It’s now been just under two years since that very strange day when the twin indignities of social media and cable news began following the sudden disappearance of the Titan—a deep-sea submersible that lost contact with its support ship, Polar Prince, about 90 minutes into the sub’s descent, with five passengers onboard and only 40 hours of breathable air between them—on what was supposed to be an awesome journey to the now-113-year-old wreckage of the Titanic.

In real time, the Titan became a bleak void into which a horrified public projected its intense fears of deep water and enclosed spaces; the Titan’s passengers, who’d paid hundreds of thousands of dollars for the privilege, were surely suffering a mercilessly slow and profoundly terrifying death. The Titan would never resurface, but worrisome details about its design would emerge. The director James Cameron, who’s led dozens of dives to the Titanic over the years, would call into Anderson Cooper on CNN and righteously outline the many apparent problems with the Titan, chiefly its supposedly cutting-edge carbon fiber hull. Cameron made the failure of the Titan sound all but inevitable, and he made the sub’s captain, Stockton Rush, seem catastrophically ignorant. Others with relevant expertise would go even further; the longtime Titanic salvager G. Michael Harris would call Rush “a murderer.”

We eventually learned about the mercifully, vanishingly brief failure of the Titan. The hull cracked and collapsed. The sub was crushed, and its passengers were vaporized, instantaneously, by an unfathomable onslaught of water pressure. These failures were seemingly predictable, however, so we’re still left wondering why this mission ever commenced, why Rush was ever permitted to send a bunch of naive civilians to a watery grave. The U.S. Coast Guard, after two years of investigation, is expected to release its final report on the disaster in the coming weeks. In the meantime, Discovery and Netflix have both released documentaries about the Titan, OceanGate, and Stockton Rush.

Stockton Rush had a pitch. It’s captured in so much archival footage, and it almost always began with him telling his audience of potential investors or anyone else that he’d always wanted to be an astronaut.

Indeed, in 1984, Rush earned his bachelor’s in aerospace engineering at Princeton. “I wanted to be the first person on Mars,” he once told CBS’s David Pogue. He worked as a flight test engineer on F-15s for the McDonnell Douglas Corporation in Seattle before eventually turning his professional interest to ocean exploration. In 2009, Rush cofounded OceanGate, a deep-sea tourism company based in Everett, Washington. He bought the five-person submersible Antipodes to run tours from Southern California and South Florida. Rush then spent the better part of a decade developing a lightweight, low-cost submersible, with a carbon fiber hull, to transport well-paying tourists to the Titanic.

Discovery’s Implosion: The Titanic Sub Disaster and Netflix’s Titan: The OceanGate Submersible Disaster both show abundant footage of Rush and his engineers in Everett, the Bahamas, and Newfoundland hard at work developing the Titan. Both documentaries also feature plenty of audio clips of the loud, distressing pops and cracks that would constantly ring from the sub’s hull. These fissures hinted, rather unsubtly, at the gradual failure of the carbon fiber. The Titan could withstand a few deep dives but couldn’t reliably transport passengers at great depths; the Titan was, effectively, a disposable sub that would’ve ideally been piloted remotely. Even the relatively successful test dives to the Titanic and the Andrea Doria were filled with red flags—the reddest being those awful sounds that Rush would constantly downplay to his engineers as a perfectly natural byproduct of normal operations.

