This summer, people can’t stop talking about the story of an idealistic immigrant who opposes an unjust war and wants to help people and, as a result, earns the wrath of a vengeful billionaire and finds himself mired in a right-wing smear campaign. There’s also been a lot of interest in the upcoming Superman film.

James Gunn’s colorful, nostalgic, Silver Age–indebted take on the original superhero is set to serve as a starting point for the rebooted DC Universe. Obviously, the writer and director couldn’t have anticipated just how uncannily close the themes of his film would mirror the cultural response to the insurgent campaign of New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani, who seems to live rent-free in the head of billionaire financier Bill Ackman and whom Fox News now treats as the greatest threat to the republic since Barack Obama. Sometimes, Gunn admits, art imitates life to an uncomfortable level.

“It’s weird. I actually don’t feel good about it, to be honest with you, because the world is closer to the world of the DCU now than when I wrote this movie two and a half years ago,” reflects Gunn. “The only thing that we’re missing is kaijus and giant imps floating above the city.”

Even amid a rather crowded field, Gunn was one of the most high-profile and outspoken Hollywood types to criticize the first Trump administration. MAGA types struck back by resurfacing offensive posts he made during the early days of social media, which led to Disney firing him in 2018; he was eventually rehired following a public outcry and a show of support from the Guardians of the Galaxy cast and several other entertainers.

The world is closer to the world of the DCU now than when I wrote this movie two and a half years ago. The only thing that we’re missing is kaijus and giant imps floating above the city.—James Gunn, on the parallels between 'Superman' and the current political environment

In 2022, he became the co-CEO (alongside producer Peter Safran) of the new DC Studios, which Superman will officially launch, with more DC films, shows, and cartoons to follow, some of which he will personally write. These days, Gunn’s social media presence is much more self-promotional and much less political. “I have found that railing online about stuff is not a great impetus to actually change people’s hearts,” he says. “If I could do anything, it’s open people up a little more.”

It would be reasonable to assume that, given Gunn’s past experiences and new responsibilities, his movies would avoid capital-P Politics. This assumption would prove incorrect. Superman, based on the character created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster in 1938, directly comments on propaganda and media manipulation and features an oligarch stoking fears about an immigrant in an effort to seize power. And if you also wanted to project a critique of billionaires on top of it, it wouldn’t exactly be a reach. Gunn didn’t plan to critique our modern dystopia, he insists, but you can’t control the world your film is released into.

“I’m telling a story that is authentic to who I am and how I look at the world. This movie felt good from the beginning because it is about a person who is good and who’s struggling with the way he looks at himself,” he says. “And he’s not perfect. But he’s kind and old-fashioned. In a way, Superman, he’s the biggest rebel there is because of that. Especially in today’s world. You can say that’s political, but it’s also just the way I look at life.”

A film featuring a dog with superpowers (the delightful Krypto); the jerky Green Lantern, a.k.a. Guy Gardner (the also delightful Nathan Fillion); and the above-mentioned kaiju can’t be called grounded, per se. But like the best genre storytellers, Gunn knows how to use fantastical, larger-than-life elements as a way to reflect on, amplify, and ultimately comment on recognizable human emotions and behaviors. After all, this is the man who, in the first Guardians of the Galaxy, made the world fall in love with a talking, gun-toting raccoon and then broke our collective heart by killing off the tree man Groot.

“It’s not the idea that ‘What if Superman were real and in our world?’ that we’ve seen before,” says Fillion, who voiced the Hal Jordan version of Green Lantern in several animated DC films. “His entry point was, ‘What if the real world was the comic book world? And we lived in that world?’ And I found that to be very new and very exciting.”

