Baseball is back, and with it the opportunity for preseason predictions. Do the Dodgers once again start the year as World Series favorites? Will any team break out like the Giants did last season? And how will things shake out in the juggernaut AL East?

Below are our MLB team’s picks for the 2022 season. Some of them seem obvious, but others may surprise you. Read on to get a sense of who we think will be great (and who could flop) this year. And be sure to check out the rest of our preview coverage here.

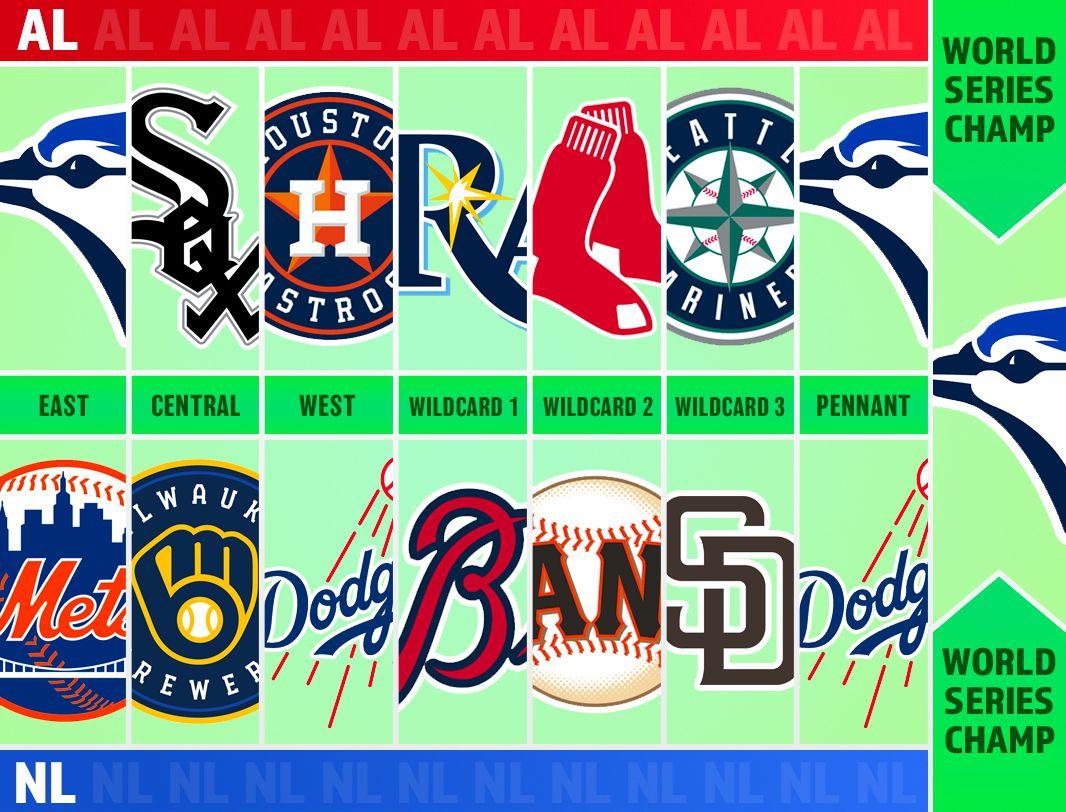

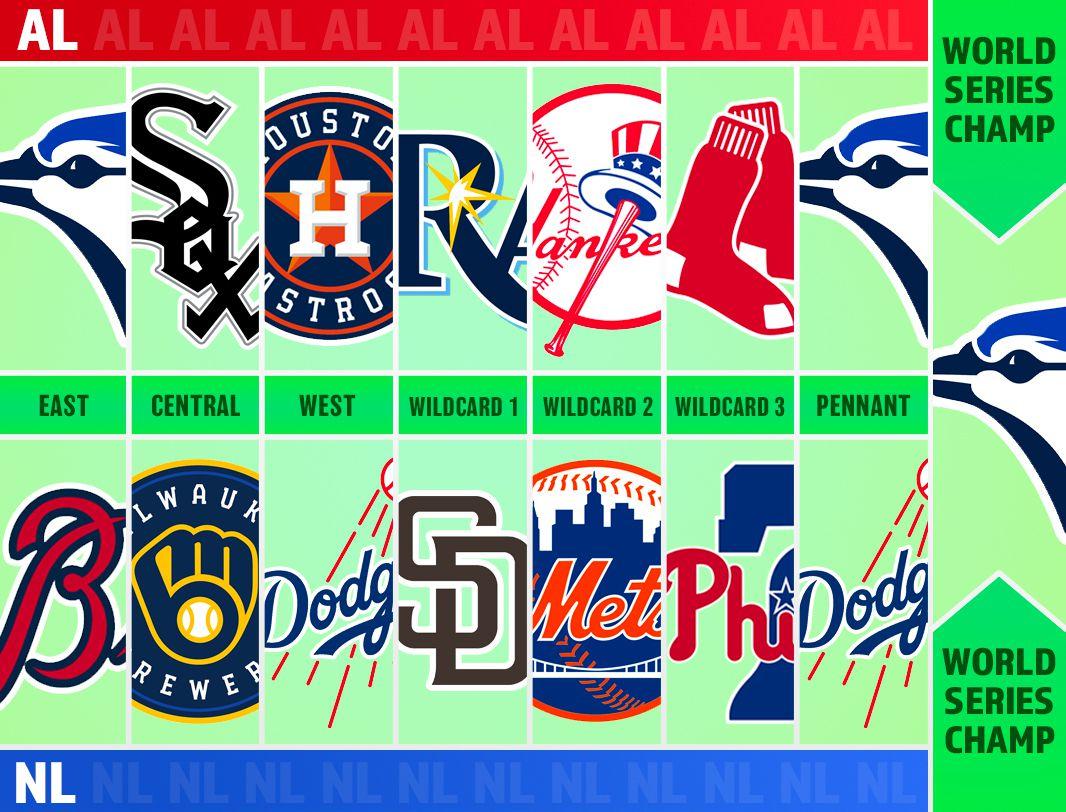

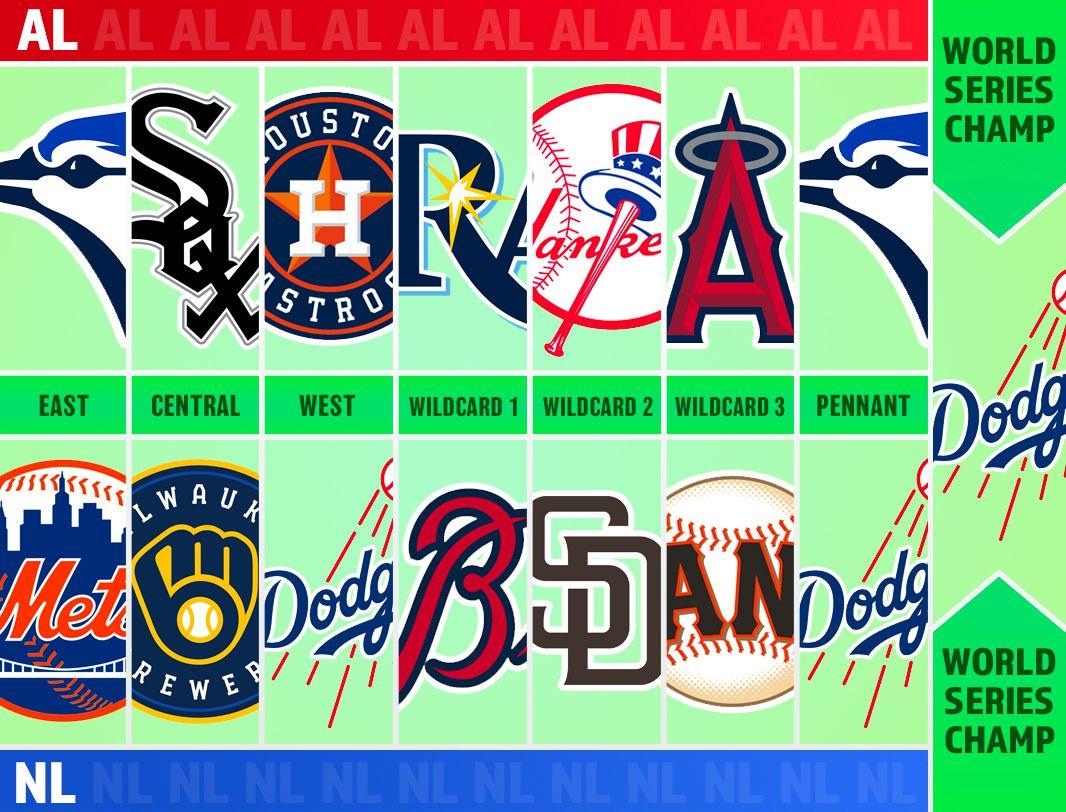

Michael Baumann: If you’ve followed The Ringer’s baseball coverage for any length of time, you know I’m an absolute flop-sweating freak for the 2015 Blue Jays—and a return to those magical Ontario days is so close I can taste it. Imagine the first international World Series in 29 years: the Hyun Jin Ryu revenge tour; the Dodgers’ second chance at 2017 World Series MVP George Springer; Guerrero and Bichette vs. Betts and Buehler. After years of economic and societal anxiety darkening the game, we deserve this.

Ben Lindbergh: Look, at a certain point a person gets tired of picking the Dodgers to win the World Series every year. They’re still probably the best team in baseball, and they’ve won pennants in three of the past five seasons, but their age and depth are big enough sources of uncertainty (relative to earlier Dodgers juggernauts) that there’s an opening for the new hotness. Last year, I picked Toronto as my flop team, concluding, “there’s a real risk that the Jays’ season will end after 162 games, which would be a disappointment after an active offseason created high hopes.” I was right in the sense that they did miss the playoffs, but wrong in the sense that they didn’t deserve to.

