MLB Is Trying to Get a Grip on Foreign Substances. What Does That Mean for Pitchers?

Pine tar, sunscreen, rosin, shaving cream—they’ve all been illicit tools at many pitchers’ disposal. But the league says it’s cracking down on their use. If MLB is serious, we may see a ball that behaves very differently—both coming out of a pitcher’s hand and off the end of a bat.“After 15 years of facing [pitchers], you don’t really get over them. They’re devious. They’re the only players in the game allowed to cheat. They throw illegal pitches, and they sneak foreign substances on the ball.”—Hall of Famer Richie Ashburn, 1975

Of all the ways in which Major League Baseball will look different during the pandemic, the most whimsical is the wet rag. According to the health and safety protocols in the league’s 2020 operations manual, “All pitchers may carry a small wet rag in their back pocket to be used for moisture in lieu of licking their fingers.”

“Wet rag” is, of course, a very funny phrase, although the rag is around for a serious reason (reducing the spread of disease). Like any rule in sports, though, the wet rag regulation exists to be exploited and could produce unintended consequences more serious than swamp butts. MLB knows that not everyone can be trusted to use their wet rag responsibly, which is why the manual lays down the law. “Pitchers may not access the rag while on the pitching rubber and must clearly wipe the fingers of his pitching hand dry before touching the ball or the pitcher’s plate,” the protocols specify. “Umpires will have the right to check the rag at any point.” The manual also stipulates that “water is the only substance allowed on the rag.”

When I informed a former major league pitcher who now works for a team—let’s call him Deep Throwt—of the rag’s arrival, he questioned my facts, texting, “A wet rag? Really? This must be fake.” When I explained that the very real rag must be doused only in water, more mirth followed. “Hahahahahahahahahahahaha,” he said. “Yeah, water will be on that rag. Hahahahahahaha.” Deep Throwt is not former reliever Jeff Nelson, who expressed the same sentiment on Twitter with 19 fewer “ha”s.

An MLB official had no “ha”s for me either when I inquired about Nelson’s tweet. The rag really will be checked by umpires, the source said—maybe by wringing it out?—and any pitcher found to have violated the water-only order will deserve the harsh penalty he’ll receive. Furthermore, the source suggested, MLB will monitor Statcast spin rates and movement for any hint of a pitcher packing a rag that’s wet for the wrong reasons. Dramatic deviations from a pitcher’s baseline spin could indicate the presence of a prohibited substance, and could conceivably trigger a warning or closer scrutiny.

Ramping up efforts to prevent illegal pitching chicanery was a focus for MLB this season even before the threat of Trojan rags arose. In February, MLB promoted Chris Young to senior vice president, a role in which he oversees issues that affect play on the field, including standards and discipline, rules and regulations, and umpiring. Weeks later, Young—a former pitcher who spent 13 years in the majors—sent a memo to teams reminding them of the rules governing foreign substances on the ball, 3.01 and 6.02(c). He also reiterated the potential punishments for players caught using such substances (ejection and suspension) and laid out teams’ responsibilities to avoid aiding players in skirting the rules, as well as their obligation to disseminate the warning. Young, who declined to comment for this story, also spoke to teams directly during visits to spring training. The memo, which was obtained from a club, is embedded below.

The memo made clear that the underlying rules and enforcement strategies were staying the same, stating, “Under our practice, umpires are instructed to enforce the rules when they personally observe a potential violation or are informed of a potential violation by the opposing team. We do not intend to change that practice in the 2020 season.” In other words, it doesn’t seem as if umps were about to start conducting random spot checks or regularly patting down players, provided they stayed more subtle about their sticky substances than the Yankees’ Michael Pineda was in 2014, when he was caught sticky-handed and suspended for 10 games thanks to obvious streaks of pine tar on his arm and neck.

One team executive I spoke to pre-pandemic thought the memo was mostly hot air. If umpires were fully empowered to examine and prosecute pitchers, he said, 80 percent of offenders could be caught, but, “Managers are on the hook for policing it, meaning no shot anything gets done.”

Even so, another team source told me, “We’re going to assume they’re trying to look for everything. Anything and everything and every possible way. I don’t know if they even can, but I wouldn’t be surprised if they tried to go through locker rooms.” A week after MLB circulated Young’s memo, something got done: The Angels fired a longtime visiting clubhouse attendant after MLB reportedly informed the team of allegations that he had been selling “a melted-down pine-tar solution and rosin” to opposing pitchers. His behavior, which the Angels confirmed, violated the league’s policy against team personnel “providing, applying, creating, concealing, or otherwise facilitating” the use of foreign substances by players. That discipline sent a signal, but because of the benefits and the prevalence of foreign-substance use, the practice may prove as tough to remove from the sport as pine tar from fingers.

Generations of pitchers in the pre-rag era employed foreign substances, which we now know with some certainty enhance spin and movement. The possible smoking spin rates came courtesy of Trevor Bauer. Late last August, mired in month five of an inconsistent, confounding campaign that he later blamed largely on lousy luck, a bad back, and a bum ankle, Bauer bottomed out. On August 25 and 31, against middling lineups in Pittsburgh and St. Louis, the Reds starter allowed a total of 14 runs over seven innings, walking five batters and hitting one. His combined game score in those outings was worse than in any previous two-start stretch of his career, and he ended August with his highest monthly FIP since July 2016.

