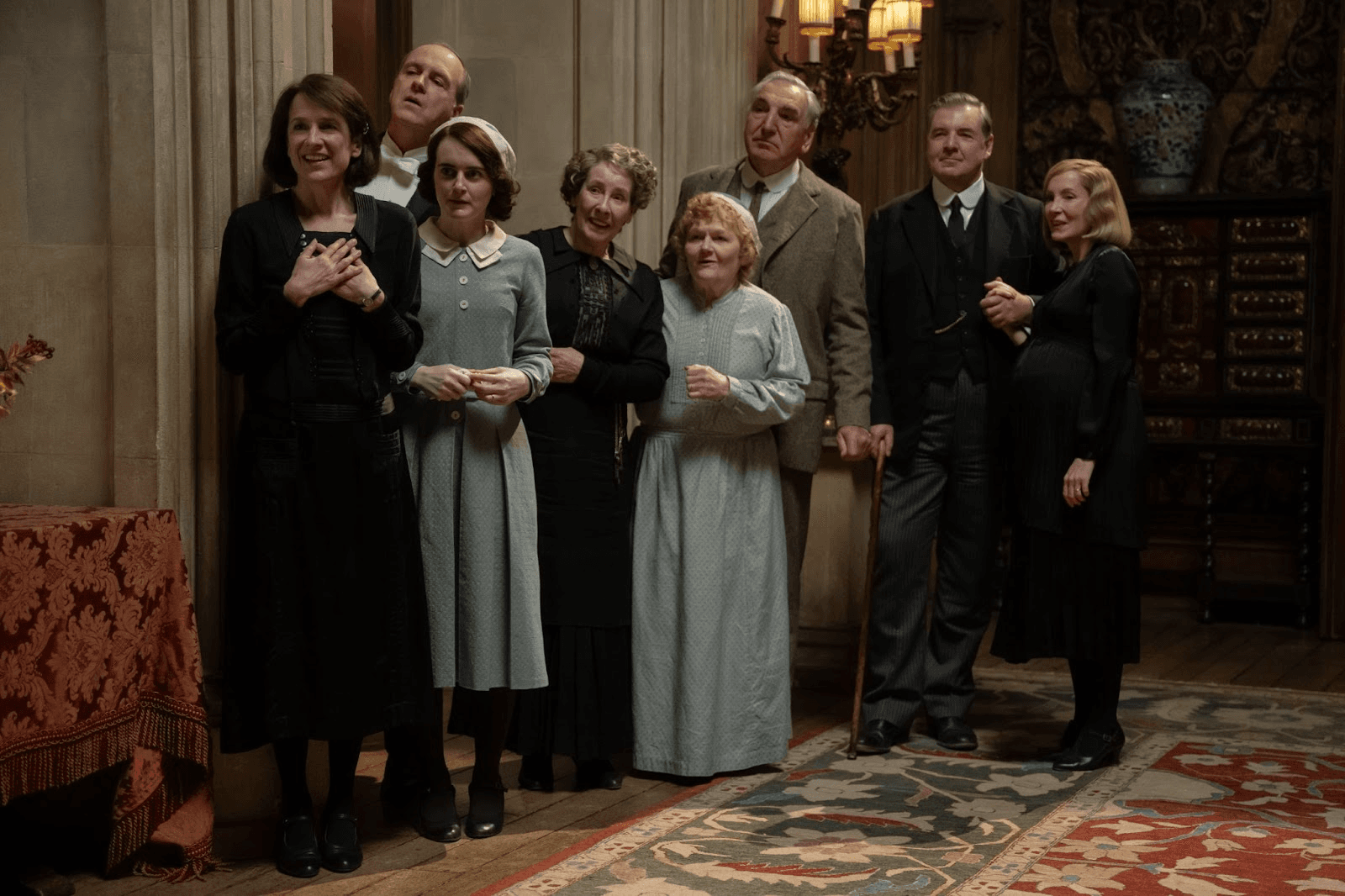

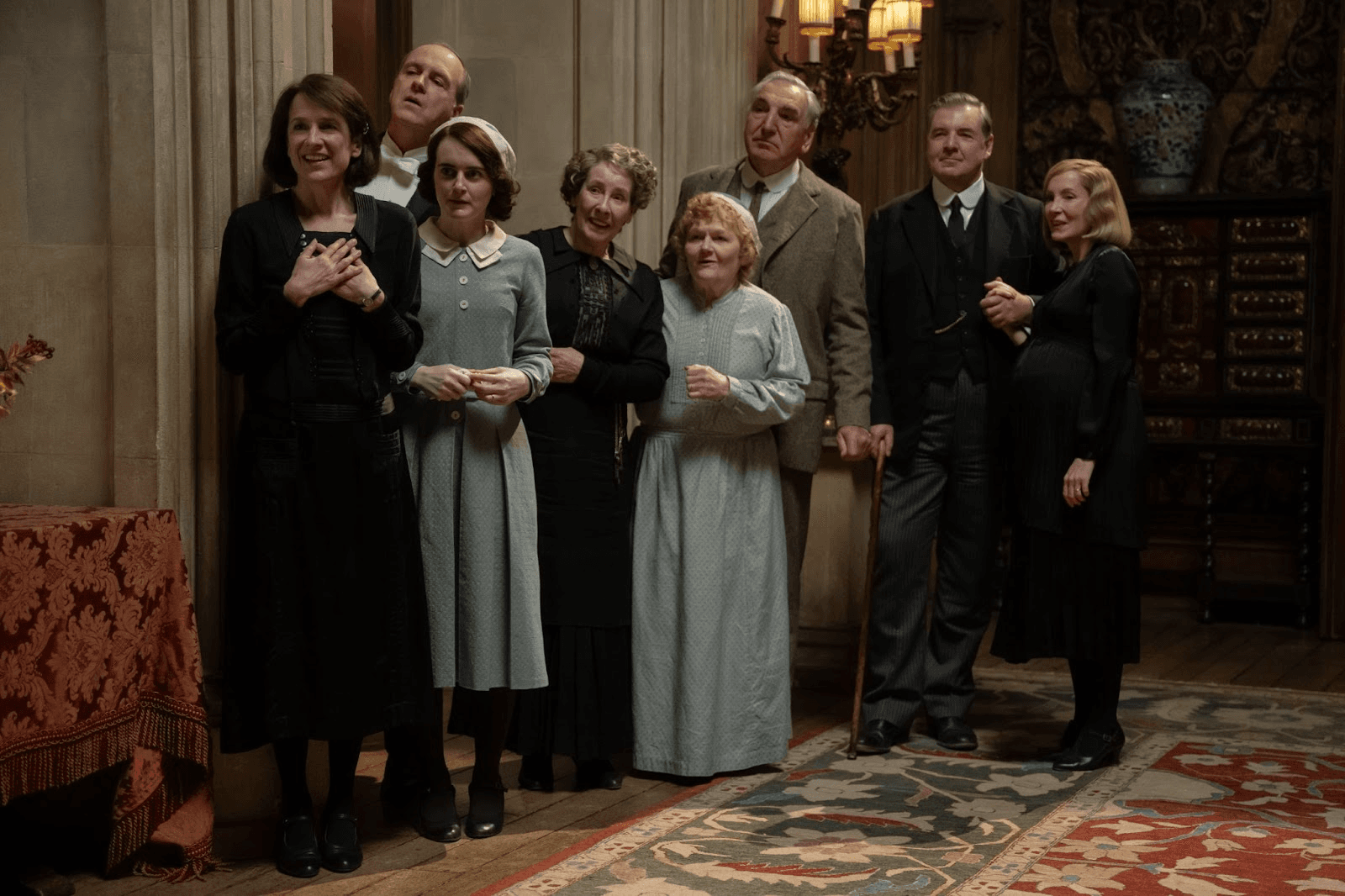

The Grand Finale, directed by Simon Curtis and featuring virtually all of Downton’s familiar faces (save the late, much-missed Maggie Smith), is the sequel to 2022’s A New Era—and, as the title suggests, the end of the Downton saga. The film finds Lady Mary (Michelle Dockery) dealing with divorce and financial misfortune that endanger her own social status and her family’s future. And, as usual, the Crawleys’ story serves as a vehicle for wistful meditations on aging, technological advancements, and social change, as the aristocrats and servants we met in 1912 enter the 1930s—some more reluctantly than others.

