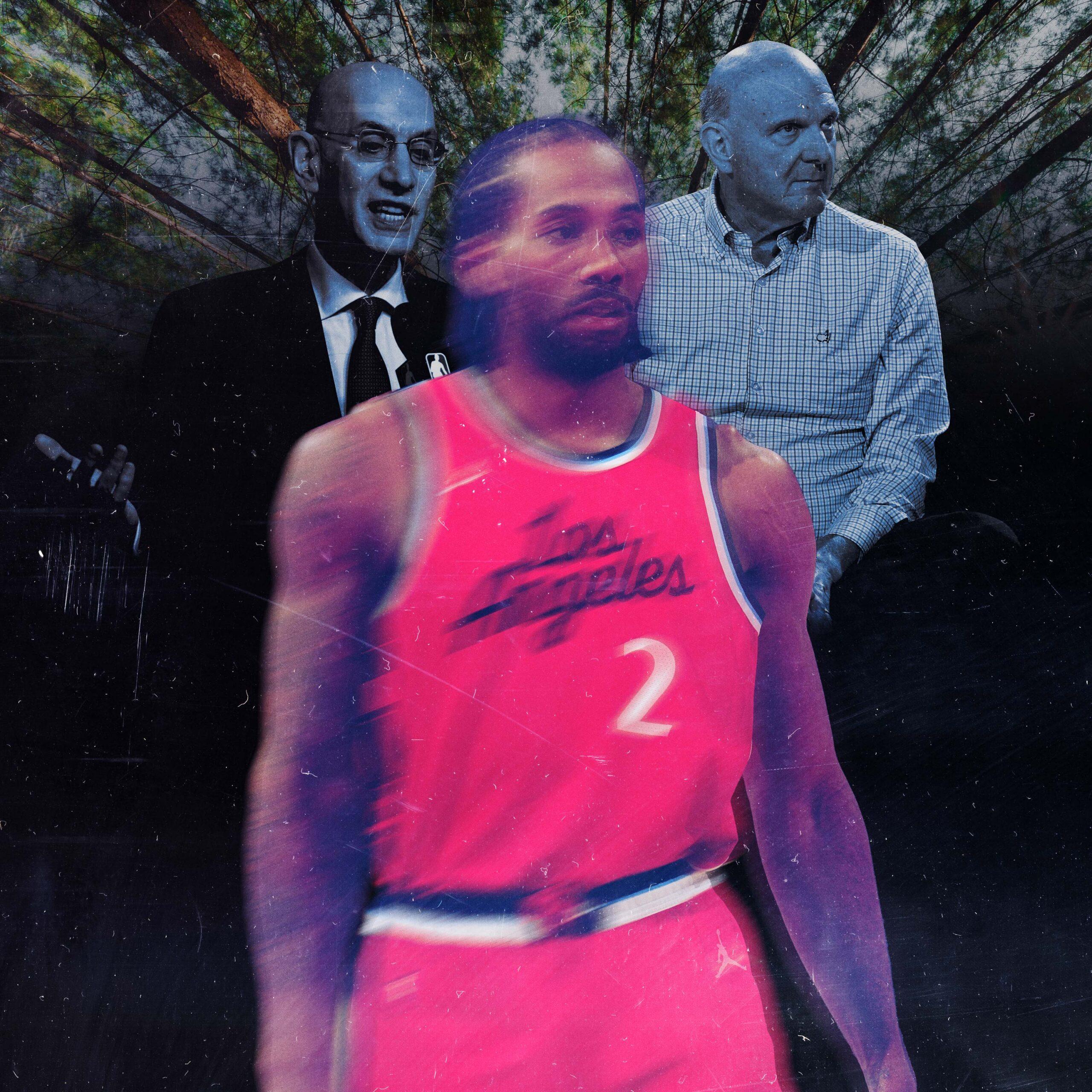

What We’ve Learned About the Kawhi Leonard Situation—and What We Haven’t

The NBA’s investigation of the Los Angeles Clippers will almost certainly take center stage at the board of governors meeting this week. We canvassed sources around the league to gauge what’s next for Kawhi, Steve Ballmer, Adam Silver, and more.

There were two universal reactions to last week’s explosive reporting that the Los Angeles Clippers had enlisted a team sponsor to pay Kawhi Leonard tens of millions of dollars, purportedly for the express purpose of circumventing the NBA’s salary cap.

Reaction no. 1: What the bleep?!

Reaction no. 2: How bleeped are the Clippers?!

Even after several days of discussion, denials, and follow-up stories, the shock around the league remains fresh and the details stunning. According to veteran journalist Pablo Torre’s reporting, in 2021 Clippers owner Steve Ballmer invested $50 million in a start-up company called Aspiration—and Aspiration in turn signed Leonard to a $28 million “no-show” endorsement deal. Per Torre, Leonard would be paid even if he never did anything to promote the company, which has since filed for bankruptcy. An unnamed Aspiration employee told Torre that this was actually all a scheme to skirt the NBA salary cap and provide Leonard with compensation beyond what was allocated by his standard player contract.

