‘F1: The Movie’ Puts You in the Driver’s Seat. Here’s How.

Reporting live from the Canadian Grand Prix—which also happened to be a movie setTwo hours before lights out at the Canadian Grand Prix earlier this month, the Alpine team is troubleshooting. A couple of gunners are struggling to drill a tire into the rear left wheel—and while this is just practice, every hundredth of a second, and every detail, counts in Formula One. A few crew members reverse their pink-skinned car, then shove it forward again, toward dozens of waiting hands and helmets. The team crouches into position. The jack goes up. Four tires off. Four tires on. Faster.

PBBBFFTTTTT–REEEEERRRRRR … PBBBFFTTTTT–REEEEERRRRRR.

Inside the garage, electronic music scores a team of technicians scanning multiple screens of data—graphs and numbers tracking tire degradation, fuel flow, downforce, brake temps, engine performance. Mechanics hover around one car’s chassis, making final inspections. At a workstation, race team manager Rob Cherry pores over notes on strategy, hunting for advantages, considering all the variables. The air is thick with the smell of warm rubber and gasoline. It’s almost time.

Near the grid, it looks like driver Pierre Gasly is trying to disappear inside his helmet. He’s blocking out the noise—the screams of fans angling for a track view, the buzz of media and VIPs shuffling through the pit lane, the sharp gazes of investors peering down from the ritzy Paddock Club. Alpine has sputtered through the first third of the season. They sit last in the Constructor’s standings. Gasly has just 11 points through nine races, better than only six other drivers. After Alpine sidelined driver Jack Doohan earlier this season, Gasly’s new teammate, Franco Colapinto, is gunning to establish himself. The team wants a modest result: points. Finish 10th or better. But a late change to his car means that Gasly must start the race from the pit lane.

That was the only way we could have pulled this off—shooting at real races, putting Brad and Damson in real race cars, on the track, during race weekend. This is a very tightly controlled sport, and to have that sort of access was pretty unbelievable.Joseph Kosinski

“Once you get in the car, if you make the wrong calls and the wrong decisions and you don't do the right thing on track—if you don't bring the results back—then you're putting all these people at risk,” Gasly tells me.

