Back in 2010, James Gunn made his sophomore feature film, Super, a cheap, surprisingly nasty little movie about a socially inept short-order cook who cosplays as a violent masked vigilante. Released in the wake of The Dark Knight and with Iron Man ascendant, Gunn’s film riffed on nascent superhero mania by mapping the fine line between genuine righteousness and ambient, all-American rage. “You don’t butt in line!” stammers the shabbily attired Crimson Bolt (Rainn Wilson) as he stares down the petty criminal who he imagines to be his arch enemy. “You don’t sell drugs! You don’t molest little children! You don’t profit off the misery of others! The rules were set a long time ago! They don’t change.”

Fifteen years later, Gunn is no longer in the indie-movie trenches. Instead, he parlayed his post-Tarantino instinct for recycled pop standards—exemplified by the oh-so-’70s needle drops in Guardians of the Galaxy—into an exalted status as a comic-book-movie specialist. No less than his fellow DC-Marvel switch-hitter Joss Whedon, Gunn’s work exemplifies a cultural trajectory defined by the revenge of the nerds, but he’s more apt to cultivate ugliness. Hence the paradox of his new “soft” reboot of Superman, which finds a filmmaker defined, at his best and worst, by glibness dealing with a character whose legacy is sincerity itself.

In interviews, Gunn has done his best to show he isn’t losing his edge, but his anti-establishment swagger is hard to square with a $225 million budget and a mandate—from noted cinephile David Zaslav—to give DC Studios’ flagship property “a coherent and creative brand strategy.” Gunn wants to have his franchise and subvert it, too. “I don’t need to see Baby Kal coming from Krypton in a little baby rocket,” he snarled in an interview with The New York Times. “We have watched a million movies with characters who don’t have their upbringing explained … who cares?”

So what do we need to see in a Superman movie in 2025? Gunn’s answers include, but are not limited to: Lois Lane uploading a story into the Daily Planet’s CMS; Jimmy Olsen cruising through the red-light district in search of a recurring hookup listed in his phone as “Mutant Toes;” a frenetic chase scene through vomit-colored CGI that resembles Mario Kart’s Rainbow Road; Nathan Fillion in an Anton Chigurh haircut; a potentially important supporting character reduced to a drunken sorority girl; and a million monkeys at a million keyboards rage-tweeting about a bizarro version of the Epstein files. These details—and there are a lot of details—are eccentric without being particularly inspired. Gunn’s Superman is an overstuffed buffet composed almost entirely of Epic Bacon. Its tone is anxious, and pent-up: If there’s a character on screen who allegorizes Gunn’s directorial approach, it’s Nicholas Hoult’s Lex Luthor, a manic, increasingly unhinged mogul striding restlessly through his high-tech command center, cashing his own blank checks and trying to find something new and edgy to say about a superhero whose greatest and most enduring virtue is that he’s a benign cipher—an icon as easy to read as an open comic book.