The Grand Finale is a fond farewell, full of nostalgic nods to dearly departed characters, the usual dose of upstairs-downstairs drama, and Fellowes’s trademark bons mots and warm, emotional moments. If you’re expecting fireworks, the third and final film may underwhelm, but if you don’t set your sights above a soothing, satisfying finish, then, as Mrs. Carson (née Hughes) confides about her sex life, “It’s terrific fun.” After The Grand Finale, Downton may be dead, but to echo Lady Mary’s pronouncement in the movie, “Long live Downton.”

When Daisy takes over as Downton’s head cook, her retiring mentor, Mrs. Patmore, reflects, “Our lives are lived in chapters, and there’s nothing wrong when one chapter ends and another begins.” As a lengthy chapter in Lord Fellowes’s life ends, I hailed Fellowes (well met) to talk about the conclusion of the franchise, how he imagines the Crawleys’ lives playing out, the differences between Downton and The Gilded Age, and more.

Downton is often described as comforting, or comfort food. Does spending time in this world and with these characters bring comfort to you too?

Well, I think it's a warm show, a kinder show. I also write a series at the moment called The Gilded Age, but The Gilded Age is a much harsher world and a much harsher time. With Downton, we're watching a class whose influence is dying, but nevertheless, it's all quite customary and goes back hundreds of years and all the rest of it, and I think I enjoy that as well. And I think the cast found the right level. It didn't stop us having plots to do with rape and murder and God knows what, we could get into lots of dark stories. But in the end, the world that all these people were peopling was a calm and warm one, and I think I enjoyed that.

Lady Grantham's brother, played by Paul Giamatti, says in the movie, "Sometimes I feel like the past is a more comfortable place than the future." Of course, his present is our past, and our present will be the past for future people. Does that reinforce his sentiment, or undercut it? Maybe that apparent comfort is deceptive, because the past was somebody’s present, and the present will be somebody’s past.

I think the issue really is that, by definition, anything in the past, we have dealt with on some level or other, whereas things in the future, we don't know how to deal with. When the [WGA] writers were striking, which I won't get into, the one thing I didn't really agree with was trying to make all these rules for AI when it's just beginning. The idea that we can circumscribe what happens in the world of AI now is like Queen Elizabeth I trying to pass a law about traffic lights. It's impossible for us to know where it's going to take us, and I think we have to be reasonably philosophical about it. Nevertheless, I think there is something frightening about the unknown, and by definition, the past is known and the future is unknown.

I can't imagine what Lord Grantham would say about chatbots. He's having a hard enough time trying to wrap his head around the concept of an apartment building, where for once he’s the one downstairs. Do characters like Robert speak to you when you aren't actively working on Downton? Will they live on in your mind, even when Downton doesn't?

It's been a very successful show for me, and I've enjoyed them. I think we were very lucky with the cast we got, because that's a big, important part of it. Quite often, you can't get your first choices because they're doing something else. There's no bad feeling, but they can't do it. And in this instance, we seemed to pick a time when almost nothing else was happening, and so we got the first [choice] for almost everyone, and that was very rewarding.

I'm sorry to say goodbye to these characters, really, but I don't want it to sound as if I feel aggrieved. I think I've been very fortunate in the way this series has panned out, and I think we were lucky with our timing, we were lucky with various other elements that meant that it was right for the time that it appeared in. And again, a lot of that is luck. So, yes, is the short answer: I will miss some of the characters, and I hope I keep up with some of the actors. But in the end, I think that the whole thing has been a happy experience.

As bittersweet as it must be to close this chapter in your life, and so many people's lives, I wonder whether it’s a relief to leave behind that logistical element. Wrangling this enormous ensemble cast, clearing (Highclering?) a castle for filming at a time that works for everyone … it must be an entirely different challenge to make what you put on the page come to life.

Happily, I don't have to get into most of that. I send the scripts off, and I'm a producer, so I get involved in casting and the approving of the houses and the locations and so on. But the actual logistics of making it happen, of getting everyone there, of finding the hotel rooms, of getting the meals organized, of getting the makeup organized, no, I don't do any of that, and I take my hat off to those who do.

Even if the actual logistics of the production are, to some extent, other people's problem, they do impact your writing. For instance, so much of Mary's story has been dictated by circumstances beyond your control: Dan Stevens departed the show, and Matthew Goode was unavailable for the last two films, so you've had to craft Mary's love life around those realities. Did those challenges lead to creative decisions you’re pleased with, or do you look back and wonder what might have been?

