“Criticism,” wrote Roger Ebert in 1988, “quails in the face of The Naked Gun.”

This was not a complaint; Ebert adored The Naked Gun, which he considered an absurdist triumph. His point was that David Zucker’s surprise blockbuster—adapted with his brother Jerry and their ZAZ collaborator Jim Abrahams, from their own short-lived and much-loved ABC procedural spoof, Police Squad!, starring Leslie Nielsen as the clueless LAPD investigator Frank Drebin—was a work of such shrewd and lucid stupidity that it was pointless to try to deconstruct it.

Or to recap it: Inventorying the original’s greatest verbal and visual gags—a chalk outline floating on the surface of the harbor; the anti-graffiti wall that spray-paints punk kids; the most iconic stuffed beaver in movie history—would take a long time. It would also take away the element of surprise, one of its makers’ greatest weapons. Beginning with their cheerfully subversive spoof anthology The Kentucky Fried Movie—which features a mock PSA so good it was basically cannibalized whole by The Simpsons—the ZAZ mandate was basically to produce three-dimensional issues of Mad magazine; their favored tactic was the sort of nuclear-grade non sequitur that seemed to explode out of nowhere even while the punch line was hiding in plain sight. The Naked Gun represented the apotheosis of this approach: Handed a fancy cigar by a suave villain, Nielsen’s Frank responds to the offer—“Cuban?”—by politely replying, “No, Dutch Irish … my father was from Wales.” Later, when confronted by a pair of partygoers who are surprised to see him, he parries their startled exclamations—“Drebin!” “Frank!”—with a curt “You’re both right.” I could go on, but I won’t; there are too many. “Don’t let anybody tell you all the jokes before you go,” Ebert added at the end of his own review, which, to its credit, did no such thing.

There is slightly more to analyze in Akiva Schaffer’s surprisingly tight, spiritually pure update of The Naked Gun, which is technically the fourth film in the franchise but carries itself with the confidence of a successful revamp (the lack of a silly subtitle, à la The Smell of Fear or The Final Insult, is itself an act of heroic restraint). The film has plenty of jokes that are too good to spoil and also some bad ones that are even better; to paraphrase another ’80s classic getting a legacy sequel this fall, it’s a fine line between stupid and clever, and Schaffer—who between this and Hot Rod and the terrific Pop Star: Never Stop Never Stopping is arguably the most consistent big-studio comedy director of the 21st century—obliterates that boundary with aplomb. Brevity is the soul of wit, but there’s also something to be said for turbocharged idiocy. At 85 minutes, The Naked Gun’s inverse ratio of running time to gag density recalls David Wain’s 2014 classic, They Came Together, which ingeniously split the difference between reverence and contempt for its chosen subgenre of early ’90s romantic comedies.

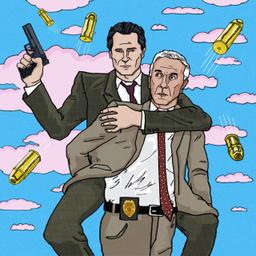

Wain was working with the freedom to take cheap shots at the objects of his satirical affection, but The Naked Gun is, on some level, honor bound to its predecessors as a piece of brand extension. This relationship could be a cue for compromise, but Schaffer uses it instead to clarify his inventions for this particular piece of intellectual property: He’s a caretaker rather than a gentrifier, and he knows his way around the neighborhood. Kneeling humbly before a portrait of his dearly departed dad, Liam Neeson’s Frank Drebin Jr. expresses a desire to make his old man proud while also carving out his own style. It’s an earnest, paradoxical sentiment that the actor plays straight, demonstrating the samurai-like discipline endemic to the material; the only way to play this role is to go all in with a poker face, and then never fold.

In a modest but real way, Frank Drebin is a hall of fame movie cop—a figure on the level of Frank Bullitt, “Dirty” Harry Callahan, and “Popeye” Doyle, whose two-fisted legacies are subsumed into Drebin’s own mutant DNA. With his square jaw, deep voice, and premature shank of silver hair, Nielsen—a refugee from several decades’ worth of redolently cheesy disaster movies and prime-time serials—was a perfectly fatuous and fallible mock avatar for Reagan-era authority figures. This link was first forged in Airplane! when the actor recited Ronnie’s inspirational “Gipper” monologue from Knute Rockne All American and then made explicit in The Naked Gun’s hilarious opening prologue, where Frank infiltrates and decimates a meeting of foreign bogeymen (“I have the Americans believing I am nice guy”). Later, back on home turf in Los Angeles, he ends up embarrassing the queen of England, straddling Her Majesty in a tasteless tableau that doubled as a summary of the USA’s postcolonial Oedipus complex. The key to Nielsen’s performance was his utter guilelessness; by measures hapless and intrepid, he turned himself into a vacant, hallowed icon.