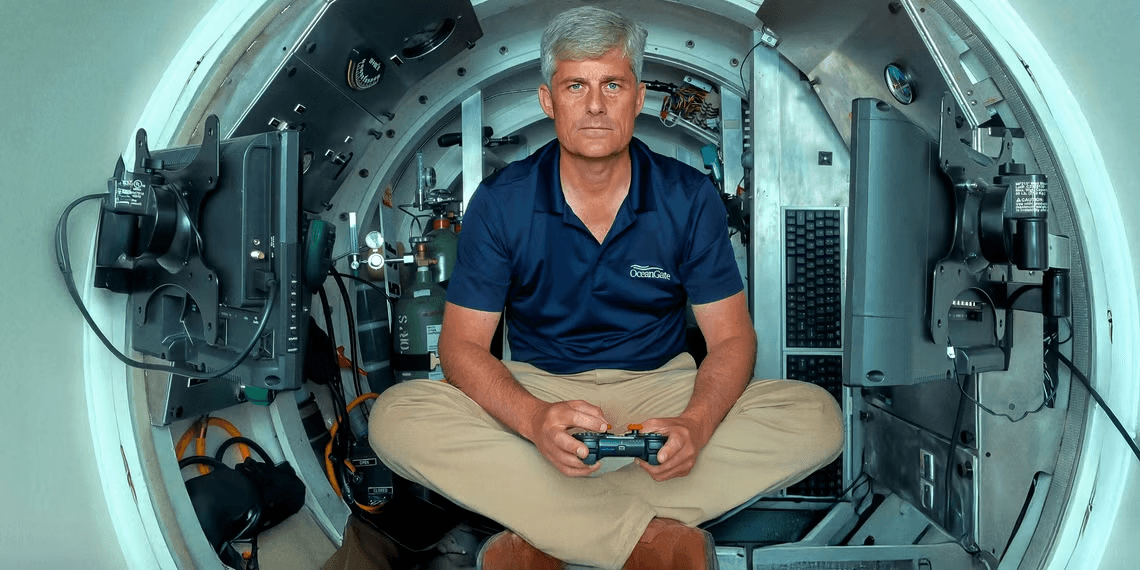

Rush was an otherwise mild-mannered caricature of a classically clueless libertarian millionaire who evaded safety regulations and independent inspections of the Titan. Rush defied his own engineers, who repeatedly warned him that his carbon fiber hull wasn’t fit for this purpose; that every major component of the sub, really, was defective in one way or another. Rush cut costs and corners to deliver a submersible that could at least theoretically turn a profit from high-dollar tourism; he insisted on the hull being a cylinder, rather than an inherently more resilient sphere, so that he could seat more passengers. Rush misapplied his background in aerospace, where carbon fiber has more practical applications, to justify his faulty designs. He hoped to be heralded as an innovator in deep-sea exploration. Behold, his indelible portrait: Rush sitting cross-legged in the hull, piloting his supposedly cutting-edge submersible with an old, notoriously crappy video game controller—a customized F710 from Logitech.

In so much of the archival footage, Rush is a restless pitchman. He’s affable enough on camera, pitching the Titan in TV news segments to Discovery’s Josh Gates (featured in Discovery’s Implosion) and CBS’s David Pogue (in Netflix’s Titan). Gates and Pogue are now speaking with the benefit of hindsight, of course, but both hosts recall Rush’s demonstrations of the Titan as a series of glitches and hitches and ominous resets and half-assed reassurances; Gates, in fact, was so skeptical of Rush and so spooked by his hours aboard the sub that he ultimately spiked his episode of Expedition Unknown about OceanGate and the Titan.

Rush was apparently far less approachable as a boss. David Lochridge, the former marine operations director for OceanGate, recounts (in Netflix’s Titan) Rush saying he’d spare no expense “to ruin a life” to prevent any of his employees from publicizing problems with the Titan. Indeed, OceanGate fired Lochridge and later sued him for breaching confidentiality so the company could stifle a whistleblower complaint Lochridge had made to the federal government’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Rush also fired his engineering director, Tony Nissen—who once told Rush, about the Titan, “I’m not getting in it”—to further deflect concerns about the sub’s design. Some subordinates were shoved out. Others were scared away. Netflix’s Titan helpfully presents an org chart for OceanGate. Throughout the documentary, Lochridge and others are ruthlessly grayed out by Rush, until he’s the last man standing.

It seemed like Rush thought he was some combination of Musk and Magellan. If his community of experts had nothing but reservations about his grand project, Rush hoped that the naive observer might mistake him for a visionary explorer. And we may well have—if not for him getting four other people, including a teenager, killed. Rush covered his “experimental submersible” in legal disclaimers but then also ran around telling anyone who might buy a ticket that the round trip was “safer than flying in a helicopter or even scuba diving.” So many of his own employees could—and did, repeatedly—highlight the faults and demonstrate the risks to Rush. He could not have undertaken a deep-sea mission any more grim and foolish.

There’s only so much closure to be found in all the subsequent documentaries and lawsuits. A year after the disaster, Cameron gave an extensive interview to 60 Minutes Australia, summarizing such scientific ignorance and so many technical errors with cool clarity. “These guys broke the rules. It’s that simple,” Cameron said. Lochridge and Nissen, with some understandable interest in protecting their reputations, try to clarify in their interviews that “these guys” were really, mainly, Rush. The sources featured in both documentaries all sound so exasperated recounting the adventures of Stockton Rush, a man who couldn’t be told anything, an innovator who thought he could simply talk over the deafening cracks in his design, an explorer who believed so strongly in his flawed creation that he went down with it—along with several others—in the shadow of the Titanic.