Now they have a whole season with one home park, a possible advantage derived from some opponents failing to comply with Canada’s vaccine mandate, and Matt Chapman, Kevin Gausman, Yusei Kikuchi, and full seasons from José Berríos, Alek Manoah, and a healthier Springer to offset the departures of Marcus Semien, Robbie Ray, and Steven Matz. These guys are gonna be good, so I’m downgrading the Dodgers from championship team to mere runners-up. Apologies to fans of AL and NL Central teams for possible bicoastal bias; someday the Centrals will wake up and realize that one-sixth of the predicted playoff teams is not enough for one-third of the divisions, but I doubt divisional equality will come in 2022.

Zach Kram: Toronto plays in the toughest division in baseball and just lost the reigning AL Cy Young winner and third-place MVP finisher. Yet I don’t care, because Toronto will compensate for those losses and more with the additions discussed above. Plus the Blue Jays are sure to avoid last season’s rotten luck, which saw them fall eight wins short of their “expected” record based on run differential. The Blue Jays will thrill, entertain, and ride their talented lineup and rotation to a victory in a rematch of the 1992 World Series, denying Atlanta—which will return Ronald Acuña Jr. from injury and benefit from a bolstered rotation and relief corps—a repeat title.

Bobby Wagner: Far be it from me to question the guarantees of Dave Roberts, who told the press that the Dodgers will, definitively, win the 2022 World Series (before walking it back and saying they’d win if the rotation stays healthy; stick to your guns, Dave!). The Dodgers are pretty clearly the best team in baseball. That doesn’t always insulate a team from disaster, and I don’t feel particularly confident in any team this early in the calendar, but this group is virtually flop-proof. Now we’ll have to wait and see what bizarre and soul-crushing way they’ll fall just short in October.

AL MVP

Lindbergh: Shohei Ohtani, Angels. I’ve picked Ohtani’s teammate Mike Trout to be AL MVP in each of the five past seasons, and in 2018, I declared that I’d do so every year until Trout was traded to an NL team or 2024, whichever came first. Trout hasn’t been traded, and it’s not yet 2024, but I think I can escape my commitment under an act of God clause triggered by Ohtani’s divine production.

Ohtani was my Rookie of the Year pick in 2018, and he won the award. He was my breakout player pick last year, and damn, did he ever break out. He says he can improve his numbers “across the board” this season, and he might be right, thanks to the prospect of longer outings on the mound and the plate-appearance boosts that could come from the universal DH, the “Ohtani rule,” and batting at the top of the order (protected by Trout). Because his dual roles afford him the opportunity for more playing time than anyone else can accumulate, it’s hard to imagine a healthy Ohtani not winning this thing again. And while it’s not nearly as hard to imagine him getting hurt, I certainly don’t want to.

