The Key to Adapting Video Games Is to Make Them Into Television

The early subpar reviews of ‘Uncharted’ are a reminder that video games aren’t stories so much as they’re environments. You settle into them. Which is why a quiet redemption for video games is unfolding not in cinema, but in streaming television.

For nearly 30 years—since the ill-fated theatrical premiere of Super Mario Bros. in May 1993—gamers have met movie adaptations of video games with a certain trepidation.

Take Uncharted, releasing on Friday, starring Tom Holland and Mark Wahlberg, and adapting the video game series about a wisecracking treasure hunter named Nathan Drake. From a critical standpoint, it’s dead on arrival. It’s the same old story of a big-budget, top-tier cast employed in service of goofy set pieces straining under the weight of comparisons to the original animated cutscenes and gameplay (and also, in the case of Uncharted, to Indiana Jones). But adaptations like this aren’t for total lack of enjoyment or success over the years. Director Paul W.S. Anderson’s Resident Evil series, starring Milla Jovovich and spanning six movies over 14 years, was a $1.2 billion worldwide box office miracle. Detective Pikachu wasn’t half-bad! The new Mortal Kombat was actually a delight.

But the exceptions prove the rule. The dissatisfaction runs deeper. These outliers are either flukes (Detective Pikachu, Sonic the Hedgehog) or perverse triumphs of bad taste (Resident Evil, Mortal Kombat). In either case, they’re well short of proving the long-term mainstream viability of video game movies akin to comic book movies via Marvel and DC. That’s the real dream here. That’s the in-game achievement eluding these films, even the reasonably successful ones. They’ve yet to standardize the art of the video game adaptation to the big screen.

This is despite video games, such as Uncharted and The Last of Us from the developer Naughty Dog, having spent the past couple of decades learning the art of the Hollywood blockbuster. Activision casts Kevin Spacey and Tom Hanks in Call of Duty; Kojima Productions casts Norman Reedus and Mads Mikkelsen in Death Stranding; CD Projekt Red casts Keanu Reeves in Cyberpunk 2077; Guerrilla Games casts Carrie-Anne Moss and Angela Bassett in Horizon Forbidden West. I could go on. Clearly video game developers wish to meet Hollywood halfway, so the continued failure of these movie adaptations perhaps suggests a deeper hostility in Hollywood or perhaps a fundamental incompatibility. That’s the thinking behind the notion of a “video game curse” in Hollywood. Maybe there’s just no adapting the interactive premise into a passive format to any enduring satisfaction. A gamer walks into a cinema. He’s got no controller, no mouse, no keyboard, no pad, no sticks. He can’t win.

This insecurity about movies haunts video games in so many ways. Ten years ago, the late Roger Ebert dissed The Last of Us upon the game’s reveal at E3. On Twitter, Ebert cosigned the columnist Steven Boone’s complaint about “loud, assaultive, photorealistic game design that rewards wispy attention spans while demanding minimal problem-solving skills of its players.” The Last of Us wanted to be a summer blockbuster so bad. Developers and gamers aspire to cinematic excellence while movie directors still routinely fail to “get” video games. This was the persistent existential challenge for big-budget video game development in the 2010s. How could video games finally earn the sort of respect that movies first earned nearly a century ago? It’s a discourse out of fashion now, but video game critics spent a decade agonizing about the industry’s struggle to produce its own Citizen Kane. Meanwhile, Hollywood struggles to produce a video game adaptation on par with The Dark Knight in its potential to outgrow the source medium and at last earn some real money, power, and respect. Still, the odd, modest success in adapting some video games suggests a more complex problem—but a solvable one.

There’s already a quiet redemption for video games in streaming television. It began a few years ago with Netflix adapting Castlevania, a classic video game series now a couple of decades out of fashion, into an animated series for “mature audiences.” In four seasons, Castlevania matured, sure enough, into a great show with impressive ratings. Its success wasn’t so complicated and its strengths weren’t so impossible. It was a popular title developed into a rich character drama driven by lovely writing and stylish confrontations. This is the way. In November, Netflix premiered its League of Legends adaptation, Arcane, an animated action-adventure series with a moody ensemble of magic wielders waging a bio-punk class war. Fortiche, the French animation studio behind Arcane, blends 3D computer graphics with gorgeous hand-painted textures. The series’ protagonist, Vi, and her disillusioned sister, Jinx, splatter color and passion everywhere.

Mind you, League of Legends isn’t a story-driven video game. It’s a top-down online multiplayer battle for map control. A listener writing in response to a recent discussion of Arcane on Sound Only told me he’d played League of Legends for years and never once bothered with learning the character backstories until watching Arcane. I’d never even played League, but I marveled at every minute of Arcane and considered the implications for the so-called video game curse. Video games aren’t stories so much as they’re environments. You settle into them. You kick around. You learn to live with the premise. It’s why movies, one of the briefest mass media formats compared to books, television series, or even podcasts, have always made for a strange benchmark for the dramatic potential of video games. The player’s engagement in a video game, even in the most self-consciously “cinematic” titles, has always more so resembled serial literature and seasonal television.