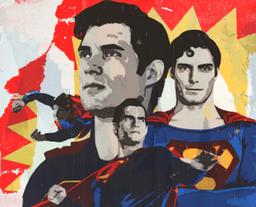

The new Superman strongly embraces the character’s comic book roots (Grant Morrison’s All-Star Superman is an avowed influence), offering up wild, pulpy ideas; world-shaking battles; and a bold, vibrant color scheme. It’s easily the best cinematic take on the character since 1980’s Superman II. But even with all the comic-y elements, Gunn never loses sight of the two central relationships of the film—the one between Superman (David Corenswet) and his nemesis, Lex Luthor (Nicholas Hoult), and the one between Clark Kent and Lois Lane (Rachel Brosnahan)—and it’s this human touch that helps the movie soar where previous attempts at bringing the character to life failed to lift off.

To fine-tune the dynamic with Luthor, Gunn and Hoult (who plays sneering little bitches with an aplomb that no actor of his generation can match) zeroed in on the tech oligarch’s resentment of Superman, who at the outset of the film has been active for three years. “[Luthor] was the smartest man in the world. And then this guy comes along who’s flying and wearing what he perceives as a clown costume, with dimples and a square jaw and a disarming grin. And you are now all of a sudden a distant second,” Gunn says. “And for a guy who wasn’t really led by altruism but was led by his own need for power and love—I think Lex wants to be loved—he turns that envy, that jealousy, into a spiritual quest to destroy Superman, while rationalizing that he’s basically doing something good for humanity.”

When it comes to Lane, the chemistry and mutual attraction between Clark (Corenswet has the sort of “aw, shucks” Midwestern charm long missing from on-screen portrayals of the character) and Lois (Brosnahan is well-versed in rat-a-tat dialogue from her time in The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel) are tempered by apprehension on Lane’s part and philosophical differences about Superman interfering in geopolitical affairs and other ethical quandaries. (They also have starkly different tastes in music. Turns out Superman is a pop-punk guy, whereas Lane is more of an Against Me! fan.)

“I think she’s unsure whether this is a healthy situation for her. I mean, after all, he does wear a costume and flies around and fights crime and also pretends to be a geek and then pretends to be something else,” Gunn says. “He’s a confusing guy, and she’s so attracted to him. That’s something that we have never really seen on-screen. Right away, they’re making out.”

The film also flips audiences’ expectations by having Lane both help rescue Superman and thwart Luthor’s plans, via the power of investigative journalism. (Spoiler if you thought Superman wouldn’t win in the end.) “I don’t think there’s anything wrong if Lois is ever a damsel in distress. But I did want Lois to be her own person,” Gunn notes. “I do find it important to write full-fledged characters, no matter what their gender is, and allow Lois to be a full person.” Finding the humanity in fictional characters, no matter how fantastical, has always been one of Gunn’s strengths. Watching his films, it’s clear he loves the people and creatures he puts on screens, even the bad guys. But it took a long time for Gunn to let anyone give him the same love he shows to his on-screen creations.

Born in St. Louis, Missouri, Gunn, now 58, was a horror movie fan from a young age who also tried his hand at fronting punk bands and creating political cartoons. He wound up dropping out of film school, and after getting sober at the age of 19, he eventually earned an MFA from Columbia University. He also received (perhaps less prestigious but maybe more utilitarian) tutelage from Lloyd Kaufman, a filmmaker and producer whose Troma Entertainment has given bored teenagers low-budget, gory entertainment for decades and who proved that anyone can make a film if they try hard enough, taste and financial resources be damned. Gunn learned a lot from the experience. His first screenwriting and associate director credit was for Troma’s transgressive 1996 adaptation Tromeo and Juliet; in 2000, he published the novel The Toy Collector, and he hasn’t slowed down since, working on everything from low-budget indies to scripts for studio-friendly reboots.

“I think he was a maniac, but he was the best kind of maniac. You just have to keep going and keep moving. I think that in some ways, James’s superpower is that when he gets an idea, he doesn’t abandon it, he completes it, and then you’re able to move on to the next thing, and you leave a body of work in your wake rather than a bunch of unfinished projects,” says his brother Sean, who appeared in all three Guardians of the Galaxy movies and who cameos as a major DC character in Superman. “Tromeo and Juliet’s a crazy, weird movie. But it’s interesting, and he actually did it and made it and then just kind of kept going. I remember those days from just being around, whether it was in New York or when we first moved to L.A. together, that he just had this constant thirst to make something and put it out in the world.”