Kram: Vladimir Guerrero Jr., Blue Jays. I don’t trust that Trout will stay healthy or that Ohtani will replicate the most magical individual season of my lifetime. I do, however, trust that Guerrero will mash once again, and that the Blue Jays’ team performance will give him a narrative boost.

Wagner: Mike Trout, Angels. This is the first year in my professional career that I so much as wrote someone else’s name in a short list of AL MVP candidates, before winnowing it down to Trout as the chalk pick. Ohtani did more than earn it last season, as did the runner-up, Guerrero Jr. And I think it’s more or less an even toss-up between those three. But as a sign of respect, I’ll pencil Trout in from muscle memory one last time.

Baumann: Trout. I’ll say this: For the first time since 2013, I considered picking another AL MVP favorite. But only briefly.

NL MVP

Wagner: Francisco Lindor, Mets. It’ll take a damn-near-perfect season from Lindor to win MVP in a field this crowded. Just in Lindor’s division, there’s Juan Soto, arguably the best player in baseball; Bryce Harper, the reigning MVP; and Ronald Acuña Jr., a bona fide five-tool perennial MVP candidate. So why Lindor? After seeming uncomfortable in the first month and a half of his first season with the Mets, he turned things around and finished exceptionally strong—even while the Mets were nosediving. He’s an elite defender at shortstop, and it’s easy to forget that Lindor, now entering his eighth season, is only 28, at the apex of his athleticism and in a lineup that is drastically improved around him. Finally: We know this is at least partially a narrative award, and it’s a good story for the $341 million man to be humbled by the bright lights of New York and bounce back in his second season to win MVP. Even if you don’t think that’s a good story, the overrepresented New York media probably will.

Kram: Mookie Betts, Dodgers. I wrote last year that until he gives a reason for me to doubt him, I’ll just keep picking Betts to become the first player since Frank Robinson to win MVP in both leagues. And one down year isn’t enough to sway me. After all, even in a relatively lackluster 2021 campaign, Betts was still worth 4.2 WAR in just 122 games—the pace for a near-MVP-level 5.6 wins across 162 games. Advanced stats always love him, and if he’s healthy, he’ll rack up a ton of counting stats in this Dodgers lineup, too.

Lindbergh: Juan Soto, Nationals. Soto is more likely to lead the league in WAR—which he nearly did last year—than to win the MVP award, because his teammates aren’t going to get him to the playoffs or help him rack up counting stats (aside from walks). Then again, being the best player correlates more closely to winning awards than it once did, and Soto’s second-half hitting (199 wRC+) may have been MLB’s best two-ish months since … well, Soto’s 2020 (201 wRC+). The 23-year-old is an offensive savant, and if OBP is life, Soto is its cradle and building blocks.

Baumann: Soto. At some point it’ll become conspicuous that Soto hasn’t won an MVP yet, like how LeBron James didn’t win one until his sixth year in the NBA. How did that happen? Soto came close last year, picking up six first-place votes in a second-place finish to Harper. But eventually, we’ll understand that this kid with a .432 career OBP—again, for those of you in the back, FOUR (pounds table) THIRTY (pounds table) TWO career OBP—is by far the best hitter in the game right now. Maybe the best since full-BALCO Barry Bonds.

AL Cy Young

Kram: Gerrit Cole, Yankees. Out of Cole’s four seasons since leaving the Pirates, 2021 represented his worst by ERA, WHIP, innings pitched, and strikeouts (the last two excepting the shortened pandemic season). Yet he still finished second in the Cy Young vote. He’s the safest choice here—especially as he’ll pitch in front of a much-improved Yankees defense in 2022.