As September began, Bauer was a month into his tenure with a new team, less than a year removed from an expectations-raising season in which he’d finished sixth in AL Cy Young voting (and likely would have ranked higher if a comebacker hadn’t broken his leg), and a little more than a year away from free agency. Those ugly late-August starts may have made him look for a helping hand (or, as we’ll soon see, perhaps a helper on his hand). Alternatively, they may have convinced him that he was ready to write off the lost season and use the remaining month to make a point.

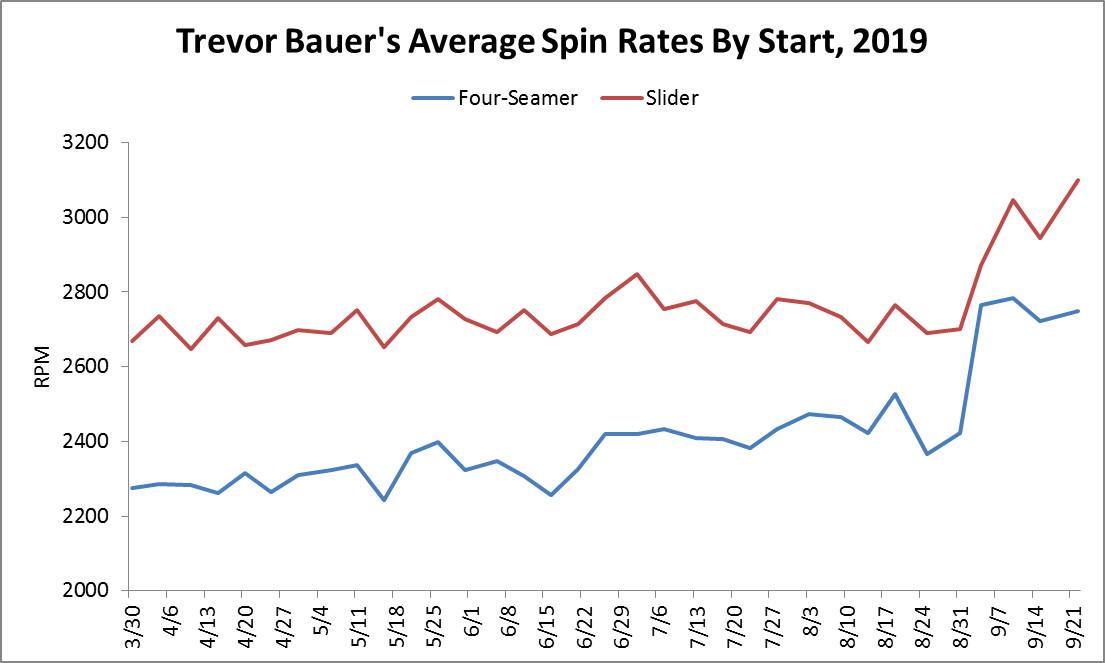

“He’s already gearing up for things he knows he’s gonna need to do to take his game to the next level,” Reds skipper David Bell said a few weeks later. Bell was referring to Bauer’s winter training regimen, but by late September, Bauer may already have leveled up in one way. As noted on the Effectively Wild Reds season preview podcast and in a FanGraphs post by Ben Clemens, Bauer’s spin rates spiked suspiciously last September. (“Suspiciously” is an understatement.) The graph below plots Bauer’s average four-seamer and slider spin rates by start. His four September starts stand out significantly from his previous starts in that season—and, for that matter, in the four preceding seasons.

Through August, Bauer ranked 54th in average four-seam fastball spin rate among the 161 pitchers who had thrown at least 500 heaters in 2019—solidly above average, but hardly elite. Among the 153 pitchers who threw at least 100 four-seamers in September, Bauer ranked first.

A leap of that magnitude isn’t just abnormal; it’s unprecedented in the five-season Statcast era. The table below, generated with assistance from Bill Petti of The Hardball Times, lists the biggest month-to-month increase in four-seam fastball Bauer Units since 2015 among pitchers with at least 100 four-seamers thrown in each month. The Bauer Unit—naturally, named after Bauer—is a metric introduced by Driveline Baseball (the offseason facility that Bauer frequents) to place the spin of pitches thrown at varying velocities on the same scale.

Fastball spin rate tends to scale linearly with velocity, so in general, the faster the pitch speed, the higher the spin rate: If two heaters have the same spin rate but one averages 92 mph and the other 96, the one with the lower velocity boasts the more impressive spin. Bauer Units divide spin rate (in RPM) by velocity (in MPH) to produce a normalized number. Bauer’s spin rate increased by more than 300 RPM (from 2455 to 2757) between August and September, despite a slight speed decrease (from 94.4 to 93.6). Do the division, and you get a gain of 3.44 Bauer Units, almost twice the size of the next-biggest bump on record.

Biggest Month-to-Month Bauer Unit Increases (Min. 100 Four-Seamers)

An outlier like that is highly unlikely to be natural. Even more eyebrow-raising, 22 of the first 23 pitches Bauer threw in his first September start—and 30 of the first 34—were four-seamers, as if Bauer wanted to test his new spin superpowers. (As Driveline founder and current Reds director of pitching initiatives Kyle Boddy wrote in a now-deleted 2018 tweet, sticky substances are most effective at enhancing the spin on a four-seamer or slider.) Reds reliever Michael Lorenzen, who quickly bonded with Bauer after the latter was traded to Cincinnati, also boosted his spin rates (albeit more modestly) over the same span.

