Watching Too Much TV Can Rot Your Brain. Or Lead to the Creation of ‘The Simpsons.’

In the first chapter of his soon-to-be-released book, ‘Stupid TV, Be More Funny: How the Golden Era of “The Simpsons” Changed Television—and America—Forever,’ Alan Siegel traces the many influences of the show’s writing staff

The following is the first chapter from Stupid TV, Be More Funny: How the Golden Era of “The Simpsons” Changed Television—and America—Forever. The book comes out on June 10, published on the Ringer imprint of Grand Central.

George Meyer spent his childhood in front of the television. He grew up in the ’60s and ’70s, when TV was sucking up American attention spans like an unchecked blob. By then, ABC, CBS, and NBC had become a three-headed monster. The major networks were where people went for sports, sitcoms, and news. They’d started to trust what they saw on the tube. As frequent Simpsons target Richard Nixon once said, “The American people don’t believe anything’s real until they see it on television.”

Back then, Meyer and his seven siblings weren’t paying attention to how the rise of TV was affecting their brains. They just needed something to do that wasn’t a logistical nightmare. So they tuned in. To everything. For them, it wasn’t really even entertainment. It was a mirror world that taught them things about the real one.

“I watched so much and from such an early age, in fact, that I didn’t understand what TV was for,” Meyer said in a 2000 interview with the New Yorker. “I say this to people and they think I’m kidding, but I didn’t realize that The Dick Van Dyke Show was supposed to be funny. I thought you just watched it. The people said things, and they moved around, and you just waited till you saw the kid—you know, you liked to see Richie. My brothers and sisters and I rarely laughed at anything we watched. We watched more to learn what the world was like and how adults interacted, and what a cocktail party was, what a night club was, what you did on a sea cruise—although I did like shows where the joke would be that somebody got shot or fell out of a window. When you’re a kid, you like to see adults getting away with stuff, because you hope to join them one day in anarchy and mayhem.”

