Search Brian Wilson’s childhood home on Street View, and you’ll see a freeway. It’s all gone now, the place where Brian and his younger brothers, Carl and Dennis, first became the Beach Boys in 1961 and wrote the almost painfully innocent “Surfin’,” starting the process of reworking the possibilities of pop music. What stands today at 3701 W. 119th Street is a mild brick structure embossed with a depiction of the band made out of cement just like the highway that cuts through the landscape above.

In the 1980s, the Beach Boys’s former home was razed along with many others in order to build the 105, a monstrous feat of civil engineering that’s become a secondhand symbolic placeholder for the comical level of sprawl that L.A. freeways can encompass. In Speed, the 105 is the freeway where they have to jump the bus; in La La Land, it’s where the opening traffic-jam dance sequence was filmed; in Season 2 of True Detective, it’s juxtaposed with the intro’s title card to—quite effectively—communicate a latent doom. To have arguably the most important residential location in the area’s musical history turned into that is more than a little on the nose, even for L.A.

The obituaries for Brian Wilson, who died this week at 82, mostly refer to him as having been from Hawthorne, which is undoubtedly an important specification. Hawthorne—named after the writer Nathaniel Hawthorne, if you can believe it—has its own character, history, people; like many suburban enclaves in Southern California, Hawthorne is a place where residents will spend their whole lives without leaving it all that much.

But don’t get it twisted: Wilson was an Angeleno. L.A. is broken into sporadic chunks, with certain areas operating as their own technical municipalities, like Santa Monica or Glendale; you’ll mostly notice that you’re in a “new” city only because the street signs change font. Hawthorne is a distinct city, sure, but in the context of the L.A. region, that distinction is a little arbitrary. Everything within modest driving distance of the Hollywood sign is all part of the same beast. The Beach Boys built musical shrines to the freedom bestowed by a full tank of gas and an open road in songs like “I Get Around,” but after helping to popularize that lifestyle, it eventually rotted their own little city from within. Hawthorne, a community by the airport that was built up by car culture and subsequently torn apart by it, is actually peak L.A.

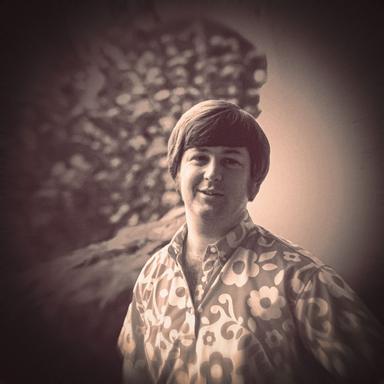

It feels appropriate that Wilson, who was just a few days shy of his 83rd birthday, was born in the summer and died in the summer. For someone like him—for the modern pop-music industry that he helped create—the summer was eternal, even when he wanted it to stop. People have long held Wilson almost accountable for propping up the endless summer mindset; it’s a long-running joke and often a dig that he never learned how to surf, as if he was somehow aping the Southern California lifestyle—cosplaying as some tanned beach-hound. In 1976, Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi actually found him in violation of the California Catch-a-Wave Statute and forced him to leave his bed and hit the waves.

But it’s not like Wilson was some homebody fresh off a bus from Kansas, either. He was his high school’s golden-boy quarterback—in band photos, he and Mike Love are always towering over the rest of the group—and had an almost religious relationship to water and the ocean, which was, indeed, just a short drive away from Hawthorne.

“He loved crazy physical things,” Van Dyke Parks, Wilson’s primary collaborator on the Smile project, told Rolling Stone in 1971, “like putting a circular slide from the roof of his house to the swimming pool, doing crazy dives. Almost adolescent stuff, but totally open: Forget who you are, what your image is, how groovy you’re supposed to be, and just have a good time. Sounds like crazy stuff, but boy, is it free.”

After Wilson moved to the ritzy L.A. neighborhood of Bel Air—painting his house purple, pissing off his rich neighbors in the process—he went to absurd lengths to bring the beach with him, having a massive sandpit installed in the house for his piano to sit upon. He liked to wiggle his toes in his synthetic beach as he wrote overwhelmingly existential songs like “’Til I Die,” which was largely about the ocean and its disturbing vastness—about all of our insignificance as we splash around in its wake, about how we’re just a speck of a speck of a speck in the scheme of the universe’s grand composition. “I’m a cork on the ocean,” Wilson sings with helplessness, “floating over the raging sea.”

