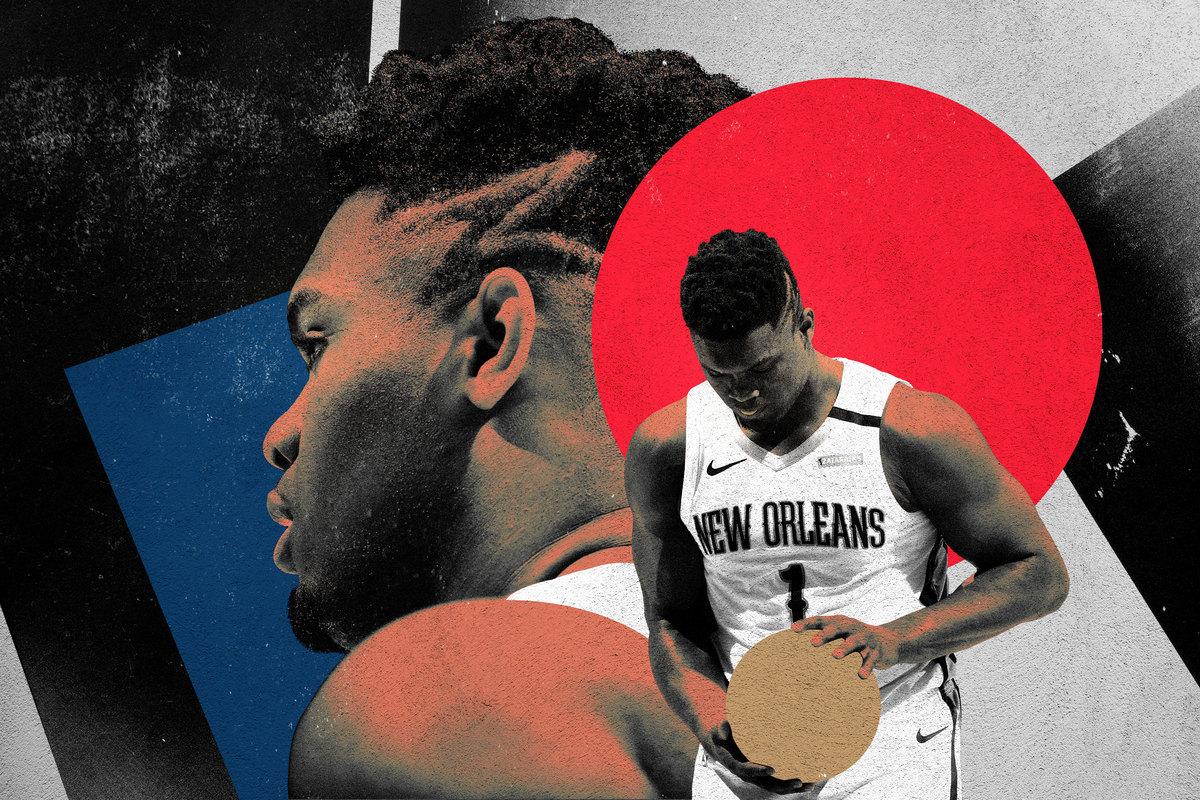

The possibility of Zion Williamson living any kind of normal life melted away years ago, under the blistering hype of YouTube mixtapes. Now, just 19 games into his professional career, he doesn’t even have the luxury of being a typical, workaday superstar.

When the NBA formulated an ambitious, unprecedented plan to continue its season amid a global pandemic, at considerable risk and despite staggering complexity, it seemingly did so with Zion in mind. It would have been safer for the league to invite fewer teams and play fewer games by jumping straight into the playoffs. Instead, they designed a format that included Williamson and the Pelicans, who rank 10th in the West, while conspicuously introducing a play-in mechanism that would allow New Orleans to compete for a playoff spot.

Coaches and executives with other teams will matter-of-factly explain that Zion is the reason the restart is structured this way. He is a critical figure for the NBA at a precarious time in its history. The inability to draw crowds to arenas has destabilized the economic model of the entire league; beyond losing hundreds of millions of dollars in ticket sales, NBA teams will also take hits from the lost opportunities to sell concessions, suites, and in-arena sponsorships. As players in the bubble move into the seeding phase of the restarted season, NBPA executive director Michele Roberts has considered whether next season will be possible without similar accommodations. “If tomorrow looks like today, I don’t know how we say we can do it differently,” Roberts told ESPN.