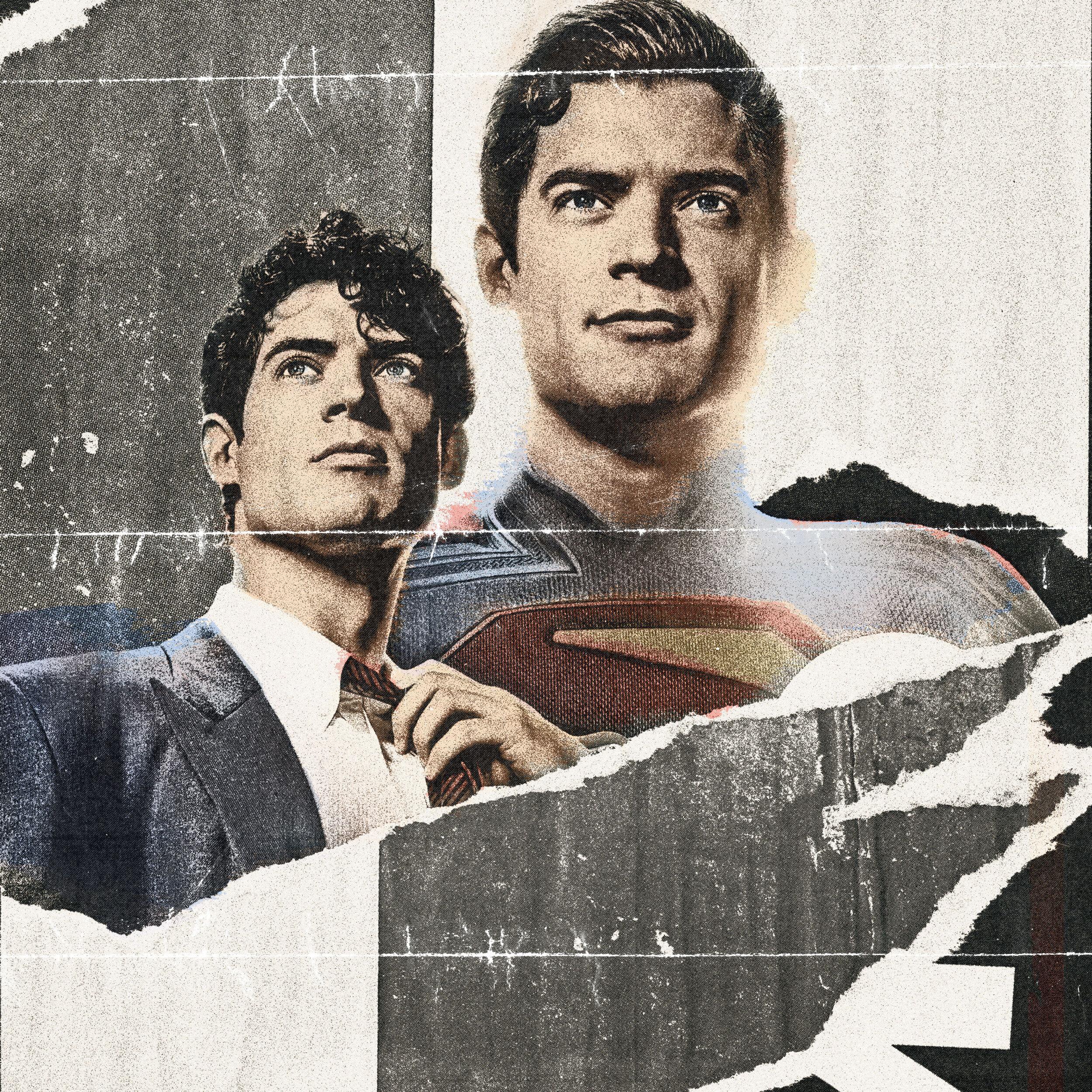

The inherently polarizing posture of Gunn’s cinema has been exacerbated by a fan culture that loves to use filmmakers as proxy combatants, and when it comes to the Superman movies, it is always clobbering time. At the moment, the aggressors are punch-drunk Zack Snyder loyalists, who have supposedly tried to tank Superman’s prospects in advance by posting spoilers and negative reviews and reserving tickets without paying for them. Cult leaders do inspire devotion, but in reality, Gunn and Snyder—who worked together on 2004’s intense and weirdly reactionary revamp of Dawn of the Dead—are on good terms, as evidenced by their recent, kayfabe-breaking dual cameo on Rick and Morty. (“More creatine, please,” says Snyder’s animated stand-in, waiting politely in line at the Warner Bros. commissary. “Your biceps are bigger than my head,” sighs Gunn.) For all the enmity between their respective fan bases—who frankly deserve each other—it’s worth pointing out that Gunn and Snyder’s films share a conceptual pivot point as far as their big blue leading man goes. Namely, the provocative and dramatically fertile idea—only barely developed in Richard Donner’s original 1978 Superman and pushed to the side in its increasingly cheesy sequels—that the erstwhile Clark Kent is not only an alien, but a potential invader whose corn-fed Boy Scout shtick belies some freaky, fundamental difference with humanity itself. Cue David Carradine’s wonderful monologue in Kill Bill: Vol. 2, which implies that the whole Clark persona is a form of trolling—an extraterrestrial Übermensch’s parody of workaday frailty.

For Snyder, a natural-born expressionist who leans into big, building abstractions about honor and masculinity (he’s the greatest living Klingon filmmaker), the Superman myth offered a chance to flex his stylistic muscles and mount bombastic (and occasionally quite beautiful) tableaus. The sequence in Batman v. Superman when Henry Cavill touches down in Mexico during the Day of the Dead has the visual panache of a great graphic novel. Gunn is a less gifted image-maker than Snyder, and, despite his perpetually juvenile sense of humor—which worked better 20 years ago in the low-budget, gross-out B-movie context of Slither than, say, The Suicide Squad—he’s also far more politically correct, framing Superman as an “immigrant” narrative about the importance of kindness.

That Gunn’s comments have inflamed the MAGA crowd is, ostensibly, a point in his favor: Getting two thumbs down from Kellyanne Conway and Jesse Watters on Fox News should be worn as a badge of honor. But incurring the wrath of rabid right-wing ideologues doesn’t mean that the geopolitical angle in Superman is particularly acute on its own terms—or that Gunn has the courage of his convictions. When asked in that same Times interview whether the standoff between the fictional countries of Boravia (a DC comics standby since World War II) and Jarhanpur was referring to any specific real-world conflict—whether Russia-Ukraine or Israel-Hamas—the director demurred, “Oh, I really don’t know.”

Given Gunn’s previous antipathy toward Vladimir Putin, it’s easy enough to see the dilapidated Boravian strongman Vasil Ghurkos (Zlatko Buric) as the dictator’s toothless analog (the less said about the depiction of Jarhanpur as a helpless peasant population holding the fort with pitchforks, the better). As the film opens, Ghurkos is trying to annex his less prosperous neighbor, only for Superman to swoop in like a one-man United Nations. His unsanctioned (but bloodless) intervention is taken by world leaders as a shot across their collective bow, and gives Luthor—played by Hoult with the same gelignite gleam he brought to his domestic terrorist in The Order—the opening he desires to present himself as the great leveller, a concerned citizen with the means to watch the proverbial watchman. His pitch is to use his own private army of Metahumans (including a masked thug with suspiciously Kryptonian powers) to keep Superman in check; his plan also involves deploying bots as a form of digital kryptonite, chipping away at Superman’s reputation one hashtag at a time.