If true, it would be the biggest (in dollars) and most audacious (in sheer chutzpah) case of salary cap circumvention in NBA history—and one of the league’s biggest scandals of the 21st century.

The Clippers immediately denied any wrongdoing in a pair of written statements, and Ballmer further pushed back on the report in an on-camera interview with ESPN. The NBA announced that it would be launching an investigation.

The matter is certain to take center stage on Tuesday, when the NBA’s board of governors holds its regular September meeting in New York, and again on Wednesday, when commissioner Adam Silver holds his regular post-meeting press conference.

The NBA has retained the New York law firm Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz to conduct the investigation, according to The Athletic. It’s the same firm the NBA used to investigate then–Clippers owner Donald Sterling (for accusations of racism) in 2014 and then–Phoenix Suns owner Robert Sarver (for accusations of racism and misogyny) in 2021. Both men were eventually pressured to sell their franchises.

So, just how bleeped are the Clippers and Ballmer? It’s way too soon to know. We repeat: way, way, way too soon. The NBA under Silver tends to be very methodical about these things. It will act on what it can reasonably prove, not on what merely looks bad. If it turns out that the Clippers did indeed instigate this whole saga, the penalties could be severe: forfeited draft picks, a suspension for Ballmer and team executives, a hefty fine, and perhaps even a voiding of Leonard’s contract. It’s also possible that the Clippers could evade sanctions entirely, depending on what the NBA does or doesn’t find. And Silver, a lawyer by training and cautious by nature, isn’t likely to reveal much at Wednesday’s presser.

In the meantime, we’ll attempt to unpack it all here, FAQ style, based on our own reporting and conversations with several sources around the league, who were granted anonymity for their candor.

So a billionaire NBA owner might have gotten a team sponsor to pay a few million more to a millionaire NBA superstar. What’s the big deal?

It’s a big deal because the NBA has a salary cap (projected at $154.6 million for the 2025-26 season) and a 676-page collective bargaining agreement that governs everything to do with player salaries and team payrolls. These are the rules that every franchise, as well as the players union, agreed to, for the sake of competitive balance and, more broadly, a sense of order.

Willfully circumventing the salary cap is considered a cardinal sin. It’s cheating. It undermines the entire system and, if unchecked, could threaten the stability of the league. Franchise values—which have skyrocketed over the past 10 years—are based in part on the cost certainty that the salary cap provides. If the cap is rendered meaningless, “it fucks franchise values,” said one team executive. “If the CBA doesn’t matter, that’s bad for all owners. … The integrity of the league is at stake.”

Translation: Expect Silver and the NBA owners to take this case very seriously.

Oh, come on. This sort of thing happens all the time, doesn’t it?

No. Not all the time, and certainly not at this scale, according to every team executive and league insider we’ve spoken to since the story dropped.

Teams sometimes connect players with team sponsors or local businesses to help facilitate an individual endorsement deal—a practice that is indeed common and fully within the rules. Stephen Curry, for instance, does commercials for Rakuten, which has a sponsorship deal with the Golden State Warriors. The HEB supermarket chain, a longtime sponsor of the San Antonio Spurs, has long employed Spurs players to star in its cheeky TV commercials.

But these sorts of deals generally pay in the hundreds of thousands or, at most, “the low six figures,” per multiple sources, and they require the players to actively promote the brand—via commercials, appearances, or social media posts.

According to Torre’s reporting, however, Leonard’s deal with Aspiration did not require him to do anything—and Leonard, by all appearances, indeed did nothing. Yet Aspiration agreed to pay him $28 million, of which it still owes $7 million, per the bankruptcy filing. Leonard also had a side deal with the company providing an additional $20 million in (now worthless) stock, according to the Boston Sports Journal. Also of note: The entire deal would be void if Leonard changed teams, according to documents reviewed by Torre.

None of this is normal, according to people around the league. “It reeks,” said a former player who has also worked in a variety of front office roles. The dollar figures alone are “extreme,” said another former team executive, who added that the “no-show” element was “a huge red flag” and “smells the most in this whole thing.”

No one we spoke to said that they had ever witnessed or even heard whispers of anything quite like this during their years working in the NBA. This is a cynical league in which a number of below-market contracts for star players have raised suspicions over the past two decades. But an assertion that “everyone is doing it” was emphatically dismissed.

“Everyone is doing it?!” said one current team executive, adding, with a laugh, “No. Everyone is not funneling $48 million under the table through sham sponsorships.”

OK, but teams are skirting the cap rules, aren’t they? You don’t really expect me to believe that everyone is dutifully following the rules.

Yes, some relatively modest cap circumvention does happen.

A team might ask a player’s agent to exercise an early-termination option—or forgo the opt-out—with verbal promises of a future payday. A player might get access to the owner’s private jet or get a free car from a local dealership that does business with the franchise.

