The Los Angeles Clippers were up against a new opponent. Last summer, just as the NBA’s new collective bargaining agreement was set to go into full effect, the team faced a pair of massive decisions. Both Paul George and James Harden were unrestricted free agents, and with the team set to open up its sparkling new arena in Inglewood, expectations for the Clippers were sky high.

By now, you’ve heard a lot about the so-called second apron, a new tax threshold that includes the harshest overspending penalties for teams in NBA history. Massive luxury tax bills are nothing new, but for the first time ever, the current CBA penalties punish big spenders by severely constraining their team-building tools. The second apron is essentially a poison pill provision so toxic that many teams now view the threshold as an effective hard cap that has already significantly changed how owners and front offices value players and contracts in the best basketball league in the world.

Instead of offering both George and Harden long-term max extensions, which used to be a near given, the Clippers offered what I like to call “situationship contracts”—deals that fall somewhere between a fling and a committed relationship, with high average annual salaries but fewer seasons than stars are accustomed to getting. Harden re-signed with the Clippers for two years and $70 million. George was offered a similar deal, as he recounted on a later episode of his podcast, but he instead found a team that was willing to give him everything, signing for a much juicier four years and $212 million with the Philadelphia 76ers.

Steve Ballmer, the richest owner in the NBA, had just bent the knee to the second apron. The game had changed. With George out of the picture, the Clippers signed role players like Derrick Jones Jr. and Nicolas Batum to bargain deals that the vets overdelivered on.

Meanwhile in Philadelphia, Daryl Morey used max slots to lock in a new Big Three of his own. Not only did he ink George, but in July he gave Tyrese Maxey a five-year, $204 million max deal and in September handed a three-year extension worth over $190 million to the oft-injured Joel Embiid. The latter deal also includes a massive fourth-year player option that would add another $67 million for the 2028-29 campaign. While paying an ascendant player like Maxey remains smart business, the new rules make long-term deals with aging stars more risky than ever; teams with big money locked into underperforming superstars simply won’t be able to compete on the floor or in the market.