Eventually, Gunn wrote the scripts for 2002’s Scooby-Doo and 2004’s Dawn of the Dead and Scooby-Doo 2: Monsters Unleashed; the latter two made him the first screenwriter to have two movies open at number one in back-to-back weekends, announcing him as a franchise player. This got him the opportunity to make his directorial debut, the gory 2006 horror-comedy Slither, starring Fillion and Elizabeth Banks. “It made dozens of dollars at the box office,” he notes, “but people really liked it, and it got really good reviews. And so it was incredibly helpful to my career and getting people to be interested in hiring me.”

I think he was a maniac, but he was the best kind of maniac. You just have to keep going and keep moving. I think that in some ways, James’s superpower is that when he gets an idea, he doesn’t abandon it, he completes it, and then you’re able to move on to the next thing, and you leave a body of work in your wake rather than a bunch of unfinished projects.—Sean Gunn, who has a cameo in 'Superman,' on his brother's early work ethic

After making the low-budget and rather subversive Rainn Wilson vigilante comedy Super in 2010, Gunn eventually landed the first Guardians of the Galaxy film, as part of Marvel’s tendency to recruit filmmakers from the indie world. Based on a set of characters completely unknown to the general public and potentially too strange for mass tastes (there was a time when the world seemed unready for Groot), the 2014 film was a surprise smash, cementing Marvel’s Imperial Era and turning Gunn into a sought-after commodity, one who could inject blockbusters with irreverent humor and heartfelt empathy for the universe’s castaways.

“For the last decade or two, I think the name of the game is building these story worlds, which is why you have such massive success for shows like Game of Thrones, and James is built for that,” says Sean. “He’s not only a really good writer, but he’s a writer who has a vision for the big picture. He has always been able to keep a lot of balls in the air at the same time.”

In 2018, as he was preparing to direct Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3, Gunn was fired by Disney and canceled (to use what feels like a somewhat dated and inaccurate term) after right-wing activist Mike Cernovich (who helped spread the Pizzagate conspiracy a couple years earlier) unearthed his old tweets, which featured the sort of sophomoric, “edgy” humor best left behind in high school. While the resurfacing was a calculated effort to embarrass a high-profile progressive, the tweets, though done as a joke, were in rather poor taste, and the backlash was both real and a sign of the times.

During the online partisan boom of the Trump era, celebrities such as Ricky Gervais, Dave Chappelle, and too many others became brittle and defensive when called out for offensive jokes, doubling down and losing their artistic sensitivity in the process. Gunn went the opposite direction, listened and grew, and, as he tells it, became a more thoughtful artist in the process.

“I was haphazard with the things I put online when I was younger. When people were reading my blogs in the context of what was happening, they would see that things were satirical. But taking it out of context with just a piece of it, it could hurt someone. And I saw that, so I regretted it. I truly regretted it,” he says. “Back in that time, my brothers and I, everything was always about one-upping each other and saying the most shocking thing possible to each other. And when I was first on Twitter, I had 5,000 followers, and it was as if, you know, you can say anything you want. I’m lucky I didn’t say worse things, frankly. You can really push people’s buttons, just try to offend people. Which is not a great thing to be doing in a public context.”

As far as his firing went, he looks back and understands why it went down the way it did. “Everything culturally was just going crazy, all of a sudden it seems like everybody in the world is crying foul, and then corporations were acting immediately and firing people before due diligence. A lot of people were just really trigger-finger reacting to stuff, and I can see why,” he says. “Because when you’re being attacked online ... I mean, the piranha may not be the most popular fish in the sea, but when they’re eating you alive, they seem like they’re the only fish in the sea,” he says, reflecting on how social media firestorms seemed to have had a disproportionate impact on people’s careers and corporate decision-making in the 2010s in a way that seems less salient today. “People have now taken a step back, maybe honestly a little bit too much of a step [back], from these situations.”