I'm more pragmatic than that, really. I think if your job is to be a screenwriter of a series, then some things will happen that you're not expecting, and sometimes it's not anyone's fault. Sometimes illness comes in. All sorts of factors come in, and you have to be ready to fit in and change and make it work. And in a way, that's the message of the whole show, to be prepared to accept change and not let it defeat you, and I think that the same is true. I would never have got rid of Dan. I think he was wonderful in the part. They would've had a marriage and they would've had, I don't know, difficulty having children. Mary would've had a terrible disease and they would've had to deal with something.

But it didn't happen because Dan decided to go. And I don't want that to sound critical, because for actors there's no rulebook, no one's telling them what to do. They have to follow their gut. And he was offered a show on Broadway, he was offered a movie, he was offered various other things, and he thought, this is my time, this is the right time to leave this and go. We didn't part on a quarrel or anything like that, and I'm always very pleased to see Dan when I do. But of course, it meant a total restructure. But then you think, well, we've got to do this, that's the unalterable bit, and so let's see how we can make it work for us.

And what I realized is that by killing [Matthew], it meant then having a six-month gap, because I didn't want to do too much of the boo-hoo, and then we come back and Mary's beginning to start her life off again, and so you've got all these possibilities of her finding a new partner and so on and so forth and you've got all sorts of things that you could do that you couldn't have done if Dan was still there. So I think that is part of the job, to be honest. I think every job has its difficulties, but one of them is that if you are writing an ongoing series, you just have to be ready for changes that you weren't looking for and try to keep good humor about it.

Now Mary's second marriage has come to an end, not by death but by divorce. I'm a Gilded Age watcher as well, and I can't help but notice that you’ve broken down societal resistance to divorce on both sides of the Atlantic this year.

But it came sooner in America.

Yes, almost half a century of separation.

It really came from Alva Vanderbilt, who married Oliver Belmont in the 1890s and was horrified to find she was no longer invited to various things. And so she married her luckless daughter, Consuelo, off to the Duke of Marlborough, who was horrid. Nevertheless, that achieved what Alva needed from it and got her back into society, which made America really about 40 years ahead of England and Europe in accepting divorce. Actually, England was ahead of countries like the Catholic countries—Italy and France and so on—they were behind us.

With these divorce plot lines coinciding, I wonder whether you see The Grand Finale and Season 3 of The Gilded Age as being in conversation. Was that intentional? Did you have divorce and the social opprobrium surrounding it on the brain while you were working on these projects?

I was very interested in divorce, because I think the divorce and the acceptance of divorce was a casting-off of the Victorian idea that you make your choices and, that's it, and you're stuck with them until you die—and the idea that you can remake your life and reshape it on different lines is essentially a modern one. And I think it was beginning in America, as I say, in the 1890s, but in England, really, it was the beginning of the ’50s that it started to become quite normal for people to be divorced.

It did always strike me as a very interesting element that we had to get used to. And I do think there is some fun in seeing the two societies side-by-side, but The Gilded Age is a much darker place than Downton. Downton is essentially warm and cuddly and you watch it with some nice mulled wine and everything's lovely. But I think the world of The Gilded Age, of Jay Gould, the people like that, of “Commodore” Vanderbilt and so on, these were tougher people and a tougher world.

Along those lines, it seems to me that in the upstairs-downstairs divide, Downton’s screen time has been skewed more toward the downstairs than The Gilded Age, recent developments surrounding Jack and his clock notwithstanding. I know more about the personal lives and inner lives of Downton's downstairs staff than I do The Gilded Age's, and I wonder why that is.

I think that the reason for that is that ... well, there are several reasons, but one of them is that, on the whole, the servants in America weren't children of tenant farmers for the last 200 years, they were immigrants getting off the boat, getting the first job they could get that would feed them, and they came from Germany and Ireland and so on and so forth. And many of them came with very different ambitions, and the plan was to get going in this land of opportunity that had far more openings than Europe, all of which is true.

