Back in January, film critics Manuela Lazic and Adam Nayman began working together on a long list that initially had more than 100 titles on it, in order to sum up something interesting—if not definitive—about the past quarter century of film. Narrowing things down was hard. They spread out their picks as evenly as they could over this 25-year period and also across a variety of styles, and for the rest of 2025, they will be dissecting one movie per month. They’re not writing to convince each other or to have an ongoing Siskel-and-Ebert-style thumb war. Instead, they’re hoping to team up and explore a group of resonant movies. We’re also hoping that you’ll read—and watch—along.

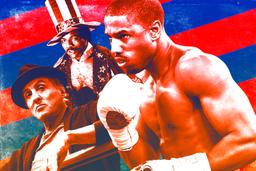

Manuela Lazic: I remember, back in 2015, the clichéd phrase “They don’t make them like that anymore” popped into my mind as I was watching Ryan Coogler’s Creed. Back then, and perhaps even more so today, the film felt like a relic from the past, in a good way. Its narrative and, to an extent, formal classicism were and remain very effective: It’s a Real Movie, like Gladiator or, of course, Rocky. They don’t make them like that anymore, except when they do.

Cynics could say that Creed gains its classical resonance from the fact that it is not only a sequel in the Rocky franchise but also a spiritual remake of the original Rocky Balboa story. Like his new mentor, Rocky (Sylvester Stallone), Adonis Johnson Creed (Michael B. Jordan) dreams of achieving what seems to be impossible and must suffer countless blows to his body and soul before he can find some kind of peace. Stallone’s 1976 masterpiece became a template for gritty sports movies where the fight takes place not only in the ring but also in the mind. Yet Coogler and cowriter Aaron Covington didn’t simply follow this well-established model and let it work its magic; they found a way to raise the stakes so that each expected narrative beat could regain its original power.

Of course, the Rocky Expanded Universe provided some good ingredients for the two screenwriters to work with: Balboa himself, the city of Philadelphia, and, naturally, Apollo Creed’s legacy as both the greatest boxer of his time and a tragic figure. Still, this was well-trodden, even trampled-to-death territory by 2015, and the Rocky sequels had made for diminishing returns. Films arriving later in a franchise often have to come up with new characters or reveal/invent crucial information that had never even been hinted at in previous installments in order to justify their existence; the results can be clumsy and frustrating. Coogler and Covington did just that, but they turned one unavoidable limitation of franchise filmmaking into a strength: They accepted that their film would have a specific place in the timeline of the Rocky-Creed story, a story that had been written and could not be changed. (This is not a multiverse; in fact, our real world and that of Rocky seem to merge when Donnie watches as tourists take pictures in front of the Rocky statue.) They took on the challenge of continuing to tell that story many years later and placed the ineluctable passing of time at the heart of their film.

Donnie claims to want to make it as a boxing champion under his own name, yet he turns to Rocky, his dead father’s former adversary and best friend, for help. Rocky himself is hesitant at the idea of getting back into the ring as a trainer but ends up doing so. The beginning of the film feels a little ropey (pun intended) on rewatch, as if these two characters were brought together to simply relive the past, or at least chase after it. I’m not above enjoying a training montage, but I was waiting for the film to hit me in the jugular, which it finally did when both Rocky and Donnie start confronting their harsh, complicated reality instead of punching their way around it. Donnie isn’t his father, but he has his name, and Rocky can’t ask his protégé to keep on fighting no matter what if he himself won’t. Both had been in denial of the past and its weight, whether it meant old resentment toward the father you never knew or being scared of fighting illness when you remember how ugly that can get. Both have to accept that their pasts—and thus all the previous Rocky films—happened and would continue to impact them, yet they have to move forward. The very juxtaposition of their two bodies, each at a different stage of life and health, drives that point home. (And here’s where I drop the Tarkovsky reference about cinema being all about “sculpting in time.” In this case, bodies are the clay.) They have to remember that it’s all about fighting, not winning—which is, of course, the very idea that made Rocky so compelling in the first place.

I find that same principle running through Stallone’s performance: Whatever the circumstances, Sly is always active and present, always doing something. Like a good boxer, he is, at his best, always on and ready to respond to the moment. This translates into a physical and generous kind of performance, outwardly directed and vibrant. One moment in particular comes to mind: After Rocky has angrily told Donnie that they are not family after all, Stallone sits down and mutters to himself, “Why did you say that?” Most actors would have kept that reflection to themselves, afraid of making the character’s inner feelings too obvious and cheesy. But Stallone’s understanding of authenticity is wider than most actors’. In that moment, you see him lift the veil ever so slightly on the process that goes into that sincerity: He is stating to himself what is driving his character in that moment, namely remorse, which seems to help him connect to that feeling. Perhaps Stallone’s work isn’t always the most subtle, but it often has a directness, a simplicity—dare I say a purity?—to it that comes from a clarity of intention.

