October 27 will go down as the day the Los Angeles Dodgers converted their long-running regular-season success into postseason triumph and ended a 32-year drought between titles. It will also go down as the day Rays skipper Kevin Cash made an already infamous move, pulling starter Blake Snell in the sixth inning after the southpaw allowed just his second single—and second base runner—of the game.

If you’re bitter about what went down on Tuesday, you can call Cash robotic, inflexible, and overly beholden to a stat-centric script. But you can’t call him image-conscious or cowardly. There is zero reputational upside to taking out a cruising starter who’s held the opposition scoreless in a must-win game: The incoming reliever can only allow more runs than the pitcher he replaces. Yet Cash, knowing he would wear it if the Rays lost their 1-0 lead, pulled the 2018 Cy Young Award winner after just 73 pitches and replaced him with right-handed reliever Nick Anderson, who had allowed at least one run in six consecutive outings.

To call Cash’s quick hook “controversial” would make the response seem less one-sided than it was. This was the sort of decision the “Bold Strategy Cotton” meme is made for. And no, it didn’t pay off for him. The first batter Anderson faced, Mookie Betts, doubled, sending Austin Barnes from first to third. Then Anderson uncorked a wild pitch that allowed Barnes to score and Betts to advance to third. The next hitter, Corey Seager, bounced a grounder to first, and Ji-Man Choi’s throw home was too late to prevent Betts from scoring the go-ahead (and, it turns out, winning) run. Behind a succession of six scoreless relief appearances and an eighth-inning homer by Betts, the Dodgers won 3-1 and took the World Series four games to two.

After the game, Cash told reporters that he regretted the result, but not the thought process, and that he’d make the same decision again. He explained that he “didn’t want Mookie or Seager seeing [Snell] a third time.” Snell, perhaps saving his anger for an offseason Twitch stream, publicly supported Cash’s call, saying that while he thought he could get through the order again, Cash is “usually right” and that “there’s no pointing fingers.” But Kevin Kiermaier—the only Rays player who predates Cash’s time with the team—broke ranks to express what most fans were feeling: “I don’t care what the numbers say. There weren’t many guys that were making contact.” (Snell struck out half of the 18 hitters he faced.)

The point of this piece isn’t to tell you whether Cash, a leading contender for the AL Manager of the Year Award, was right or wrong—and let’s stipulate that when I say “Cash,” I mean whatever combination of coaches and quants arrived at the approach. The point is to put Cash’s choice in context, because his hook was the culmination of a postseason in which starters worked a lot less than ever before. And regardless of whether those early moves make sense on paper or in practice, I’m getting tired of them.

Let’s briefly review why Cash pulled Snell, because based only on Snell’s performance to that point in the game, it seems nonsensical. (You might say it’s nonsensical even after our review, but let’s lay it out anyway.) In his regular-season career, Snell has allowed a .592 OPS in his first time through the order, a .711 OPS in his second time through, and a .742 OPS in his third time through, with worsening strikeout-to-walk ratios. That’s a significantly steeper-than-average dropoff, but given a sufficient sample, virtually all pitchers suffer some version of this penalty. In 2019, MLB starters allowed a collective 111 tOPS+ their third time through the order—that is, they were 11 percent worse the third time through than they were overall. In 2009, that figure was 113, and in 1999, it was 111. (John Smoltz, who claimed on the Game 6 broadcast that modern pitchers suffer their third time through because they aren’t conditioned to pitch deep into games, posted a career 108 tOPS+ his third time through and a 136 tOPS+ his fourth time through.)

This issue stems more from familiarity than fatigue, so it doesn’t seem to matter much that Snell hadn’t thrown many pitches; Betts and Seager had still seen him twice. (For what it’s worth, Snell’s final fastball was his slowest of the night.) Betts was way worse against lefties than righties in 2020, but he faced them only 64 times, much too small a sample to be meaningful. Nor does it matter much, in a predictive sense, that Betts has hit .304/.370/.522 against Snell in his regular-season career—right around his career rates—or that he’d struck out swinging against him in his two trips to the plate on Tuesday.

Over the course of his career, Betts has has had about the same level of success against lefties (133 wRC+) as he has against righties (136 wRC+), and one would expect him to be worse against same-handed pitchers in the future, just as Snell has been a good deal better against same-handed hitters. (Over a long enough time frame, platoon splits are almost immutable laws.) Before Game 6, The Athletic’s Eno Sarris actually made the case that Betts was a particularly poor matchup for Snell because of Betts’s success against sliders and high fastballs, Snell’s bread and butter.

