The 76ers’ starting lineup has a new shape, but the new grouping is just as confounding as the old one. In the NBA’s Orlando bubble so far, Philadelphia has lost to a Pacers team missing its most valuable player this season, Domantas Sabonis, and needed a last-second Shake Milton 3-pointer to survive against the worst Spurs team in a quarter-century. If the 76ers were aiming for a roaring restart, with Ben Simmons now healthy and playing forward and the team as a whole months removed from its midseason malaise, that hope vanished around the time T.J. Warren passed the 50-point mark for the Pacers on Saturday.

And yet, as the franchise’s third postseason appearance in the post-Process era approaches, it’s still impossible to ignore a team led by Simmons and Joel Embiid, to stop dreaming about their potential to rampage through a playoff bracket. The 76ers can conceivably lose in the first round or reach the Finals. While other teams in the bubble scramble just to make the playoff field, the 76ers’ concern is more existential: Can their talent prevail in the next two months when it’s failed to this point so far?

The 76ers boast an undeniably impressive rotation. They lost Jimmy Butler over the summer but added Al Horford and Josh Richardson and retained Tobias Harris; together with Simmons and Embiid, they formed—on paper—an unimpeachable starting lineup. Their preseason over/under betting line was the second highest in the league, behind only the Bucks, according to Basketball-Reference, and opposing GMs ranked the 76ers the second-best team in the East. Even now, after a winter of discontent that saw the team start 20-7 but go just 19-19 thereafter, FiveThirtyEight’s main predictive model thinks that if every team plays at full strength with a postseason rotation, the 76ers are just as good as the Bucks, and better than the Raptors, Celtics, and other Eastern Conference contenders.

But their results haven’t matched that potential. Philadelphia is currently the no. 6 seed in the East, and that placement is not a fluke. The team’s record is 40-27; its Pythagorean record, measured by point differential, is 38-29. The 76ers rank in the bottom half of the league in offensive rating, and only seventh on defense—a disappointment given preseason expectations.

Put another way: The 76ers have a worse point differential than teams like the Pacers and Thunder, and nobody really thinks of those teams as dark-horse Finals contenders.

History casts doubt on the team’s chances this postseason, too. In the 16-team playoff era (which dates back to 1984), the worst regular-season team to win a title was the 1994-95 Rockets, which outscored their opponents by the same amount as these 76ers: 2.1 points per game. No other champion comes close. Only six of 36 champions had a regular-season differential below five points per game.

Worst Regular-Season Teams to Win a Title (1984-Present)

Squint and it’s possible to see the outline of a comparison between the 1994-95 Rockets and the 2019-20 76ers, two teams with dominant centers playing in seasons without a clear favorite (a rusty Michael Jordan, just returned from his baseball sojourn, in 1995; no Warriors in the 2020 bracket).

But few teams in NBA history have managed to flip the playoff switch after scuffling through the regular season. And the groups that did successfully pull that trick had already proved their playoff bona fides by winning a title: those very 1994-95 Rockets, for instance, or the 2000-01 Lakers, or the 2017-18 Cavaliers, whose regular-season point differential of 0.9 points per game is the worst for any finalist in the 16-team era. Those Cavaliers also had LeBron James. These 76ers don’t.

Broadly speaking, basketball teams are about as good as the sum of their parts. That doesn’t mean fit, team philosophy, or style don’t matter, but über-talented players tend to make any situation work. Folks were concerned about the Rockets when they added Chris Paul—the old “so many players, just one ball” canard—only for Houston to win 65 games with one of the most efficient offenses in league history. Yet Philadelphia is an exception: It has too many non-shooters among its five best players to make a modern offense whir.

When Simmons, Embiid, and Horford share the floor, the 76ers allow just 99.9 points per 100 possessions, per Cleaning the Glass, which ranks in the 98th percentile of lineup combinations this season. Yet the trio gives back all those gains on the offensive end, where it scores just 99.2 points per 100—ranking in the third percentile of lineups.

The 76ers have played well when Simmons shares the floor with Embiid (plus-6.1 net rating) or Horford (plus-6.0), but not when he shares it with both. The new rotation, with Milton joining the starting lineup and Horford moving to the bench, is designed to separate Embiid’s and Horford’s minutes as much as possible while adding another shooter.

76ers’ Lineup Performances

That approach could work in theory, and it has the side benefit of putting Horford on the floor to stabilize the defense whenever Embiid is off. Those minutes were the team’s doom last postseason; in seven games in the second round, the 76ers outscored the Raptors by 90 points in Embiid’s 237 minutes, but were outscored by a gobsmacking 109 points in the 99 minutes he sat.