Adam Nayman: I love that scene: Rocky’s bewilderment at his own impulsive cruelty—the way he just sort of sits with the implication of his words, like a boxer stumbling back into his corner—is devastating. Forget Clubber Lang (or Apollo Creed): The Italian Stallion has always been better at beating himself up than any brand-name heavyweight.

For all the (often justified) mockery of Stallone’s acting over the years, he’s capable of strange and surprising line readings; when Pauline Kael reviewed Rocky, she compared him to Marlon Brando, and she wasn’t wrong. What is the original Rocky, really, but an expansion of Terry Malloy’s monologue in On the Waterfront about the palooka who could have been a contender, except that this time out, he actually makes it happen? Like his former rival and now lifelong pal Arnold Schwarzenegger (whom he currently leads three Academy Award acting nominations to zero) Stallone is a walking punch line, but when he’s able to connect to his own essential sincerity—something that’s tricky when you’re one of the most iconic American movie stars of all time—he’s skillful and disarming. So much of the emotional impact of Creed is bound up in the simple fact of its costar’s septuagenarian presence, but if Stallone didn’t have the acting chops, none of that would matter. The “Why did you say that?” scene is his Oscar clip, for sure, but other bits are just as good, like his slow-dawning realization of Donnie’s identity when the latter walks into Adrian’s (“There is a resemblance,” he deadpans after finally getting within the jab-length distance from which he often observed Apollo). He also makes a meal of every single one-liner during the training montages (his complaint that “chickens are getting slower” is a dig worthy of Burgess Meredith). Most importantly, Stallone sells the one-two combination of guilt and fear that temporarily strands a historically courageous champion on the far side of his own fighting spirit. “My wife tried that,” Rocky tells the doctor who advises him to begin a course of chemotherapy. “I don’t think I want to do that. It didn’t turn out so good.” Rocky already spends most of his free time in the graveyard with Adrian and Paulie, keeping them abreast of the news of the world; he figures at this point, he’s ready to join them.

Such melancholy is endemic to legacy sequels, but happily, the movie doesn’t succumb to sentiment. Instead, it integrates it into the sort of solid, muscular, sports-movie storytelling that must actually be pretty hard to do because so few people do it well. Coogler’s rhythmic cuts between Donnie’s training and Rocky’s cancer treatment are pure joy—a distillation of the two-fisted relationship between specificity and formula that made the first Rocky great and got stripped away as the sequels systematically exploited all that hard-earned goodwill in the name of grandstanding. I like the Rocky sequels fine, but they’re guilty pleasures; when I reviewed Creed back in 2015 for Reverse Shot, I wrote that its great achievement was how it gave the audience exactly what they wanted while making it feel like a gift rather than a bribe. That’s an important distinction—one that takes cynicism out of the equation. When Bill Conti’s fanfare finally kicks in during the home stretch, it’s not obligatory—it’s electrifying.

Your point about Coogler having to turn a potential limitation into a strength is exactly right. It took a certain amount of guts for him to try to tell Donnie’s backstory straight, considering that the tragic death that left him fatherless as a child exists, canonically, right alongside Dolph Lundgren grunting “I vill break him” in a Russian accent. Rocky IV is one of the tackiest American movies of the 1980s, a veritable hymn to jingoism that finds Stallone proposing glasnost to a crowd of cheering Muscovites before wrapping himself in the star-spangled banner. How do you get from there—from Brigitte Nielsen lurching around in sunglasses, from Stallone trudging through the snow to “No Easy Way Out,” from Paulie’s pet robot—to the moment in the first scene of Creed where the young Donnie is confronted in lockup by Phylicia Rashad’s Mary Anne and, sensing a sympathetic presence, slowly, demonstratively unclenches his fist, a gesture so telling it doesn’t feel written, just performed.

