Jordan Love started his seventh career game on Sunday, against the Denver Broncos. It wasn’t a bad game, and it wasn’t a good game—only 180 yards on 31 attempts is pretty rough, but he had two scores, no sacks, and no interceptions until a third-and-20 desperation heave in the final two minutes. The Packers lost, 19-17.

Here’s the thing about a quarterback’s seventh start: A seven-game sample size isn’t even half a season. Through seven games, it’s really hard to say what you know and don’t know about a quarterback. On the season, Love is completing only 57.5 percent of his passes for 6.5 yards a pop; he’s thrown 10 touchdowns and seven interceptions. Through his first seven starts, Jalen Hurts was completing 58 percent of his passes for 7.4 yards a pop; he threw 10 touchdowns and five interceptions. Last year, Hurts almost won MVP.

You can cherry-pick a seven-game stretch from the careers of most NFL quarterbacks and make them look pretty rough or pretty unbeatable. That’s why we have film to watch—to help us figure out the quality of a quarterback’s play, independent of the weekly confluence of factors that make their production difficult to trust.

But that presents a bit of a unique problem for Love because Love’s film is also the film of his rookie receivers, Dontayvion Wicks and Jayden Reed; his rookie tight end, Luke Musgrave; and his second-year offensive players, Christian Watson, Romeo Doubs, and Rasheed Walker. In fact, the entire Packers roster is young—their average Week 1 age of 25.13 was the lowest in the NFL by a substantial margin—and especially so on offense.

Sixteen Packers have taken at least 90 snaps on offense this year, from role players like Tucker Kraft and Samori Toure to every-down starters like Jon Runyan, Josh Myers, and Love. Most of those 16 are on a rookie contract. Elgton Jenkins (195 snaps), Aaron Jones (71 snaps), David Bakhtiari (55 snaps), and Yosh Nijman (23 snaps) are the only Packers on non-rookie contracts who have taken more than one snap on offense this year—and Bakhtiari hasn’t played since Week 1 and won’t for the rest of the season after suffering a knee injury.

The Packers aren’t the only team with this problem. The Falcons are chock-full of rookie contracts on that side of the ball, and they’re dealing with knuckleheaded turnovers. The Colts are there too, even after the Anthony Richardson injury, and their offensive production is a coin flip every week.

But the Falcons and the Colts have time. Richardson and Desmond Ridder have as few starts to their name as Love does, but they have years of cost-controlled football left on their contracts. Ridder will be a Falcon and Richardson a Colt and Bryce Young a Panther and C.J. Stroud a Texan for the next few seasons. Their teams have time to let each player grow, develop, and prove they deserve the starting job and the second contract that every quarterback pursues.

The Packers don’t have that time with Love. Which makes the youth of the roster—and the challenges it presents in evaluating Love—all the more dire.

A young team, no matter how well coached, will inevitably be a mistake-riddled team. That’s the nature of young players. They have mental lapses, miss details, and lack muscle memory. They panic more easily and let mistakes compound; they can’t compensate for one another, either. Matt LaFleur said as much after the loss to the Broncos this week: “[Love’s] done enough for me to show me it’s all right there. And it’s not just him. It’s getting the other 10 on the same page. It all works in unison. So the better everyone is around him, the better he’s gonna look.”