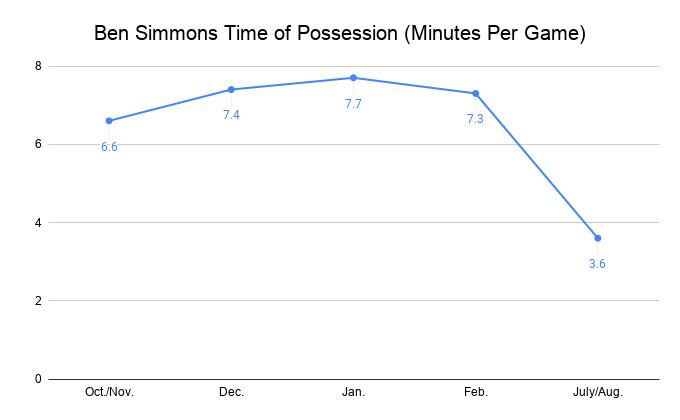

That approach also shifts Simmons off the ball more. In the two bubble games, he’s held the ball for only half as long as he typically did earlier in the season. Whether that change is effective remains to be seen, however—Simmons is a fine distributor in his own right, with a career average of eight assists per game, and it’s possible that the move crowds Embiid’s position near the basket even more. Simmons might be a power forward now, but suffice it to say he is not a stretch power forward.

On the other end, the insertion of Milton adds an obvious weak link to an otherwise stout defensive group. If the 76ers advance a few rounds this summer, their defense will lead the way. The team almost seems built with Giannis Antetokounmpo in mind, with Embiid, Horford, and Simmons all options to throw at the presumptive MVP.

And although the 76ers were 12-18 against teams with a .500 record or better pre-bubble—the worst mark for any team in the East’s top six—they offered glimpses of their potential against elite opponents. They beat the Bucks on Christmas, pouring in 21 3-pointers in a blowout win. They beat the Celtics—a potential first-round opponent—in three out of four meetings. They beat the Clippers and Lakers, the latter without Embiid.

FiveThirtyEight publishes predictions using two different models: a main one based primarily on individual player talent ratings, and an alternate one based primarily on collective team results. The player-oriented model favors the Sixers more, giving the team a 28 percent chance to reach the Finals and an 11 percent chance to win the title; the team-oriented model is at 2 and less than 1 percent, respectively. (The Ringer’s NBA Restart Odds, which hew more to the team-based side, put the Sixers’ Finals and title odds at 0.8 and 0.2 percent, respectively.)

But the converse is true for the Bucks and Raptors, who both see their odds drop in FiveThirtyEight’s player-oriented model. Thus the gap shrinks in both directions: The 76ers are more talented than their record suggests, while the Bucks and Raptors are less talented than their records suggest. “In the talent ratings, Milwaukee and Philly are essentially tied, the Celtics are not far behind at all, and the Raptors are just decent,” says FiveThirtyEight’s Neil Paine. “In other words, the two best teams [in the team-based model] look worse and the next two look better, creating these weird splits.”

The Raptors’ pieces all seem to fit together in a way the Sixers’ don’t; add in stylistic flexibility, some Nick Nurse magic, and the swagger of having won a title last season, and it’s easy to see how the Raptors could overperform their collection of pure talent. The 76ers look like the reverse, at least to this point.

They can get on the right track before the playoffs, particularly while adjusting to the new rotation. Early returns are inconsistent, befitting the team at large. Milton sank the game-winner against San Antonio as part of a 16-point game; against Indiana, however, he tallied zero points, three turnovers, five fouls, and one public argument with Embiid. Simmons did the reverse, posting strong numbers against the Pacers before fouling out after just eight points against the Spurs. Horford had a plus-minus of negative-26 in the first game, then swung to positive-17 in the second.

But ultimately, there won’t be much more to learn about how the 76ers might fare against the East’s best teams before the playoffs begin. Their next four games come against the dilapidated Wizards, Magic, Trail Blazers, and Suns—all worse teams than Philadelphia will play in the first round of the playoffs, let alone the second or third or fourth. Even a team with the most raw talent would struggle to defeat the Celtics, Raptors, Bucks, and an L.A. team all in a row.

The 76ers were just as erratic last season, all the way up to their playoff elimination. They lost in a 36-point blowout in Game 5 against Toronto, catalyzing premature obituaries, before winning Game 6 and coming within a Kawhi Leonard miracle of forcing overtime in Game 7. They might forever lament that missed opportunity, especially if this season’s struggles extend to the playoffs, or set them up in a bracket position too difficult to navigate even if the new lineup works as hoped. There’s no guarantee that young teams will get better season after season. Sometimes they plateau or never turn all that promise, and all that talent, into actual results on the court.