After DC hired him for the 2021 reboot The Suicide Squad (another story about unloved, misunderstood misfits that Gunn accepted in lieu of offers to direct other, more well-known characters), he returned to Marvel to direct, after all, the surprisingly moving Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3.

Gunn has long said that the antisocial talking raccoon Rocket, whom the movie focuses heavily on, is the character he relates to most, and that the cast of Guardians coming to his defense was a profoundly healing moment for him.

In Vol. 3, the Guardians go on a dangerous mission to save Rocket’s life; in the process, the character (one of Bradley Cooper’s best performances, and I’m not doing a bit here) finally manages to shed the layer of sarcastic armor he’s used to protect himself from his trauma and becomes whole, a move that “1,000 percent” mirrors Gunn’s personal evolution. As the creative writing professors say, write what you know.

“For Vol 3., I almost think of the whole thing as autobiographical,” Gunn says. “Rocket was this really mean little guy who felt completely and utterly alone. I mean, that’s where I started with the whole series of Guardians of the Galaxy. When they came to me with the project, I said, ‘Well, what if Rocket is real?’ And it seemed to me that he would be the saddest creature in the universe. Frankly, I probably feel like that myself at times, as many of us do. I’m not saying that I’m unique in that respect. I have a difficulty with accepting love from the outside and was always edgy as a kid—just so edgy,” he adds, wearily. “Got into fights all the time, all that stuff. Rocket is me. I mean, that’s me.”

His brother concurs with all of this and has seen the change firsthand. “I do think that Rocket has this journey over the three movies where he goes from being somebody who doesn’t care about anything, he doesn’t give a shit, to someone who’s like, ‘Oh, I actually do care. I can make a difference. I can have a positive effect on people, and caring about other people isn’t stupid or worthless.’ James embodies that completely,” Sean says.

I’m trying to make movies that have elements to them that we’re not usually seeing. That makes them fresher. I think most movies are boring.—James Gunn

Be it superhero comics, sci-fi novels, horror films, or shows of all stripes, genre fiction has long served as a way to smuggle weighty themes, political commentary, and social critique into popular fare. After all, Superman was created by two Jewish men whose families had fled Europe and who looked at the rise of Hitler with terror. They set out to create a secular Christ figure as a therapeutic response, inventing the very idea of the superhero in the process. Gunn has long worked in this vein, a writerly interest that has only deepened in the past few years. Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3 is about healing from childhood abuse at the hands of an authority figure, Superman is unabashedly about immigration, and The Suicide Squad was so critical of the U.S.’s involvement in developing nations that it could have been cowritten by Noam Chomsky.

“I think I’m allowing a fuller picture to come into the movies that I make. I don’t want to pretend like I’m doing this to make a message. I’m not. I’m really creating these things first and foremost as pieces of entertainment. That’s it,” Gunn says, allowing that “when you’re a person who’s socially conscious—and I mean that in the most specific sense, I mean conscious of what is going on in the world and what the relationships are like around us, what politics are, all these things—you want more out of movies. I’m trying to make movies that have elements to them that we’re not usually seeing. That makes them fresher. I think most movies are boring.”

The idea of a man from Krypton who can fly and shoot lasers from his eyes and whose sole purpose is to help others is one of those fantastical ideas we’ve all gotten used to, just as we’re all getting used to the rebellious provocateur James Gunn becoming a suit and overseeing the cinematic and television futures of some of Warner Bros.’ most valuable intellectual properties. He’s still getting used to it too, he admits.

“I learned that I’m not good at the suit side of it. Peter and I, we largely split things up. I’m the boss on the creative [side]. He’s the boss in everything else. We don’t ever step on each …” He takes a second and corrects himself. “I don’t want to say don’t ever, because it could happen someday, but we haven’t ever stepped on each other’s toes. It’s not that we never have disagreements, but they’re very minor and communicated. But at first, I did go to, like, the board and the meetings and all this stuff, and it really killed me.