It’s interesting, of course, to look back at Creed in the context of the hugely scaled movies that Coogler made afterward. The film’s success got him scouted by Marvel, and I still admire many aspects of the first Black Panther, including and especially Jordan’s villainous performance, which is so charismatic and compelling that it almost throws that movie off its axis. At the risk of reigniting the “Killmonger was right” discourse, the second Black Panther film suffers from Jordan’s absence just as acutely as it does from Chadwick Boseman’s, although considering the various factors stacked up against its production, the fact that Wakanda Forever even got made (and ended up being halfway watchable) is sort of remarkable. Jordan’s return (times two) in Sinners served as a reminder that he and Coogler are best as a package deal, and I don’t want to give him short shrift in Creed as Donnie—there’s a generosity in the way he cedes certain scenes to Stallone that feels like an extension of Coogler’s own humility in the face of his assignment. He operates the machinery dutifully. But, like Donnie, he also seizes the opportunity afforded by the franchise branding—i.e., by the Creed name, which turns out to be the real title at stake in the movie’s plot—to level up and show off. The boxing scenes are spectacular, especially the single-take throwdown with Leo “The Lion” Sporino, although my favorite bit of fight choreography is when Donnie shadowboxes against a video projection of his father, aligning his movements with those of Stallone in repurposed footage from Rocky II—an ingenious summary of everything the movie is trying to do, as well as of larger themes of generational conflict and longing that mark the film as a vital Obama-era artifact.

The common denominator between Creed and Sinners is a fascination with cultural birthright and inheritance—and the deals with the (literal and figurative) devils facing talented Black athletes and artists trying their best to simultaneously uphold and reinvent certain legacies. The racial politics of the first Rocky were always audacious—an Italian American underdog being instrumentalized as a proverbial tomato can by a savvy Black entrepreneur trying to rile up white grievance—and Creed complicates things interestingly by making Donnie’s opponent an Englishman, played by the mixed-race Tony Bellew. When Creed III came out, I wrote a bit about how the Rocky movies have only ever really been as good as their bad guys. Manuela, where do you stand on “Pretty” Ricky Conlan?

Lazic: I always enjoy the video game–like, “choose your fighter” aspect of sports movies, where a new villain arrives with a special set of skills to challenge our hero—and Coogler leans into that with freeze-frames and on-screen text listing the achievements of each athlete. He presents Conlan and his Scouse accent as exotic but also lifts the veil on the fighter’s economic conditions, walking the line of the original Rocky between entertainment and social realism. But Creed goes beyond nostalgia in that respect too, placing boxing in its current time by showing how the press and social media play an ever-growing role in the economics of the sport itself. Perhaps I’m naive, but I get the sense from Conlan and Co. that, to an extent, fighters today are less protective of their dignity and more willing to do dirty tricks (at least in front of the press) if it means getting more attention. I also think the accent is inherently funny; don’t @ me.

I completely agree with you on Coogler’s interest in cultural legacies, and I wouldn’t be surprised if Sinners made the list of the most significant films of this century one day. Both of these movies explore the emotional quagmire that comes with inheriting a history that is at once full of beauty and pride and marked by cruelty and suffering. It’s interesting to compare the endings of Creed and Sinners, too, for what they say about the ways to carry such a complicated memory. Donnie finds hope and purpose in community and love, and Stack, having been turned into a vampire, gets to live in a sort of forever alternate reality where he can be with the love of his life (a white-passing woman whose love he couldn’t accept during his natural life) and (with any luck) never get killed. This jump into fantasy allows Coogler to push his exploration even further, not to offer a solution but rather to expose how heavy the burden of racism and persecution is.

Mortality is a big part of both Creed and Sinners. Boxing can kill you, and, as Rocky more directly experiences, so can time itself; meanwhile, Stack and his twin, Smoke, as well as their cousin Sammie, are offered immortality as a way to finally detach from their painful histories, an attractive proposition that would nevertheless come with another kind of isolation and suffering. As you said, when Rocky at first refuses to fight his cancer, it is as though he’d rather join Adrian than carry on living with the pain of her absence, as though he could at last let go of his past. But he changes his mind, just as Donnie and Sammie refuse to leave their legacies behind, however traumatic they may be. Instead, they honor them through their art. Sinners moved me immensely for its sincerity and belief not in a perfect exit but in some comfort being attainable: There is no easy way to live with oppression and suffering, yet one can turn to community and art to lift that burden. The film’s boldest sequence travels through time to pay tribute to how music has soothed oppressed people since the beginning of time, an idea Coogler first planted in Creed, with Bianca’s (Tessa Thompson) determination to make the most of her musical talent before she completely loses her hearing. Coogler doesn’t offer hope: Bianca won’t regain her hearing, and Donnie doesn’t win his last fight. Instead, he wants to guide his audience toward relief and joy.