Lindbergh: Cole. Is it just me, or are most of the sport’s impressive starting pitchers now in the National League? Not only is Cole the leading contender for this award, but I don’t see a logical case for picking anyone else. Shane Bieber, who missed most of last season? Robbie Ray, who won it last year but entered 2021 with only one season (2017) of 2 or more Baseball-Reference WAR? Lucas Giolito, who’s never thrown 180 innings or recorded a full-season ERA as low as 3.40? Ohtani, who’ll be limited by a six-starter rotation? A post-TJ, 39-year-old Justin Verlander? I’m not saying Cole will win—you have to take the field over any individual—but the AL is light on no-doubt aces, and after four consecutive top-five finishes (two of which were top-two finishes, including last year’s), Cole is the clear favorite.

Wagner: Cole. Every year when I sit down to pick an American League Cy Young winner, I think that Cole’s already won one. He deserved it in 2019 and lost to his own teammate, Justin Verlander. And he was close in a wide-open field last year, yet struggled too much in the middle of the year to lock it down. With an improved defense behind him, I think this is the year.

Baumann: Shane McClanahan, Rays. Thought about Cole or Bieber, but I didn’t want to be boring. Maybe I’m just overawed by the velocity—and for good reason, since McClanahan is the hardest-throwing left-handed starter in the majors. Yes, when hitters caught up to his fastball last year, they hit him pretty hard, but as a rookie getting his first taste of MLB action, McClanahan made 25 starts, posted a 115 ERA+, and struck out 27.3 percent of opposing hitters. And he’s on a team where he’ll have a lot of help. The Rays have a good defense, and are good at developing young pitchers. When Blake Snell and Tyler Glasnow were 25—the age McClanahan is now—they both posted ERAs under 2.00. Snell won the Cy Young.

NL Cy Young

Kram: Sandy Alcantara, Marlins. I have to balance my Cole pick in one league with a dark horse in the other. Alcantara might not have the strikeout numbers—just 8.8 Ks per nine innings last season—of most Cy Young hopefuls. But he was quietly excellent in 2021 (205 2/3 innings, 3.19 ERA) and has one advantage in his favor: He suffered from the worst catcher framing in the league last season, according to Baseball Savant, and this offseason, the Marlins traded for Gold Glove catcher Jacob Stallings. That subtle boost should give Alcantara the edge to take yet another step forward in 2022.

Wagner: Zack Wheeler, Phillies. At the risk of reigniting the quality vs. quantity innings debate of 2021, Wheeler’s body of work deserves a Cy Young. He’s flying in the face of the most dominant pitching trend in baseball right now: smaller workloads for starters. And while it’s good for the game that there’s now room to reward the godly rate stats of Corbin Burnes, there’s also still room to reward a dominant pitcher throwing seven-plus innings every time he takes the ball.

Baumann: Carlos Rodón, Giants. So many of the NL’s elite pitchers are starting the season compromised by injury: Jacob deGrom, Zack Wheeler, Luis Castillo, the list goes on. So this stands to be a wide-open race. I love Rodón’s fit in San Francisco: good ballpark, coaching staff well-established as rescuers of former top prospects. And Rodón is less of a project than, say, Kevin Gausman was this time two years ago—frankly, he could’ve won the Cy Young last year if he’d made about six more starts. He’ll make good on his potential this time.

Lindbergh: Corbin Burnes, Brewers. It usually takes a little luck to have a Cy Young season, but not in Burnes’s case. Burnes somehow won the Cy last season despite underperforming his peripherals and Statcast-based expected stats; his 2.43 ERA was almost 0.8 runs higher than his 1.63 FIP, one of the biggest gaps in the game. I mean:

Throw in the potential to make more starts this season, and back-to-back Burnes wins wouldn’t be a big surprise.

AL Rookie of the Year

Baumann: Spencer Torkelson, Tigers. The AL rookie record for home runs in a season is 52, set by Aaron Judge in 2017. Just keep that in mind.

Lindbergh: Bobby Witt Jr., Royals. Adley Rutschman may be the best of the AL rookies, but he also may not make the majors for a month or more, which will give probable Opening Day debutants Witt, Julio Rodríguez, Torkelson, and Steven Kwan time to rack up counting stats before he arrives. Witt has the highest average prospect ranking, most Triple-A time, and (as a shortstop) lowest offensive bar of the bunch, so he has the edge.

Wagner: Witt Jr. This used to be my least favorite award to choose, because you have to factor in service time manipulation and how that will affect the production of each player. But we’ve already gotten confirmation that Torkelson, Rodríguez, Shane Baz, and Witt Jr. will break camp with the major league teams.