In this case, of course, Snell had looked great. But one of the most counterintuitive sabermetric discoveries is that pitchers deal until they don’t. A pitcher’s performance up to a particular point in a start doesn’t do a good job of predicting his performance in the rest of the outing, and while one would think managers and coaches could discern when a starter is or isn’t about to unravel, they don’t (on the whole) have that knack. We don’t have to look far to find an example of how fickle “cruising” can be: In Game 2, Snell held the Dodgers scoreless and hitless through the first four innings, racking up eight strikeouts. In the fifth, though, he allowed a walk, a home run, another walk, and a single before Cash summoned Anderson (who struck out Justin Turner to end the inning). Maybe Cash discounted vital evidence in front of his face on Tuesday. At times, however, it’s an act of helpful humility for a manager—and a former catcher like Cash—to accept that there are limits to his prognosticative powers.

The evidence above doesn’t make a conclusive case that Cash was right to pull Snell. But in a one-run elimination game, with the tying run on base, the second-best player in baseball up next, and the pitcher at a platoon disadvantage, “He was dealing” wasn’t enough of a reason not to. The more questionable call may have been trusting Anderson, who entered Game 6 with a 5.02 ERA in nine 2020 postseason appearances, along with an un-Anderson-like 9-to-4 strikeout-to-walk ratio.

By FIP, Anderson was the third-best reliever with more than 60 innings pitched over the past two regular seasons, but he hadn’t pitched like the person who compiled those stats since at least the ALDS. The Rays subscribed to the track record—or, perhaps, whatever proprietary systems they used to assess his stuff—instead of the iffy recent results. And while they were rewarded in Game 2 for sticking with a slumping Brandon Lowe, they were burned for their faith in Anderson in Game 6—not that Betts, who described seeing Snell lifted as “like a sigh of relief,” wasn’t capable of punishing any pitcher who opposed him.

For better or worse, this is how the Rays operate. In ALCS Game 7, Cash caused consternation by pulling Charlie Morton after 66 pitches with two outs in the sixth. Morton, too, had shown fantastic stuff while holding Houston to no runs and one hit through the first five innings. But in the sixth, he put runners on first and third, and Cash opted for Anderson rather than ask Morton to retire Michael Brantley for the third time. “I was as tense as anybody when Nick came into the game,” Cash confessed. But that time, Anderson escaped the jam. “It’s no discredit to anybody,” Cash said. “It’s just, that’s what we do. We believe in our process and we’re going to continue doing that.” He was true to his word.

Frankly, though, I wish he hadn’t been, even though the outcome may have bailed MLB out of another COVID crisis. We’ll never know if Snell, who hasn’t gone six innings in a start since July 2019, would have gotten two more outs before the Dodgers erased the Rays’ lead—or, if he had, whether the Rays would have shut out baseball’s best offense for three additional innings, which is what it would have taken to win on a night when the Rays’ offense was all Randy Arozarena. But it would’ve been fun to find out.

Last year’s World Series ended with a “would’ve been fun to find out” game, too. In Game 7, Astros manager A.J. Hinch pulled a dazzling Zack Greinke with a one-run lead after 80 pitches and 6 1/3 innings, calling upon Will Harris, who allowed a back-breaking, hard-luck homer to Howie Kendrick.

Last October generally offered a reprieve for starting pitchers, thanks to the Nationals’ rotation-reliant run to a title and one of the best rotation showdowns in World Series history. But the recent trend has been toward lighter and lighter workloads for starters, and Cash’s hook hammered that home. In their unending quest to find effective arms without paying premium prices, the low-payroll Rays have helped inspire the pursuit of short starts and openers. But it’s not as if the high-payroll Dodgers have bucked the trend; on average, only one Dodgers starter per season has qualified for the ERA title since 2016. L.A.’s Game 6 starter, Tony Gonsolin—who just this week was named by Baseball America as the publication’s Rookie of the Year—earned all of five outs before being yanked.

