At the top of the second of four acts, Wes Anderson’s new biblical espionage flick, The Phoenician Scheme, splits open its manicured artifice and spills out its textual guts. A sinner asks a nun how to get God on his side. The former is the latter’s father—though there’s more than a little doubt about that. A proper Andersonian fable, our protagonists sit aboard a well-furnished mid-century private jet, and the visual provisions include a tobacco pipe and a gifted, “secular” rosary bedecked with diamonds and jade.

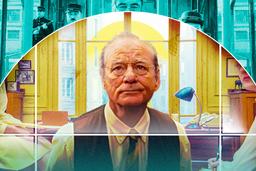

The dad’s name is Anatole “Zsa-Zsa” Korda (Benicio del Toro); the purported daughter/abbess is Liesl (Mia Threapleton). Zsa-Zsa is a friendless, seedy, philandering oligarch. Type to keep plans for orchestrated famines, outstanding slave-labor projects, and pending real-estate moves in labeled shoeboxes. Rumors abound as to whether he killed his three ex-wives; he strenuously denies ever murdering anyone “by my own hand.”

After his most recent dance with death—Zsa-Zsa’s got a knack for surviving aeronautic assassination attempts—the tycoon appears to be losing it. His brain is damaged and he’s seen visions of his own judgment day. Hidden forces are trying to squeeze him out of the international marketplace. The price of bashable rivets is through the roof. At the bottom of Act 1, he puts all of his financial hopes on a novice royal prince’s half-court heave (as in, like, pickup hoops in a subterranean rail tunnel). The shot swishes through after Liesl prays. By the time they make it to the plane, Zsa-Zsa wants to know what she said.

“It’s not witchcraft,” his daughter explains. The specifics of the plea aren’t the point. “What matters,” says Liesl, “is the sincerity of your devotion.”

Zsa-Zsa looks forward. He nods his head. To no one in particular, but everyone in a theater, he says twice: “That’s it.”

Blink and you’ll miss it on your first go-round with the movie. The scene’s nestled in plain sight. But if The Phoenician Scheme has an abiding principle at its heart, it is expressed here, in a few words. Anderson’s movie is many things—a holy land caper; a robber-baron comedy; a svelte, efficient work—but, at its core, it’s a story about a man initially seeking absolution and, as he fails to get it, reaching for redemption instead. Whether that’s ultimately a successful bit of portraiture depends, like most of Anderson’s work, on the eye of the beholder.

The director’s 12th full-length release, and his fourth project since 2021, The Phoenician Scheme’s structural ambitions are relatively plain. It is not a nesting doll of stories within stories like the sun-drenched, space-age movie-about-a-play Asteroid City. It’s less interested in eroding the walls between audience and performance than his recent Roald Dahl adapted Netflix shorts. Instead, The Phoenician Scheme immediately sets about the task of sketching Zsa-Zsa’s pull on the world around him. In the film’s nifty opening credits, Anderson and cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel deploy an overhead shot that renders Zsa-Zsa, post-assassination attempt, recuperating in a bath while his domestic staff literally orbits him: cleaning his wounds, plating his food, resting a bottle of champagne in an icy bidet.

The film is Anderson’s goriest outing to date, an accomplishment for an auteur who once depicted the severing of both Jeff Goldbloom’s fingers and a Fox’s full tail, but also a conscious and effective choice to ground the industrialist world with requisite carnage. The Phoenician Scheme is no historical epic or battlefield saga—it’s a quirky, amiable, droll rumination on a certain kind of capitalist—but it doesn’t flinch from depicting the terms of moneyed ambitions. There are wounds, black eyes, arrows, bullets, grenades, and blood transfusions. As the film progresses, Zsa-Zsa begins to erode outwardly and inwardly. The man who spends most of the first 20 minutes of the film physically looming over his relations thanks to Anderson’s shot-angle mastery and sense of stage positioning goes from wondering, “Why would anybody do something I didn’t tell them to do?” at the dinner table, to offering himself as a broken-armed convert to the church.

Anderson has always maintained what Martin Scorsese once described as an abiding “tenderness” and “grace” for the characters in each of his films. Often the protagonists in his works are thorny father figures, men like Gene Hackman’s eponymous lead in The Royal Tenenbaums, Bill Murray’s respective dour dads in Rushmore and The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou, George Clooney’s adrift carnivore in The Fantastic Mr. Fox, or even Ralph Fiennes's beguiling Gustave H. in Anderson’s 2014 opus, The Grand Budapest Hotel. The director has a similar affinity for offbeat dweebs, folks in simmering existential crises, and misunderstood kids. In every case, Anderson populates his films with various types of broken individuals and sees their ideal forms, even if those forms aren't necessarily depicted in-full on screen.

This isn’t exactly a secret. Anderson has explicitly acknowledged as much. “I’m drawn to those father-figure characters,” he told New York magazine in 2004, “that are larger-than-life people.” And he’s doubled down on that, explaining in the lead-up to The Phoenician Scheme that beyond historical figures like the Armenian middleman Calouste “Mr. Five Percent” Gulbenkian, his inspiration for Zsa-Zsa was his wife’s father, a Lebanese businessman named Fouad Malouf. (The film is officially dedicated to him.)

All of this is, of course, dicey work. Anderson knows precisely what he’s doing, the coals he’s stoking, and the ways in which The Phoenician Scheme is, by virtue of its central character, in conversation with these times and with all times. The director has been projecting a surrealist reflection of the world around him since at least Grand Budapest—though it’s not a stretch to say that Mr. Fox might be an equally political work—and he’s anything but clueless as to what a man like Zsa-Zsa reminds us of as viewers in an era of strongmen and oligarchs. There are going to be folks who’ve never enjoyed Anderson’s approach, his visual and stylistic lingua franca, and they’re going to like it even less when attached not to a stop-motion fox, or a fictitious oceanographer, but to someone who brags about slave labor, and famine, and not needing “my human rights.” Folks who either don’t like or don’t care about the auteur’s graphic trickery, the fastidious frames, the ornate accoutremonts, the dry meter and biblical illusions—or who definitely don’t think a man like Zsa-Zsa is deserving of all that style. All that portraiture. And if Anderson’s movies are, as Roger Ebert once keenly termed it, so eminently “loving,” those folks won’t want to see someone the shape of Zsa-Zsa so loved.

Love, it bears saying, is not really the message embodied in the film or the man. Zsa-Zsa is never colored, or even shaded, as some sort of ideal model. The movie opens and he reconnects with his daughter out of self-interest. The film rolls and he begins to follow her God because he’s come to believe he’s liable to be damned. Later, he drops the source of his sin, but he never repents, never shows anything more than a desire to just be a normal, non-market-shaping human.

Del Toro plays Zsa-Zsa, throughout the film, as a man aware of his inhumanity and, nevertheless, unable to stop his humanity from bubbling to the surface. Anderson has confirmed as much: “Zsa-Zsa has a moral compass,” he said of the character’s earliest form, “but he doesn’t care.” The director doesn’t see him as a hero; he just sees him, in the end, as human—and that’s as much an indictment of men like Zsa-Zsa as it is a faint glimmer of hope. You may find that sappy. Or overindulgent. Or twee. Anderson has long been aware of this risk in perception, the challenge in navigating, as he likes to put it, “the edge between the corny thing and the thing that moves you.” Give it distance. Space. The Phoenician Scheme is not his best creation, but here, too, it is the sincerity of his devotion that keeps the work leaping off the screen.