While obviously a bigger star than Nielsen (and a more capable actor), Neeson is also a walking form of shorthand; he sweats credibility and embodies the conventions and clichés of 21st-century action cinema more than any other working actor. More importantly, at 73, he’s old enough to serve as a living link to the analog era when ZAZ consolidated their influence in the first place. His wizened old-pro presence helps sell the idea that Frank Jr. is a man out of time, a faux-reactionary conceit that dovetails with the film’s throwback approach. Rather than trying to find a way to bring The Naked Gun into 2025, the film turns millennial culture and references into a series of obstacles for Neeson to steamroll—not in defiance of political correctness but out of respect for the idea of movie comedy as a stand-alone genre (as opposed to epic-bacon seasoning for superhero sequels). The film’s script offers a deceptively scattershot barrage that manages to wing a few expressly contemporary targets (Elon Musk, Tesla) while still appealing to Schaffer and executive producer Seth MacFarlane’s cohort of once impressionable, now aging Gen Xers—a collective sense of humor that was forged by rewinding their VHS cassettes to watch Nielsen and Priscilla Presley roll around in full-body condoms.

Presley appears in the new Naked Gun just long enough to contribute a pretty good shocked reaction shot. The other original cast members (including O.J. Simpson) are duly memorialized by posthumous photographs, but there’s very little of the nostalgic melancholy that recently suffused Happy Gilmore 2 (a much weirder movie, but with its own integrity). Nielsen’s chemistry with Presley was the stuff of legend, and Pamela Anderson fills the latter’s stilettos with similar agility. Her character, Beth Davenport, is a true-crime novelist with shades of Sharon Stone in Basic Instinct, making her a potential suspect in the supposedly-but-clearly-not-accidental death of her big-tech-employee brother. To the extent that the movie has a story line, it involves Frank’s pursuit of the real killer, who orchestrated Beth’s brother’s crash to get his hands on an object we see labeled, in close-up, as “P.L.O.T. Device.” There’s a palpable delight in seeing Anderson—always an underrated comedian—chopping it up with her costars; with apologies to her perfectly serviceable performance as a fading dancer in The Last Showgirl, this is her career-best role, shaming several decades’ worth of casting directors who failed to hook her up with elite goofballs capable of maximizing her talents. If there were any justice in the awards-voting process—which there isn’t, of course—she’d be part of the conversation, as would Danny Huston, who imbues his Silicon Valley villain with an unctuousness at least within spitting distance of Ricardo Montalban (minus the rich Corinthian cadences).

In truth, both Anderson and Huston could have been in The Naked Gun a little bit more; ditto Paul Walter Hauser as Frank’s sidekick Ed and C.C.H. Pounder as his boss (a piece of casting that seems to have emanated from a throwaway bit on It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia). Given the movie’s slightly dodgy pacing (the best stuff is front-loaded), it’s a good bet that these actors—and other fleetingly glimpsed cast members, like Moses Jones as Nordberg Jr.—actually shot plenty of additional material and that Schaffer endeavored to be as ruthless as possible in the editing room. The result is lean and, if not mean, then admirably aggressive and single-minded. There’s something refreshing—and invigorating—about a comedy that just keeps throwing punches, and if, in the end, The Naked Gun lands more jabs than haymakers, the points add up.

I said at the beginning of this review that I would try to avoid spoiling jokes, but I have to mention one. Early in the film, while walking through the police station with Ed in tow, Frank passes an office labeled “Cold Cases” that resembles a walk-in freezer. The sign is on-screen for maybe five seconds; it’s a good bet that many viewers won’t catch it, and that a bunch of the ones who do will barely crack a smile. For some of us, though, this blink-or-miss-it piece of art direction justifies the entire enterprise. Not only does criticism quail in the face of The Naked Gun, it throws its hands up in grateful surrender. No notes, guys.