So why Witt Jr. over those other candidates? He plays for a team just good enough for people to watch, but just bad enough that he won’t lose at-bats if he slumps. Plus, everyone loves mammoth home runs from 21-year-old shortstops with cool names.

Kram: Julio Rodríguez, Mariners. I was tempted to take Twins starter Joe Ryan as a sleeper pick, but it’s hard to pick against a member of the Witt-Torkelson-Rodríguez top prospect trio. Give me the best pure hitter of the bunch, as Rodríguez slashed .347/.441/.560 across High-A and Double-A last season, then so impressively crushed spring training pitching (.424/.487/.818) that he forced his way onto the Mariners’ Opening Day roster.

NL Rookie of the Year

Baumann: Max Meyer, Marlins. Meyer is a bit undersized at an even 6 feet, but he throws in the upper 90s with a killer slider and is working on a changeup. Plus, he’s a good athlete; he played hockey as well as baseball growing up outside of Minneapolis, and in addition to pitching at the University of Minnesota, he played in the outfield and hit .256 as a sophomore.

Can anyone think of any other 6-foot pitchers who were high-level hockey players and could also handle the bat? How about Tom Glavine? Now imagine Glavine as a right-hander with an additional 7 miles an hour of fastball velocity.

Lindbergh: Seiya Suzuki, Cubs. Keibert Ruiz isn’t rookie eligible—sorry, sportsbooks—but even if he were, Suzuki wouldn’t be a bad bet to become the fifth NPB player to win an MLB Rookie of the Year award. The 27-year-old has arguably been the best player in Japan for the past few years; according to DeltaGraphs, his WAR totals easily led all NPB position players in 2019 (8.1) and 2021 (8.6). Projection systems’ expectations range from “above average” to “star,” and scouts are similarly sanguine about his ability to hold his own (at minimum) in the majors. Suzuki’s offensive output in Japan compares favorably to that of almost every previous player who’s made the NPB-to-MLB transition, and he brings a good glove, too. Between all of that and his clear path to playing time, he has the inside track.

Wagner: Suzuki. In most circles, Suzuki is the overwhelming favorite for this award. And why not? He has a long track record of exceptional production in Japan. His bat is the most surefire tool of anyone in the NL rookie field, and he’ll almost certainly get 500 ABs this year, barring injury. That’s more than you can say for fellow contender Oneil Cruz, whom the Pirates inexplicably sent down to minor league camp. It’s not a guarantee that Suzuki will hit 10 to 15 percent better than league average, but it’s pretty likely. That will be hard to beat for anyone in the field, especially if they don’t play a full season.

Kram: Suzuki. The sport’s top six prospects, according to both FanGraphs and Baseball Prospectus, will all play for American League teams; so in a shallow field, I’ll pick Suzuki, who is an MLB rookie but accomplished NPB veteran. The new Cub was better than a .300/.400/.500 hitter in each of his last four seasons in Japan. FanGraphs’ projections peg Suzuki with a .877 OPS this season, right behind Betts and Max Muncy and right ahead of Corey Seager and Alex Bregman. I don’t believe that he’ll instantly be a top-20 hitter in the majors—but given his likely playing time, Suzuki could fall well short of that target and still be Rookie of the Year material.

Breakout Player

Wagner: Tanner Houck, Red Sox. On the surface, Houck put together a very solid season in 2021: a respectable 2.2 WAR, with a 3.52 ERA in 69 innings. And if you dig in a little deeper, you’ll find a 2.58 FIP, a mix of speed and movement on his pitches that Baseball Savant says is reminiscent of 2021 breakout darling Logan Webb, and the fact that Houck scored in the 80th percentile in almost every important Statcast category for a pitcher, including K%, Whiff%, expected ERA, and expected batting average.

Is all of this a mirage? Maybe. But when I watch Houck, I see a pitcher with unique arm action who’s added almost 2 miles per hour to his fastball since his debut, and whose slider looks impossible for hitters to pick up out of his hand. Translation: a 25-year-old pitching prospect who strikes a ton of guys out and has trimmed his walks significantly. Houck won’t be knocking on the door for the Cy Young any time soon, but he’s shaping up to be a pretty good no. 2 or 3 starter, should the Red Sox ever get Chris Sale back.