Nayman: That’s a great read on the role of music in Creed. It’s a measure of Coogler’s skills as a dramatist—and his affectionate but thoughtful regard for Rocky—that Bianca is both an analogue of Talia Shire’s Adrian and a very differently developed sort of character: not a lonely heart brought out of her shell by the courtship of a big, lovable lug but a capable and ambitious artist who’s on firmer ground with her practice than Donnie is with his. Crucially, Bianca is also a Philadelphian who can give her new boyfriend, and the audience, the same kind of guided civic tour that John G. Avildsen orchestrated in the original film—local color being a kind of secret weapon in the Rocky series, which has always made the most of having the Italian Stallion ply his trade adjacent to the corridors of American political power and in the shadow of monuments dedicated to the Founding Fathers.

You mentioned the Rocky statue earlier on, and Creed doesn’t do as much with its iconography as you might expect—those tourists snapping photos are glimpsed so quickly that it’s barely a scene, more of an annotated transitional bit en route to the genuine article. It’s interesting to note that the statue was actually commissioned for the filming of Rocky III—an example of life not only imitating art but bending to its whims, depending, I guess, on whether you consider Rocky III art (I do). And, actually, the definition of art is central to the legacy of the Rocky statue; city officials argued that the piece was really just a glorified movie prop and had it moved to the front of the Philadelphia Spectrum. This strange turf war continued for the better part of 20 years, with the bronze Rocky being carted back and forth between locations depending on the needs of the sequels until 2006, when it resumed its rightful place at the bottom of the museum steps in perpetuity. Is it funny that it took the promotional launch of Rocky Balboa for the piece to be made permanent? Sure. Is it moving that, at the ceremony, the mayor of Philadelphia called Stallone—who was born in New York and lived there until he was 15—Philadelphia’s “favorite adopted son”? Sorry, just a second—I have something in my eye.

As we were writing this essay on Creed, it was announced that Sylvester Stallone will be one of the recipients of a Kennedy Center Honor in December—the first one supervised (and, apparently, hosted) by Donald Trump after he cleaned house earlier this year. This is not surprising: Stallone was already deputized as one of Trump’s Hollywood ambassadors and already compared the 45th and 47th president to both Rocky Balboa and George Washington. But the tension between Stallone’s politics and the direction of the Rocky series is fascinating. After cowriting Creed II—directed not by Coogler but by Steven Caple Jr.—Stallone begged off part three, citing a difference of opinion with both producer Irwin Winkler (a longtime industry sparring partner) and Jordan, who was moving into the director’s chair. “That’s a regretful situation because I know what it could have been,” Stallone said in an interview with The Hollywood Reporter. “I wish them well, but I’m much more of a sentimentalist. I like my heroes getting beat up, but I just don’t want them going into that dark space. I just feel people have enough darkness.”

He’s right about one thing: People have plenty of darkness right now. I wouldn’t exactly say that the movie Stallone did help to make this year—that’d be A Working Man, in which Jason Statham lays violent waste to a child-trafficking ring—is light, but it is unambiguous about its hero. Statham gets beaten up, gets off the canvas, and storms an Epstein-style bacchanal, leaving no survivors. The movie opened two weeks before Sinners and actually did pretty well, grossing nearly $100 million on a $40 million budget; I doubt it’ll be an Oscar contender (or one of the most significant films of the century), but I enjoyed it and its evocation of Stallone’s hilariously reactionary worldview well enough. He’s a sentimentalist all right: At one point, the characters played by Statham and David Harbour get misty talking about the latter’s gun collection.

I’m wondering what Stallone’s Kennedy Center clip reel will look like: Rocky will be on it, of course, and hopefully so will Creed (I still think he deserved that Oscar over Mark Rylance). Overall, Stallone deserves the plaudits, even if the context gives one pause. To return to the way you started this dispatch, it’s easy and cliché to look at him and see a relic: a battered culture warrior who doesn’t know when to stay down. Ryan Coogler, meanwhile, is very much a director of the moment, partly because he has an eye to the future—he negotiated the rights to Sinners, which means he’ll control the film totally in 25 years and he can keep his studio from pumping out sequels. “I wanted it to be a holistic and finished thing,” Coogler told Variety about Sinners, and considering his ordeal on Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, that’s fair enough. The great paradox of Creed is that it’s a sequel that’s also a holistic and finished thing—impossible to separate from its franchise yet solid enough to stand tall on its own two feet. Like the Rocky statue, it’s a work of popular art, and it’s not budging anytime soon.