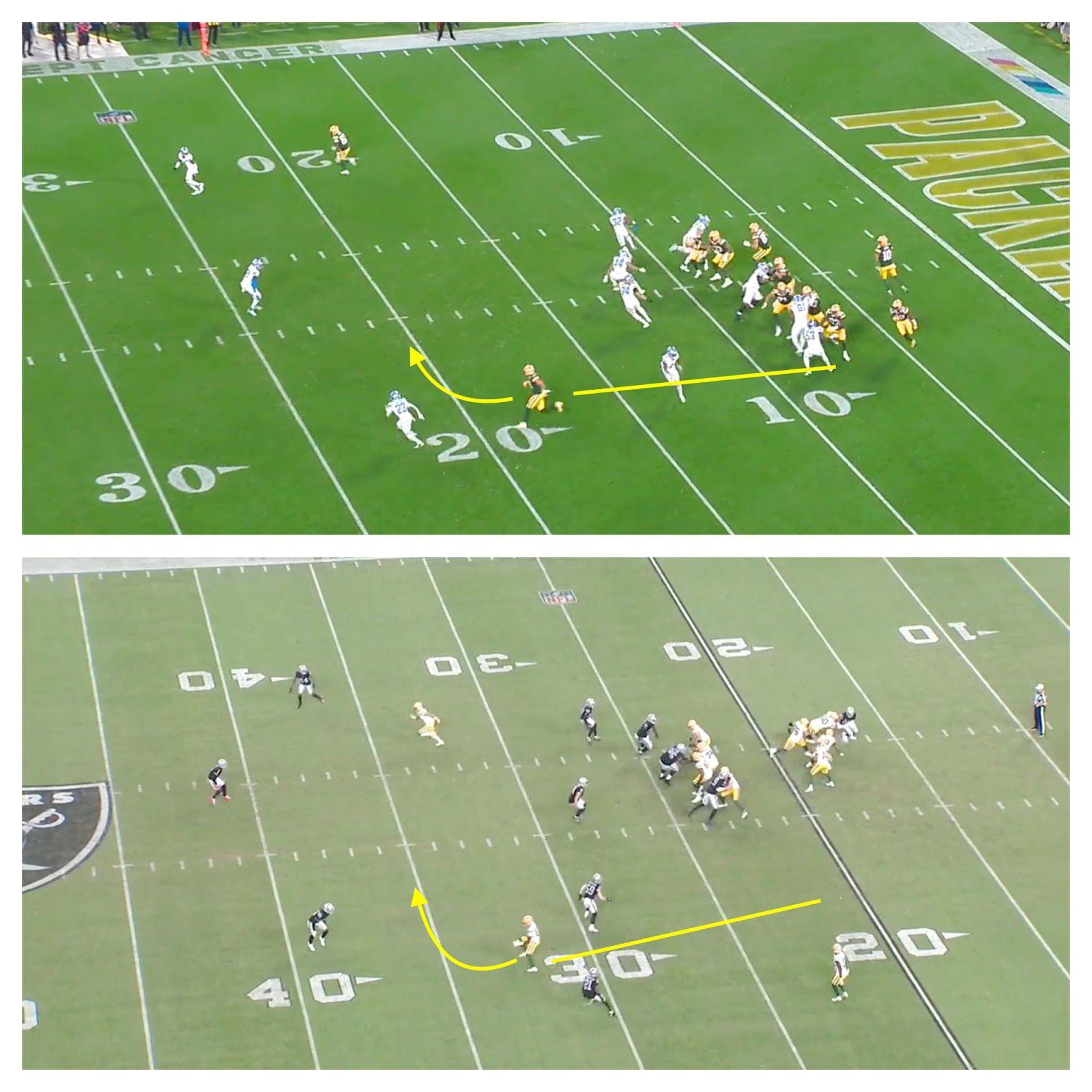

Let’s pick an example. Here’s an interception that Love threw against the Raiders, directly into Robert Spillane’s hands.

And here’s a similar interception against the Lions, right to linebacker Alex Anzalone (who tips it for the Jerry Jacobs pick).

Only they’re not really that similar. On the first play, Love is at fault. He assumes the play-action fake will easily and effortlessly pull the linebacker out of the throwing window for the drift route, but Spillane has seen this route and this fake plenty of times on the Packers film, and he sinks right under the route. This is blind trust in the offense, and while sometimes it leads to sick “anticipation” throws, it’s largely a bad idea for this exact reason.

