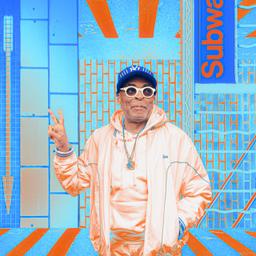

Awards certainly don’t make an actor, but they can make an actor emotional—especially when they come as a surprise. In May, Denzel Washington was awarded an honorary (and unexpected) Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, the event’s highest honor, commemorating his four decades of achievement. Following an introduction by festival director Thierry Frémaux, frequent collaborator Spike Lee presented the award to Washington, who couldn’t mask his emotions. “It’s a great opportunity to collaborate with my brother once again, brother from another mother, and to be here once again in Cannes,” he said of Lee. “We’re a very privileged group in this room that we get to make movies and wear tuxedos and nice clothes and dress up and get paid for it as well. We’re just blessed beyond measure. I’m blessed beyond measure.”

Washington is generally thought of as ultra-composed, smooth, and capable of handling any situation. (Think of how he helped calm Will Smith following the slap heard ’round the world.) It’s the foundation for the whole Denzel aura, which goes hand in hand with his work. But for anyone who needed a reminder of how passionate he is about his craft, there it was.

Washington was in Cannes to promote Highest 2 Lowest, his latest film with Lee. Now in theaters before heading to Apple TV+ on September 5, Highest 2 Lowest reinterprets Akira Kurosawa’s 1963 film High and Low by replacing post–World War II Yokohama with modern-day New York City. In place of the shoe magnate played by Toshiro Mifune is David King, a music mogul at a particularly dire crossroads, portrayed by Washington. Weary with the industry’s rat race after years of success, King attempts a risky gambit: repurchasing a majority stake in his label, Stackin’ Hits Records, to prevent a buyout by a rival. To finance the arrangement, King prepares to put up the bulk of his personal wealth and assets. His plan hits a snag: On the day of the deal, a kidnapper demands a ransom that would consume the necessary funds in exchange for the safe return of his son. To make matters more complicated, the kidnapper mistakenly captures the son of Paul Christopher, King’s friend and body man, played by Jeffrey Wright. Cue an acceleration of King’s crisis of conscience, which propels the film.

Highest 2 Lowest marks Washington and Lee’s fifth film together, beginning with 1990’s Mo’ Better Blues. Their collaboration on these projects is noteworthy not just because the two men are industry titans, but also because they have both benefited from the union. Washington, fresh off a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his work in 1989’s Glory, lent Lee a degree of gravity in the wake of Do the Right Thing, which laid the groundwork for the director’s reputation as a firebrand during a racially polarized time in New York City. Conversely, Lee recognized something in Washington that he believed other directors hadn’t accessed yet. By that point in Washington’s career, he was largely seen through the lens of historical figures like anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko, whom he portrayed in 1987’s Cry Freedom, and Private Silas Trip, the fictional Union soldier he played in Glory. The audacity of Lee’s artistic voice and style humanized Washington, which gave him the space to play messy characters at the dawn of an important but ultimately fleeting moment for Black cinema.

“It gave Denzel the freedom to play roles that had warts,” says Mark Anthony Neal, chair of the Department of African and African American Studies at Duke University. “It allowed him to move away, because part of the dynamic with Denzel is: How does he get out of the shadow of Sidney [Poitier]? It wasn’t just a question of chops, but what Sidney’s performances meant in terms of a certain version of respectability that Black folks were seeking.”

Those Washington roles include characters like Bleek Gilliam in Mo’ Better Blues, the namesake of 1992’s Malcolm X, Jake Shuttlesworth in 1998’s He Got Game, and now King in Highest 2 Lowest. Though this latest movie is a bold and enjoyable ride through the city Lee has the utmost adoration for (from King’s eight-figure Brooklyn penthouse overlooking the East River to the Puerto Rican Day Parade to a studio in the Bronx for a crucial face-off), it’s far from the best of his films. As expected, however, the highlights involve Washington, who, at 70, hasn’t lost a step. He’d already proved that he was one of the best in the business pre-Y2K. And in the 21st century, Washington has flexed even more muscles as an actor and remained at the top of his profession by refusing to rest on his laurels. He is arguably the best actor of his generation. (The New York Times certainly thinks so.) Sometimes, the very best can get even better with time.