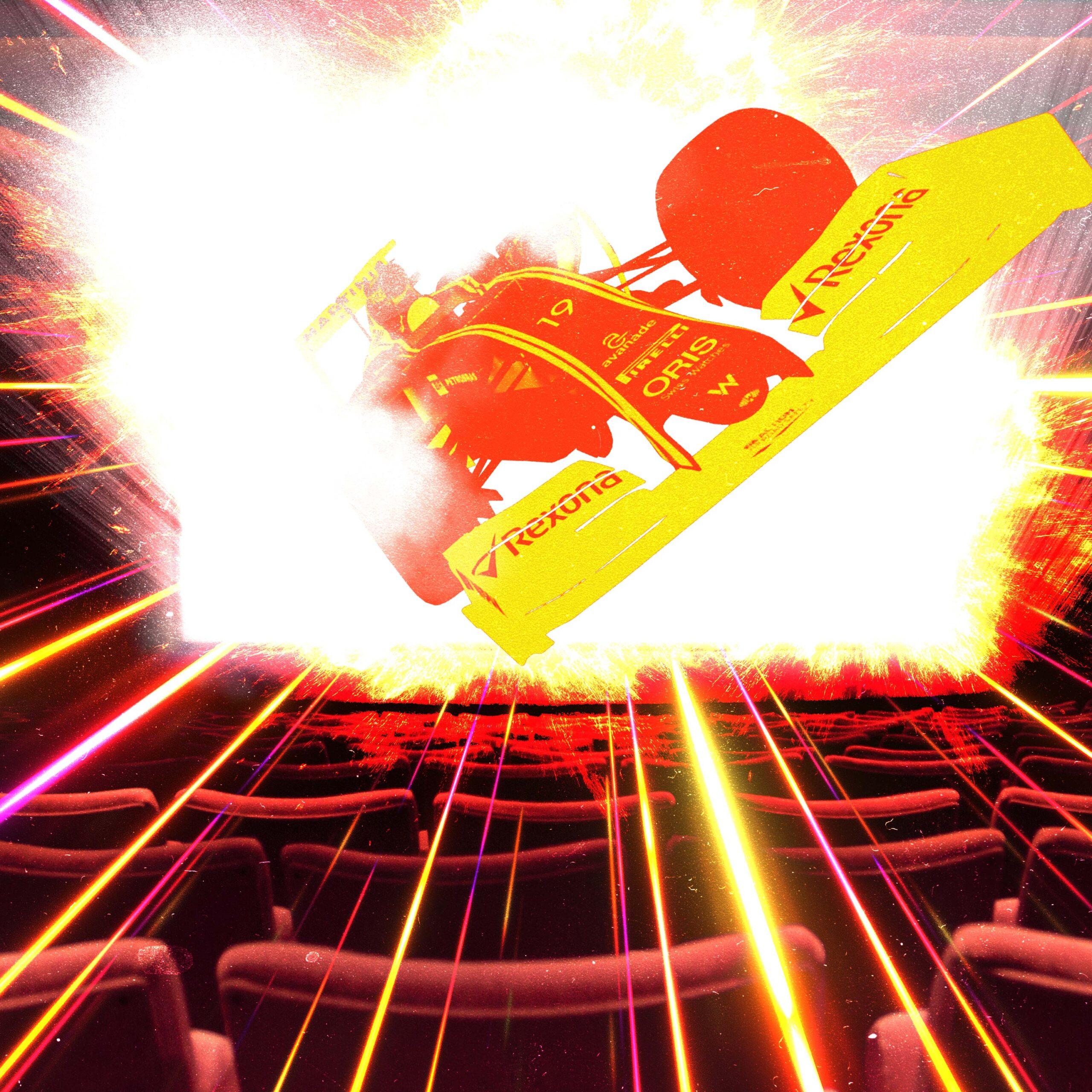

The stakes are similar in F1: The Movie. Following a yearslong hiatus after a bad crash, veteran driver Sonny Hayes (Brad Pitt) returns to the grid in the season’s twilight, agreeing to drive for the fictional last-place team APXGP. His goal? Keep the team from collapsing, save the job of its beleaguered owner (Javier Bardem), and mentor its young hotshot driver Joshua Pearce (Damson Idris). And maybe find redemption. The movie, directed by Top Gun: Maverick’s Joseph Kosinski, captures the speed, the sound, and the energy of a Formula One car. But it also pays incredibly close attention to tire strategy, driving maneuvers, g-force training, teammate drama, and the overwhelming burden of hopscotching around the globe to determine the fate of a billion-dollar enterprise.

After all, Kosinski’s goal was to create “the most authentic racing film ever,” he says—to immerse audiences in a dangerous, high-octane world of strategy, teamwork, and split-second decision-making; to put you on the track and inside the cockpit; to take you around the world.

Over three years and with a reported $300 million at their disposal, he and producer Jerry Bruckheimer went all in to achieve those goals. They brought in seven-time F1 champion Lewis Hamilton as a coproducer, they teamed up with Apple and Sony to develop specialized cameras, they put Pitt and Idris behind the wheels of retrofitted F2 cars, and they embedded the entire production into F1’s traveling circus. “This was a partnership,” Kosinski says. “That was the only way we could have pulled this off—shooting at real races, putting Brad and Damson in real race cars, on the track, during race weekend. This is a very tightly controlled sport, and to have that sort of access was pretty unbelievable.”