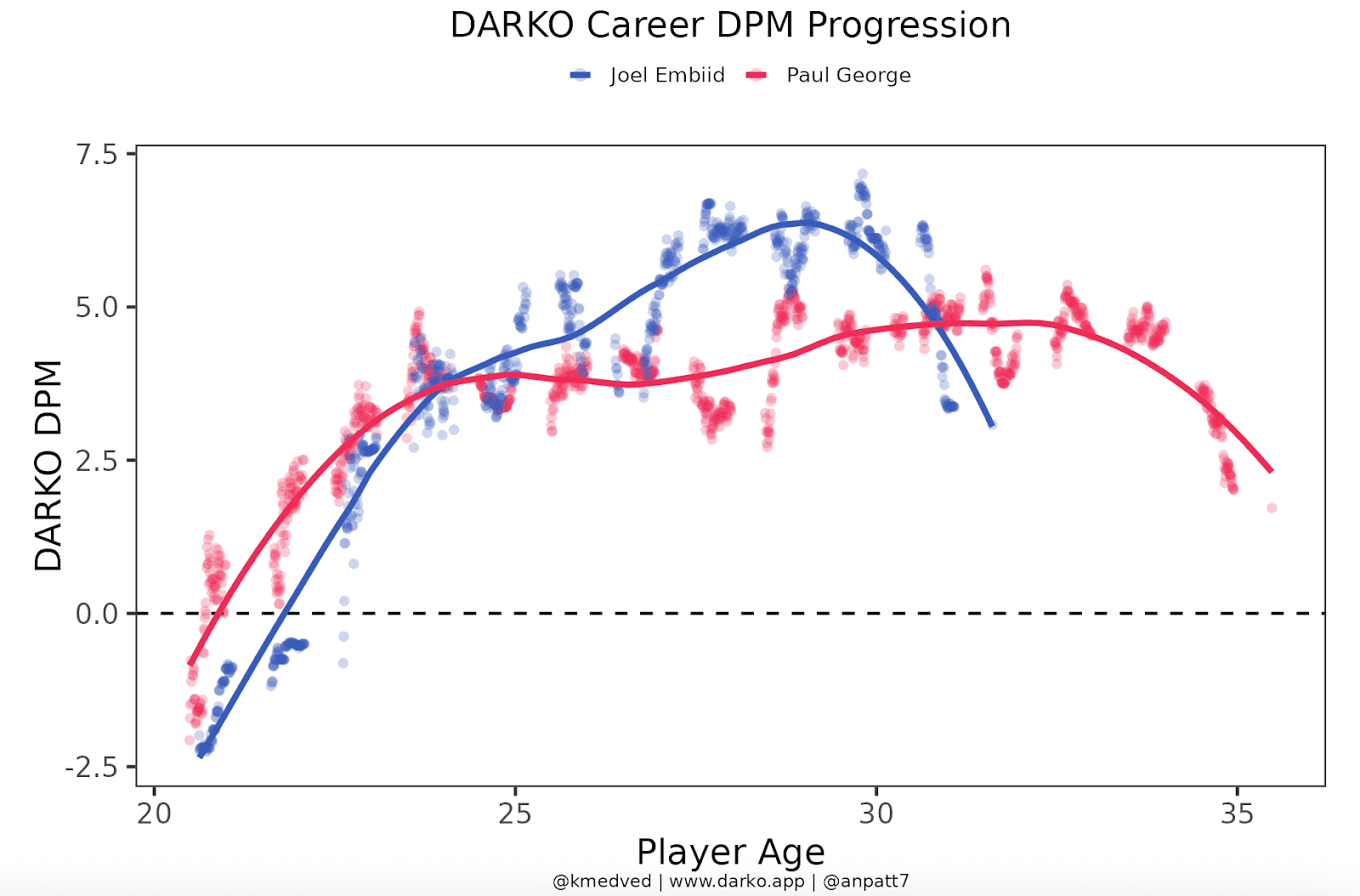

This chart shows the career daily-plus-minus trajectories of both Embiid and George. If current trends continue, the Sixers are fully committed to deals that pay for past performance, a cardinal sin in front offices across sports. George played in only 41 games last season, Embiid managed just 19, and the team completely crumbled to a Process-esque 24-58 record. Now the Sixers are stuck with two massive contracts they probably wish they hadn’t given out, while the Clippers look savvy. The George saga captures how the league is changing in the time of the second apron.

So what does the Sixers’ tale mean for the NBA’s future? Three things are happening at once.

First, teams are more afraid of tax thresholds than ever before. Even the league’s wealthiest owners are now “ducking the tax” in ways that they weren’t just a few years ago. While Ballmer and the Clippers provide the best example, they are by no means alone. The Boston Celtics chopping up their championship roster and selling it for parts is another obvious data point here. Only one team in the entire league, the Cleveland Cavaliers, is above the second apron threshold. Technically, the NBA still does not have a “hard cap,” but when 97 percent of its teams are acting like it does, naturally the market for the league’s top talent has changed.

Second, as more star players like George and Harden are playing deep into their 30s, and in some cases like LeBron James their 40s, many of the league’s most damaging contracts right now involve a team guaranteeing long-term money for a player past his prime. In recent years there have been embarrassing cautionary tales that cost ownership groups a bunch of cash. In the second-apron era, these deals are handcuffs; the biggest Shams bombs of this summer weren’t about superstars switching teams, they were about the Milwaukee Bucks and Phoenix Suns throwing hundreds of millions of dollars in the trash to waive and stretch Damian Lillard’s and Bradley Beal’s max deals, respectively—unprecedented maneuvers that prove that conventional front-office wisdom has changed.

Third, the rise of analytics has changed how owners and executives evaluate their investments. Like it or not, aging curves like the ones above have tanked the market for older stars. These kinds of tools offer a sober glimpse into how age affects performance in the NBA. The key takeaway: The modern league is a young man’s game. Twelve of the league’s 15 All-NBA performers last season are 31 or younger. Giving an old fella a long-term max is the new midrange jumper. Ironically, it’s Daryl Morey’s cap sheet that looks like DeMar DeRozan’s shot chart at this point.

The combined effect is the rise of the NBA situationship for many of the league’s big names. Two- and three-year contracts for stars are surging in popularity. Just this summer, Kyrie Irving, Fred VanVleet, James Harden, and Julius Randle signed relatively short-term “situationship” deals. Even LeBron, the face of the league, finds himself in a situationship, and let’s be honest: It’s awkward as hell. Both sides have a wandering eye.