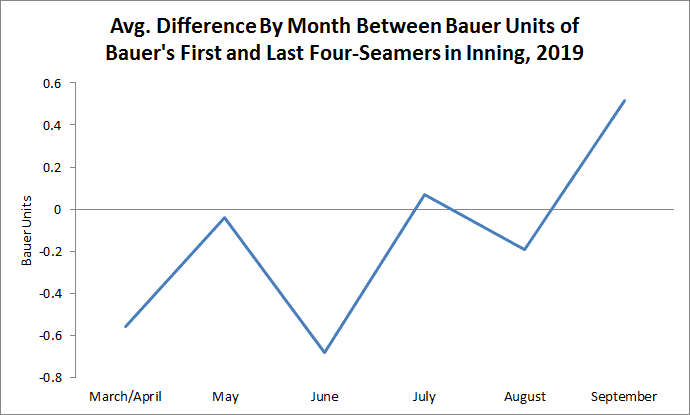

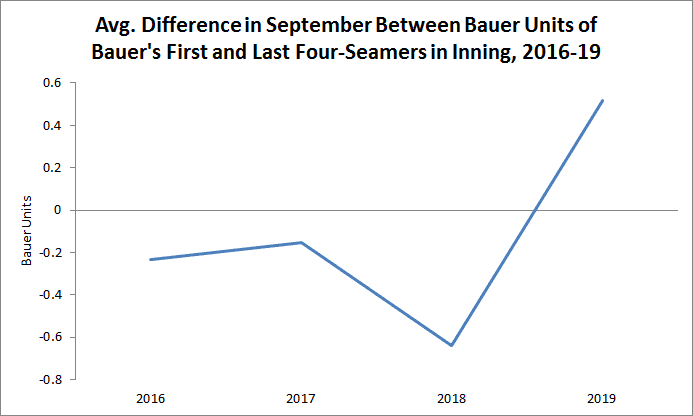

A final piece of evidence: Bauer’s fastball spin, as measured by Bauer units, has historically been lower at the beginning of innings (with at least five four-seamers thrown) than at the end. Last September, though, his spin was a good deal higher at the start of his innings, which could indicate—per his own past tests—that he was applying a topical cream liberally at the beginning of innings but that the effect was wearing off by the end. The same reversal was evident in his September intra-inning spin difference compared to the previous three Septembers.

Bauer declined a request in spring training to talk about foreign substances, and Boddy declined to comment too. Aside from a March 7 tweet that appeared to allude to his supercharged spin, Bauer hasn’t publicly acknowledged the change. But he’s said (or tweeted) so much on the subject before that his old words will do.

As Bauer wrote in February in a piece for The Players’ Tribune about the Astros sign-stealing scandal, “For eight years I’ve been trying to figure out how to increase the spin on my fastball because I’d identified it way back then as such a massive advantage. I knew that if I could learn to increase it through training and technique, it would be huge. But eight years later, I haven’t found any other way except using foreign substances.” If we take him at his own word, then, that spike in September must have stemmed from those substances, which are banned by MLB.

Bauer has been outspoken about the impact of prohibited topical substances on pitch performance since 2018, when he accused the Astros of using sticky stuff to inflate their rates.

Asked about the outburst, Bauer explained that his Twitter contentions about the performance-enhancing effect of sticky substances were based on testing he and others had done in the Driveline lab. “I’ve tested sunscreen and rosin,” he said. “I’ve tested pine tar sticks. I’ve tested the liquid pine tar. I made my own non-Newtonian fluids. I sat down with a chemical engineer to understand it. I’ve melted down Firm Grip and Coca-Cola and pine tar together. I’ve tested a lot of stuff.” (Early this year, he speculated that the Astros may have used some of the same substances in games.) His conclusion was that the use of such substances at game speeds could enhance spin by 200-300 RPM—roughly the boost he received last September. (My MVP Machine coauthor Travis Sawchik observed similar results on a visit to Driveline.) As Bauer once tweeted:

This isn’t even the first time that Bauer has seemingly taken sticky stuff for a test drive in a game. On April 30, 2018, not long after casting aspersions on the Astros, Bauer boosted his average spin rate by almost 300 RPM in the first inning of a start. After that, his rates return to normal. The Athletic’s Eno Sarris drew attention to the increase, and Bauer stopped just short of confirming the experiment when reporters asked him to elaborate. “I have no comment about that,” Bauer said. “I think Eno Sarris wrote a great article about it and explains things pretty well. So, read his article.”