After Netflix’s docuseries Drive to Survive delivered F1 to America, the sport hopes that F1: The Movie can be another inflection point. But how does it stack up against Drive to Survive? How real does it feel? Within the paddock, Gasly feels uniquely qualified to answer. And while he’s quick to caution the purists (“You're not going there to see a documentary,” he says), he admits that the movie gets a lot right—the rush, the rivalries, and the feeling of this particular Sunday in Montreal.

Kosinski had always wanted to make a racing movie. He got a taste of it while directing 2010’s Tron: Legacy and nearly directed his own version of Ford v. Ferrari three years later. The closest he got was Top Gun: Maverick, a journey that satisfied his need for speed and eventually earned $1.5 billion at the box office, supplying Hollywood with its first major post-pandemic hit. Kosinski had gotten people back to theaters and put them inside an F-18. He wanted to do the same thing with a race car.

A story idea formed during the COVID-19 pandemic after Kosinski got hooked on Drive to Survive. In its first season, Netflix didn’t have inside access to the top Formula One teams, meaning that the series had to focus on the little guys nibbling for points and the long shot of a podium finish. Kosinski was fascinated by the teams’ weekly determination. “These rookies spend their whole lives, from 6 years old, trying to get to Formula One, and then they get there and they're in a slow car trying to prove they belong,” he says. “I thought that would be an interesting story and the way into this world.”

As he wrapped up Maverick in 2021, Kosinski workshopped the idea with Bruckheimer. The legendary producer hadn’t followed F1 but immediately understood the potential of giving the most popular racing series in the world the same big-screen sheen of their most recent aerial adventure. “They’re going 220 miles an hour,” Bruckheimer says. “It's really dramatic. It's exciting.” The two brainstormed. What if they could capture the story in a real F1 environment—similar to Le Mans and Grand Prix, ’60s and ’70s touchstones that were filmed at real tracks with real drivers? “The whole practical nature of this film was inspired by those classics,” Kosinski says. “You can still watch them and still marvel at the cinematography and the feeling of being there because you really were.”

But first, Kosinski needed to make sure that he’d have inside support. Around the same time, he emailed Hamilton to gauge his interest. The Mercedes (now Ferrari) driver was interested in playing a role in Maverick, but their schedules never aligned. "I want to tell a story in your world,” Kosinski wrote to him. “Will you help me?” Hamilton had been eager for another Hollywood opportunity and loved the potential of this idea. This was his chance to establish himself (and his production company, Dawn Apollo Films) in the film world, to work with Bruckheimer, to share the intricacies of his sport with a wider audience. “I was kind of able to form this dream team of producers around me,” Kosinski says.

Once Pitt agreed to star and Apple agreed to foot the bill, Kosinski began formulating a proposal for Formula One president and CEO Stefano Domenicali. The story, written by Ehren Kruger, would hinge on intra-team conflict, with no external villains. (“I think that was important to Stefano,” Kosinski says.) The loftier goal: join the F1 races, turn APXGP into “the 11th team,” and jet-set to different continents like a legitimate racing operation—all without disrupting the season. The biggest question was also the simplest: How? But Kosinski had experience selling these kinds of ambitious ideas, specifically ones that required immersive, practical shots. In Maverick, he digitally re-skinned F-18s to look like different fighter jets, a VFX technique he’d developed for an earlier car commercial. “You're getting all those things that tell you something is real, but you're using a little bit of Hollywood magic to change it,” he says.

When he and Bruckheimer eventually met Domenicali, they came prepared with a demo reel filled with similar tricks. Kosinski had taken clips from international F1 broadcast footage, highlighted a Mercedes passing across the screen, and then replayed the same car’s movement with APXGP livery instead. It showed the full potential of Kosinski’s designs and easily swayed Domenicali. “He just kind of got it right from the start and really opened doors for us,” Kosinski says. Six months later, in October of 2022, the director showed the same demo to a room of F1 team principals. Kosinski told them they’d be playing themselves in the film and, on occasion, their cars would be digitally altered to become APXGP cars. Any skepticism about how the movie might represent the sport evaporated. “It was a real insight into what they were going to bring to this production,” says Tim Bampton, F1’s official liaison between the film and the series. “That was a moment when the sport realized, ‘OK, this is very sophisticated.’”