“So we had to reorient how we attack the job,” he adds. “And it’s been more pleasant since then, but it’s a lot, frankly; it’s a lot to be trying to write and direct. If I was just doing Superman and Creature Commandos and Peacemaker at once, that would be the most work I’ve ever done in my life. But then to also be trying to shepherd Supergirl and Lanterns to a much lesser extent, Sgt. Rock and Clayface, and all these things, it gets to be a lot. It’s a lot. And I had to learn that I can only do so much, where my time is really worth the most. And luckily, I think that works pretty well with working hard on finding the right talent and then giving them a lot of leeway, a lot of space. And if that means they screw up, that’s OK. I think that’s a strength.”

Still, there are times when the executive Gunn and the indie-born filmmaker Gunn have to do some negotiating to balance artistry and the unpleasant realities of the bottom line. Gunn and Safran have announced an ambitious slate of films, dubbed “Chapter One: Gods and Monsters,” which includes a planned adaptation of The Authority, a scabrous series created by Bryan Hitch and (the now disgraced) Warren Ellis. The popular superhero team includes the out couple Apollo and Midnighter, who shared one of the first queer kisses in superhero comics history. In recent years, as part of yet another right-wing movement, brands have been moving away from openly supporting the queer community, and China, one of the most important international markets for film studios, has long censored entertainment with LGBTQ themes, though sometimes the stringency of the censoring seems to vary. That could put Gunn and DC Studios in a difficult position, as Warner Bros. has faced headaches about this issue in its films before.

In interviews and on social media, Gunn insists that when he wrote the Scooby-Doo script, he depicted the character Velma as a lesbian, but it later got watered down by nervous executives. It’s fair to assume he would be more than up for showing Apollo and Midnighter (and other DC characters) as openly queer, but it’s also fair to wonder whether he can push that through corporate skittishness. When asked, he replies, “First of all, let me be honest: [The Authority] hasn’t been one of the projects that exactly caught fire in development.”

He elaborates: “There are realities of things like that, like if we can’t get into certain countries, you’ve got to factor that into the budget you’re making the movie for. But I think that all those types of things are completely possible.” He adds that featuring on-screen queer superheroes might require some creative approaches. “At the end of the day, we have to make movies that make money. But I don’t think that leaves very many topics off the game board.”

When Gunn and Safran began working with Warner Bros., they knew they had to leave behind the DC Extended Universe that Zack Snyder started with the 2013 film Man of Steel and that included a notably uneven (usually overly serious, sometimes awesome, and often needlessly desaturated) slate of films with some hits and plenty of misses. (Snyder departed the DCEU during the postproduction of 2017’s Justice League after the death of his daughter.) DC Comics tends to reset its continuity and start from scratch every decade or so, via large-scale crossover events such as Crisis on Infinite Earths in the ’80s or Flashpoint in the 2010s, so a cinematic reboot seems like an inherent part of DC Comics characters' DNA, whether they’re appearing in print or on the screen.

“I knew that we needed a fresh start,” Gunn says. “I was writing a Superman movie when I came into the job, and he was a Superman who was 29 years old, and that Lois was around the same”—in contrast to Amy Adams’s Lois Lane and Henry Cavill’s Superman, who were much older. Gunn insists he wouldn’t have a problem telling a story of an older Kent and Lane: “I think it could be really cool. It just wasn’t the story I was telling. I was micro-focusing on a moment in their relationship that was specific to that time. We just tried to rip off the Band-Aid as much as we could when we came in.”

Around the time that Gunn came on, Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson campaigned hard for Cavill, who hadn’t starred as Superman since Justice League underperformed in 2017, to cameo in his 2022 film Black Adam. Johnson also advocated for the two characters to face off in a sequel that was ultimately scuttled when Black Adam underperformed (though Johnson said it was due to the change in leadership), which helped make it easier for Warner Bros. to roll the dice on a new take, but not before Cavill announced his return to the role—before having to retract that announcement less than two months later.