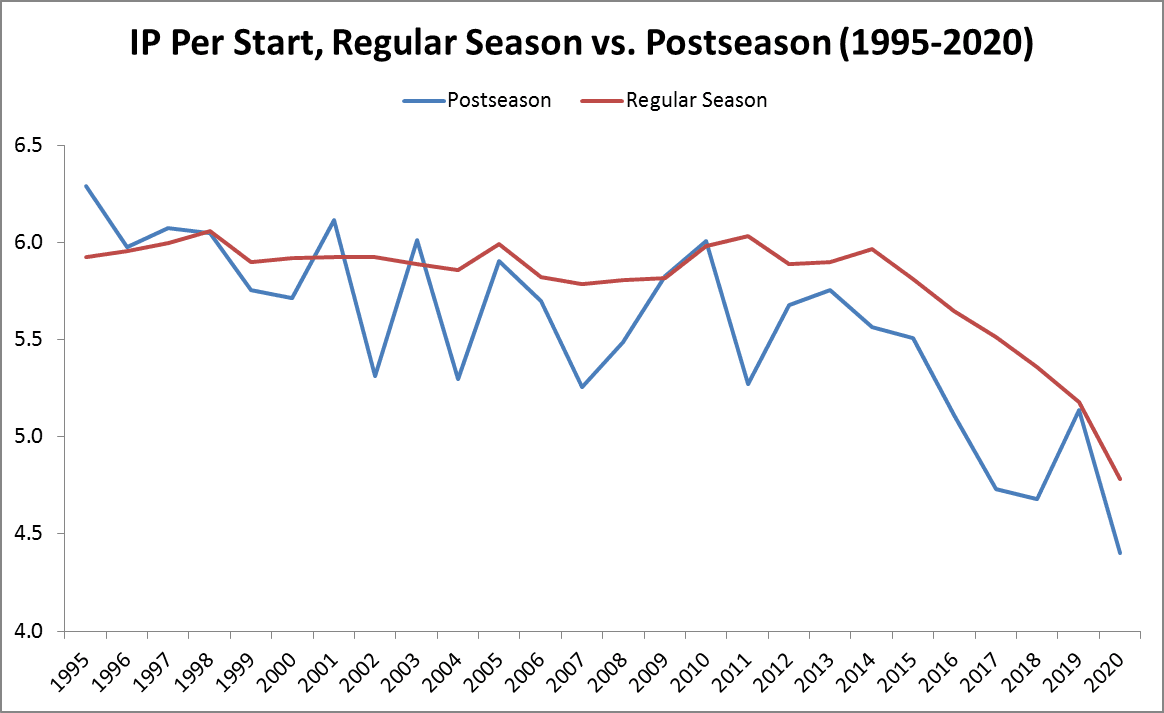

It’s tough to extrapolate pitching trends from the 2020 regular season, what with its compressed ramp-up to Opening Day, its elevated injury rate, its expanded rosters, and its seven-inning doubleheaders. In the postseason, though, the doubleheaders went away, and the pitchers—at least the ones who weren’t hurt—had built themselves up into typical midseason form. And while 28-man rosters remained in effect, giving managers more leeway with relievers, the lack of off days increased the incentive for starters to stay in. That’s not what happened, however: The average length of a postseason start fell just below 4.4 innings, a new playoff low.

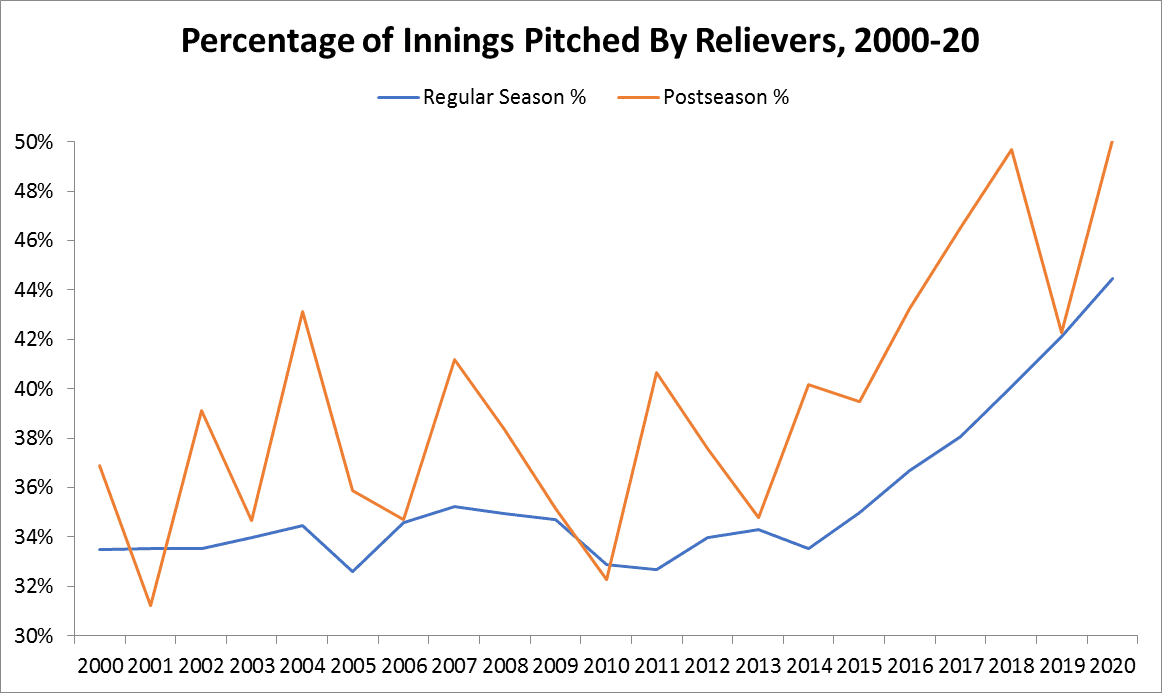

For the first time, relievers threw a tad more than half of all postseason innings.