I asked pitching strategist Michael Augustine to provide pitch overlays of examples of Bauer’s regular August fastballs and sliders and his spin-enhanced September fastballs and sliders. Here are the heaters:

And here are the sliders:

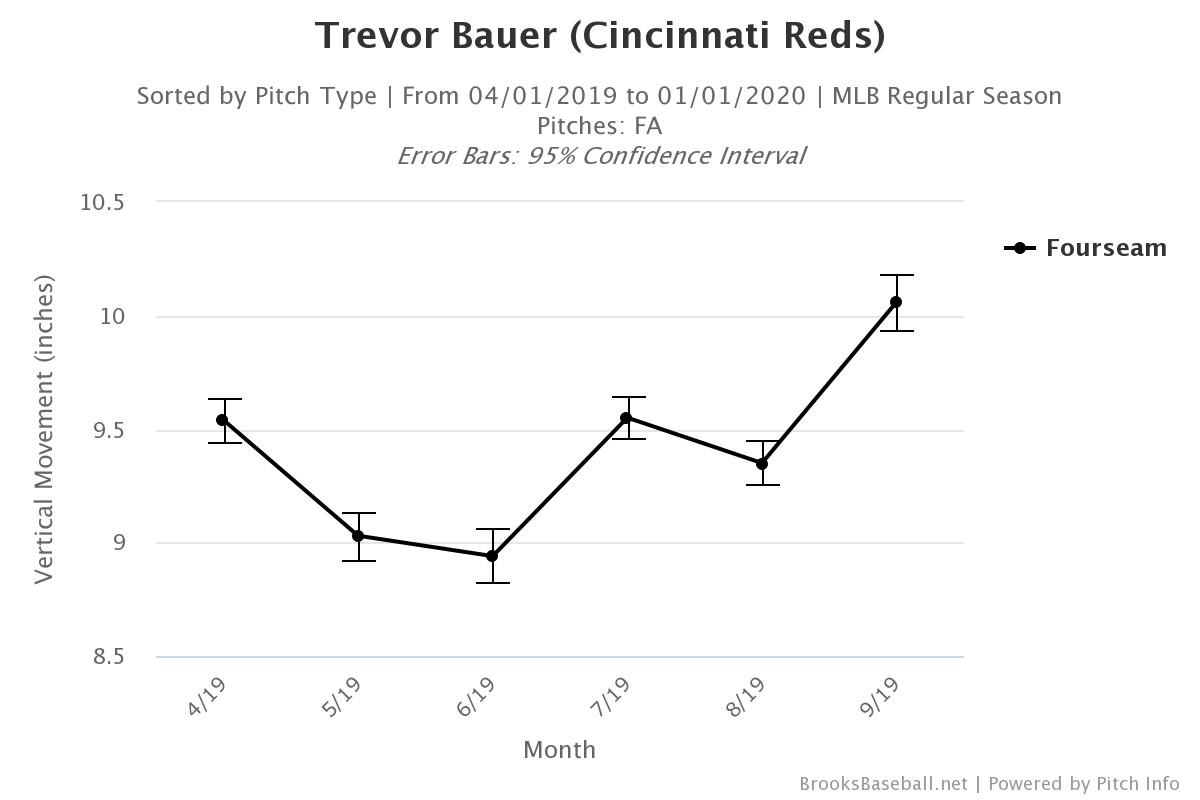

The offset center-field angle makes the movement difference seem somewhat more dramatic than it would have to the hitter, but one would expect to see more “rise” and break after a spin jump so big, assuming the spin is transverse (perpendicular to the direction of movement) and directly translates to movement. According to Clemens’s calculations at FanGraphs, Bauer’s was. Bauer is particularly adept at harnessing his spin to create movement, and his pitches did move more in September, just as they had in his anomalous inning in 2018.

Bauer was hardly unhittable that month, but he did post by far his highest strikeout minus walk rate of any month last year (albeit without a corresponding surge in whiff rate). And if he could raise his rates so suddenly, then any pitchers who’ve been using something similar may already be deriving a comparable rate hike. Which raises a compelling question: What if that edge went away today? How much would it help hitters in an era when whiffs are ascendant?