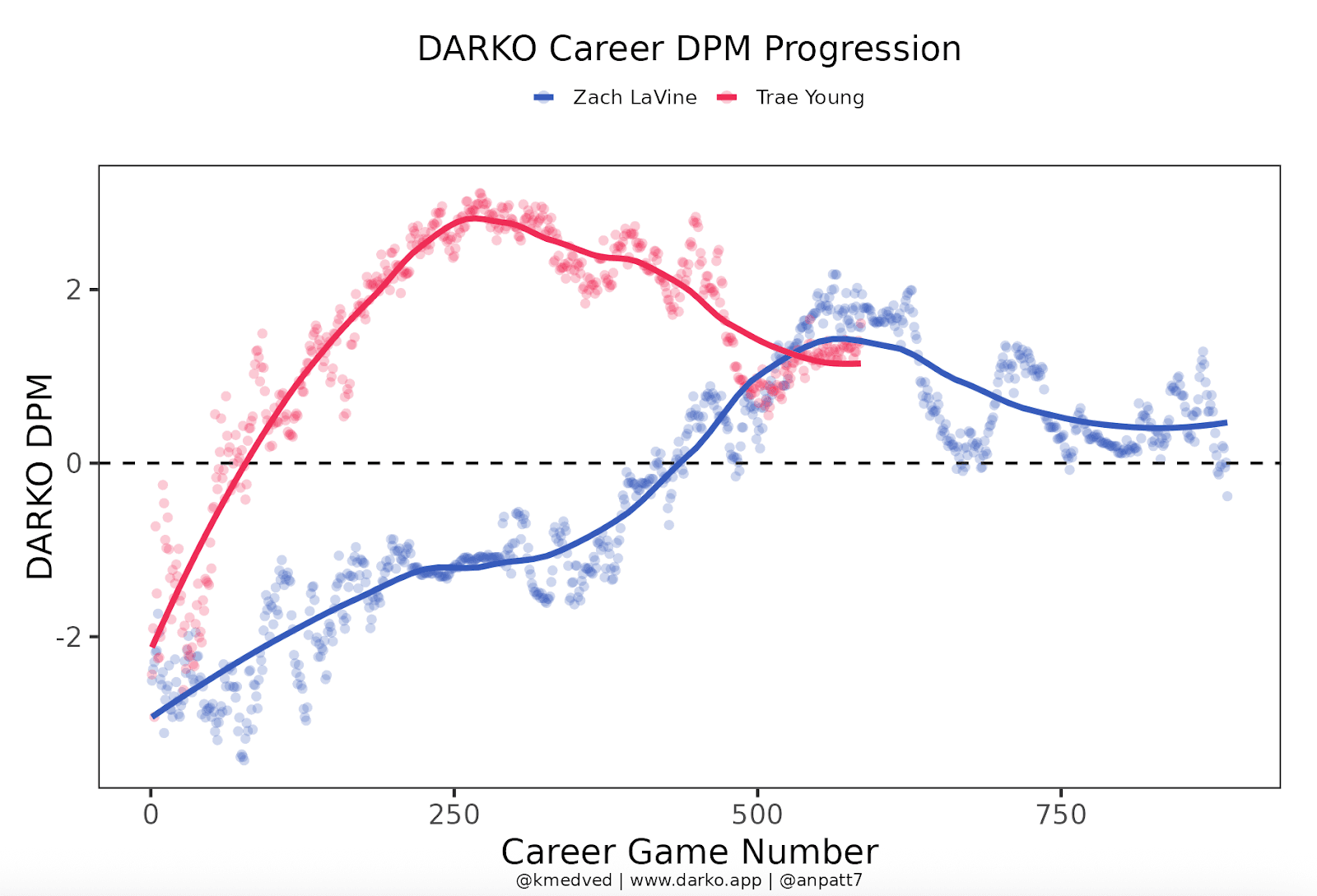

Next year, it could be Trae Young’s and Zach LaVine’s turn to face situationship terms. Both players have All-Star résumés, but it’s unclear how much either star truly affects winning. The curves don’t look great:

Under previous CBAs, extending players like Young and LaVine was a no-brainer, but those days are gone. According to Sam Amick of The Athletic, LaVine is eligible for an extension this offseason, but the Sacramento Kings prefer to pay “a younger player who can be a long-term part of their picture.” The dude is 30.

Young’s next contract is one of the most interesting data points for understanding how NBA teams are operating under the new CBA. He’s still only 26. He’s a four-time All-Star who has already led his team to the conference finals. But his extension window has been open since July, and the silence in Atlanta suggests the team is not exactly eager to give him the bag. The Hawks’ roster also includes ascendant talent like Jalen Johnson, Zaccharie Risacher, Dyson Daniels, and Onyeka Okongwu, and the reality is the team can’t afford to keep everyone home if they give Young a max deal; in a league where depth is king, that spells trouble for Young’s camp. The best teams now jam up their cap sheet with efficiently paid superstars and a slew of complementary depth—overpaying anyone, especially high-end talent, makes building a deep roster impossible.

Simply put, the second apron has re-formed the NBA economy, and these changes are having major impacts on many of the league’s biggest stars. “Free agency is dead,” one executive told me, and when stars like Young and LaVine hit the market, that means they are being greeted by fewer suitors and shorter-term offers. The definition of a max player is now more strict. The dramatic buyouts of Lillard and Beal are precedents—stunning proof that at least two teams would rather light money on fire than be locked into bad numbers for years to come.

In the end, that’s what makes this new CBA era so strange: The NBA is still a star-driven league, but more teams seem to be looking for a good time and not a long time. Situationships aren’t built to last—but they’re still better than a bad marriage.