But the pitch went beyond clever VFX. Kosinski knew that if he was going to capture the spectacle of the sport, he’d have to show it like never before. Using the camera system he’d developed for Maverick, Kosinski, a former architectural engineer, spent a year with Sony designing 25 camera prototypes—miniaturized, large-sensor lenses that could still shoot in IMAX quality. He partnered with Mercedes to construct six custom cars (“The most sophisticated vehicle ever built for shooting a movie,” Kosinski says), each capable of holding 16 stabilized camera mounts, with fiber-optic cables running into an internal battery bay inside each car’s body.

Apple helped, too. To capture cockpit POV shots, the studio developed an enhanced iPhone camera that could capture 4K raw video and fit perfectly into spaces already carved out for F1 broadcasts. Throughout the season, F1 allowed Kosinski to insert the Apple system into a few cars every race day to record the high-quality footage he desired. But the director’s greatest invention was a remote-controlled rig he created with Panavision—four cameras that could pan 180 degrees wirelessly and show both the vehicle and the driver during a race, without making any cuts. “It just gives you the sensation of really being there,” Kosinski says. “You really feel connected to the action in a way that I don't think any movie has been able to do before.”

Bruckheimer is blunter: “And also—our two leads drove those cars.”

When I meet with Colapinto, Alpine’s 22-year-old second driver, a few days before the Canadian Grand Prix, he explains the challenge of driving an F1 car. There are the mental components—the ability to shut off external thoughts, to stay on plan, to find focus in the heat of an adrenaline kick so that “you’re just driving and nothing else matters,” he says. But the physical component is just as daunting. The temperatures. The dehydration. The hand-eye coordination. And the most taxing: “You are pulling five, six g’s for two hours,” Colapinto says.

“These guys are athletes,” Cherry asserts, “and they have to be, because they wouldn't survive the race otherwise.”

Kosinski knew that it would take time to get his actors to that level, but he wasn’t exactly starting from scratch. Though Idris had hardly raced previously, Pitt had spent time on dirt bikes throughout his life and had a good feel behind the wheel (and he'd spent time go-karting with Tom Cruise on the set of Interview With a Vampire). When Hamilton first met Pitt in Los Angeles, he was impressed by the actor’s innate abilities. The F1 superstar had worked as a driving coach as a side hustle early in his career “and had some pretty bad drivers along the way [who] just didn't know where they were on track,” Hamilton says. “I could sense [Brad] really knew where the lines were.” Still, Pitt couldn’t process some of the test drives Hamilton took him on. “He's kind of like, 'Jeez, what is my body going through?’” Hamilton says.

To get both actors up to literal speed, Kosinski enlisted Luciano Bacheta, a former F2 champion, as their trainer and stunt double. Idris worked from the ground up—go-karts, simulators, and then real cars, eventually graduating to the Formula Three level, where Pitt already felt comfortable starting. They spent about three months there, adjusting to the effects of the g-force on their bodies, and then jumped into F2 cars. This was always the end goal—Mercedes had designed the movie cars to look like F1 outfits but installed less powerful F2 engines in them. That didn’t make them any easier to learn: Even though they’re less complex and physically demanding to drive, F2 cars are “not made to be your best friend,” Bacheta says.

As the actors progressed, Bacheta created more stress tests for Pitt and Idris, giving them smaller windows to warm up their tires and targeting specific lines for them to follow around the track. By the time they were shooting, he wanted no hesitation. But they faced an early hiccup. Apple executives had, according to action-vehicle supervisor Graham Kelly, mandated a 140 mph limit for the actors, a decision that ironically made things less safe. “When you brake from 110 or 100 mph, no heat is generated into the brakes because the car's not producing the downforce,” Bacheta explains. “If you can't push the brake pedal as hard, you don't generate the heat into the brakes. If you don't generate the heat into the brakes, the tires don't heat up. And if the tires don't heat up from the brake, you don't have any grip. It all has a knock-on effect.”