Kram: Nick Madrigal, Cubs. Among all active players with at least 300 plate appearances, Madrigal has the lowest career strikeout rate, at 7.4 percent—and that figure still represents a 2.5-fold increase over his 3.0 percent minor league rate. Now on the north side of Chicago after last summer’s Cubs–White Sox swap of Craig Kimbrel, Madrigal will play his first full season after missing large swaths of 2020 (to the pandemic) and 2021 (to injury). And won’t it be fun to watch a young player hit .330 or so, and pair that contact-oriented approach with solid defense and baserunning?

Lindbergh: Triston McKenzie, Guardians. Between Bieber in 2019, Burnes in 2020, and Ohtani in 2021, I’m riding a hot streak here. I have a high bar for what constitutes a breakout—no very recent top-tier prospects (Jarred Kelenic) or players coming off strong seasons (Dylan Carlson)—so I’m going to return to my 2019 strategy and go with a Guardians pitcher. I’m not sure McKenzie will wind up with the hardware that the Bieber-Burnes-Ohtani trio has earned over the past few years, but there’s a lot to like about his up-and-down 2021.

Dr. Sticks was a walk-prone mess at the start of last season, but in an 11-start stretch that followed his reinstatement from Triple-A, he posted a sub-3.00 ERA with 68 strikeouts and 11 walks in 67 frames. If we slice his season still further, we find a seven-start, 1.76 ERA stretch from August 5 through September 14, a span of several weeks during which McKenzie was the most valuable pitcher in the American League. McKenzie came back from the minors with a speedier fastball and a more unflappable mindset, and he should last longer, too; the righty lost all of 2019 to muscle strains and much of 2020 to the pandemic, but his 141 1/3 pro innings pitched last season set him up for a durable and dominant 2022.

Baumann: Alejandro Kirk, Blue Jays. The Blue Jays backstop has become a bit of a fan-favorite figure because at 5-foot-8 and 265 pounds, he’s shaped like a friend. But before this becomes a repeat of the semi-patronizing latter-day Bartolo Colon discourse, let’s throw a couple other facts out there. In 189 plate appearances in 2021, Kirk had a higher walk rate than Paul Goldschmidt, a lower strikeout rate than Jose Altuve, and a better ISO than Bo Bichette. Kirk isn’t some novelty act: He’s going to grow up to be a Yuli Gurriel, or maybe a Dmitri Young.

Flop Team

Baumann: Yankees. Right now, I think the AL Wild Card race is about six teams deep: the Rays, Red Sox, Yankees, Twins, Angels, and Mariners. Maybe seven if the Tigers find their magic sooner than expected. Of those teams, the three AL East clubs look a cut above the rest on paper, but in reality, the Red Sox and Yankees are still a little … meh. Maybe the East will get four teams into the playoffs, but one will probably take a few injuries, lose a couple bad intradivision games, and fall out of touch with the pack. Might as well be the Yankees.

Kram: Padres. What a difference a year makes. This time last spring, I thought the Padres would win the World Series. Oops. Now I see a team with its best player, Fernando Tatis Jr., out for half the season, and a shockingly shallow lineup, featuring Eric Hosmer and Wil Myers every day and now also relying on the likes of Nomar Mazara and Ha-seong Kim. With the Dodgers still dominant and the Giants still looking like contenders—even if not the 107-win juggernaut they were last season—the Padres will have to keep waiting to break through in the NL West.

Lindbergh: Phillies. I waffled for a while between the Giants and the Cardinals for my final NL wild-card pick before landing at last on the Phillies. I’m pretty sure I made a mistake. By adding Castellanos and Kyle Schwarber to what was already MLB’s worst defensive team, the Phillies have reached a level of defense so putrid that it’s tough to win no matter what you do well. Dave Dombrowski may have misunderstood the assignment: “Universal DH” doesn’t mean you have to have a DH at every position.