On the second play against the Lions, it’s not Love who is wrong at first—it’s the receiver. Christian Watson doesn’t run the route correctly. He’s supposed to be much wider on the route, getting close to the bottom of the numbers before breaking back to the middle of the field.

Because Watson doesn’t gain the appropriate width, Love has to throw this ball into coverage. Of course, Love could still choose to eat this throw and cut his losses; but that’s how the mistakes of young players compound. Here’s another mistake, against the Bears: Love thinks the receiver should settle, Malik Heath thinks he should break inside, the interior of the line blows a block, and the pass is uncatchable. On this simple route, which is supposed to be a staple of LaFleur’s offense, Love and his receivers cannot get on the same page.

You can look at the potential game-winning, but ultimately game-losing, drive against the Raiders as another example of how mistakes snowball. The Packers had drops, Love was late to throws, and Watson got big-boyed by a 5-foot-9 corner.

Or the final drive against the Broncos, which saw the Packers in field goal range at the two-minute warning. A needless hold on second-and-10, a missed read and late throw from Love on second-and-20, and you end on another interception to seal the game.

It would take forever to go into every game and cycle through execution error after execution error—detail all the false-start penalties (10 total, tied for fifth in the NFL) and how they affected each drive. The Packers are sloppy right now, and it isn’t so much a product of coaching as it is a product of youth, and youth isn’t going away.

So let’s focus on the issue at hand: Love. Jordan Love is in his fourth year in the NFL—that’s the length of the standard rookie contract. As a first-round pick, Love did have a fifth-year team option attached to his deal, but the Packers and Love agreed to a restructure. Now, Love’s contract looks like this.

Next year, Love will cost the Packers $7.5 million on the cap, and it would cost them more to move on from him ($12.5 million) than to keep him on the roster. After that? His deal is up. Love will be on the Packers roster for the rest of this season and through next year, but after that, the Packers’ future at quarterback isn’t locked in.

Accordingly, the Packers can’t start thinking about the future of their quarterback situation next offseason; that’ll be too late. Teams don’t wait until a quarterback’s deal is done to sign them to an extension (unless they’re the Giants). You have to lock them in early. So the Packers have to start thinking about their commitment to Love this offseason. Which means Love doesn’t definitely have 1.5 years to prove he’s the guy: He might have just the next two months.

That’s a tough draw for anyone—it’s an especially tough draw for a quarterback working with the league’s youngest offensive roster, where the mistakes of other players can end drives, ruin scoring opportunities, take Love off the field, limit his reps.

But what else is Love supposed to do? And what else are the Packers supposed to do? Get a veteran receiver at the trade deadline to stabilize the passing game? Who would be available, really warrant a lion’s share of the targets, and not cost an arm and a leg? And would that player even be able to get up to speed and make an impact before the season is essentially over?

This is the reality the Packers committed themselves to suffering a few years ago, when they were building a contender in the waning years of Aaron Rodgers’s career; when there was no money to pay Marquez Valdes-Scantling and Allen Lazard; after Davante Adams was traded away; once the vaunted 2010s offensive line got old. The Packers have been drafting all over the offense in recent years (five of their top seven picks in the most recent draft, four of the top six in the previous one, and three of the top four in the year before) to account for the changing of the guard. But without hitting at ludicrous rates, and with the untimely injuries to Jones and Bakhtiari, they’re stuck with this version of the offense.

The only way out is through. There’s nothing for the Packers to do now but slough through the long, bumpy trails of development and hope that every week looks a little bit better, a little sharper, a little improved. Then, at the end of the season, you can pick your head up and evaluate where you are as best you can. It won’t be easy, but you have to make a decision. If you don’t need a quarterback, great. If you do need a quarterback, well, welcome to the world that every other NFL franchise has been living in for the past three decades. Drafting and developing sure is nice, but eventually, you miss.

The Packers don’t know that about Love—yet. He’s got two months to get better, and I think he can. But there’s a lot to prove, and that’s all the Green Bay offense is now: one big, messy proving ground.