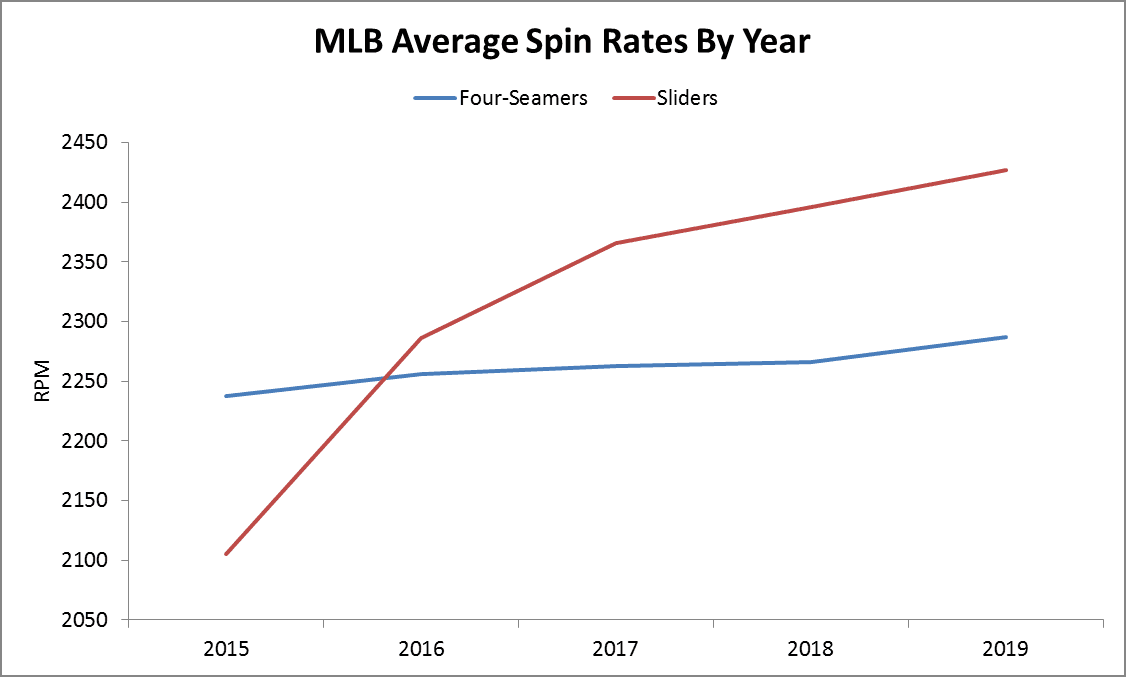

Bauer has repeatedly said—not only on Twitter, but in a February appearance on HBO’s Real Sports—that he believes the use of sticky stuff is a bigger advantage than steroids. As the table below shows, hitters in 2019 did less damage when they made contact, and also made contact less often, as four-seamer and slider spin rates (on average, 2287 and 2428 RPM, respectively) rose.

2019 Four-Seamer and Slider Effectiveness by Spin Range

“I certainly believe that adding some sticky substance to the surface of the ball (or to the fingers) can result in more spin,” says professor Alan Nathan, a baseball physics expert. Bauer’s stated goal isn’t to eradicate the use of foreign substances, but to convince MLB to legalize and standardize it, which he believes would level the league’s playing field. He’s maintained that he doesn’t want to cheat, although he believes that about 70 percent of other pitchers are flouting the foreign-substance rules. For The MVP Machine, Bauer told Sawchik, “At the end of the day, I want to know that everything I achieve is 100 percent me,” and on Real Sports, he denied having used foreign substances in games.

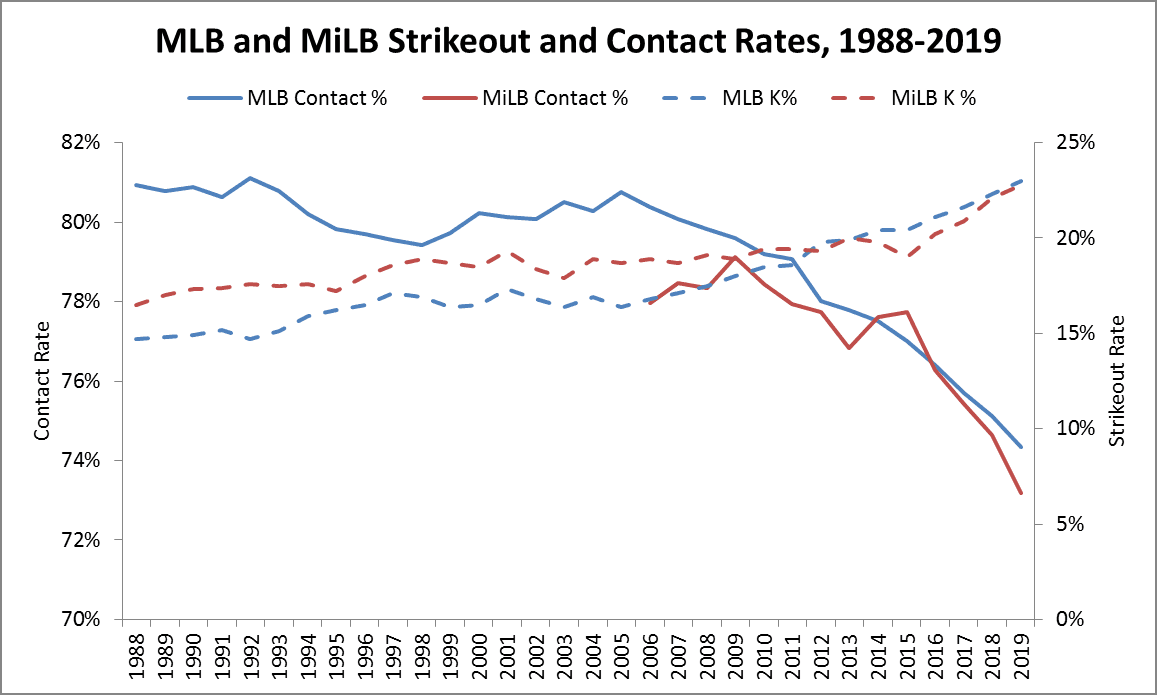

What the truth about Bauer’s use of sticky stuff, the attention he’s brought to the issue—via his apparent in-game demonstrations, his public comments, and his face-to-face meeting with commissioner Rob Manfred in March—may have helped put pressure on MLB to keep its players in line at a time when the league is licking its wounds from failing to crack down on illegal sign stealing before it left its latest stain on the sport. As of spring training, though, the games were more whiff-filled than ever: When exhibition action was suspended, the combined Cactus and Grapefruit League strikeout rate stood at 24.1 percent, up from 22.3 percent last spring and 23.0 percent last regular season.