Given Gunn’s own tumultuous history with the social media horde, Superman’s criticism of online mobs and cancel culture feels personal: an efficient device for dragging an old-school character into the present tense. It’s a running joke that Superman resents social media and wants to control his image. When Rachel Brosnahan’s Lois Lane cajoles Supes into an on-the-record exclusive—which is easily done, since in this iteration of the story, she and Clark are lovers who treat his secret identity as a running joke—she touches that nerve, and a few others. And while the great His Girl Friday–style comedy about the Daily Planet remains to be made, Gunn and his actors manage to work up some sexy screwball energy in those scenes dealing with journalistic ethics—a quality that’s been in short supply since the glory days of Christopher Reeve and Margot Kidder, whom David Corenswet and Brosnahan duly evoke without lapsing into imitation.

That’s a high compliment, by the way, and Corenswet—who’s got bigger puppy-dog eyes than Krypto and what Pauline Kael referred to as Reeve’s “pop jawline”—sells the through-the-wringer aspect of Gunn’s screenplay, in which Superman is frequently reduced to a kind of physical and rhetorical punching bag. For instance: An opening title card informs us that, as of “three minutes ago,” our hero has lost his first ever battle, and then, after he’s nursed back to health by his own private pit crew of helper robots, he goes down again.

Making Superman vulnerable isn’t the problem, though—it’s that Gunn doesn’t trust the Man of Steel to be the main event. Predictably, he styles Superman as a structural clone of The Suicide Squad and Guardians of the Galaxy—a sprawling, noisy ensemble piece that tries to elevate a claque of second-tier superheroes to the headliner’s level by association while also kidding their also-ran status. It’s a setup that would probably seem fresher if Thunderbolts* hadn’t done basically the same thing earlier this year, with better characters and jokes. The members of the media-savvy “Super Gang” are all charming enough on their own terms—with Fillion channeling his mock-alpha-dog performances in Super and Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog as the sullen, narcissistic Green Lantern/Guy Gardner—without ever seeming essential. This disconnect could have worked if used satirically, and Gunn does score one genuinely hilarious set piece in this vein, when Guy and the B-team are reduced to a soundless background sight gag while Lois and Clark talk about more important things. Elsewhere, Edi Gathegi’s tech-support virtuoso Mr. Terrific gets his own kick-ass action sequence, shot (natch) in a single, hot-shit long take and scored (natch) by an ironic, contrapuntal music cue. It’s impressive in an airless sort of way, with all the excitement of a contractual obligation; when it’s over, Brosnahan—who doesn’t have nearly enough to do—whispers “Holy shit,” as if cuing us on how to react.

There’s nothing wrong with rib-nudging, of course, and Superman’s desire to give the audience a good time isn’t all bad. Some forms of shorthand are more eloquent than others, of course, and Gunn’s reliance on electrified snatches of John Williams’s vintage theme music feels counterintuitive in ways that cut to the heart of the movie’s flaws. The contrarian impulse that compels Gunn to puff up and scoff “who cares?” when it comes to depicting Superman’s backstory—and also to revise Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s space-Moses origin myth by revealing Jor-El (played in holographic form by an actor not worth spoiling here) sent his son to Earth with less than benevolent intentions—bumps up against the commercialistic desire to not alienate the faithful. Basically, Gunn is trying to tear something down and build it up at the same time, and all of that lavishly subsidized indecision—blandly shot, mechanically paced, and punctuated by the kind of forced comic banter that needs ace deadpan comedians like Bradley Cooper or Dave Bautista to work—becomes hard to take after a while.

It’s telling that the most spectacular imagery in Superman concerns an inter-dimensional rift that threatens to rip the world clean in half. Perched on the edge of the uncanny valley, the best Superman and his new pals can do is try to zip things back up again: superheroism as a return to the status quo. (And, in case anybody’s worried that the stakes are too apocalyptic, Gunn makes sure there are no on-screen casualties.) As for Superman’s big, climactic speech about the failures that make him human, it’s filled with exactly the sort of vapid, hug-it-out clichés that Gunn would have kidded in his salad days, the kind that he still hasn’t quite grown up enough to sell on their own earnest terms.

At one point in Superman, Clark tells a skeptical Lois that he considers himself to be “punk rock.” It’s a laugh line—and a funny idea—but there’s also something cynical about a $225 million movie that keeps insisting that cynicism is the enemy. Is Superman speaking for himself or for a filmmaker whose migration from edgelord to nicecore suggests a kind of lucrative compromise? Is Gunn’s take on Superman radically optimistic or savvily noncommittal? Is it punk rock or an ersatz cover version? Is it deceptively complex or just chaotic and convoluted? Does it follow the rules or break them? Who can say? Or maybe, to Gunn’s point, the better question is: Who cares?