And so, to make a storyline like Jack's work in Downton … of course, if I said on television, “Oh, there were no servants who became millionaires,” 15 people would immediately write in with the names of their great-grandfather who invented a new kind of fork. But basically, on the whole, people born into the working class in England were likely to stay in it—not inevitably and not completely, but likely. Whereas the American servant class is much more mobile, and if you look at the early working years of the immigrants who came and did very well and became bankers or whatever …

We filmed at [the Phipps family’s] garden just outside of New York. And they became bankers. They started as cobblers and they arrived from Germany as cobblers, but of course, they didn't want to stay cobblers, which is why they'd gone to America. And so, they soon got into finance and then they had their own bank, and then before you could say Jack Robinson, they were multimillionaires and leaders of Gilded Age society, and that was essentially an American story much more than a European one, and I think that was all part of it.

I think also, in The Gilded Age, we have the other rivalry, which is old money and new money. And of course, in America, new money wins, mainly because there's more of it. And so that battle is also being fought out. There's no equivalent to that in Downton of a rival estate bought by some businessman; we just didn't go down that road. And so, in a sense, we've got the two groups, but they both get on. There's no hostility between the groups, and so it's a different dynamic.

You're not making a multiverse or an interconnected cinematic universe, but there seems to be such an appetite for crossovers between Downton and The Gilded Age. Even though these are separate worlds on separate continents and in separate centuries, you’re often asked, “When will they mingle?” Does that surprise you?

I don't know that it surprises me, but I don't know the answer, either, and so we'll have to see.

Each show has some characters who could be analogues to characters on the other; maybe Aunt Agnes is The Gilded Age’s answer to Downton’s Dowager Countess. But are there particular characters you sometimes wish you could transplant from one to the other? Not an actual crossover, but a character you’d be interested in seeing operate as a fish out of water in the other series’ milieu.

I think if I was doing another version of Downton or coming back to the household at a more modern period, I would like to see some new money which started to operate in Europe, more after the war. I don't think we exhausted that at all in Downton. They didn't on the whole get involved with new money. Most of the people they married or stayed with or shopped with or did whatever they did with were members of their own world. Whereas, if I was coming back to it after the war, I think I would be more inclined to bring in characters from a very different world.

Speaking of different worlds: Because of their settings, neither Downton nor The Gilded Age really lent themselves to great diversity in the demographic makeups of their characters and casts. But you've moved in that direction in some ways, whether with Barrow on Downton or Peggy on The Gilded Age. Was that a goal of yours, and has it been a challenge as a writer?

I was, in a way, looking for ways to make it quite clear that The Gilded Age was not set in England and that it was a different place and a different country. I chanced to read a book called Black Gotham about the second half of the 19th century in New York and the Brooklyn-based Black bourgeoisie that flourished there. And as I was reading it, that was the answer I'd been looking for, because I could bring these people in without falsifying history, without making a statement that wasn't true, and yet they could all be part of the general picture. When we started, [a lot of people] said, “Oh, there was no such thing as a Black middle class.” And happily, the historians came down on our side and said, “Yes, there was,” and that was that. And I feel that having Peggy's story in it makes it seem very American and not English, and that was what I wanted.

Happily, The Gilded Age is continuing, so we’ll have some Fellowes to look forward to. It would've been a blow to lose both of your series in the same year. Did you choose the title The Grand Finale to draw a line in the sand and leave no doubt that this is the end for Downton? Because as satisfying as the ending is, it needn't be a definitive one. The story could continue.

I think if we did continue, it would be in a different time, with different actors. Everything would be different. And I think we all knew that this was going to be the end of the original conception of Downton Abbey, the original cast, the original all of it, and I think that we chose The Grand Finale to make that clear. In a way, we could have meant that with [A New Era], but we didn't, and there was another film. But this time, these people will not be seen again. I hope they will be seen again at my dining table. But this period of writing and so on for all of us has come to, I hope a good end, I think a good end, but it has come to an end, yes.

You reference Coward's Cavalcade in the film. Is it a coincidence that the movie is set the same year that Cavalcade concludes? You don’t end your story on an ominous note, but it’s an ominous era. The Depression rears its head, and we know another war is on the way. So we're largely leaving these characters in a happy place, but clouds are looming.

There are trials to come, and I hope we leave them in a place where we are reasonably confident that they're going to be able to deal with those trials. Of course, George will fight in the war and we have no way of knowing if he'll get through it, and that's just how it is. But I think that Mary and the others are prepared for the different world of the 1930s that will eventually take them through the Second World War.