In this reliever-oriented environment, the one-on-one postseason pitchers duel is essentially extinct. As Joe Sheehan noted in his newsletter on Friday, there was only one game this postseason (the 13-inning wild-card contest between the Reds and Braves) in which both starters went seven innings. That’s not new, Sheehan wrote: “There were three last year, all of which involved a Cardinals team that couldn’t hit. There was one in 2018, none in 2017, two in 2016. That’s seven in five years, even as the postseason is as large as it has ever been.”

It’s now almost unheard of for even a single postseason starter to go deep in a game. “It was Blake’s game,” Kiermaier said after Game 6, but no contemporary playoff game ever really belongs to one pitcher; the last October complete game came in 2017. In the first five years after the 10-team playoff format was implemented in 2012, there were an average of five eight-plus-inning starts per postseason. In the last four years, there were an average of only 1.25. This year’s 16-team playoffs featured 53 games, 15 more than in any other year, yet Clayton Kershaw was the only starter to last eight innings—and even his 93-pitch gem against the Brewers in the wild-card round was curtailed just short of all-time-great October territory.

More starters went 3 1/3 innings or fewer this postseason than went six innings or more. Some of those abbreviated outings are attributable to openers, but it’s getting hard to tell the difference between an opener and a starter who has a short leash. It’s not invariably better for fans from an entertainment standpoint if a starter goes deep in the game, but at this point, even the potential for extended outings is almost lost.

There’s a cost to closing off that avenue, one that manifests in more pitching changes and longer games; more strikeouts and dinger-dependent offense; and, less tangibly, less of an emotional investment in the men on the mound. As I wrote in 2018, “Each game tells a separate story, but the starting pitcher is always the best bet to be the protagonist.” Bullpenning may make sense statistically, but it deprives spectators of a constant figure to follow throughout the game. It’s optimal for teams, but less fun for us.

The transition from slow-hook Grady Little games to quick-hook Kevin Cash games has happened almost overnight. For a few years in the first half of the 2010s, “third time through the order” became a common refrain in October among analytically inclined media members, but that insight took time to filter to the field. Five years ago this Friday, I wrote, “By the end of October, writers are as tired of using our ‘third time through the order’ macros as you are of reading the results. But there is a penalty that affects every pitcher as he faces repeat batters multiple times (even with a low pitch count), so pulling the starter at the right moment is one of the most important postseason moves a manager can make. And many managers are still too slow with their hooks.”

The following year, October baseball became all about bullpens, and save for the blip last season, it’s proceeded further and further down that path. Front offices have gained a greater say over in-game moves, and the once far-fetched suggestions for openers and bullpen games that statheads used to blog about are now routinely implemented in win-or-go-home games.

One can’t realistically expect teams to go against their own competitive and/or financial interests for some nebulous good of the game. If we want teams to “let the players win or lose the game,” as Rays fan Dick Vitale tweeted (in all caps, of course) on Tuesday night, MLB will have to force them to ease off. The three-batter minimum is a Band-Aid on a compound fracture, and saving the starter would require a much more drastic step: for instance, strictly limiting the number of pitchers on each active roster, a measure FiveThirtyEight’s Nate Silver has suggested. Then again, that might not seem so drastic after the pandemic-imposed experimentation of 2020. This season’s rules were already supposed to include a cap of 13 pitchers on what were intended to be 26-man rosters. The league would just have to set the ceiling a little lower.

Cash was the goat in Game 6, but his fateful signal was a symptom of a widespread strategy that the Rays just rode to a pennant. In October, teams are taking that strategy to an extreme that’s often beneficial for them but deleterious to the sport. Narratively speaking, there’s something to be said for finding out if someone can dig deep for a few more miles per hour or a surprise off-speed pitch and get out of a mess of their own making. “I wanted to go the whole game,” Snell said. “That’s all I wanted to do, was empty the tank.” The Dodgers likely would have won anyway. But I would’ve liked to see Snell try.