“I struggled at the piano,” Wilson later said of writing “’Til I Die,” “experimenting with rhythms and chord changes, trying to emulate in sound the ocean’s shifting tides and moods as well as its sheer enormity. I wanted the music to reflect the loneliness of floating a raft in the middle of the Pacific. I wanted each note to sound as if it was disappearing into the hugeness of the universe.”

Parks said he hated that damn piano sandbox, because Wilson’s dogs would shit in it. But that didn’t stop him from understanding that the beach was, and always would be, the true identity of the Beach Boys—even if the band had tired of the perception. “They’ve been trying to get away from the beach,” Parks remarked in that same 1971 Rolling Stone story. “They don’t like their image. Even when I first ran into ’em I could never figure out why. What’s wrong with it? Get ’em down to the beach. Put ’em into the trunks. The beach ain’t bad. The ocean is the repository of the entire human condition—the pollution, the solution.”

What Parks understood was that the beach, particularly as it was channeled by Wilson, is not an inherently sunny and cheerful place. It is often quite nice. But sometimes it storms, sometimes the sea rages dangerously. Dennis eventually died in the ocean, drowning after he jumped in during a day of drinking. And even when you live in a place where the weather is pleasant 350 days out of the year, you run the risk of getting lost in a sort of timelessness. Every season can feel the same in L.A., which leads to an aimless emotional state if you’re not careful. Too much sun is dangerous—it can make you start to lose your grip on reality.

It’s easy to scoff at the supposed darkness of a rock-star lifestyle—of the trials that are somehow supposed to dwarf the riches that come from having four no. 1 hits by the time you’re 24 years old. But the ’60s in L.A. were not a peaceful party of a decade, no matter how musicians like the Beach Boys made it sound on the radio. Wilson himself had a brush with the most fetid side of his city and generation at large when Dennis introduced Charles Manson to the group, even going so far as to have them adapt one of Manson’s songs, “Cease to Exist,” for the 1969 album 20/20. Manson, who wasn’t formally credited on the song “Never Learn Not to Love,” was furious about his lyrics being changed, and left a bullet sitting on Dennis’s bed. When Manson sent members of his “family” to murder the occupants of 10050 Cielo Drive, it was a message of sorts to Terry Melcher, the home’s owner and a Beach Boys collaborator.

As he juggled the responsibilities of being a happy bandleader with the psychic chaos of living within the twisted focal point of the entertainment industry, Wilson had to be hospitalized numerous times in the ’60s and ’70s for mental breakdowns. As the contradictions mounted up, they began to swallow him. He was deeply moved by the notion of being a part of something bigger—of being “a leaf on a windy day”—and yet he was fiercely competitive, easily hurt by anything less than a perfect reception to his music. (When “Heroes and Villains,” which cost a fortune to produce and took an army to make, was shrugged at by listeners and critics, Wilson retreated to his bedroom in despair.)