No players I surveyed seem to disagree with Bauer’s estimate that 70 percent of pitchers are using foreign substances that are technically disallowed—unless it’s to say that 70 percent seems low. “If they start to crack down on it there will be so many suspensions, unfortunately,” says one MLB pitcher. “We all know the number of players who use it is easily above 70 percent. After the Astros scandal this would just make MLB look even worse, in my opinion.”

Then again, not suspending players involved in the sign-stealing scheme was part of what made the league look so bad. One important purpose of the memo appears to be covering MLB’s ass in the event of a foreign-substance scandal. The last paragraph makes it clear that the clubs are responsible for spreading the word about banned ball-doctoring to the many interested parties on their pitching staffs.

“I used some form of sticky grip every single game of my professional career, and most of my college career as well,” says Jonathan Perrin, a 27-year-old former pitcher who’s able to speak freely about a somewhat taboo topic because he recently retired from baseball to become a full-time investment adviser. Perrin pitched in the Brewers and Royals systems, topping out at Triple-A. “The vast majority of pitchers are using something to help them get a grip on the ball,” he continues. “If you watch just about any game on TV, you’ll see pitchers dabbing their fingers on their forearm or on one of the fingers on their gloves. That’s not a nervous tick, that’s guys going to get a little stick so they can get a better grip for the next pitch. If MLB really wanted to crack down on it, all they would have to do is watch the games, see areas that pitchers are repeatedly going to with their pitching hand in between pitches, and then buzz an umpire to go check that spot. More times than not you’d find something sticky there.”

As Perrin pitched more often in televised games, it got harder to hide Pelican Grip Dip or pine tar (which can gum up a pitcher’s hands), so he switched to Tyrus Clear Sticky Grip or sunscreen and rosin, which are clear and tough to see from afar, though not entirely undetectable. “If you walked up and looked at it really close you could tell,” he says. “And if you touched my glove I’d be gone. I would say sunscreen and rosin on the forearm is the hardest to detect, virtually invisible. Even if you’re looking closely, you’d have to actually touch the guy to know.”

Deep Throwt says his sticky experience was similar to Perrin’s, although he didn’t become a connoisseur in college. “The first day that I was in pro ball, people offered me pine tar,” he says. “I said, ‘Why?’ They said, ‘Because it makes your ball move more.’ I get to the big leagues, and then there was a plethora of different objects and ways to manipulate the ball and different substances. I mean, I have 30 choices sitting in the bullpen of different things. Trainers would talk to me about what to use and how to use it.”

One difference in earlier decades, Deep Throwt says, is, “We just didn’t have the data.” He and his teammates intuited that sticky stuff worked, but without pitch-tracking technology, they couldn’t quantify the effect or exploit it further by throwing high-spin fastballs up in the zone, where they tend to be most effective. The same ball-tracking tech that has highlighted hidden dimensions of catcher framing or fluctuations in the ball has increased the emphasis on measuring and maximizing spin, which has in turn exacerbated baseball’s contact problems. Average four-seamer and slider spin rates have climbed in every season since Statcast was installed.

Now that we know precisely how the ball is behaving, we can longer ignore its fluctuations in flight from month to month and season to season. Similarly, now that we know what sticky stuff does to spin, it doesn’t seem so innocent. Like Bauer, Perrin has conducted offseason tests to quantify the effect of sticky stuff on spin, applying various substances—pine tar, Tyrus, Pelican—and then tracking his pitches via a Rapsodo device. He found the typical boost relative to “naked” skin to be about 150 RPM.

Perrin admits that a loss of spin from an absence of sticky stuff would hamper movement and likely lower whiff rates. Another minor league pitcher who’s still active and has reached Triple-A says the same: “If the foreign substances disappeared, my guess would be that there would be a pretty significant decrease in spin rate and whiff rate.”

Deep Throwt concurs, as does former major league pitcher, broadcaster, and author Dirk Hayhurst. “Cutters bite, sliders slide, two-seamers tail with depth,” he says. “Better grip often is the difference between two-plane movement (down and away instead of just away) and single-plane. And tighter, increased rotation generally means late, sharper movement.” The team executive adds that without sticky stuff, “There would be wide-scale reduction in spin rates and ball movement,” and the anonymous major league pitcher who called Bauer’s 70 percent guess conservative admits, “You would definitely see a decrease in strikeouts, increase in walks, increase in offense.” As the pursuit of spin and whiffs has intensified, pitchers have abandoned sinkers in favor of sliders and elevated four-seamers, but if sticky stuff went away, Deep Throwt speculates, “I wouldn’t be surprised if we saw a little bit more shift back to sinkers, just in the fact that if you can’t use a weapon, you’ve got to create a different weapon.”