He and Kelly pushed back. They each wrote out five-page documents explaining temperature needs and the dangerous effects of braking at slower speeds, that the cars needed to increase their speed on turns to grip the road better. After enough protest (and enough rule breaking), the safety monitors “came to their senses,” Kelly says. Although, he admits jokingly, the first trial run without the speed constraints ended in a decent-sized crash. “It was a double-edged sword,” he says. “It also proved that the car was safe enough to have a crash.”

By the time filming kicked off at Silverstone Circuit in 2023, both actors had been through the gauntlet. Now came the harder part: blending in. Pitt didn’t want to be a spectacle. Ahead of the England-based race, he addressed all the drivers during their meeting, promising not to disrupt the rhythm of the weekend. “It’s really cool when you’ve got Brad Pitt showing up at your work,” Gasly says.

For the rest of the crew, the goal was simple: Don’t compromise the safety of the drivers, and protect the integrity of the event. “Within those two parameters, we found that a can-do mindset helps you get there,” Bampton says. That meant constant coordination with the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile as APXGP set up shop in the paddock line. The production team built garages and mock hospitality suites and worked within strict 15-minute windows—squeezing in racing scenes either before practice sessions or after qualifying. In between, Pitt went to mixed media zones, hopped on podiums for celebrations, and drove the track each morning, a daily F1 tradition. But they always ceded control when necessary. “We didn't want to step on anybody's toes and get in their way,” Kelly says.

After that first filming weekend, everything paused. The SAG-AFTRA strike shut the main production down for about a year. But the delay afforded Pitt and Idris more time in their cars and at the gym, allowed Kosinski to shoot a plethora of second-unit race footage, and provided more opportunities to strategize efficiencies and methodologies on the track. Without permission to shoot Pitt and Idris racing alongside F1 drivers, Kosinski found creative workarounds, like reskinning stunt double cars for racing scenes. “If you see Brad's face and there's a Ferrari next to him, it's just me in an APX car,” Bacheta says. “The other drivers and I would jump on our simulators and do the sequence in advance. That was the foundation, and then it would get tweaked a bit.”

Although Hamilton didn’t race in the movie (he does appear briefly a couple of times), his fingerprints are all over it. In Hungary, for example, he told Kosinski that if Pitt’s character were to fall back and potentially clip another car under a safety flag, it would happen only at Turn 6. Later, in postproduction, he worked with the sound team to make sure each gearshift matched the real thing—down to the subtle tonal shift between second and fourth gear. “It wasn't just about getting close to the camera. It was effectively like learning a dance routine in cars at all times,” Bacheta says. “But it had to be supported by everyone.”

Colapinto appreciated the dedicated approach to accuracy. The Argentinian has been racing since he was 9, but at a recent screening, he watched his sport from a new perspective. The view from the cockpit never felt more real. “You can't actually feel the speed, the gs that we are feeling in the corners, through the TV,” he says. “That's what the movie does. It brings that feeling of speed back.”

The weather has cooperated in Montreal, and the race is tight. Alpine is battling, trying to find 10ths of seconds wherever they can, but Colapinto can’t move past 12th place. Overtaking opportunities are hard to find. Cherry intermittently speaks over the radio to him and Gasly, who’s in 15th place, and advises that they stay in the pit windows of nearby opponents. In between pit stops, Alpine’s human performance coach Pete Webster walks around the garage with a Theragun, keeping his crew’s muscles activated to prevent cramps. The only drama so far? Hamilton ran over a groundhog and damaged his car floor.