“It was shocking. We had the job. Everybody knew what the plan was. And then all of a sudden, a week or two before we were announced, Henry Cavill thinks he’s back, which was really unfair to him,” Gunn says. “I don’t know how in the world things got so miscommunicated through so many channels. I really, really felt bad about it with Henry, because he was really a perfect gentleman and a nice guy. That whole thing was a mess. I mean, it was like this vacuum of a perceived loss of a center or power, and all of a sudden, everybody’s vying for power, not knowing that [Warner Bros. Discovery CEO] David Zaslav is just talking to me and Peter, figuring out if it’s something we can do or not.”

Snyder and Gunn worked together on the Dawn of the Dead reboot, they recently appeared together on an episode of Rick and Morty, and Gunn asked Snyder for advice when he started putting together Superman. Nevertheless, there’s been a persistent narrative, both online and in some media corners, pitting the two against each other.

It’s not the idea that ‘What if Superman were real and in our world?’ that we’ve seen before. His entry point was, ‘What if the real world was the comic book world? And we lived in that world?’ And I found that to be very new and very exciting.—Nathan Fillion, who plays Green Lantern in 'Superman'

“I don’t love it. It’s also so foolish to me because I know Zack, and we’re completely friendly. I like what Zack has done with movies. I think that Zack has done a lot of unique stuff,” Gunn says. He also bristles at the idea that he’s the lightness that represents the opposite of Snyder’s work. “That kind of bothers me, but I just let it go because that’s how people look at things. There’s plenty of darkness in my movies. It’s weird that people think they’re all fluff and light, because to me, my movies are a balance of dark and light. They’re very emotional movies. If that’s light, then I guess they’re light,” he says, before pointing to the darkness of Rocket’s trauma. “But I mean, the Guardian stories are about a character that was tortured and torn apart and put back together again endless times who watched his friends get murdered and destroyed and tortured in front of him and then cannot recover to accept any type of compassion for other human beings and/or other creatures. … I don’t think that seems like a light story.”

Even if that’s a fair assessment, it’s true that Gunn wanted to make a film about Superman because he’s a good man. Gunn believes in goodness. He thinks we need more of it. He’s seen what it can do for people, starting with himself.

“There are moments when I don’t believe that, moments of depression. … But I’ve seen a lot of kind people in my life. I’ve seen a lot of goodness. I’ve had people show me a lot of compassion as an adult, but also when I was younger. I got sober when I was very young. I still remember when I was on all sorts of chemicals, and my dad found out I sort of hit bottom. I called my father. I thought I was having a psychotic breakdown. And he’s like, ‘Jimmy, I want you to get on a plane. I’m going to have somebody come and pick you up.’ And my dad was the attorney for the Sisters of St. Joseph. He and I went to a convent.

“And here I am with this long hair, different colors, and wearing shredded clothes. … I had no body fat whatsoever. I’m probably 2 percent body fat. And I’m sitting there, this tall, gaunt, skinny guy, and I had these nuns taking care of me. And I’m like, ‘How lucky am I?’ I didn’t do anything to deserve that. If they knew what I was doing a couple of days before, would they have been treating me with kindness? I don’t know,” he says. “That’s one of the moments in my life where things were so intense. And then I have another hundred of those moments where kindness was so incredibly potent.”

That the world needs more kindness and good people might not seem like a political statement, or a controversial one, or even a profound one. But it is a true one. Gunn believes it, and he made a film about it. He hopes it resonates. But he feels a bit strange about how timely the film he made has become.

“I don’t know. I’m happy that people want to go see Superman. I’m excited about that. There’s also a sadness to that, because people want someone in their lives who’s a person in power, who’s powerful and strong, and who is looking out for everyone you know and who cares about people. Whether or not he’s always effective or not, we can trust him, he’s good,” he says. “There’s a sadness to that because we don’t really have that in our world right now, necessarily, and that’s difficult.

“But also, I think it’s not sad. It’s very positive that so many people want that,” he adds. “You can see that in the people that are excited about the movie. And I’ve seen that a lot in traveling around the world. The people who love Superman, the super Superman fans, are some of the sweetest people I’ve ever met in my life. There’s something about the character that people who are really good are attracted to.”