The NBA, while diligent enough to prevent any positive tests within the bubble itself, is also clearly looking forward. The first meaningful game played in Orlando was planned to feature Williamson and the Pelicans, allowing the rookie sensation to make the league’s formal reintroduction. It doesn’t require especially complicated analysis to understand why. Zion is enormously popular; he had one of the 15 top-selling jerseys in the league this season. Still, there’s a difference between highlighting Williamson’s play and making him one of the faces of the NBA restart. The rookie stands front and center in league marketing materials, shoulder to shoulder with the likes of James Harden and Giannis Antetokounmpo.

Zion is positioned that way in part because his play warrants it (an incredible development for a player who hasn’t yet played 600 minutes), but also because the league needs him to be. In some ways, the NBA product has never been more popular. Sports fans now carry the game with them wherever they go, doled out in highlights as they scroll through their phones. Players themselves have become a part of our daily feed. It has never been easier to watch a regular-season NBA game, whether from across the country or around the globe. All of that is complicated by metrics that indicate the number of people actually consuming the NBA games is in obvious decline. Every device that can be used to stream an NBA game can also be used to watch movies, play games, or otherwise fall deeper and deeper into the pit of idle, mind-numbing entertainment. Superstars appear to be the exception. The league’s formula is predicated on the idea that viewers will make time for LeBron, which both carries the NBA in the present and underlines the need for an eventual successor.

These were the dynamics before a pandemic called into question every dollar the NBA makes. The very existence of the bubble is proof of another level of urgency. Procedurally speaking, the league wanted to finish its season and crown a champion. It also needed to fulfill certain contractual requirements and wanted to put live sports in front of a somewhat captive audience. When The Last Dance aired back in April, it drew 5.8 million viewers on average—more than the vast majority of first-round playoff games. There is crossover appeal whenever Michael Jordan is concerned, though the same could be said of any new sporting event right now. The NBA playoffs, if the league can successfully manage them, would be a cultural experience.

When given the potential for that kind of audience, the NBA first created a competitive framework that would allow Zion to participate, and then scheduled it to make him the first thing audiences see when games continue in earnest. The top contenders and the defending champions will have to wait. Leading off the NBA’s official comeback is a small-market bout between the New Orleans Pelicans and the Utah Jazz, anchored by an imminent superstar. This of course assumes that Zion plays in the game at all; Williamson is one of several NBA players to have left the NBA campus to attend to urgent personal matters. “I was dealing with a family emergency,” Williamson said. “It’s God first, then family. Basketball wasn’t really there. I was dealing with something serious.” To preserve even the possibility that he would be available for the opening game, the Pelicans and the NBA made arrangements for Williamson to be tested for the coronavirus daily while away, shortening the mandated quarantine upon his return.

Excused absences like the one granted to Williamson reinforce how much the remainder of the NBA season relies on what happens outside the bubble. League officials took great care to create a regulated campus environment with layers upon layers of safeguards to prevent the spread of the virus. Yet three members of the Clippers—a team that could wind up winning the title—have already left the bubble for personal reasons, including one who took an already legendary detour to a strip club for chicken wings. Boston’s Gordon Hayward, Utah’s Mike Conley, and Brooklyn’s Garrett Temple have already expressed their intention to leave the bubble to attend the birth of their children. There is so much at stake for the NBA, and yet the league can control only a few hotels, a few arenas, and the space in between. Zion could have taken every precaution while on leave and still come into contact with the virus. Even if the NBA caught his hypothetical infection before it compromised the integrity of the bubble, it still would have upended the best-laid plans to showcase a league ambassador-in-waiting.

The pressure created by Zion’s exit and return to the NBA bubble revealed how much the league already relies on the prospect of his stardom. This is an unreasonable burden—the kind that makes the pressure of revitalizing an entire franchise seem quaint by comparison. “I think we’ve gotta be a little bit careful about adding all these extra things on his shoulders,” said Pelicans coach Alvin Gentry. “He’s here to play. He’s here to have a good time.” A player like Zion, however, drafted first and fêted as he was, must know that he’s not just in Orlando to have a good time and push his team to the playoffs. Every game he plays is for the future of the league.