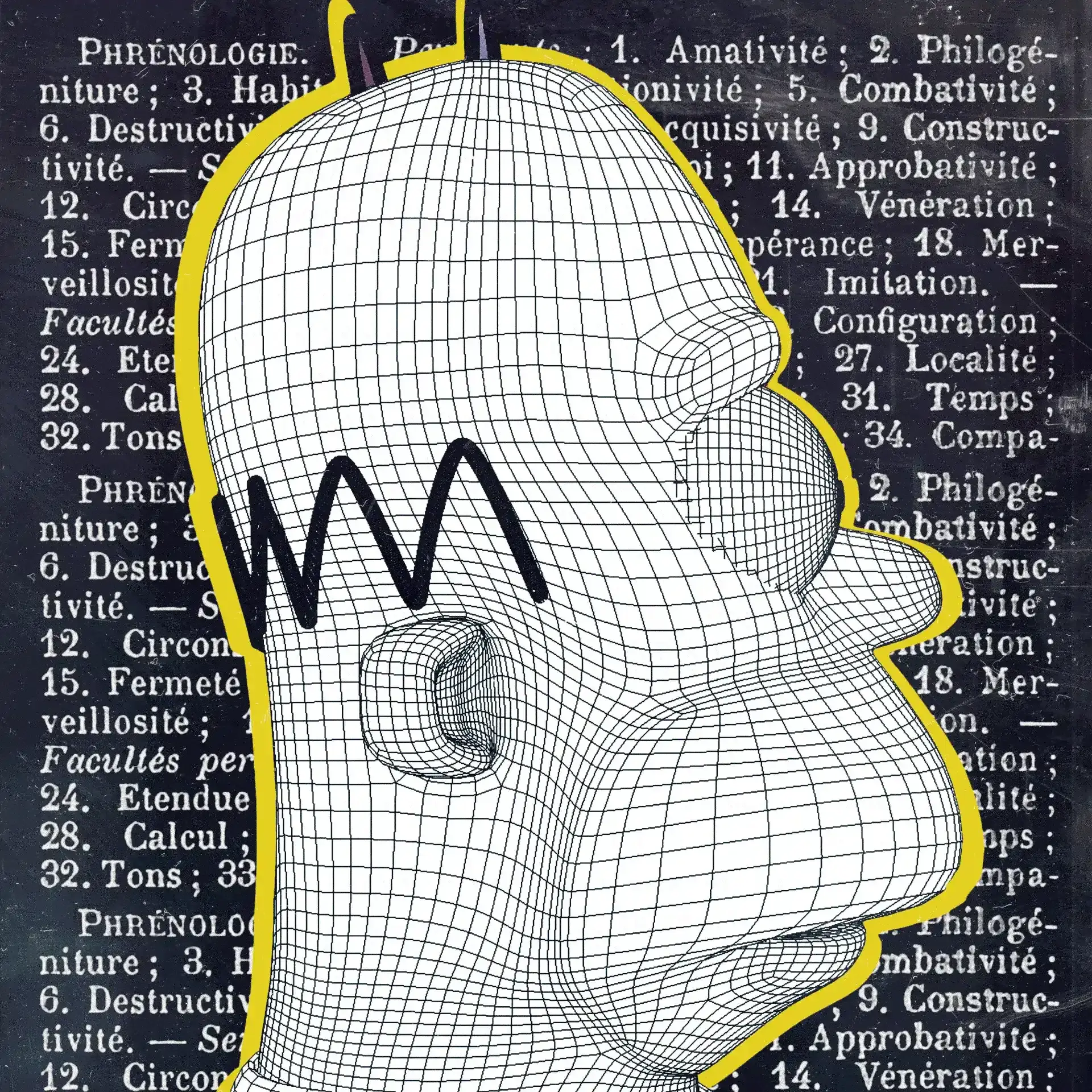

At some point, in hopes of improving picture quality, Meyer’s parents bought an antenna. “It spun around on the roof. You turned a dial and it went, ‘MMMMMMM,’” he tells me, making a humming noise. “And then the show that had been all fuzzy and snowy and double-imaged, it would kind of round into focus. And that was almost like a magical process.”

It was hard for Meyer not to be influenced by what he saw, no matter what was on the screen. There was something magical about that box. It had a hold on Meyer. And it had a hold on the other original Simpsons writers. When they were young, it activated something in them. Something that took them decades to understand and then harness. After reaching adulthood, they realized that their television-addled minds could actually be a force for good.

That’s the thing about TV: watching too much as a kid might rot your brain. Or lead to the creation of The Simpsons.

In their formative years, the future writers of The Simpsons didn’t always grasp everything they saw on the tube. But that made them more curious about what they were watching. Jon Vitti remembers fellow writer John Swartzwelder saying he loved when a show did something he didn’t understand. “It was like, ‘Wow, that’s grown-up stuff,’” Vitti recalls. “It was exciting.”

They knew all the tropes, all the clichés, all the one-dimensional archetypes that became staples in even the popular midcentury TV shows and persisted for a long time—the defining features of traditional network programming. The mostly strife-free families, the regressive marital dynamics, the too-precocious kids who leaned on catchphrases, the cookie-cutter episodes that ended tidily every week, and the ridiculous plotlines that seemed to come out of nowhere when there were no better ideas. Series like My Three Sons, Leave It to Beaver, and Dennis the Menace were often funny and inoffensive, but they had no teeth.

“The function of network TV is to make people feel that everything is OK,” Sopranos creator David Chase once said, “and they should buy the product that we’re selling during the commercials.”

As they got older, the budding comedy writers learned to separate the good stuff from the bad. “All of us had been disenchanted with regular TV and had various grievances,” Meyer says. “I would say we felt that the aims of regular TV were not ambitious enough. They just aimed to ingratiate and entertain.”

One exception was Batman. The nerdy guys who went on to write for The Simpsons adored it. And not Tim Burton’s brooding 1989 blockbuster. I’m talking about the ’60s TV show. “The basic hybrid that creates The Simpsons is Batman crossed with actual emotional stories of The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” Vitti says. At once exciting, absurd, and deeply tongue-in-cheek, the superhero series was heavily shaped by screenwriter Lorenzo Semple.

“He didn’t create the characters, but he did create the sensibility,” says Meyer, whose longtime partner was author Maria Semple, Lorenzo’s daughter. “He had an incredible eye for what kind of camp sensibility would work on television.”

Batman starred a deadpan Adam West as the Caped Crusader and featured a variety of goofy villains, gadgets, cliffhangers, self-serious narration, and fight scenes punctuated by exclamations like “WHAMM!” and “KAPOW!” The Simpsons writers revered West, who they eventually enlisted to play himself in an episode.

“All of us who were there when he recorded for The Simpsons—it was like we were in church,” Meyer says. “I mean, just to look at this guy. Talk about nailing a part of a lifetime. That was his role. That’s what he was born to do. And I love when that happens.”