Highest 2 Lowest is in conversation with Mo’ Better Blues due to how their protagonists are written and the details of Washington’s performances. He captures the nuances of Gilliam, a brilliant jazz trumpeter and relentless womanizer who is preoccupied with the purity of his art and unconcerned with satisfying audiences at the club where his band plays. Washington does the same with King, whose ear helped him ascend to his lofty place in the entertainment industry but who also wouldn’t be there if he weren’t a ruthless operator on some level. The particular inspiration for the character—be it Berry Gordy or someone else—is unimportant. He’s the quintessential music executive: doing for others, as he’ll surely tell you, but always motivated by self-interest. It’s fitting that Lee’s maximalist tendencies and lack of restraint give Washington carte blanche to let King’s good, bad, and ugly breathe. It’s part of the latitude that working with Lee granted Washington, especially beyond the 2000s.

The 1990s are regarded as a period of abundance for Black film, but that didn’t really sustain. More Black films were made after the 2000s, but if anything, actors like Washington started to become universal stars, which allowed for new and exciting opportunities in some cases. “If you look at Denzel, for instance, what you started to see happen was Black actors who became stars and where Hollywood began to cast outside of race,” Carl Franklin, who directed Washington in 1995’s Devil in a Blue Dress and 2003’s Out of Time, told me in 2021. “A lot of the movies Denzel did that were outside of the ones he did with Spike were not even characters written for Black people. Even Training Day wasn’t, originally.”

Other actors could’ve pulled off the lead in 2001’s Training Day, but only Washington could’ve made Detective Alonzo Harris what he ultimately became. As Harris, Washington is a distinct evil: a dirty cop who relishes abusing his authority. You know what’s scarier than someone with a gun? Someone with a gun, a badge, and no morals. Whenever necessary, Washington creates fear physically. Just as he can be reassuring in other roles, he slides between charismatic and flat-out menacing as Harris. It’s in the way he moves, how he talks, and that Mephistophelian grin he constantly flashes at Ethan Hawke’s earnest officer, Jake Hoyt, like a service weapon. There’s an arrogance exhibited when someone feels they’re above the law they’ve sworn to uphold: They have the power to destroy neighborhoods; we just live there. It’s what makes Harris’s demise, after all his bellowing and threats, so rewarding.

The performance earned Washington the Oscar for Best Actor, which, in tandem with Halle Berry’s historic Oscar win for Best Actress the same year, ignited discussions about representation and the types of roles for which Black actors are awarded. But the Academy was never the one to really validate Washington: The range and consistent strength of his performances did. Even if a film isn’t great, you know what to expect from him in terms of quality.

From that point forward, Washington explored more variety. The version of John Creasy he played in 2004’s Man on Fire was a precursor to Robert McCall of the Equalizer films, which reaffirmed that Liam Neeson isn’t the only lethal boomer worthy of a revenge-fueled action series. Washington captured all of the fictitious Roman J. Israel’s eccentricities in 2017’s Roman J. Israel, Esq. and returned to his Shakespearean roots in 2021, playing the lead in Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth nearly two decades after playing Don Pedro in Kenneth Branagh’s Much Ado About Nothing.

It’s not surprising that, like many actors, Washington has delivered more intriguing performances when playing flawed characters. And thankfully, by the late aughts, when audiences had grown accustomed to seeing Washington as less-than-upstanding men, he was free to unleash his full repertoire, no longer bound by the notion of what the roles he chose meant for Black people at large.

Between performances as compromised small-town police chief Matt Lee Whitlock in 2003’s Out of Time and pilot struggling with alcoholism Whip Whitaker in 2012’s Flight, he played another real-life figure: crime lord Frank Lucas in Ridley Scott’s 2007 biopic, American Gangster. Washington portrayed Lucas as someone with his own set of principles and a propensity for sudden violence. Washington’s Lucas was brazen enough to shoot someone indebted to him on a crowded street—in broad daylight, in the head—to emphasize that disrespect won’t be tolerated, and he slammed a piano lid on his own cousin’s head for his poor impulse control. Washington made Lucas’s hair-trigger temperament feel visceral because of the conviction in his words and actions. If you’ve seen American Gangster enough times, there’s no way you forget that you don’t rub with club soda when attempting to clean blood from an alpaca rug. “You blot that shit!”