I like the rotation, I like the lineup, and I like the idea of watching the latter try to hit its way out of its defensive self-sabotage, but putting post-rebuild distance between the Phillies and .500 shouldn’t be this hard. As I wrote when I made them my flop pick in 2020, “it’s disappointing that one has to squint to see the payoff that was supposed to have happened by now. In the sense that their farm is fairly barren and they’re still struggling to assemble a playoff favorite, the Phillies have already flopped.” I wouldn’t be shocked if I end up pasting those sentences into next year’s predictions post too.

Wagner: Twins. Because half the league isn’t trying to win, it’s hard to completely flop if you put a modicum of effort (and resources) into your team. That being said, I think the Twins find themselves in an awkward position. After an extremely disappointing 2021, they seemed ready to take a step back. Then Scott Boras sent one text and Carlos Correa, the best free agent on the market, fell into their laps. Now they find themselves looking to bolster a major league roster that is very thin on pitching, given that their ace is actually in a Toronto Blue Jays uniform. Signing a player as good as Correa is always the right move. I’m just not convinced it’s enough.

Surprise Team

Lindbergh: Angels. Last year I had a hard time picking a surprise team, even though the Giants—the surprise team to end all surprise teams—were right there. (Which just goes to show that a true surprise team isn’t foreseeable.) This year I can talk myself into the talents of many non-playoff-favorites, including the Marlins, the Mariners, the Twins, and the Tigers. Projections from FanGraphs and Baseball Prospectus peg the Angels as better than those teams, which would seem to make them a less suitable surprise pick. On the other hand, have you followed the Angels since 2014?

At least one Ringer staffer has picked them to surprise in each of the past three springs, and the best the Halos have done during that time is last year’s 77 wins. That’s the wrong sort of surprise. Yet as much as I want to snap the cycle and pick Miami, I just can’t quit the team of Ohtani and Trout. I mean, imagine: a healthier Trout, Anthony Rendon, and Patrick Sandoval; full seasons from mid-2021 reinforcements Brandon Marsh, Jo Adell, and Reid Detmers; a better bullpen; a bounceback from David Fletcher; no sub-replacement play from Albert Pujols and Justin Upton; Noah Syndergaard, I guess? This is so the year. Lucy, please prepare to pull the football again.

Wagner: Tigers. Someone has to beat the Twins enough to turn them into 2022’s flop team! Detroit has languished in various states of tanking or mediocrity since their Dave Dombrowski–led push in the early 2010s. The Tigers made young pitchers the cornerstone of their rebuild. And while Casey Mize, Matt Manning, and Tarik Skubal figure to be important parts of the next Tigers team to make the playoffs, the lineup has ironically become the draw. I have no idea whether Akil Baddoo will re-create his 2021 season, or how Torkelson will perform as a rookie, whether and when Riley Greene will be called up, or even how Javier Báez will hit in the first year of a big contract. But if half of them perform like they’re capable of, this team will beat up on mediocre pitching all year and be surprisingly enjoyable to watch in the process.

Kram: Marlins. Besides the 60-game pandemic season, the Marlins haven’t finished with a winning record since 2009—before Giancarlo Stanton debuted—or reached the playoffs since 2003. But the club has real reasons for optimism, via a dynamic young rotation headlined by Alcantara, Pablo López, and Trevor Rogers, plus a lineup now stocked with competent position players like Stallings and Avisaíl García. I’m not actually predicting the Marlins will make the playoffs, but I think they’ll come close and finish ahead of one of the NL East’s big three. And if youngsters Jesús Sánchez and Jazz Chisholm take another step forward, they could be even better than that.

Baumann: Marlins. This is a really stupid thing to write seven months after the Giants wrapped up a 107-win season that came out of nowhere, but I’m going to do it anyway: I don’t know where a truly shocking good team is coming from this year. Clubs that might return to the playoffs this year—the Blue Jays, Mets, or Phillies—are big-market teams that spent a lot over the winter. A lot of the bottom third of the league is either rebuilding or telling everyone they’re rebuilding and just cashing revenue sharing checks. If the Mariners or Tigers make the playoffs, it won’t be totally unforeseen, just earlier than expected.

That leaves the Marlins, who have one of the best young pitching staffs in baseball even with Meyer in the minors, some exciting young talent elsewhere on the diamond (Chisholm, Sánchez), and just enough competent other big leaguers to win a lot of 4-3 games and scrape out 80-something wins.