Then, with four laps to go, McLaren makes a mistake. On the start-finish straightaway, neck and neck points leaders and teammates Oscar Piastri and Lando Norris drive in tandem, shrinking the gap between leader George Russell and the two cars ahead of them. But just ahead of Turn 1, Norris gambles. He pulls to the left, clips Piastri’s rear tire, and collides with the wall. Norris’s car rolls into the grass and sustains enough damage that he must retire it. The standings gap between the teammates instantly widens.

“I’m sorry,” Norris calls in over the radio. “Stupid by me.”

Something similar happens early in F1. Hayes and Pearce haven’t warmed up to each other yet. They both have their own priorities on the track, and the young gun isn’t ready to take any tips from the old guy. It eventually costs them at Silverstone when Pearce attempts a pass and spins both cars out of contention. Their conflict is what fuels the movie, and as Norris and Piastri could attest, it’s a real one. “It's the only sport in the world where your teammate is your competitor,” Bruckheimer says. “They all want to be the no. 1 driver.” That tension can be challenging at times, but it rang true for Cherry, who has moderated these issues before. “There's a lot of psychological aspects of keeping the driver in that sort of happy place,” he says. “It is part of our role to try and ensure that we remain neutral.”

Kosinski embedded other crucial aspects of F1’s DNA into the movie. He captures the pressure that pit crew members face. He shows the time and energy that technicians spend in the garage trying to find small advantages. He highlights the sport’s most familiar faces. And he devotes large swaths of the screenplay to drag reduction system and tire strategy, allowing F1 announcers Martin Brundle and David Croft to explain why a team on the ropes might decide between soft or medium tires. “There's no way that you could tell an authentic story in F1 without talking about tires,” Kosinski says. “There is a chess game going on for every team at every moment that makes this sport fascinating—and then the deeper you dive, the more you discover and the more fascinating it becomes.”

Everything that happened in the movie has happened in real life. It just hasn't happened all in two hours.Luciano Bacheta

But dig even further, and you’ll discover things that true F1 insiders might object to. Because APXGP doesn’t have a strong car, the team has to find an edge. And because this is a movie, that requires something more dramatic than achieving slightly faster lap times. Hayes pulls out a bag of tricks. He intentionally clips cars attempting to pass him, spills gravel onto the track to slow down the pack, and eventually asks the team to build his car for “combat.” Underdog stuff. Most of these maneuvers wouldn’t occur without some kind of punishment, but Kosinski was adamant about keeping the sport in a positive light: “We never wanted Sonny to cheat,” he says. “We wanted to find out: How far can you push it so that you can get right to the edge?”

In fairness, everything in F1 has a historical precedent. APXGP’s “Plan C,” created to nudge opponents and create chaos on the track, echoes the Crashgate scandal that occurred in the 2008 Singapore Grand Prix, when Renault driver Nelson Piquet Jr. claimed that his team told him to intentionally cause a wreck to give teammate Fernando Alonso a podium finish. (Alpine’s current boss and then–Renault managing director Flavio Briatore was initially given a lifetime ban for the incident, but the decision was later overturned and he was acquitted.) Later, at the rain-soaked Monza Circuit, Pearce disregards Hayes’s counsel, agrees to keep driving with his soft tires, and ends up flipping his car over a barrier during an aggressive overtake attempt. As The Athletic noted, the nearly fatal jump resembles Alex Peroni’s F3 accident there in 2019. “Everything that happened in the movie has happened in real life,” Bacheta says, before hedging: “It just hasn't happened all in two hours.”

Although a team would typically advocate for intermediate tires, which are typically used on rainy surfaces, Cherry found that the scenario had its merits. “We do probably find ourselves in that situation more than you might imagine,” he says. “It's the driver that makes the call because ultimately it's his safety. He's there; he knows what he can handle. We can advise on how the weather is, what's happening to other cars. But the driver is the one that will make that call. If he wants to stay out, he'll stay out. If he wants to box, he'll box.” Still, the airborne crash irked Gasly a bit. “They're trying to raise the stakes, the danger of this,” he says. “You don't need to go at 350 kph to actually lose your life. But because it doesn't look crazy, people think it's safe.”