Before he was a late-night TV host, Conan O’Brien was a Simpsons writer. In the ’90s, he and Robert Smigel co-created an NBC show for West about a former action hero who foolishly thinks he can solve real-life crimes. They shot the first episode of Lookwell, but it never became a series. “We cut our teeth on Batman and that’s why Robert Smigel and I ended up writing a pilot just to bring Adam West back to TV,” O’Brien once told me. “That’s how devoted we were.”

To O’Brien, Batman worked on two levels. The first, he told me, “is just an action-adventure TV show, and it delivers. It’s a home run because there’s fight scenes and bad guys and great costumes and outrageous traps and excitement and thrills and chills. ‘Batman’s in trouble, I hope he gets out of it.’ We all watched it on that level.”

“All of us had been disenchanted with regular TV and had various grievances. I would say we felt that the aims of regular TV were not ambitious enough.”George Meyer

But O’Brien eventually began to see Batman in a different light. “The ’70s roll around and you keep watching it, you start to realize—and now I’m 14, 15, 16—this is hilarious,” O’Brien said. “These scripts by Lorenzo Semple are amazing. It’s the perfect writing meeting the perfect actor. Adam West is killing it. The tone is perfect.”

Meyer had a similar epiphany when he noticed that the two most reasonable voices of Batman, Commissioner Gordon and Chief O’Hara, were kind of clueless. “It was a satirical show in that it took on authority and made authority figures look kind of ridiculous,” he says. “And the criminals were even more ridiculous. I mean, they’re carrying around umbrellas.” (As weapons, not to stay dry.)

When Meyer was a kid, the most alluring thing about Batman was that it was totally off the wall. “The rules seemed to have been tossed out the window, and that was such an exhilarating experience for a young viewer,” he says. “Because a lot of the shows, as well done as they were before that, seemed kind of square and stale and tame compared to that.”

The Simpsons, I should point out, is not a clone of Batman. The ’60s superhero show was, in truth, only one strain of influence. Each of the writers had a unique sensibility, but for better or worse, they had similar points of view. They were a group of straight white guys. Over the years, the show has been correctly described as subversive, progressive, and groundbreaking, but the makeup of the staff was absolutely of its time. Back then, that’s who shaped TV comedy. This also meant that many of their favorite pop culture references and influences were shared.

“We brought a lot of stuff to the table,” Simpsons writer Jay Kogen says. More than any other show that came before it, The Simpsons was the product of mass media. It was an elevated mix of all the stuff the writers saw as kids, from the madcap brilliance of Looney Tunes, to the silly farce Gilligan’s Island, to the traditional Dick Van Dyke Show, to the working-class comedy of The Honeymooners, to the spy parody Get Smart, to the kitschy family comedy The Brady Bunch, to the biting satire All in the Family, to the socially conscious and emotionally resonant Mary Tyler Moore Show, to the groundbreaking sketch fest Saturday Night Live.

Long before streaming gave kids push-button access to any TV show or movie that they were curious about, pop culture was far less accessible. Future Simpsons writers had to work to find new stuff. And whatever they got their hands on, they devoured.

As a boy, Kogen read Mad magazine religiously. It mixed zany jokes and sharp satire and appealed to the same kind of kids that later got into The Simpsons. “I see a really direct line between The Simpsons and Mad magazine,” Kogen says. The Mad philosophy was pretty simple. “What can we make a joke about?” Kogen says. “That’s exactly how Mad magazine approached everything. They seem like culture warriors, but really they were just like, ‘What could be funny?’”

That included lots of political satire and cartoons by artists like Don Martin and Sergio Aragonés. There was a mix of high- and low-brow humor, though Kogen wasn’t scouring issues for social commentary. “Sometimes Mad magazine takes itself seriously and tries to talk about ecology,” he says. “And when they did that, it was sort of like, ‘Oh, OK.’ But that’s not why I read Mad magazine. I would laugh at the silly drawings in the margins.”

Mad also featured Mort Drucker’s illustrated parodies, in which he, frame by frame, meticulously recreated—and made fun of—blockbusters. “I used to read parodies of movies I’d never seen,” said Kogen, whose father, Arnie, wrote for Mad. “And then later I would see the actual movie and go, ‘That’s what the parody was about.’”