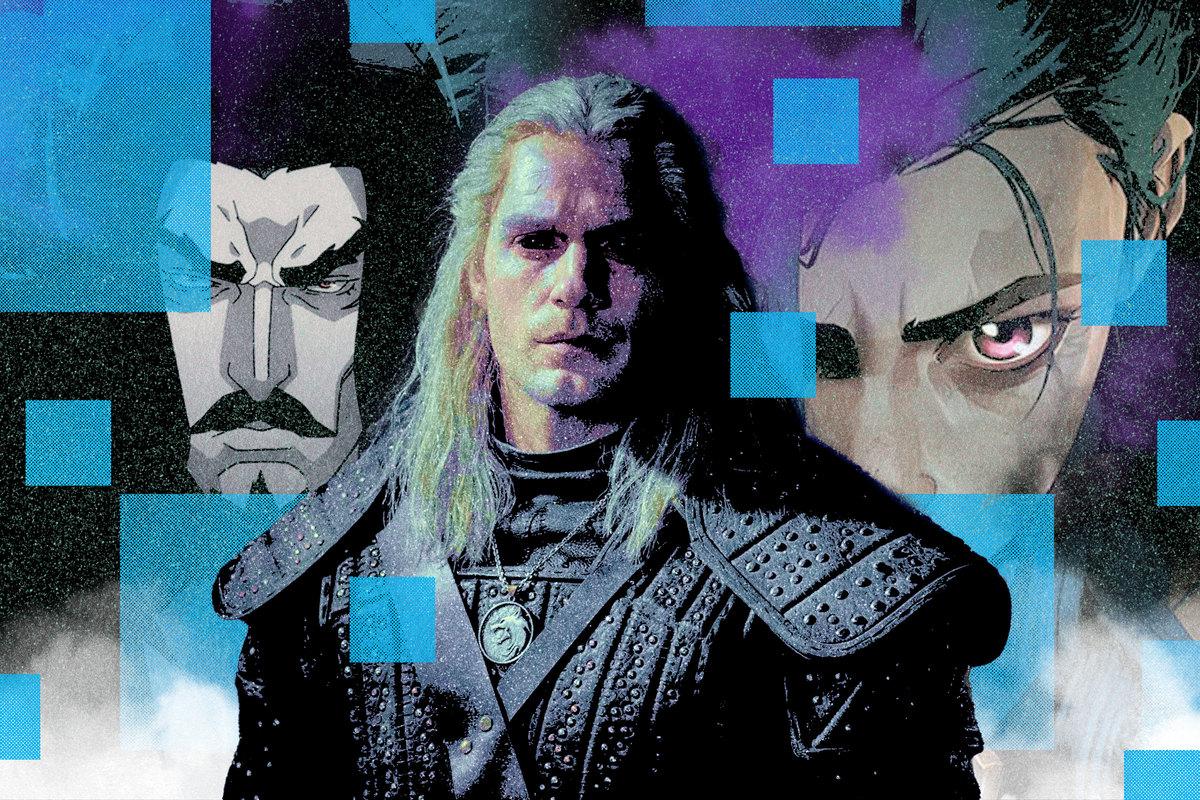

It shouldn’t surprise anyone to see that television is the superior medium for video game adaptations after all. Castlevania and Arcane are animated series, 2D and 3D respectively, but that’s still not accounting for the core challenge for video game adaptations: live-action. That’s the fertile frontier. In 2019, Netflix adapted The Witcher from Andrzej Sapkowski’s six-part series of high-fantasy novels, popularized in the U.S. by the role-playing video game adaptations—chiefly, The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt—developed by CD Projekt Red. It’s not a video game adaptation, strictly speaking, but it’s close enough to the cause. It’s a good sign. The Witcher, starring game series superfan Henry Cavill as the legendary monster slayer Geralt of Rivia, ranks with Stranger Things and Bridgerton among the most popular shows on Netflix.

Now in its second season, The Witcher leads a larger bet on streaming television as the ideal medium for live-action video game adaptations. HBO is adapting The Last of Us into a live-action series starring Pedro Pascal and Bella Ramsey, Amazon is adapting Fallout, and Amblin is adapting Halo for Paramount+. This isn’t to suggest a movement away from live-action movie adaptations. Just a couple of days ago, Netflix announced an upcoming adaptation of BioShock. Oscar Isaac will play Solid Snake in the forthcoming Metal Gear Solid for Sony Pictures, and we’ll see how that plays out on the big screen in a couple years. For now, though, the television adaptations mark a new cause for, dare I say, optimism about video games in Hollywood.

The streaming wars have produced a glut of content, particularly television. On first thought, it’s frustrating to see titles like Arcane excel on so many levels short of critical praise beyond the video games press. But I wonder whether the overabundance that’s distracted critics from Arcane is the very reason for its creative and commercial success. It flourished in a low-stakes, no-rush environment with its first season dedicated to just laying the groundwork. The rest is uncharted territory.