There is one specific scene that Bacheta thinks toes the line well. It takes place during the final race in Abu Dhabi. With just a few laps to go, Hayes takes the lead after Pearce taps Hamilton and spins them out of first and second place. Under a red flag, the team puts four new soft tires onto Hayes’s car (available only because of the team’s poor qualification), giving him the extra jolt he needs to maintain position over his chasers. Originally, the script called for a hard tire swap, but Bacheta didn’t understand the reasoning. “We looked at it and we were like, ‘Why is he insisting on hard tires? You'd go out of the pits and you'd go slower,’” he says.

Kosinski took the feedback and switched the plotline. “If that same situation happened now and Alpine was in that position—if they were the only team with soft [tires]—they'd probably go out and win,” Bacheta says. “That was a nice way to be able to make the story work, make it believable, and not just have a situation where they win because they've decided to drive fast.”

Throughout the weekend of the Canadian Grand Prix, Bruckheimer has repeatedly told a story about a recent F1 test screening in the United States. Before the movie played, only one American audience member out of a group of 20 had watched an F1 race. After the credits rolled and the focus group reassembled, Bruckheimer then asked another question: “How many of you would like to go see a race now?” The entire group raised their hands. “This is the highest-rated movie that I've had as far as recommending it to your friends,” he says. “It was over 80 percent.” Later, Bruckheimer tells me that his wife “couldn't care less about racing, but she loves this film. And she's brutally honest.”

The anecdotes support Bruckheimer’s mission and mantra—to take a highly technical, high-stakes world and make it feel accessible to everyone. That’s similar to how F1 thought about Drive to Survive. Before it debuted on Netflix in 2019, the sport had struggled to attract younger audiences and saw its U.S. television ratings diminishing. Also: Mercedes’s long run of dominance in the driver and team standings had made the championship race feel stale. But the docuseries changed things—it offered behind-the-scenes access, humanized its drivers, and gained traction just as new teams and figures unseated Hamilton from atop the standings. “The added interest came at the right time,” Bacheta says, noting the fervor among fans following their favorite drivers. “They're outside the hotels more. They're outside restaurants. They're finding out where they play paddles. They go everywhere. That didn't used to be a thing.”

In some ways, Domenicali is hoping that those focus groups and the early feedback will be indicative of the wider population's reactions to the movie—and that F1: The Movie can bring a new generation to the sport. “We need to make sure that we are selling our foundation to capture the bigger audience,” he says. “It's an incredible opportunity that we cannot give up. That's the beauty of the next month—that will help us to grow and will help us to be even stronger for our future.”

Back in the pit lane, you can see and hear the synergy. As fans and media congregate and jockey for position around the podium to watch Russell’s trophy presentation, Don Toliver and Doja Cat’s “Lose My Mind”—the first song on the movie’s soundtrack—reverberates from the Paddock Club and parallel grandstands. Moments later, as Russell, Max Verstappen, and Kimi Antonelli douse one another in Champagne, the big screen below them broadcasts the movie’s digital poster. Pitt’s towering head might as well be celebrating with them.

A few garages down, Alpine is already packing up. No points today. Colapinto and Gasly missed the top 10 and now soak in ice baths, rehydrating quietly. The pit crew scrapes melted rubber from the tires and stacks them on metal racks. Hospitality staff disassemble their makeshift offices and dining areas. The convoy, filled with cars and equipment, will head to the airport soon. In two weeks, they’ll try again in Austria.

It’s not much consolation, but Gasly believes that the movie will help people understand what this part feels like. The pressure. The perfection. The heartbreak. The need to get over it and do it all again. “Sometimes you work so hard, but things don't come your way,” he says. That’s true today, but there’s little room to dwell on it. Another race awaits.