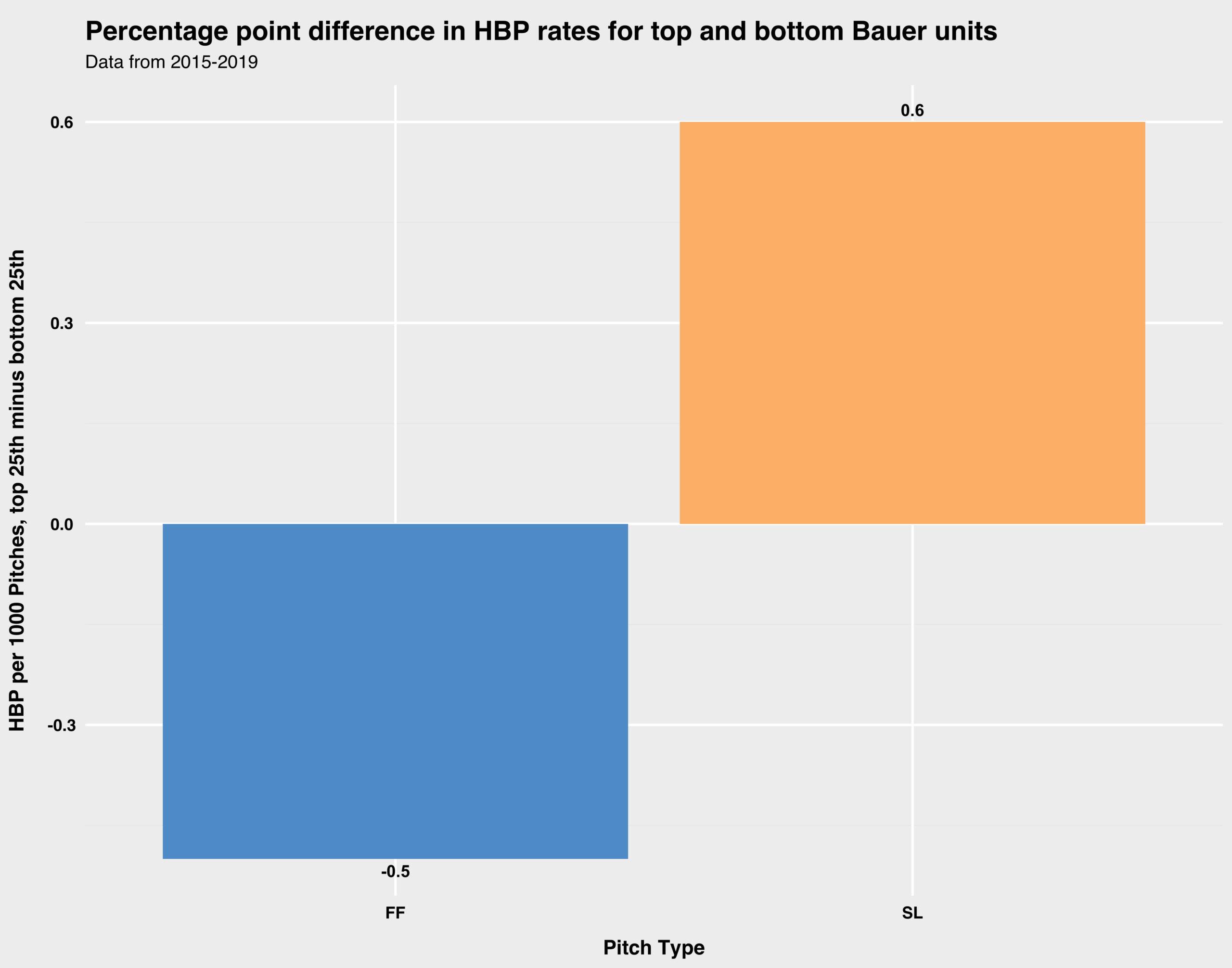

Short of a controlled experiment conducted during major league games, it’s impossible to provide a precise answer for how much eradicating sticky stuff would depress leaguewide whiff rates, but there is one indirect way we can check. Spin rates naturally (or, perhaps, unnaturally) fluctuate somewhat from inning to inning and start to start; as analyst Hareeb al-Saq concluded last year, “Some days pitchers can spin the ball, and sometimes they can’t.” How much more effective are they when they can? If we calculate the difference in whiff rates for each pitcher on his top- and bottom-quartile pitches of each type, based on Bauer units—his 25 percent spinniest pitches and 25 percent slowest-spinning pitches, controlling for speed—then calculate the average difference across all pitchers from 2015-19, controlling for playing time, we get the following chart produced by Petti.

Spin makes a major difference for four-seamers and sliders. Considering that the league-average whiff rates on four-seamers and sliders in that five-season span were 19.9 percent and 35.1 percent, respectively, differences of 3.9 percent and 5.1 percent are sizable. And if anything, that may undersell the true difference between sticky stuff and no sticky stuff: If 70 percent of pitchers or more are using foreign substances at all times, then we’re never really seeing what their stuff would look like plain. If MLB wants to stop the current streak of increasing-strikeout-rate seasons at 14—and restrict the strikeout rise long term—eliminating or severely curtailing the use of the stuff that the rules prohibit pitchers from using might truly work. “I hate the whole thing, ‘Oh, everybody is using it, so make it legal,’” Deep Throwt says. “No, don’t make it legal. It shouldn’t be legal. It’s a performance enhancer.”

It might also interest hitters to learn that in theory, foreign substances could alter the flight of a batted ball. Doctoring the ball, Nathan says, “affects the movement and might affect the drag. If it indeed affects the drag, then the effect on a fly ball (where the flight path is much greater) would be even greater.” Nathan is only speculating; he knows of no studies that have demonstrated this effect, and it’s possible that contact with the bat could dislodge some of the substance on the ball. But tests have shown that minute decreases in seam height reduce drag and increase the carry of fly balls, so it’s not hard to imagine that a load of sticky stuff could obstruct flight and decrease carry. Maybe the juiced ball would be inflating offense even more if its surface were a little less juicy.