So far, the greatest gift of Washington’s versatility has been his post–Training Day villainous turns. Lucas did heinous things in pursuit of the American dream, but he’s not even the main antagonist in that story. Macbeth is an infamous villain whom Washington imbued with new life, but there’s immense weight to that role. Recently, Washington appeared to have the time of his life playing Macrinus, the conniving arms broker in Scott’s Gladiator II. It was a joy watching him commandeer scenes despite not being the film’s focal point. Macrinus, who was formerly enslaved, understood the strategic element of politics and displayed a flair for manipulation. He was the jolt of energy that kept everything and everyone off-balance as he executed his scheme to control Rome. Washington’s supporting performance was the film’s high point because he was as sharp as his gray Caesar trim.

Years before Washington dropped 40 off the bench in Gladiator II, Fences brought together so much of what he accomplished this century under one project. He played Troy Maxson, a garbageman who was a villain to members of his own family and a victim of the time in which he lived. Against the backdrop of 1950s Pittsburgh, Washington was stellar as a man with the gall to ask his wife to help him raise the child he fathered outside their marriage and cold enough to prevent his youngest son from chasing his dreams because racism denied him the chance to do the same. Maxson was incapable of showing love in certain ways because he never received it, and Washington harnessed all of his bitterness and emotional limits. Fences was the third of four films Washington has directed and, as the big-screen adaptation of August Wilson’s 1985 play, a return to his theatrical roots.

Washington, who won a Tony for playing Maxson in a 2010 Broadway revival of Fences, began his career in off-Broadway productions. While doing press for a Broadway run of Othello earlier this year, Washington made it clear that he doesn’t see himself as a “Hollywood actor,” nor does he understand what that means. “I’m a stage actor who does film; it’s not the other way around,” he said during an appearance on CBS News Sunday Morning. “I did stage first. I learned how to act on stage, not on film. Movies are a filmmaker’s medium. You shoot it, and then you’re gone and they cut together and add music and do all of that. Theater is an actor’s medium. The curtain goes up, nobody can help you.”

This was a window into how Washington views his craft. His approach, grounded in his stage origins and ongoing appearances, is part of why he’s remained so precise this century. “I think that’s a thread you can follow in his professional acumen and training from doing A Soldier’s Play, and the cohort of actors who he’s doing that with,” says critic Soraya Nadia McDonald of the 1982 Pulitzer Prize–winning play that was adapted into one of Washington’s earliest film roles, A Soldier’s Story. “They’re all kind of keeping each other sharp. David Alan Grier, Samuel L. Jackson, or even Jeffrey Wright, those are still his peers. You can see how that training pays off and the ways it allows him to deepen David King in a way that he might not otherwise be.”

Highest 2 Lowest isn’t the best of Washington’s performances, but it demonstrates everything that has made him one of the finest actors to ever grace the stage and screen. Even as he’s produced several memes over the past decade, his dominant presence in the zeitgeist has little to do with internet culture, or even the energy of the IDGAF septuagenarian he’s revealed himself to be. The space Washington occupies, impressively, is that of someone who’s still at the top of his game.

His frequent collaborator, Lee, has had a career defined by big swings, but the last 25 years have been a mixture of hits and misses. After 2004’s She Hate Me failed, it made sense that Lee turned to Washington for 2006’s Inside Man, a much simpler film that is still Lee’s most financially successful to date. It was also ideal for Washington because, like all of their work together, it allowed him to broaden his scope. “From my viewing of his career and how I think he thinks about his career, I think Denzel always thinks of himself as a race man,” says Neal. “But he’s also looking for opportunities that don’t reinscribe the fact that he’s a race man. So I think Inside Man was kind of appealing to him—it’s an incredible cast, so he gets to work with some giants in their own right.”

Washington is in the latter stages of his career, so it would be wise to appreciate his sustained preeminence even more now. The great thing about Washington is that he’s always made it easy.