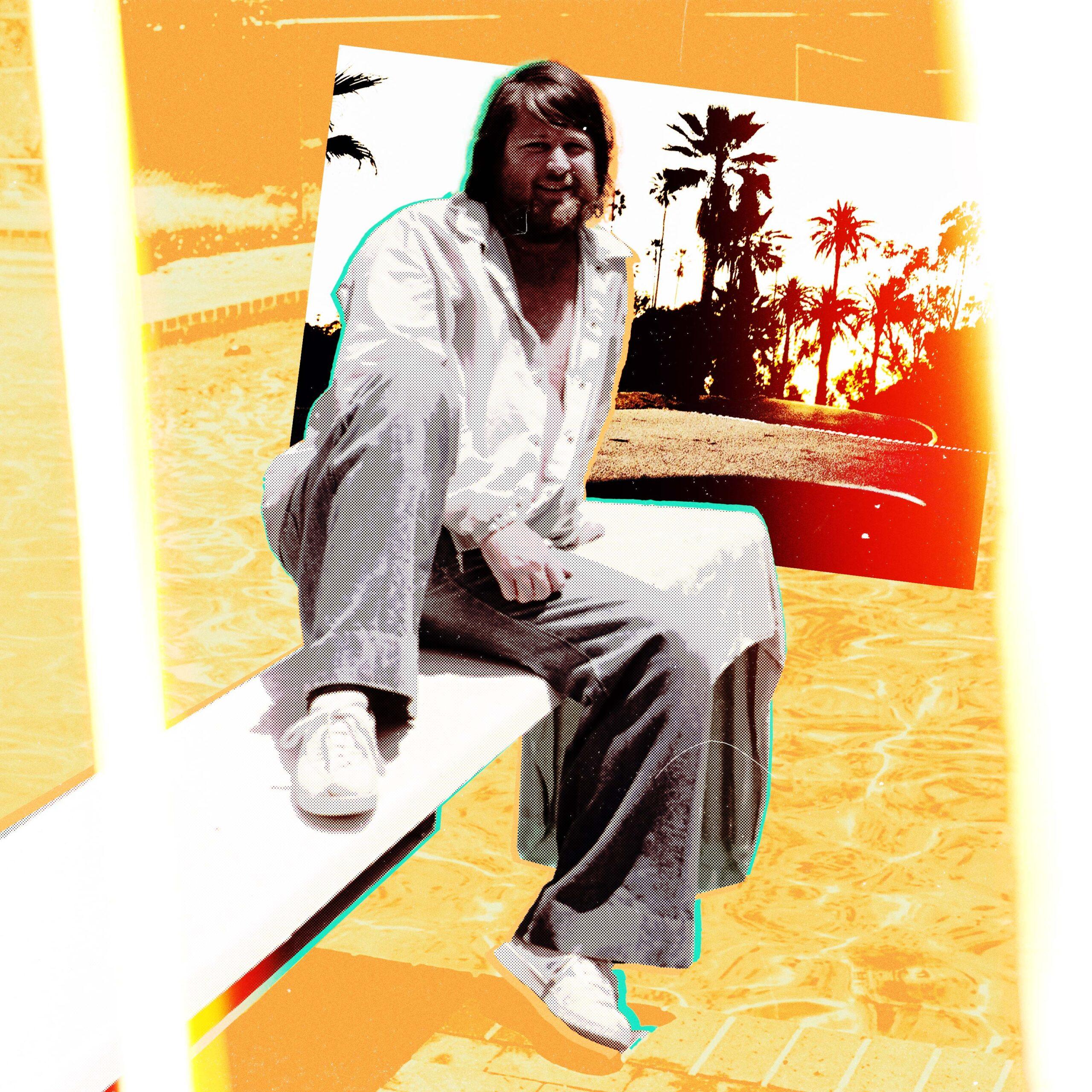

Wilson opened a health food store in West Hollywood, the Radiant Radish, but also binged on junk food, at one point reaching over 300 pounds. (The Radiant Radish, which did not have reliable hours, staff, or overhead lighting, opened in 1969 and closed just a year later.) He idolized Phil Spector, but also thought at one point that Spector was trying to kill him. (Knowing what we do now about Spector, how paranoid was that, really?) At his lowest, Wilson was often seen staggering around Los Angeles in a bathrobe, like some kind of proto-Lebowski, halfway between a beggar and a king.

The sound that Wilson developed of course led with the beauty of the L.A. landscape, and the shiny, happy people who shared space with him, on little Hondas, on sloops in the harbor. And to the people who don’t like the Beach Boys, that’s likely all they hear. Corny, naive, childish babble. But what elevated Wilson’s music beyond tourism advertisement and captured something eternal about the complexity of the human experiment was the fear and anxiety bubbling beneath the paradise—the terrible hopelessness of a song like “Please Let Me Wonder,” in which the most one can ask for is the delusional belief that things might turn out OK one day.

Wilson eventually found a way to settle the constant chop in his emotions, though he initially felt it cost him his creative ability. “I have writer’s block,” he told The Guardian in 2002. “I haven’t been able to write anything for three years. I think I need the demons in order to write, but the demons have gone. It bothers me a lot. I’ve tried and tried, but I just can’t seem to find a melody.”

The melodies would soon come back, for one reason or another, good or bad. In 2008, Wilson released That Lucky Old Sun, which includes the song “Southern California,” an autobiographical paean to the beaches and freeways that made the Beach Boys. “Love songs, pretty girls,” he sings, “Didn’t want it to end.” The song’s finale is a snippet of Wilson singing a song from his youth, Frankie Laine’s 1949 no. 1 hit, “Lucky Old Sun”: “Roll around heaven all day / Lucky old sun / Roll around heaven all day.” There doesn’t seem to be any second guess on Wilson’s part about how nice it feels.