Here’s how it worked in one recent instance, as relayed by a team source: A team needed to come up with an extra $150,000 to persuade a free agent to sign. So the GM arranged a $150,000 deal between the player and a local business, requiring the player to make a certain number of promotional appearances. (The team got the player.)

So yes, if a team needs a sweetener to convince a star player to sign, it can usually create one. Just nothing that even remotely resembles the scale of Leonard’s deal.

“There’s sort of honor among thieves, an inbounds area that you can do things,” said a longtime team executive. “Everyone sort of knows what everyone does. I don’t think anyone has ever tried, to my knowledge, to give a player $24 million to $48 million under the table.”

So the NBA has to hammer the Clippers, right?

Yes. Probably? Maybe. But, well, not necessarily.

The case laid out by Torre on his podcast, Pablo Torre Finds Out, is indeed compelling. Certain details—like the report that the deal would be void if Leonard left the Clippers—sound downright damning. As does the quote from the unnamed former Aspiration employee who said that the deal was expressly conceived “to circumvent the salary cap.”

The initial reaction around the league to that report? “They’re fucked,” said one team executive. “That’s what most people think.”

But the league, assuming it finds the same employee, could consider the statement about cap circumvention to be mere hearsay, absent some physical proof. To wit: How does the employee know this? Who told them? And how does that person know that it’s true?

The key to proving cap circumvention would be a request from Ballmer (or someone else representing the Clippers) directing Aspiration to make the deal with Leonard. And as of now, it’s unclear whether any concrete proof—a memo, an email, a text—exists.

Would an über-wealthy NBA owner really be foolish enough to leave a paper trail?

Well, let me introduce you to Glen Taylor, the now-former controlling owner of the Minnesota Timberwolves. In 1999, the Timberwolves signed forward Joe Smith to a free agent deal that was wildly below his market value. A year later, it came to light that the Wolves had agreed—in writing—to give Smith a far more lucrative contract, up to $86 million, once he had earned his “Bird” rights with the team.

NBA rules expressly prohibit any promises (i.e., “wink-wink” deals) of future earnings.

It was, at the time, the most blatant case of cap circumvention since the league had adopted a salary cap in 1984. The punishment was severe. Commissioner David Stern docked the Wolves five first-round picks (two were later reinstated), suspended Taylor and vice president of basketball operations Kevin McHale for the rest of the 1999-2000 season, and voided Smith’s contract.

But that case came to light only because of a lawsuit involving Smith’s agent. The prohibited contract was unearthed during the discovery phase. The league didn’t even have to search for a so-called smoking gun—it was right there in court records.

And that, presumably, is what the NBA and the Wachtell Lipton lawyers are searching for. Where Torre’s investigative report was based primarily on court records and interviews, the NBA can go much further. It can demand emails and texts from the Clippers, which is where any presumed smoking gun would be found. The league also can, and will, interview Clippers executives and any employees who could have knowledge of the matter.

The Clippers' defense rests upon the assertion that they had no involvement in the contract between Aspiration and Leonard. The burden of proof would seem to be on the NBA to demonstrate the Clippers’ participation in the deal, not on the Clippers to prove their innocence. As we mentioned earlier, Silver is a lawyer by training. He has generally erred on the conservative side in prior investigations, acting only on the proof in front of him.

If there’s no smoking gun, will the whole thing just go away?

This might be the biggest question of all. What will Silver do if there’s no concrete evidence? And if the Clippers aren’t sanctioned, how would rivals react? Would everyone be rushing to line up shady deals for star players? Would the NBA turn into the Wild, Wild West? Would anyone have any faith in the system at all?

Even without hard evidence, people around the league are having a hard time buying the Clippers’ denials.

As one team exec said, it’s “stretching credulity” to believe that Aspiration acted on its own, that a start-up would hand a player tens of millions without requiring anything in return or go to such great lengths unless the team had asked for it.

And hard evidence might not technically be required for the league to act. As The Ringer’s Zach Lowe noted on his podcast, the CBA states, in Article XIII, that cap circumvention “may be proven by direct or circumstantial evidence, including, but not limited to, evidence that a player contract … cannot rationally be explained in the absence of conduct violative of [salary cap rules].”

Translation: The NBA might not need a smoking gun. But given Silver’s record and temperament, he would surely prefer one before hammering the Clippers and Ballmer. Without direct evidence, the league could open itself up to a lawsuit. And if the NBA voided Leonard’s current contract (a three-year, $152 million deal), as it did with Smith, Leonard could challenge the ruling via the players association and the courts.

“Can they prove what Steve Ballmer knew or did not know about Aspiration?” a former team executive said. “Was it direct, was it indirect? Did he know? To me, that’s going to be the crux of the issue. Even if they suspect he knew it, can they prove it? Is there any kind of paper trail? If that’s the case, they need to come down hard.”

“It’s a huge test” of Silver, the same former executive said. “If even a fraction of it is true, it’s a fascinating test.”