One frequent riposte to the argument that sticky stuff should be banished is that the resulting loss of command and control could endanger hitters, placing more heads in harm’s way at a time when hit by pitch rates have already reached historic highs. “I caught a few guys that needed specific combinations of illegal substances to be able to throw strikes,” says a former major league catcher who now works for a team. “There is an element of danger involved in taking away all grip-enhancing substances.” Perrin says plenty of hitters have told him that for safety’s sake, they didn’t care if he used pine tar.

Deep Throwt thinks a few pitchers are wild enough to be hazards without sticky stuff, but he believes that for the vast majority of pitchers at the upper levels, at least, it wouldn’t be a big concern. “If I can make the ball move and know it’s going to move a certain way, it will help me not hit somebody,” he concedes. “At the same time, anybody that’s ever used it to not hit somebody wasn’t that good in the first place to be in the big leagues. Let’s be honest: If I do know where the ball is going better, I’ll have a better chance of not hitting somebody. But come on. I know I’m selling pitchers out, but come on. We’ve never used it for that reason.”

For what it’s worth, if we repeat the above analysis for hit-by-pitch rates instead of whiff rates, we see only minuscule effects: 0.6 more hit by pitches per 1000 sliders, and 0.5 fewer hit by pitches per 1000 four-seamers.

While the prospect of a Thanos snap for sticky stuff makes for a fun thought experiment, the more respectable staples of a pitcher’s sticky craft are too ingrained to go away overnight. Hayhurst says almost every pitcher’s bag contains sunscreen and rosin, shaving cream, and pine tar. “If you’re going to get your hands messy, might as well use what’s already on the mound and on your body, right?” he asks. “It’s easier to cheat—so easy it’s not even considered cheating—with stuff that the umpire has access to. I mean, he sweats, he’s wearing sunscreen, and he put the rosin on the mound.” (The 2020 operations manual mandates that pitchers bring their own rosin bags, and it also specifies that players must “make every effort” to wipe away sweat with their hands and that baseballs be replaced after being put in play and touched by multiple players.)

The simpler and more time-honored the topical substance, the less suspect. MLB seems to be targeting exotic or scientifically tailored mixtures that could cause spin to soar more than omnipresent pine tar, which even many non-pitchers have on their hands from hitting or getting their own grips on the ball. Astros pitching coach Brent Strom told Tom Verducci in March that Young informed the team that “minimal use of a grip aid such as pine tar would continue to be tacitly approved.”

As Hayhurst points out, stripping pitchers of sticky stuff could have psychological side effects in addition to a diminishment in spin. “A hand swollen with blood, armored with callouses, and desensitized by friction isn’t always the best measuring stick,” he says. “However, pitchers do have near ESP levels of ball familiarity. … They would feel different on the mound, which is all it would take for the most sensitive of the bunch to start struggling.”

That’s particularly true because pitchers commonly complain that the balls used in the majors and Triple-A are too slick even after they’re rubbed with mud. “They say those balls are made of leather, but a lot of the times those things are wound so tight that it feels more like you’re throwing a cue ball if you don’t have something to give you a little extra tack,” Perrin says.

According to Verducci and Joel Sherman, MLB and Rawlings are continuing to tinker with prototypes of a baseball with a tacky surface, which would theoretically eliminate the need for grip-enhancing foreign substances. A version of this “consistent grip” ball was tested in an Atlantic League game last year, and at least one hitter complained that it seemed less lively than the regular ball (which might not be a bad thing). Japan’s major leagues have adopted a tacky ball, but Rawlings has spent more than three years searching for a model that would retain its stickiness, behave like the old ball, and not be so bright that it’s overly easy to hit. MLB has also reportedly considered distributing its own sticky substance that would be provided to pitchers and sanctioned in the rule book.

For the time being, though, MLB seems stuck with an uneasy status quo in which the majority of players are likely engaging in a practice that goes against the rules and undeniably enhances performance. MLB has long looked the other way while pitchers got illegal grips, but if we’ve learned anything from the two biggest baseball scandals of this century, it’s that the league’s laissez-faire policies toward certain types of cheating can come back to bite it. PED use and illicit sign stealing were open secrets inside the sport well before they came to Congress’s attention. MLB’s failure to proactively police those practices ultimately weakened the public’s trust in the sport’s competitive integrity, and sticky stuff could conceivably become a similar liability.

Unlike PEDs and sign stealing, the effects of which are challenging to isolate and often overstated, the use of foreign substances produces demonstrable and significant gains, potentially on every pitch. And while PEDs and illicit sign stealing theoretically lead to increases in crowd-pleasing contact and runs, sticky stuff acts like a wet rag blanket, suppressing scoring and balls in play. Almost paradoxically, the antidote to sticky substances may be a stickier ball: “Unless they actually change the ball, I don’t see a fix for this,” the anonymous major leaguer says. As is often the case, one of the sport’s problems, and a possible solution, lead back to the ball itself—a sphere that’s looked largely the same for a century but keeps flying farther and spinning faster than it ever has before.