In the late ’80s, Mad was still very much alive. But the bulk of the counterculture movement of the writers’ youth was long dead. They’d lived through the tail end of the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War, and Watergate. The rage and upheaval that spilled over into the ’60s and ’70s led to a strain of nihilistic irreverence that started to run through pop culture. SNL, National Lampoon magazine, and New Hollywood films—starting with Easy Rider in 1969—briefly captured the country’s general distrust of authority. But that era didn’t last.

When Ronald Reagan was elected president in 1980, he effectively pulled mainstream pop culture to the right with him. The Cold War was very much still on. With anti-Soviet sentiment peaking, jingoistic action movies ruled the box office. Pop stars, even the supposedly edgy ones, became ultra-profitable corporations that used MTV to promote their product. And TV shows started to reflect the fact that hippies had aged into yuppies. One of the most beloved TV characters of the decade was Alex P. Keaton on Family Ties, a money-obsessed Republican teenager.

Even worse, sitcoms were still relying on cute kids (and sometimes quirky adults) to repeat catchphrases for cheap laughs and “aww!” moments. Think: lovable nerd Steve Urkel asking, “Did I do that?” on Family Matters or young Michelle Tanner saying, “You got it, dude!” on Full House.

Because of conventions like that, Meyer had long before developed an aversion to TV comedy. It had been stripped of originality—if it ever had it at all. Sitcoms didn’t just bore him. They offended him. And millions of people still regularly watched! “The audience proved its own tyranny by laughing at stuff that wasn’t that good,” Meyer says. “You know, cackling at the 10 millionth time when a character would say a catchphrase.”

Even most good live-action shows seemed stuck in one location, and because of that, the past. Meyer remembers visiting the set of a traditional sitcom. He didn’t like that almost every scene was confined to small rooms. The action only rarely spilled out into the outside world, where real life happened. Just thinking about writing for shows like that made him feel creatively claustrophobic.

“They were just stuck in this little snow globe,” Meyer says. In the world of empty kids’ cartoons and cookie-cutter comedies, he wanted to make something that would, at the very least, smash through TV’s little snow globe. He just wasn’t sure who would let him take a hammer to the glass.

There were funny mainstream sitcoms, but none that quite matched Meyer’s anarchic sense of humor. And there was no sign that the American public was clamoring for something more experimental. Something like, say, a cartoon. That kind of thing wasn’t exactly trendy.

“The audience proved its own tyranny by laughing at stuff that wasn’t that good.”Meyer

The genre was pretty much dead. There hadn’t been a hit primetime animated series since Stone Age family comedy The Flintstones went off the air in 1966. Network executives didn’t want to even try such a thing. “The old guard looked at it like, ‘Oh, it’s just cartoons.’ Or, ‘It’s for children,’” says Rich Moore, an early Simpsons animator who went on to codirect the Academy Award-winning Zootopia.

Saturday morning cartoons were homogenous fluff. Most were shot from the same static perspective. “There were lots of cheap tricks that studios would use to make things simpler,” Moore says. “This is gonna sound really weird, but it’s like they would never show a ceiling in a shot, because that means you’re putting the camera low.” Characters like Scooby-Doo, you see, were hard to draw from that angle. “So you’re never gonna drop the camera low,” Moore says. “You’re always gonna keep it right at eye level, because then you’re tracing off the model sheet.”

For young animators like Moore, there weren’t very many opportunities to do cutting-edge work. Future computer animation juggernaut Pixar was brand-new. The Disney Animation Renaissance—which led to classics like The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, and The Lion King—was just starting. And inventive cartoon/live-action hybrids like Who Framed Roger Rabbit? were few and far between. “At the time, well, it was He-Man and My Little Pony,” Moore says. “And they were long, glorified commercials for toys and breakfast cereals.”

And it wasn’t just animation. As a whole, television needed a jolt. Young viewers felt like Homer, who would one day be so exasperatedly bored with what he was watching that he started smashing the family set with his fist. “Stupid TV,” he yells at the screen, “be more funny!”

Up-and-coming comedy writers could feel it, too. They yearned to make a sitcom that did more than just provide background noise. The kind of show that they loved growing up but was all too rare. A show that played with and occasionally even blew up conventions. A show that practiced anti-intellectual intellectualism—one that was smart but didn’t take itself too seriously. A show that was like nothing else on TV.

“We wanted to go a step farther and we wanted to have our own stance about life,” Meyer says. “Which is that it’s absurd, and punishing, and undignified. But it might be worth living.”

Excerpted from the book Stupid TV, Be More Funny by Alan Siegel. Copyright © 2025 by Alan Siegel. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.