Cavalcade was put on very soon after Bittersweet, which we start with. But I don't remember being particularly struck with that. I do remember that we were interested in Noel Coward being emblematic of the years between the wars. In every period, there's the odd player who seems to represent that time, whether it's Marilyn Monroe or whatever, and Coward was the voice of England between the wars—that strange, quite short, 20-year period between the wars—and he embodied it without anger and without rage. He embodied it with wit and good humor and generosity. But he was very different from a Victorian stage star. He wasn't a Victorian at all. And I think that that was the point we were making with Coward, that this was a new time and a new age and we were going to leave them living out their lives in a different time.

Even though this is the end of Downton’s story on-screen, have you mapped out the rest of these characters’ lives? Do you know what would happen to George, to Mary, and to Downton, even if you won’t divulge their fates?

Well, I hope that the Crawleys stay on at Downton and they are one of the families that gets through. But of course, that was very dependent, A) on how much capital they had, and B) on the kind of advice and financial planning they were taking advantage of. Many families went under because they simply didn't consider the issues from a grown-up point of view, and indeed, we're often quite critical of families that did. The Duke of Bedford got it very much in the neck for being a modern and for saying, "The life that my great-grandfather lived in this house is not available to me anymore, I can't live like that anymore." And he would get very bad press for that, but he was right. And so I hope that Mary is the person to take them through to a realistic place. But as to whether or not that happens, I don't think I can claim too much omniscience. I think there is a moment where you have to back off and let the audience decide.

How have you managed to make these characters so endearing and relatable to audiences who might be inclined to say, “I see nothing of myself in these people's lives; they're classist, they're posh, they're privileged, they're prejudiced”?

I think that we live in a world which constantly refers to things that make us different, and all our politicians try to get votes by pointing out the differences and how they're going to represent this group and so on and so forth. I think that for real people, what we have in common is far more than what we have not in common.

We made it clear that these people may dress in haute couture and they may live in a great house and all the rest of it, but what they're actually dealing with on a daily basis, in their failed marriages or trying to bring up their children or being in love with the wrong people or whatever, is completely relatable to more or less everyone. And I think that we tried to make the point that the upstairs characters and the downstairs characters were all going through their own problems, they all had their stuff that they had to deal with. And I believe that of life: that on the whole, what unites us is far greater than what divides us, and I just wish there were more politicians who agreed with me.

Do you ever envy P. G. Wodehouse, who could keep telling stories about the characters he created for 60 years, and they could remain frozen in time because he didn’t have to worry about actors aging or being unavailable? In print, you could preserve Downton Abbey in amber and return to it whenever you’d like.

On the whole, although I'm an admirer of P.G. Wodehouse and good luck to him, what I feel is that if you've chosen one of these essentially mad careers that keep your parents awake at night when you're young, because all they see ahead for you is a life of starvation, and it works and you're one of the lucky ones and you're allowed to get through, then that's enough. I think to start qualifying your success and demanding different elements of it, you want to say to them, “Just pipe down and be glad with what you've got,” and I'm glad with what I've got.

When Robert tells Cora, “We've done our duty, we've given half our life to Downton,” and then, with his hand, plants a kiss on the castle, is that you speaking and acting through him as you lay down your pen?

It was my wife, actually, who wanted him to plant the kiss on the house. I've known people who have given their lives to these houses and these estates and everything. And of course, there's moments you think, if they just sold everything and went and lived in New York and bought a nice house in the sun somewhere, they could live a wonderful life and never do any work at all and go to the club for lunch. That's not what they chose—they chose to give their lives to these places to keep them going. Personally, there are some, I'm sure, who would feel that's the wrong choice. But for me, it was a noble choice, and I admire Robert Grantham because I admire the real-life versions of him that I've known.

Robert also asks Bates, “Do you ever think of where it all began?” Some of your characters have come quite a long way: Lady Edith has come into her own, and Barrow is living his best life in Hollywood. I'm also glad you got to give Maggie Smith a fitting send-off in the last film, and constructed this one as an ode to her. Is there another character whose trajectory you regard with special satisfaction?

I think I feel that about all of them, really. On the whole, they've all made choices that have led to their best life. And of course, in real life, there probably would be about at least a third of them who had made choices that led to their worst life. But that isn't where Downton is, really, certainly not when we're saying goodbye to them all. And although some of them will go on living much the same lives that we've seen them live, I don't want any of them to be unhappy. And so, on the whole, they're all happy.

This interview has been edited and condensed.